사용자:배우는사람/틀:지역 둘러보기/문서:유럽

Europe[편집]

한영병기판[편집]

틀:Other uses 틀:Pp-semi-indef틀:Pp-move-indef 틀:Infobox Continent

Europe (/ˈjʊərəp/ YEWR-əp or /ˈjɜrəp/ YUR-əp[1]) is one of the world's seven 대륙(continent)s. Comprising the westernmost peninsula(peninsula) of 유라시아(Eurasia), Europe is generally divided from 아시아(Asia) to its east by the water divide(water divide) of the 우랄 산맥(Ural Mountains), the 우랄 강]](Ural River), the 카스피 해(Caspian Sea), the 캅카스(Caucasus) region (Specification of borders]](Specification of borders)) and the 흑해(Black Sea) to the southeast.[2] Europe is bordered by the 북극해(Arctic Ocean) and other bodies of water to the north, the 대서양(Atlantic Ocean) to the west, the 지중해(Mediterranean Sea) to the south, and the 흑해(Black Sea) and connected waterways to the southeast. Yet the borders for Europe—a concept dating back to 고전 고대(classical antiquity)—are somewhat arbitrary, as the term continent can refer to a cultural and political]](cultural and political) distinction or a physiographic]](physiographic) one.

Europe is the world's second-smallest]](second-smallest) continent by surface area, covering about 10,180,000 square kilometres (3,930,000 sq mi) or 2% of the Earth's surface and about 6.8% of its land area. Of Europe's approximately 50 states, 러시아(Russia) is the largest by both area and population (although the country covers both Europe and Asia), while the 바티칸 시국(Vatican City) is the smallest. Europe is the third-most populous continent after 아시아(Asia) and 아프리카(Africa), with a 인구]](population) of 731 million or about 11% of the 세계 인구(world's population).

Europe, in particular 고대 그리스(Ancient Greece), is the birthplace of Western culture(Western culture).[3] It played a predominant role in global affairs from the 16th century onwards, especially after the beginning of 식민주의(colonialism). Between the 16th and 20th centuries, European nations controlled at various times the Americas]](the Americas), most of Africa]](most of Africa), 오세아니아(Oceania), and large portions of Asia. Both World War(World War)s were largely focused upon Europe, greatly contributing to a decline in 서유럽(Western Europe)an dominance in world affairs by the mid-20th century as the 미국(United States) and 소비에트 연방(Soviet Union) took prominence.[4] During the 냉전(Cold War), Europe was divided along the 철의 장막(Iron Curtain) between 북대서양 조약 기구(NATO) in the west and the 바르샤바 조약 기구(Warsaw Pact) in the east. 유럽 통합(European integration) led to the formation of the 유럽 평의회(Council of Europe) and the 유럽 연합(European Union) in 서유럽(Western Europe), both of which have been expanding eastward since the fall of the Soviet Union]](fall of the Soviet Union) in 1991.

Definition[편집]

The use of the term "Europe" has developed gradually throughout history.[5][6] In antiquity, the Greek historian 헤로도토스(Herodotus) mentioned that the world had been divided by unknown persons into the three 대륙(continent)s of Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa), with the 나일 강(Nile) and the river Phasis]](river Phasis) forming their boundaries—though he also states that some considered the 돈 강(River Don), rather than the Phasis, as the boundary between Europe and Asia.[7] Flavius Josephus(Flavius Josephus) and the Book of Jubilees(Book of Jubilees) described the continents as the lands given by 노아(Noah) to his three sons; Europe was defined as between the 헤라클레스의 기둥(Pillars of Hercules) at the 지브롤터 해협(Strait of Gibraltar), separating it from Africa, and the 돈 강(Don), separating it from Asia.[8]

A cultural definition of Europe as the lands of Latin Christendom]](Latin Christendom) coalesced in the 8th century, signifying the new cultural condominium created through the confluence of Germanic traditions and Christian-Latin culture, defined partly in contrast with 비잔티움(Byzantium) and 이슬람교(Islam), and limited to northern Iberia, the British Isles, France, Christianized western Germany, the Alpine regions and northern and central Italy.[9] The concept is one of the lasting legacies of the Carolingian Renaissance(Carolingian Renaissance): "Europa" often figures in the letters of Charlemagne's cultural minister, Alcuin(Alcuin).[10] This division—as much cultural as geographical—was used until the Late Middle Ages(Late Middle Ages), when it was challenged by the 대항해 시대(Age of Discovery).[11][12] The problem of redefining Europe was finally resolved in 1730 when, instead of waterways, the Swedish geographer and cartographer von Strahlenberg]](von Strahlenberg) proposed the 우랄 산맥(Ural Mountains) as the most significant eastern boundary, a suggestion that found favour in 러시아(Russia) and throughout Europe.[13]

Europe is now generally defined by geographers as the westernmost peninsula(peninsula) of Eurasia, with its boundaries marked by large bodies of water to the north, west and south; Europe's limits to the far east are usually taken to be the Urals, the 우랄 강]](Ural River), and the 카스피 해(Caspian Sea); to the south-east, the 캅카스 산맥(Caucasus Mountains), the 흑해(Black Sea) and the waterways connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.[14]

Sometimes, the word 'Europe' is used in a geopolitically limiting way[15] to refer only to the European Union or, even more exclusively, a culturally defined core. On the other hand, the 유럽 평의회(Council of Europe) has 47 member countries, and only 27 member states are in the EU.[16] In addition, people living in insular areas such as 아일랜드 섬(Ireland), the 영국(United Kingdom), the North Atlantic(North Atlantic) and Mediterranean(Mediterranean) islands and also in 스칸디나비아(Scandinavia) may routinely refer to "continental" or "mainland" Europe]]("continental" or "mainland" Europe) simply as Europe or "the Continent".[17]

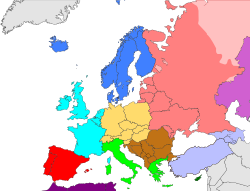

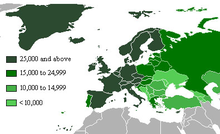

Clickable map of Europe, showing one of the most commonly used geographical boundaries[18] (legend: blue = 두 대륙에 걸친 나라#아 시아와 유럽에 걸친 나라(states in both Europe and Asia); green = sometimes included within Europe but geographically outside Europe's boundaries) 틀:Europe and Sea

Etymology[편집]

In ancient 그리스 신화(Greek mythology), 에우로파(Europa) was a 페니키아(Phoenicia)n princess whom 제우스(Zeus) abducted after assuming the form of a dazzling white bull. He took her to the island of 크레타(Crete) where she gave birth to 미노스(Minos), 라다만티스(Rhadamanthus) and 사르페돈(Sarpedon). For 호메로스(Homer), Europe (그리스어(Greek): Εὐρώπη, Eurṓpē; see also List of traditional Greek place names(List of traditional Greek place names)) was a mythological queen of Crete, not a geographical designation. Later, Europa stood for central-north Greece]](central-north Greece), and by 500 BC its meaning had been extended to the lands to the north.

The name of Europa is of uncertain etymology.[19] One theory suggests that it is derived from the 그리스어(Greek roots) meaning broad (eur-) and eye (op-, opt-), hence Eurṓpē, "wide-gazing", "broad of aspect" (compare with glaukōpis (grey-eyed) Athena]](glaukōpis (grey-eyed) Athena) or boōpis (ox-eyed) Hera]](boōpis (ox-eyed) Hera)). Broad has been an epithet(epithet) of 지구(Earth) itself in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion(Proto-Indo-European religion).[20] Another theory suggests that it is actually based on a 셈족(Semitic) word such as the Akkadian]](Akkadian) erebu meaning "to go down, set" (cf. Occident(Occident)),[21] 동계어(cognate) to Phoenician 'ereb "evening; west" and Arabic 마그레브(Maghreb), Hebrew ma'ariv (see also 에레보스(Erebus), PIE]](PIE) *h1regʷos, "darkness"). However, M. L. West states that "phonologically, the match between Europa's name and any form of the Semitic word is very poor".[22]

Most major world languages use words derived from "Europa" to refer to the "continent" (peninsula). Chinese, for example, uses the word Ōuzhōu (歐洲), which is an abbreviation of the transliterated name Ōuluóbā zhōu (歐羅巴洲); however, in some Turkic languages the name Frengistan (land of the 프랑크족(Franks)) is used casually in referring to much of Europe, besides official names such as Avrupa or Evropa.[23]

History[편집]

Prehistory[편집]

(The Lady of Vinča), neolithic pottery from 세르비아(Serbia)]]

호모 게오르기쿠스(Homo georgicus), which lived roughly 1.8 million years ago in 조지아(Georgia), is the earliest hominid(hominid) to have been discovered in Europe.[24] Other hominid remains, dating back roughly 1 million years, have been discovered in Atapuerca(Atapuerca), 스페인(Spain).[25] Neanderthal man(Neanderthal man) (named for the Neander Valley(Neander Valley) in 독일(Germany)) appeared in Europe 150,000 years ago and disappeared from the fossil record about 30,000 years ago. The Neanderthals were supplanted by modern humans (Cro-Magnons(Cro-Magnons)), who appeared in Europe around 40,000 years ago.[26]

The European Neolithic(European Neolithic) period—marked by the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock, increased numbers of settlements and the widespread use of pottery—began around 7,000 BC in 그리스(Greece) and the 발칸 반도(Balkans), probably influenced by earlier farming practices in 아나톨리아(Anatolia) and the 근동(Near East). It spread from South Eastern Europe along the valleys of the 도나우 강(Danube) and the 라인 강(Rhine) (Linear Pottery culture(Linear Pottery culture)) and along the Mediterranean coast(Mediterranean coast) (Cardial culture]](Cardial culture)). Between 4,500 and 3,000 BC these central European neolithic cultures developed further to the west and the north, transmitting newly acquired skills in producing copper artefacts. In Western Europe the Neolithic period was characterised not by large agricultural settlements but by field monuments, such as causewayed enclosure(causewayed enclosure)s, burial mound(burial mound)s and megalithic tomb(megalithic tomb)s.[27] The Corded ware(Corded ware) cultural horizon flourished at the transition from the Neolithic to the 동기 시대(Chalcolithic). During this period giant megalithic(megalithic) monuments, such as the Megalithic Temples of Malta(Megalithic Temples of Malta) and 스톤헨지(Stonehenge), were constructed throughout Western and Southern Europe.[28][29] The European Bronze Age(European Bronze Age) began in the late 3rd millennium BC with the Beaker culture(Beaker culture).

The European Iron Age(European Iron Age) began around 800 BC, with the Hallstatt culture(Hallstatt culture). Iron Age colonisation by the Phoenicians(Phoenicians) gave rise to early Mediterranean]](Mediterranean) cities. Early Iron Age Italy(Iron Age Italy) and 그리스(Greece) from around the 8th century BC gradually gave rise to historical 고전 고대(Classical Antiquity).

Classical antiquity[편집]

고대 그리스(Ancient Greece) had a profound impact on Western civilisation. Western democratic]](democratic) and individualistic culture]](individualistic culture) are often attributed to Ancient Greece.[30] The Greeks invented the 폴리스(polis), or city-state, which played a fundamental role in their concept of identity.[31] These Greek political ideals were rediscovered in the late 18th century by European philosophers and idealists. Greece also generated many cultural contributions: in 철학(philosophy), 인문주의(humanism) and 합리주의(rationalism) under 아리스토텔레스(Aristotle), 소크라테스(Socrates) and 플라톤(Plato); in 역사]](history) with 헤로도토스(Herodotus) and 투키디데스(Thucydides); in dramatic and narrative verse, starting with the epic poems of 호메로스(Homer);[30] and in science with 피타고라스(Pythagoras), 에우클레이데스(Euclid) and 아르키메데스(Archimedes).[32][33][34]

Another major influence on Europe came from the 로마 제국(Roman Empire) which left its mark on 법(law), 언어(language), 공학]](engineering), 건축]](architecture), and 정부]](government).[35] During the pax romana(pax romana), the Roman Empire expanded to encompass the entire Mediterranean Basin(Mediterranean Basin) and much of Europe.[36]

스토아 학파(Stoicism) influenced Roman emperor(Roman emperor)s such as 하드리아누스(Hadrian), 안토니누스 피우스(Antoninus Pius), and 마르쿠스 아우렐리우스(Marcus Aurelius), who all spent time on the Empire's northern border fighting Germanic]](Germanic), Pictish]](Pictish) and Scottish]](Scottish) tribes.[37][38] 기독교(Christianity) was eventually legitimised]](legitimised) by 콘스탄티누스 1세(Constantine I) after three centuries of imperial persecution]](imperial persecution).

Early Middle Ages[편집]

During the decline of the Roman Empire(decline of the Roman Empire), Europe entered a long period of change arising from what historians call the "Age of Migrations(Age of Migrations)". There were numerous invasions and migrations amongst the 동고트 왕국(Ostrogoths), 서고트족(Visigoths), 고트족(Goths), 반달족(Vandals), 훈족(Huns), 프랑크족(Franks), 앵글족(Angles), 색슨족(Saxons), Slavs(Slavs), Avars]](Avars), 불가르족(Bulgars) and, later still, the Vikings(Vikings) and Magyars(Magyars).[36] 르네상스(Renaissance) thinkers such as 프란체스코 페트라르카(Petrarch) would later refer to this as the "Dark Ages(Dark Ages)".[39] Isolated monastic communities were the only places to safeguard and compile written knowledge accumulated previously; apart from this very few written records survive and much literature, philosophy, mathematics, and other thinking from the classical period disappeared from Europe.[40]

During the Dark Ages, the 서로마 제국(Western Roman Empire) fell under the control of various tribes. The Germanic and Slav tribes established their domains over Western and Eastern Europe respectively.[41] Eventually the 프랑크족(Frankish tribes) were united under [[Clovis I]]([[:en:Clovis I|Clovis I]]).[42] 카롤루스 대제(Charlemagne), a Frankish king of the Carolingian(Carolingian) dynasty who had conquered most of Western Europe, was anointed "신성 로마 제국의 황제(Holy Roman Emperor)" by the Pope in 800. This led to the founding of the 신성 로마 제국(Holy Roman Empire), which eventually became centred in the German principalities of central Europe.[43]

The predominantly Greek speaking]](Greek speaking) Eastern Roman Empire(Eastern Roman Empire) became known in the west as the 비잔티움 제국(Byzantine Empire). Its capital was 콘스탄티노폴리스(Constantinople). Emperor 유스티니아누스 1세(Justinian I) presided over Constantinople's first golden age: he established a legal code]](legal code), funded the construction of the 아야 소피아(Hagia Sophia) and brought the Christian church under state control.[44] Fatally weakened by the sack of Constantinople during the 제4차 십자군(Fourth Crusade), the Byzantines fell in 1453 when they were conquered by the 오스만 제국(Ottoman Empire).[45]

Middle Ages[편집]

(Philip II), during the 제3차 십자군(Third Crusade)]]

The 중세(Middle Ages) were dominated by the two upper echelons of the social structure: the nobility and the clergy. 봉건 제도(Feudalism) developed in 프랑스(France) in the Early Middle Ages(Early Middle Ages) and soon spread throughout Europe.[46] A struggle for influence between the 귀족(nobility) and the 군주제(monarchy) in England led to the writing of the 마그나 카르타(Magna Carta) and the establishment of a 의회(parliament).[47] The primary source of culture in this period came from the Roman Catholic Church(Roman Catholic Church). Through monasteries and cathedral schools, the Church was responsible for education in much of Europe.[46]

The Papacy(Papacy) reached the height of its power during the High Middle Ages. A East-West Schism(East-West Schism) in 1054 split the former Roman Empire religiously, with the 동방 정교회(Eastern Orthodox Church) in the 비잔티움 제국(Byzantine Empire) and the Roman Catholic Church(Roman Catholic Church) in the former Western Roman Empire. In 1095 교황 우르바노 2세(Pope Urban II) called for a crusade]](crusade) against Muslims(Muslims) occupying 예루살렘(Jerusalem) and the 성지(Holy Land).[48] In Europe itself, the Church organised the 종교 재판(Inquisition) against heretics. In 스페인(Spain), the 레콘키스타(Reconquista) concluded with the fall of 그라나다 (스페인)(Granada) in 1492, ending over seven centuries of Muslim rule in the 이베리아 반도(Iberian Peninsula).[49]

(Chronicles); the battle established England as a military power.]]

In the 11th and 12th centuries, constant incursions by nomadic Turkic]](Turkic) tribes, such as the 페체네그족(Pechenegs) and the Kipchaks(Kipchaks), caused a massive migration of Slavic]](Slavic) populations to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north.[50] Like many other parts of 유라시아(Eurasia), these territories were overrun by the Mongols]](overrun by the Mongols).[51] The invaders, later known as 타타르족(Tatars), formed the state of the 킵차크 칸국(Golden Horde), which ruled the southern and central expanses of Russia for over three centuries.[52]

The Great Famine of 1315–1317(Great Famine of 1315–1317) was the first crisis]](crisis) that would strike Europe in the late Middle Ages.[53] The period between 1348 and 1420 witnessed the heaviest loss. The population of 프랑스(France) was reduced by half.[54][55] Medieval Britain was afflicted by 95 famines,[56] and France suffered the effects of 75 or more in the same period.[57] Europe was devastated in the mid-14th century by the 흑사병(Black Death), one of the most deadly 범유행(pandemic)s in human history which killed an estimated 25 million people in Europe alone—a third of the European population]](European population) at the time.[58]

The plague had a devastating effect on Europe's social structure; it induced people to live for the moment as illustrated by 조반니 보카치오(Giovanni Boccaccio) in 데카메론(The Decameron) (1353). It was a serious blow to the Roman Catholic Church(Roman Catholic Church) and led to increased persecution of Jews(persecution of Jews), foreigners, beggars(beggars) and leper(leper)s.[59] The plague is thought to have returned every generation with varying virulence(virulence) and mortalities until the 18th century.[60] During this period, more than 100 plague epidemics]](epidemics) swept across Europe.[61]

Early modern period[편집]

(The School of Athens) by 라파엘로(Raphael): Contemporaries such as 미켈란젤로 부오나로티(Michelangelo) and 레오나르도 다 빈치(Leonardo da Vinci) (centre) are portrayed as classical scholars]]

The 르네상스(Renaissance) was a period of cultural change originating in 피렌체(Florence) and later spreading to the rest of Europe. in the 14th century. The rise of a new humanism]](new humanism) was accompanied by the recovery of forgotten classical and Arabic knowledge from monastic libraries and the Islamic world.[62][63][64] The Renaissance spread across Europe between the 14th and 16th centuries: it saw the flowering of art, philosophy, music, and the sciences, under the joint patronage of royalty, the nobility, the Roman Catholic Church, and an emerging merchant class.[65][66][67] Patrons in Italy, including the Medici(Medici) family of 피렌체(Florentine) bankers and the 교황(Pope)s in 로마(Rome), funded prolific quattrocento(quattrocento) and cinquecento(cinquecento) artists such as 라파엘로(Raphael), 미켈란젤로 부오나로티(Michelangelo), and 레오나르도 다 빈치(Leonardo da Vinci).[68][69]

Political intrigue within the Church in the mid-14th century caused the Great Schism]](Great Schism). During this forty-year period, two popes—one in 아비뇽(Avignon) and one in 로마(Rome)—claimed rulership over the Church. Although the schism was eventually healed in 1417, the papacy's spiritual authority had suffered greatly.[70]

The Church's power was further weakened by the 종교 개혁(Protestant Reformation) (1517–1648), initially sparked by the works of]](by the works of) German theologian 마르틴 루터(Martin Luther), a result of the lack of reform within the Church. The Reformation also damaged the Holy Roman Empire's power, as German princes became divided between Protestant(Protestant) and Roman Catholic faiths.[71] This eventually led to the Thirty Years War(Thirty Years War) (1618–1648), which crippled the Holy Roman Empire and devastated much of 독일]](Germany), killing between 25 and 40 percent of its population.[72] In the aftermath of the 베스트팔렌 조약(Peace of Westphalia), 프랑스(France) rose to predominance within Europe.[73] The 17th century in southern and eastern Europe was a period of general decline.[74] Eastern Europe experienced more than 150 famines in a 200-year period between 1501 to 1700.[75]

The Renaissance and the New Monarchs(New Monarchs) marked the start of an 대항해 시대(Age of Discovery), a period of exploration, invention, and scientific development. In the 15th century, 포르투갈(Portugal) and 스페인(Spain), two of the greatest naval powers of the time, took the lead in exploring the world.[76][77] 크리스토퍼 콜럼버스(Christopher Columbus) reached the 신세계(New World) in 1492, and soon after the Spanish and Portuguese began establishing colonial empires in the Americas.[78] 프랑스(France), the 네덜란드(Netherlands) and 잉글랜드(England) soon followed in building large colonial empires with vast holdings in Africa, the Americas(the Americas), and Asia.

18th and 19th centuries[편집]

The 계몽주의(Age of Enlightenment) was a powerful intellectual movement during the 18th century promoting scientific and reason-based thoughts.[79][80][81] Discontent with the aristocracy and clergy's monopoly on political power in France resulted in the 프랑스 혁명(French Revolution) and the establishment of the 제1공화국 (동음이의)(First Republic) as a result of which the monarchy and many of the nobility perished during the initial reign of terror(reign of terror).[82] Napoleon Bonaparte]](Napoleon Bonaparte) rose to power in the aftermath of the French Revolution and established the 프랑스 제1제국(First French Empire) that, during the 나폴레옹 전쟁(Napoleonic Wars), grew to encompass large parts of Europe before collapsing in 1815 with the 워털루 전투(Battle of Waterloo).[83][84]

Napoleonic rule]](Napoleonic rule) resulted in the further dissemination of the ideals of the French Revolution, including that of the nation-state(nation-state), as well as the widespread adoption of the French models of administration]](administration), 법]](law), and 교육(education).[85][86][87] The 빈 회의(Congress of Vienna), convened after Napoleon's downfall, established a new balance of power]](balance of power) in Europe centred on the five "Great Power(Great Power)s": the 영국(United Kingdom), 프랑스(France), 프로이센(Prussia), Habsburg Austria]](Habsburg Austria), and Russia.[88]

This balance would remain in place until the 1848년 혁명(Revolutions of 1848), during which liberal uprisings affected all of Europe except for Russia and Great Britain. These revolutions were eventually put down by conservative elements and few reforms resulted.[89] In 1867, the Austro-Hungarian empire(Austro-Hungarian empire) was formed]](formed); and 1871 saw the unifications of both 이탈리아(Italy) and 독일(Germany) as nation-states(nation-states) from smaller principalities.[90]

The 산업 혁명(Industrial Revolution) started in 그레이트브리튼 섬(Great Britain) in the last part of the 18th century and spread throughout Europe. The invention and implementation of new technologies resulted in rapid urban growth, mass employment, and the rise of a new working class.[91] Reforms in social and economic spheres followed, including the first laws]](first laws) on 아동 노동(child labour), the legalisation of trade union(trade union)s,[92] and the abolition of slavery(abolition of slavery).[93] In 브리튼(Britain), the Public Health Act 1875(Public Health Act 1875) was passed, which significantly improved living conditions in many British cities.[94] Europe’s population]](Europe’s population) doubled during the 18th century, from roughly 100 million to almost 200 million, and doubled again during the 19th century.[95] In the 19th century, 70 million people left Europe in migrations to various European colonies abroad and to the 미국(United States).[96]

20th century to present[편집]

(Entente powers) grey and neutral countries yellow]]

Two World Wars and an economic depression dominated the first half of the 20th century. 제1차 세계 대전(World War I) was fought between 1914 and 1918. It started when 프란츠 페르디난트 대공(Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria) was assassinated by the Bosnian Serb]](Bosnian Serb) 가브릴로 프린치프(Gavrilo Princip).[97] Most European nations were drawn into the war, which was fought between the Entente Powers(Entente Powers) (프랑스(France), 벨기에(Belgium), 세르비아(Serbia), 포르투갈(Portugal), 러시아(Russia), the 영국(United Kingdom), and later 이탈리아(Italy), 그리스(Greece), 루마니아(Romania), and the 미국(United States)) and the 동맹국(Central Powers) (오스트리아-헝가리 제국(Austria-Hungary), 독일(Germany), 불가리아(Bulgaria), and the 오스만 제국(Ottoman Empire)). The War left around 40 million civilians and military dead.[98] Over 60 million European soldiers were mobilised from 1914–1918.[99]

Partly as a result of its defeat Russia was plunged into the Russian Revolution]](Russian Revolution), which threw down the 러시아 제국(Tsarist monarchy) and replaced it with the communist(communist) 소비에트 연방(Soviet Union).[100] 오스트리아-헝가리 제국(Austria-Hungary) and the 오스만 제국(Ottoman Empire) collapsed and broke up into separate nations, and many other nations had their borders redrawn. The 베르사유 조약(Treaty of Versailles), which officially ended 제1차 세계 대전(World War I) in 1919, was harsh towards 독일(Germany), upon whom it placed full responsibility for the war and imposed heavy sanctions.[101]

Economic instability, caused in part by debts incurred in the First World War and 'loans' to Germany played havoc in Europe in the late 1920s and 1930s. This and the 검은 목요일(Wall Street Crash of 1929) brought about the worldwide 대공황(Great Depression). Helped by the economic crisis, social instability and the threat of communism, fascist movements]](fascist movements) developed throughout Europe placing 아돌프 히틀러(Adolf Hitler) of 나치 독일(Nazi Germany), 프란시스코 프랑코(Francisco Franco) of 스페인(Spain) and 베니토 무솔리니(Benito Mussolini) of 이탈리아(Italy) in power.[102][103]

In 1933, Hitler became the leader of Germany and began to work towards his goal of building Greater Germany. Germany re-expanded and took back the 자를란트 주(Saarland) and 라인란트(Rhineland) in 1935 and 1936. In 1938, 오스트리아(Austria) became a part of Germany too, following the 오스트리아 병합(Anschluss). Later that year, Germany annexed the German 수데텐란트(Sudetenland), which had become a part of 체코슬로바키아(Czechoslovakia) after the war. This move was highly contested by the other powers, but ultimately permitted in the hopes of avoiding war and appeasing]](appeasing) Hitler.

Shortly afterwards, Poland and Hungary started to press for the annexation of parts of Czechoslovakia with Polish and Hungarian majorities. Hitler encouraged the Slovaks to do the same and in early 1939, the remainder of Czechoslovakia was split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia(Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia), controlled by Germany, and the Slovak Republic]](Slovak Republic), while other smaller regions went to Poland and Hungary. With tensions mounting between Germany and Poland over the future of Danzig(Danzig), the Germans turned to the Soviets, and signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact(Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). Germany invaded Poland]](invaded Poland) on 1 September 1939, prompting France and the United Kingdom to declare war on Germany on 3 September, opening the European theatre]](European theatre) of 제2차 세계 대전(World War II).[104][105] The Soviet invasion of Poland(Soviet invasion of Poland) started on 17 September and Poland fell soon thereafter.

(Big Three)" at the 얄타 회담(Yalta Conference) in 1945; seated (from the left): 윈스턴 처칠(Winston Churchill), 프랭클린 D. 루스벨트(Franklin D. Roosevelt), and 이오시프 스탈린(Joseph Stalin)]]

On 24 September, the Soviet Union attacked the Baltic countries]](Baltic countries) and later, Finland. The British hoped to land at Narvik and send troops to aid Finland, but their primary objective in the landing was to encircle Germany and cut the Germans off from Scandinavian resources. Nevertheless, the Germans knew of Britain's plans and got to Narvik first, repulsing the attack. Around the same time, Germany moved troops into Denmark, which left no room for a front except for where the last war had been fought or by landing at sea. The 가짜 전쟁(Phoney War) continued.

In May 1940, Germany attacked France through the Low Countries. France capitulated in June 1940. However, the British refused to negotiate peace terms with the Germans and the war continued. By August Germany began a bombing offensive on Britain]](bombing offensive on Britain), but failed to convince the Britons to give up.[106] In 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in the ultimately unsuccessful 바르바로사 작전(Operation Barbarossa).[107] On 7 December 1941 Japan's]](Japan's) 진주만 공격(attack on Pearl Harbor) drew the United States into the conflict as allies of the 대영 제국(British Empire) and other 연합국 (제2차 세계 대전)(allied) forces.[108][109]

After the staggering 스탈린그라드 전투(Battle of Stalingrad) in 1943, the German offensive in the Soviet Union turned into a continual fallback. In 1944, British and American forces invaded France in the D-Day]](D-Day) landings, opening a new front against Germany. 베를린(Berlin) finally fell in 1945, ending World War II in Europe.

The war was the largest and most destructive in human history, with 60 million dead across the world]](60 million dead across the world).[110] More than 40 million people in Europe had lost their lives by the time World War II ended,[111] including between 11 and 17 million people who perished during 홀로코스트(the Holocaust).[112] The 소비에트 연방(Soviet Union) lost around 27 million people during the war, about half of all World War II casualties.[113] By the end of World War II, Europe had more than 40 million 난민(refugee)s.[114] Several post-war expulsions]](post-war expulsions) in Central and Eastern Europe displaced a total of about 20 million people.[115]

(9 May) 1950) lead to the creation of the 유럽 석탄 철강 공동체(European Coal and Steel Community). It began the 유럽 통합(integration process) which today comprises the 유럽 연합(European Union) of 27 democratic countries in Europe]]

World War I and especially World War II diminished the eminence of Western Europe in world affairs. After World War II the map of Europe was redrawn at the 얄타 회담(Yalta Conference) and divided into two blocs, the Western countries and the communist(communist) Eastern bloc, separated by what was later called by 윈스턴 처칠(Winston Churchill) an "철의 장막(iron curtain)". The United States and Western Europe established the 북대서양 조약 기구(NATO) alliance and later the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe established the 바르샤바 조약 기구(Warsaw Pact).[116]

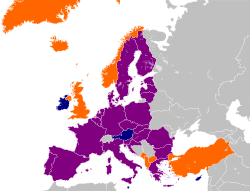

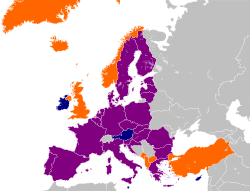

The two new 초강대국(superpower)s, the 미국(United States) and the 소비에트 연방(Soviet Union), became locked in a fifty-year long 냉전(Cold War), centred on 핵확산(nuclear proliferation). At the same time decolonisation(decolonisation), which had already started after World War I, gradually resulted in the independence of most of the European colonies in Asia and Africa.[4] In the 1980s the reforms]](reforms) of 미하일 고르바초프(Mikhail Gorbachev) and the 연대 (사회학)(Solidarity) movement in Poland accelerated the collapse of the Eastern bloc and the end of the Cold War. Germany was reunited, after the symbolic fall of the Berlin Wall(fall of the Berlin Wall) in 1989, and the maps of Eastern Europe were redrawn once more.[117] 유럽 통합(European integration) also grew in the post-World War II years. The Treaty of Rome(Treaty of Rome) in 1957 established the 유럽 경제 공동체(European Economic Community) between six Western European states with the goal of a unified economic policy and common market.[118] In 1967 the EEC, 유럽 석탄 철강 공동체(European Coal and Steel Community) and Euratom(Euratom) formed the European Community(European Community), which in 1993 became the 유럽 연합(European Union). The EU established a 의회(parliament), 법원(court) and 중앙은행(central bank) and introduced the 유로(euro) as a unified currency.[119] In 2004 and 2007, Eastern European countries began joining, expanding the EU]](expanding the EU) to its current size of 27 European countries, and once more making Europe a major economical and political centre of power.[120]

Geography and extent[편집]

자연지리학(Physiographically), Europe is the northwestern constituent of the larger landmass known as 유라시아(Eurasia), or 아프로·유라시아(Afro-Eurasia): Asia occupies the eastern bulk of this continuous landmass and all share a common 대륙붕(continental shelf). Europe's eastern frontier is now commonly delineated by the 우랄 산맥(Ural Mountains) in Russia.[14]

The first border definition was introduced in 5th Century B.C. by the "father of history" 헤로도토스(Herodotus), when he regarded Europe to be extending to the 태평양(Eastern Ocean), and being as long as (and much larger than) Africa and Asia together. He marked the borders between Europe and Asia on 쿠라 강(Kura River) and 리오니 강(Rioni River) in Transcaucasia(Transcaucasia).[121] The 1st century AD geographer 스트라본(Strabo), took the 돈 강(River Don) "Tanais" to be the boundary to the 흑해(Black Sea),[122] as did early Judaic]](Judaic) sources.[출처 필요]

The southeast boundary with Asia is not universally defined, with the 우랄 강(Ural River), or alternatively, the 엠바 강(Emba River) most commonly serving as possible boundaries. The boundary continues to the 카스피 해(Caspian Sea), the crest of the 캅카스 산맥(Caucasus Mountains) or, alternatively, the 쿠라 강(Kura River) in the 캅카스(Caucasus), and on to the 흑해(Black Sea); the Bosporus(Bosporus), the 마르마라 해(Sea of Marmara), the 다르다넬스 해협(Dardanelles), and the 에게 해(Aegean Sea) conclude the Asian boundary. The 지중해(Mediterranean Sea) to the south separates Europe from Africa. The western boundary is the Atlantic Ocean; 아이슬란드(Iceland), though nearer to 그린란드(Greenland) (North America) than mainland Europe, is generally included in Europe.

Because of sociopolitical and cultural differences, there are various descriptions of Europe's boundary; in some sources, some territories are not included in Europe, while other sources include them. For instance, geographers from Russia and other post-Soviet states]](Russia and other post-Soviet states) generally include the Urals in Europe while including Caucasia in Asia. Similarly, 키프로스(Cyprus) is approximate to 아나톨리아(Anatolia (or Asia Minor)), but is often considered part of Europe and currently is a member state of the EU. In addition, Malta was considered an island of Africa for centuries.[123]

Physical geography[편집]

Land relief in Europe shows great variation within relatively small areas. The southern regions are more mountainous, while moving north the terrain descends from the high 알프스 산맥(Alps), 피레네 산맥(Pyrenees) and 카르파티아 산맥(Carpathians), through hilly uplands, into broad, low northern plains, which are vast in the east. This extended lowland is known as the Great European Plain(Great European Plain), and at its heart lies the North German Plain(North German Plain). An arc of uplands also exists along the north-western seaboard, which begins in the western parts of the islands of 브리튼(Britain) and Ireland, and then continues along the mountainous, 피오르(fjord)-cut, spine of Norway.

This description is simplified. Sub-regions such as the 이베리아 반도(Iberian Peninsula) and the 이탈리아 반도(Italian Peninsula) contain their own complex features, as does mainland Central Europe itself, where the relief contains many plateaus, river valleys and basins that complicate the general trend. Sub-regions like 아이슬란드(Iceland), Britain and Ireland are special cases. The former is a land unto itself in the northern ocean which is counted as part of Europe, while the latter are upland areas that were once joined to the mainland until rising sea levels cut them off.

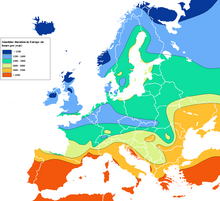

Climate[편집]

툰드라(tundra) alpine tundra(alpine tundra) 타이가(taiga) montane forest(montane forest)

temperate broadleaf forest(temperate broadleaf forest) mediterranean forest(mediterranean forest) temperate steppe(temperate steppe) dry steppe(dry steppe)

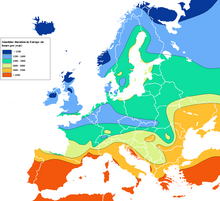

Europe lies mainly in the temperate(temperate) climate zones, being subjected to prevailing westerlies(prevailing westerlies).

The climate is milder in comparison to other areas of the same latitude around the globe due to the influence of the 멕시코 만류(Gulf Stream).[124] The Gulf Stream is nicknamed "Europe's central heating", because it makes Europe's climate warmer and wetter than it would otherwise be. The Gulf Stream not only carries warm water to Europe's coast but also warms up the prevailing westerly winds that blow across the continent from the Atlantic Ocean.

Therefore the average temperature throughout the year of Naples is 16 °C (60.8 °F), while it is only 12 °C (53.6 °F) in New York City which is almost on the same latitude. Berlin, Germany; Calgary, Canada; and Irkutsk, in the Asian part of Russia, lie on around the same latitude; January temperatures in Berlin average around 8 °C (15 °F) higher than those in Calgary, and they are almost 22 °C (40 °F) higher than average temperatures in Irkutsk.[124]

Geology[편집]

The Geology of Europe is hugely varied and complex, and gives rise to the wide variety of landscapes found across the continent, from the Scottish Highlands(Scottish Highlands) to the rolling 평야(plain)s of Hungary.[125]

Europe's most significant feature is the dichotomy between highland and mountainous 남유럽(Southern Europe) and a vast, partially underwater, northern plain ranging from Ireland in the west to the 우랄 산맥(Ural Mountains) in the east. These two halves are separated by the mountain chains of the 피레네 산맥(Pyrenees) and 알프스 산맥(Alps)/카르파티아 산맥(Carpathians). The northern plains are delimited in the west by the 스칸디나비아 산맥(Scandinavian Mountains) and the mountainous parts of the British Isles. Major shallow water bodies submerging parts of the northern plains are the 켈트 해(Celtic Sea), the 북해(North Sea), the 발트 해(Baltic Sea) complex and 바렌츠 해(Barents Sea).

The northern plain contains the old geological continent of Baltica(Baltica), and so may be regarded geologically as the "main continent", while peripheral highlands and mountainous regions in the south and west constitute fragments from various other geological continents. Most of the older geology of 서유럽(Western Europe) existed as part of the ancient microcontinent(microcontinent) Avalonia(Avalonia).

Geological history[편집]

The geological history of Europe traces back to the formation of the 발트 순상지(Baltic Shield) (Fennoscandia) and the Sarmatian craton(Sarmatian craton), both around 2.25 billion years ago, followed by the Volgo-Uralia(Volgo-Uralia) shield, the three together leading to the East European craton(East European craton) (≈ Baltica(Baltica)) which became a part of the 초대륙(supercontinent) 컬럼비아(Columbia). Around 1.1 billion years ago, Baltica and Arctica (as part of the 로렌시아(Laurentia) block) became joined to 로디니아(Rodinia), later resplitting around 550 million years ago to reform as Baltica. Around 440 million years ago 유라메리카(Euramerica) was formed from Baltica and Laurentia; a further joining with 곤드와나(Gondwana) then leading to the formation of Pangea(Pangea). Around 190 million years ago, Gondwana and 로라시아(Laurasia) split apart due to the widening of the Atlantic Ocean. Finally, and very soon afterwards, Laurasia itself split up again, into Laurentia (North America) and the Eurasian continent. The land connection between the two persisted for a considerable time, via 그린란드(Greenland), leading to interchange of animal species. From around 50 million years ago, rising and falling sea levels have determined the actual shape of Europe, and its connections with continents such as Asia. Europe's present shape dates to the late Tertiary period(Tertiary period) about five million years ago.[126]

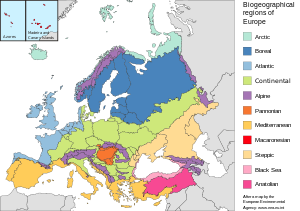

Biodiversity[편집]

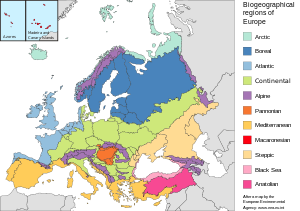

(Biogeographic regions) of Europe and bordering regions]]

Having lived side-by-side with agricultural peoples for millennia, Europe's animals and plants have been profoundly affected by the presence and activities of man. With the exception of 페노스칸디아(Fennoscandia) and northern Russia, few areas of untouched wilderness are currently found in Europe, except for various 국립공원(national park)s.

The main natural vegetation cover in Europe is mixed 숲(forest). The conditions for growth are very favourable. In the north, the 멕시코 만류(Gulf Stream) and North Atlantic Drift]](North Atlantic Drift) warm the continent. Southern Europe could be described as having a warm, but mild climate. There are frequent summer droughts in this region. Mountain ridges also affect the conditions. Some of these (알프스 산맥(Alps), 피레네 산맥(Pyrenees)) are oriented east-west and allow the wind to carry large masses of water from the ocean in the interior. Others are oriented south-north (스칸디나비아 산맥(Scandinavian Mountains), Dinarides]](Dinarides), 카르파티아 산맥(Carpathians), Apennines]](Apennines)) and because the rain falls primarily on the side of mountains that is oriented towards sea, forests grow well on this side, while on the other side, the conditions are much less favourable. Few corners of mainland Europe have not been grazed by 가축(livestock) at some point in time, and the cutting down of the pre-agricultural forest habitat caused disruption to the original plant and animal ecosystems.

Probably eighty to ninety per cent of Europe was once covered by forest.[127] It stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Arctic Ocean. Though over half of Europe's original forests disappeared through the centuries of deforestation(deforestation), Europe still has over one quarter of its land area as forest, such as the 타이가(taiga) of Scandinavia and Russia, mixed 우림(rainforest)s of the Caucasus and the Cork oak(Cork oak) forests in the western Mediterranean. During recent times, deforestation has been slowed and many trees have been planted. However, in many cases monoculture 플랜테이션 농업(plantation)s of conifers]](conifers) have replaced the original mixed natural forest, because these grow quicker. The plantations now cover vast areas of land, but offer poorer habitats for many European forest dwelling species which require a mixture of tree species and diverse forest structure. The amount of natural forest in Western Europe is just 2–3% or less, in European Russia 5–10%. The country with the smallest percentage of forested area (excluding the micronations(micronations)) is 아이슬란드(Iceland) (1%), while the most forested country is Finland (77%).[128]

In temperate Europe, mixed forest with both broadleaf]](broadleaf) and 구과식물(coniferous) trees dominate. The most important species in central and western Europe are beech(beech) and 참나무속(oak). In the north, the 타이가(taiga) is a mixed spruce(spruce)–소나무속(pine)–자작나무속(birch) forest; further north within Russia and extreme northern Scandinavia, the 타이가(taiga) gives way to 툰드라(tundra) as the Arctic is approached. In the Mediterranean, many 올리브(olive) trees have been planted, which are very well adapted to its arid climate; Mediterranean Cypress]](Mediterranean Cypress) is also widely planted in southern Europe. The semi-arid Mediterranean region hosts much scrub forest. A narrow east-west tongue of Eurasian 초원(grassland) (the 스텝(steppe)) extends eastwards from 우크라이나(Ukraine) and southern Russia and ends in Hungary and traverses into 타이가(taiga) to the north.

(Cave lion) became extinct in southeastern Europe about 2,000 years ago]]

Glaciation during the most recent 빙하기(ice age) and the presence of man affected the distribution of European fauna]](European fauna). As for the animals, in many parts of Europe most large animals and top predator(predator) species have been hunted to extinction. The woolly mammoth(woolly mammoth) was extinct before the end of the 신석기 시대(Neolithic) period. Today wolves]](wolves) (육식성(carnivore)s) and bears(bears) (omnivore(omnivore)s) are endangered. Once they were found in most parts of Europe. However, deforestation and hunting caused these animals to withdraw further and further. By the 중세(Middle Ages) the bears' habitats were limited to more or less inaccessible mountains with sufficient forest cover. Today, the brown bear]](brown bear) lives primarily in the 발칸 반도]](Balkan peninsula), Scandinavia, and Russia; a small number also persist in other countries across Europe (Austria, Pyrenees etc.), but in these areas brown bear populations are fragmented and marginalised because of the destruction of their habitat. In addition, 북극곰(polar bear)s may be found on 스발바르 제도(Svalbard), a Norwegian archipelago far north of Scandinavia. The wolf]](wolf), the second largest predator in Europe after the brown bear, can be found primarily in 동유럽(Eastern Europe) and in the Balkans, with a handful of packs in pockets of 서유럽(Western Europe) (Scandinavia, Spain, etc.).

European wild cat, foxes (especially the red fox), jackal and different species of martens, hedgehogs, different species of reptiles (like snakes such as vipers and grass snakes) and amphibians, different birds (owls, hawks and other birds of prey).

Important European herbivores are snails, larvae, fish, different birds, and mammals, like rodents, deer and roe deer, boars, and living in the mountains, marmots, steinbocks, chamois among others.

The extinction of the dwarf hippos]](dwarf hippos) and 난쟁이코끼리(dwarf elephant)s has been linked to the earliest arrival of humans on the islands of the Mediterranean(Mediterranean).

Sea creatures are also an important part of European flora and fauna. The sea flora is mainly phytoplankton(phytoplankton). Important animals that live in European seas are 동물성 플랑크톤(zooplankton), mollusc(mollusc)s, 극피동물(echinoderm)s, different 갑각류(crustacean)s, 오징어(squid)s and octopuses(octopuses), fish, 돌고래(dolphin)s, and whales(whales).

Biodiversity is protected in Europe through the 유럽 평의회(Council of Europe)'s Bern Convention]](Bern Convention), which has also been signed by the European Community(European Community) as well as non-European states.

Demographics[편집]

Since the 르네상스(Renaissance), Europe has had a major influence in culture, economics and social movements in the world. The most significant 발명(invention)s had their origins in the Western world, primarily Europe and the United States.[130] Some current and past issues in European demographics have included religious emigration]](religious emigration), race relations(race relations), economic immigration]](economic immigration), a declining 출생률(birth rate) and an aging population(aging population).

In some countries, such as 아일랜드 섬(Ireland) and Poland, access to 낙태(abortion) is currently limited; in the past, such restrictions and also restrictions on artificial birth control were commonplace throughout Europe. Abortion remains illegal on the island of 몰타(Malta) where Catholicism is the state religion. Furthermore, three European countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland) and the Autonomous Community(Autonomous Community) of 안달루시아 지방(Andalusia) (Spain)[131][132] have allowed a limited form of 안락사(voluntary euthanasia) for some terminally ill people.

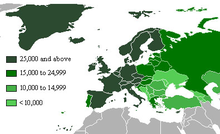

In 2005, the population of Europe was estimated to be 731 million according to the United Nations,[133] which is slightly more than one-ninth of the world's population. A century ago, Europe had nearly a quarter of the 세계 인구(world's population).[134] The population of Europe has grown in the past century, but in other areas of the world (in particular Africa and Asia) the population has grown far more quickly.[133] Among the continents, Europe has a relatively high 인구 밀도(population density), second only to Asia. The most densely populated country in Europe is the Netherlands, ranking third in the world after 방글라데시(Bangladesh) and South Korea. Pan and Pfeil (2004) count 87 distinct "peoples of Europe", of which 33 form the majority population in at least one sovereign state, while the remaining 54 constitute ethnic minorities]](ethnic minorities).[135]

According to UN population projection, Europe's population may fall to about 7% of world population by 2050, or 653 million people (medium variant, 556 to 777 million in low and high variants, respectively).[133] Within this context, significant disparities exist between regions in relation to fertility rates]](fertility rates). The average number of children per female]](children per female) of child bearing age is 1.52.[136] According to some sources,[137] this rate is higher among Muslims in Europe]](Muslims in Europe). The UN predicts the steady population decline(population decline) of vast areas of Eastern Europe.[138] The Russia's population is declining by at least 700,000 people each year.[139] The country now has 13,000 uninhabited villages.[140]

Europe is home to the highest number of migrants of all global regions at 70.6 million people, the IOM]](IOM)'s report said.[141] In 2005, the EU had an overall net gain from 이민(immigration) of 1.8 million people, despite having one of the highest 인구 밀도(population densities) in the world. This accounted for almost 85% of Europe's total population growth(population growth).[142] The European Union plans to open the job centres for legal migrant workers from Africa.[143][144] In 2008, 696,000 persons were given citizenship of an EU27 member state, a decrease from 707,000 the previous year. The largest groups that acquired citizenship of an EU member state were citizens of Morocco, Turkey, Ecuador, Algeria and Iraq.[145]

Emigration from Europe began with Spanish settlers in the 16th century, and French and English settlers in the 17th century.[146] But numbers remained relatively small until waves of mass emigration in the 19th century, when millions of poor families left Europe.[147]

Today, large populations of European descent are found on every continent. European ancestry predominates in North America, and to a lesser degree in South America (particularly in Argentina, 칠레(Chile), 우루과이(Uruguay) and Centro-Sul(Centro-Sul) of Brazil). Also, Australia and New Zealand have large European derived populations. Africa has no countries with European-derived majorities, but there are significant minorities, such as the White South African(White South African)s. In Asia, European-derived populations (specifically 러시아인(Russians)) predominate in Northern Asia(Northern Asia).

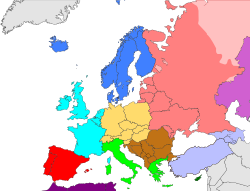

Political geography[편집]

According to different definitions, the territories may be subject to various categorisations]](various categorisations). The 27 European Union member state(European Union member state)s are highly integrated economically and politically; the European Union itself forms part of the political geography of Europe. The table below shows the scheme for geographic subregions]](scheme for geographic subregions) used by the United Nations,[148] alongside the regional grouping published in the CIA factbook(CIA factbook). The socio-geographical data included are per sources in cross-referenced articles.

| Name of country, with 깃발(flag) | 넓이]](Area) (km²) |

인구(Population) (1 July 2002 est.) |

인구 밀도]](Population density) (per km²) |

Capital]](Capital) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 틀:나라자료 Albania | 28,748 | 3,600,523 | 125.2 | 티라나(Tirana) |

| 틀:나라자료 Andorra | 468 | 68,403 | 146.2 | 안도라라베야(Andorra la Vella) |

| 틀:나라자료 Armenia [k] | 29,800 | 3,229,900 | 101 | 예레반(Yerevan) |

| 틀:나라자료 Austria | 83,858 | 8,169,929 | 97.4 | 빈(Vienna) |

| 틀:나라자료 Azerbaijan [l] | 86,600 | 9,000,000 | 97 | 바쿠(Baku) |

| 틀:나라자료 Belarus | 207,600 | 10,335,382 | 49.8 | 민스크(Minsk) |

| 틀:나라자료 Belgium | 30,510 | 10,274,595 | 336.8 | 브뤼셀(Brussels) |

| 틀:나라자료 Bosnia and Herzegovina | 51,129 | 4,448,500 | 77.5 | 사라예보(Sarajevo) |

| 틀:나라자료 Bulgaria | 110,910 | 7,621,337 | 68.7 | 소피아(Sofia) |

| 틀:나라자료 Croatia | 56,542 | 4,437,460 | 77.7 | 자그레브(Zagreb) |

| 틀:나라자료 Cyprus [e] | 9,251 | 788,457 | 85 | 니코시아(Nicosia) |

| 틀:나라자료 Czech Republic | 78,866 | 10,256,760 | 130.1 | 프라하(Prague) |

| 틀:나라자료 Denmark | 43,094 | 5,368,854 | 124.6 | 코펜하겐(Copenhagen) |

| 틀:나라자료 Estonia | 45,226 | 1,415,681 | 31.3 | 탈린(Tallinn) |

| 틀:나라자료 Finland | 336,593 | 5,157,537 | 15.3 | 헬싱키(Helsinki) |

| 틀:나라자료 France [h] | 547,030 | 59,765,983 | 109.3 | Paris |

| 틀:나라자료 Georgia [m] | 69,700 | 4,661,473 | 64 | 트빌리시(Tbilisi) |

| 틀:나라자료 Germany | 357,021 | 83,251,851 | 233.2 | Berlin |

| 틀:나라자료 Greece | 131,940 | 10,645,343 | 80.7 | 아테네(Athens) |

| 틀:나라자료 Hungary | 93,030 | 10,075,034 | 108.3 | 부다페스트(Budapest) |

| 틀:나라자료 Iceland | 103,000 | 307,261 | 2.7 | 레이캬비크(Reykjavík) |

| 틀:나라자료 Ireland | 70,280 | 4,234,925 | 60.3 | 더블린(Dublin) |

| 틀:나라자료 Italy | 301,230 | 58,751,711 | 191.6 | Rome |

| 틀:나라자료 Kazakhstan [j] | 2,724,900 | 15,217,711 | 5.6 | 아스타나(Astana) |

| 틀:나라자료 Latvia | 64,589 | 2,366,515 | 36.6 | 리가(Riga) |

| 틀:나라자료 Liechtenstein | 160 | 32,842 | 205.3 | 파두츠(Vaduz) |

| 틀:나라자료 Lithuania | 65,200 | 3,601,138 | 55.2 | 빌뉴스(Vilnius) |

| 틀:나라자료 Luxembourg | 2,586 | 448,569 | 173.5 | 룩셈부르크(Luxembourg) |

| 틀:나라자료 Republic of Macedonia | 25,713 | 2,054,800 | 81.1 | 스코페(Skopje) |

| 틀:나라자료 Malta | 316 | 397,499 | 1,257.9 | 발레타(Valletta) |

| 틀:나라자료 Moldova [b] | 33,843 | 4,434,547 | 131.0 | 키시너우(Chişinău) |

| 틀:나라자료 Monaco | 1.95 | 31,987 | 16,403.6 | 모나코(Monaco) |

| 틀:나라자료 Montenegro | 13,812 | 616,258 | 44.6 | 포드고리차(Podgorica) |

| 틀:나라자료 Netherlands [i] | 41,526 | 16,318,199 | 393.0 | 암스테르담(Amsterdam) |

| 틀:나라자료 Norway | 324,220 | 4,525,116 | 14.0 | 오슬로(Oslo) |

| 틀:나라자료 Poland | 312,685 | 38,625,478 | 123.5 | 바르샤바(Warsaw) |

| 틀:나라자료 Portugal [f] | 91,568 | 10,409,995 | 110.1 | 리스본(Lisbon) |

| 틀:나라자료 Romania | 238,391 | 21,698,181 | 91.0 | 부쿠레슈티(Bucharest) |

| 틀:나라자료 Russia [c] | 17,075,400 | 142,200,000 | 26.8 | Moscow |

| 틀:나라자료 San Marino | 61 | 27,730 | 454.6 | 산마리노]](San Marino) |

| 틀:나라자료 Serbia[149] | 88,361 | 7,495,742 | 89.4 | 베오그라드(Belgrade) |

| 틀:나라자료 Slovakia | 48,845 | 5,422,366 | 111.0 | 브라티슬라바(Bratislava) |

| 틀:나라자료 Slovenia | 20,273 | 1,932,917 | 95.3 | 류블랴나(Ljubljana) |

| 틀:나라자료 Spain | 504,851 | 45,061,274 | 89.3 | 마드리드(Madrid) |

| 틀:나라자료 Sweden | 449,964 | 9,090,113 | 19.7 | 스톡홀름(Stockholm) |

| 틀:나라자료 Switzerland | 41,290 | 7,507,000 | 176.8 | 베른(Bern) |

| 틀:나라자료 Turkey [n] | 783,562 | 71,517,100 | 93 | 앙카라(Ankara) |

| 틀:나라자료 Ukraine | 603,700 | 48,396,470 | 80.2 | 키예프(Kiev) |

| 틀:나라자료 United Kingdom | 244,820 | 61,100,835 | 244.2 | London |

| 틀:나라자료 Vatican City | 0.44 | 900 | 2,045.5 | 바티칸 시국(Vatican City) |

| Total | 10,180,000[o] | 731,000,000[o] | 70 |

Within the above-mentioned states are several regions, enjoying broad autonomy, as well as several 데 팍토(de facto) independent countries with limited international recognition or unrecognised. None of them are UN members:

| Name of territory, with 깃발(flag) | 넓이]](Area) (km²) |

인구(Population) (1 July 2002 est.) |

인구 밀도]](Population density) (per km²) |

Capital]](Capital) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 틀:나라자료 Abkhazia [r] | 8,432 | 216,000 | 29 | 수후미(Sukhumi) |

| 틀:나라자료 Åland (Finland) | 1,552 | 26,008 | 16.8 | 마리에함(Mariehamn) |

| 틀:나라자료 Faroe Islands (Denmark) | 1,399 | 46,011 | 32.9 | 토르스하운(Tórshavn) |

| 틀:나라자료 Gibraltar (UK) | 5.9 | 27,714 | 4,697.3 | 지브롤터(Gibraltar) |

| 틀:나라자료 Guernsey [d] (UK) | 78 | 64,587 | 828.0 | St. Peter Port(St. Peter Port) |

| 틀:나라자료 Isle of Man [d] (UK) | 572 | 73,873 | 129.1 | 더글러스(Douglas) |

| 틀:나라자료 Jersey [d] (UK) | 116 | 89,775 | 773.9 | 세인트헬리어(Saint Helier) |

| 틀:나라자료 Kosovo [p] | 10,887 | [150] 1,804,838 | 220 | 프리슈티나(Pristina) |

| 틀:나라자료 Nagorno-Karabakh | 11,458 | 138,800 | 12 | 스테파나케르트(Stepanakert) |

| 틀:나라자료 Northern Cyprus | 3,355 | 265,100 | 78 | 니코시아(Nicosia) |

| 틀:나라자료 South Ossetia [r] | 3,900 | 70,000 | 18 | 츠힌발리(Tskhinvali) |

Mayen Islands) (Norway) |

62,049 | 2,868 | 0.046 | 롱위에아르뷔엔(Longyearbyen) |

| 틀:나라자료 Transnistria [b] | 4,163 | 537,000 | 133 | 티라스폴(Tiraspol) |

Economy[편집]

As a continent, the economy of Europe is currently the largest on Earth and it is the richest region as measured by assets under management with over $32.7 trillion compared to North America's $27.1 trillion in 2008.[151] In 2009 Europe remained the wealthiest region. Its $37.1 trillion in assets under management represented one-third of the world’s wealth. It was one of several regions where wealth surpassed its precrisis year-end peak.[152] As with other continents, Europe has a large variation of wealth among its countries. The richer states tend to be in the 서쪽(West); some of the 동유럽(Eastern) economies are still emerging from the collapse of the 소비에트 연방(Soviet Union) and 유고슬라비아(Yugoslavia).

The European Union, an intergovernmental body composed of 27 European states, comprises the largest single economic area]](largest single economic area) in the world. Currently, 16 EU 나라(countries) share the 유로(euro) as a common currency. Five European countries rank in the top ten of the worlds largest national economies in GDP (PPP)]](national economies in GDP (PPP)). This includes (ranks according to the CIA]](CIA)): Germany (5), the UK (6), Russia (7), France (8), and Italy (10).[153]

Pre–1945: Industrial growth[편집]

Capitalism has been dominant in the Western world since the end of feudalism.[154] From Britain, it gradually spread throughout Europe.[155] The 산업 혁명(Industrial Revolution) started in Europe, specifically the United Kingdom in the late 18th century,[156] and the 19th century saw Western Europe industrialise. Economies were disrupted by World War I but by the beginning of World War II they had recovered and were having to compete with the growing economic strength of the United States. World War II, again, damaged much of Europe's industries.

1945–1990: The Cold War[편집]

After World War II the economy of the UK was in a state of ruin,[157] and continued to suffer relative economic decline in the following decades.[158] Italy was also in a poor economic condition but regained a high level of growth by the 1950s. West Germany recovered quickly]](recovered quickly) and had doubled production from pre-war levels by the 1950s.[159] France also staged a remarkable comeback enjoying rapid growth and modernisation; later on Spain, under the leadership of 프란시스코 프랑코(Franco), also recovered, and the nation recorded huge unprecedented economic growth beginning in the 1960s in what is called the Spanish miracle(Spanish miracle).[160] The majority of 동유럽(Eastern Europe)an states came under the control of the USSR(USSR) and thus were members of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance(Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) (COMECON).[161]

The states which retained a free-market(free-market) system were given a large amount of aid by the United States under the 유럽 부흥 계획(Marshall Plan).[162] The western states moved to link their economies together, providing the basis for the EU and increasing cross border trade. This helped them to enjoy rapidly improving economies, while those states in COMECON were struggling in a large part due to the cost of the 냉전(Cold War). Until 1990, the European Community(European Community) was expanded from 6 founding members to 12. The emphasis placed on resurrecting the West German economy led to it overtaking the UK as Europe's largest economy.

1991–2007: Integration and reunification[편집]

With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1991 the Eastern states had to adapt to a free market system. There were varying degrees of success with 중앙유럽(Central Europe)an countries such as Poland, Hungary, and 슬로베니아(Slovenia) adapting reasonably quickly, while eastern states like 우크라이나(Ukraine) and Russia taking far longer. Western Europe helped Eastern Europe by forming economic ties with it.[출처 필요]

After 동쪽(East) and West Germany were reunited in 1990, the economy of West Germany struggled as it had to support and largely rebuild the infrastructure of East Germany. Yugoslavia lagged farthest behind as it was ravaged by war and in 2003 there were still many EU and 북대서양 조약 기구(NATO) peacekeeping troops in 코소보(Kosovo), the 마케도니아 공화국(Republic of Macedonia), and 보스니아 헤르체고비나(Bosnia and Herzegovina), with only 슬로베니아(Slovenia) making any real progress.

By the millennium change, the EU dominated the economy of Europe comprising the five largest European economies of the time namely Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Spain. In 1999 12 of the 15 members of the EU joined the 유로존(Eurozone) replacing their former national currencies by the common 유로(euro). The three who chose to remain outside the Eurozone were: the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden.

2008–2010: Recession[편집]

The Eurozone entered its first official 경기후퇴(recession) in the third quarter of 2008, official figures confirmed in January 2009.[163] While beginning in the United States the late-2000s recession(late-2000s recession) spread to Europe rapidly and has affected much of the region.[164] The official 실업(unemployment) rate in the 16 countries that use the euro rose to 9.5% in May 2009.[165] Europe's young workers have been especially hard hit.[166] In the first quarter of 2009, the unemployment rate in the EU27(EU27) for those aged 15–24 was 18.3%.[167]

In early 2010 fears of a sovereign debt crisis]](sovereign debt crisis)[168] developed concerning some countries in Europe, especially Greece, Ireland, Spain, and Portugal.[169] As a result, measures were taken especially for Greece by the leading countries of the Eurozone.[170]

Language[편집]

European languages mostly fall within three Indo-European]](Indo-European) language groups: the 로망스어군(Romance languages), derived from the Latin language(Latin language) of the 로마 제국(Roman Empire); the 게르만어파(Germanic languages), whose ancestor language came from southern Scandinavia; the 발트어파(Baltic languages) and the 슬라브어파(Slavic languages).[126] While having the majority of its vocabulary descended from Romance languages, the 영어(English language) is classified as a Germanic language.

Romance languages are spoken primarily in south-western Europe as well as in 루마니아(Romania) and 몰도바(Moldova). Germanic languages are spoken in north-western Europe and some parts of 중앙유럽(Central Europe). Slavic languages are spoken in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe.[126]

Many other languages outside the three main groups exist in Europe. Other Indo-European languages include the 발트어파(Baltic) group (i.e., Latvian]](Latvian) and Lithuanian]](Lithuanian)), the Celtic]](Celtic) group (i.e., Irish, 스코틀랜드 게일어]](Scottish Gaelic), Manx]](Manx), Welsh, Cornish]](Cornish), and Breton]](Breton)[126]), 그리스어(Greek), 알바니아어(Albanian), and Armenian]](Armenian). A distinct group of 우랄어족(Uralic languages) are Estonian]](Estonian), Finnish, and Hungarian, spoken in the respective countries as well as in parts of Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Slovakia. Other Non-Indo-European languages are 몰타어(Maltese) (the only Semitic language(Semitic language) official to the EU), Basque]](Basque), Georgian]](Georgian), Azerbaijani]](Azerbaijani), 터키어(Turkish) in 동트라키아(Eastern Thrace), and the languages of minority nations in Russia.

Multilingualism and the protection of regional and minority languages are recognised political goals in Europe today. The 유럽 평의회(Council of Europe) Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities(Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities) and the 유럽 평의회(Council of Europe)'s European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages(European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages) set up a legal framework for language rights in Europe.

Religion[편집]

Historically]](Historically), religion in Europe has been a major influence on European art]](European art), 문화]](culture), 철학]](philosophy) and 법]](law). The majority religion in Europe is Christianity as practiced by Catholic, 동방 정교회(Eastern Orthodox) and Protestant]](Protestant) Churches. Following these is 이슬람교(Islam) concentrated mainly in the south east (보스니아 헤르체고비나(Bosnia and Herzegovina), 알바니아(Albania), 코소보(Kosovo), 카자흐스탄(Kazakhstan), North Cyprus]](North Cyprus), 터키(Turkey) and 아제르바이잔(Azerbaijan)), and Tibetan]](Tibetan) 불교(Buddhism), found in 칼미크 공화국(Kalmykia). Other religions including Judaism and 힌두교(Hinduism) are minority religions. Europe is a relatively secular continent and has the largest number and proportion of irreligious]](irreligious), agnostic]](agnostic) and atheistic]](atheistic) people in the 서양]](Western world), with a particularly high number of self-described non-religious people in the Czech Republic, 에스토니아(Estonia), Sweden, Germany (East), and France.[171]

Culture[편집]

The culture of Europe can be described as a series of overlapping cultures; cultural mixes exist across the continent. There are cultural 혁신(innovation)s and movements, sometimes at odds with each other. Thus the question of "common culture" or "common values" is complex.

See also[편집]

- Communications in Europe(Communications in Europe)

- 유럽 대륙(Continental Europe)

- Europe as a potential superpower]](Europe as a potential superpower)

- Europa Nostra(Europa Nostra)

- List of European countries in order of geographical area(List of European countries in order of geographical area)

- List of European television stations(List of European television stations)

- Politics

- Alternative names of European cities]](Alternative names of European cities)

- 유럽 평의회(Council of Europe)

- Eurodistrict(Eurodistrict)

- 유럽 연합(European Union)

- Euroregion(Euroregion)

- 유럽회의주의(Euroscepticism)

- Flags of Europe(Flags of Europe)

- International Organisations in Europe(International Organisations in Europe)

- List of European sovereign states by date of achieving sovereignty(List of European sovereign states by date of achieving sovereignty)

- OSCE]](OSCE)

- OSCE countries statistics]](OSCE countries statistics)

- Demographics

- Area and population of European countries(Area and population of European countries)

- Demography of Europe(Demography of Europe)

- European American(European American)

- European ethnic groups(European ethnic groups)

- European Union Statistics(European Union Statistics)

- Largest cities of the EU]](Largest cities of the EU)

- Largest European metropolitan areas(Largest European metropolitan areas)

- Largest urban areas of the EU]](Largest urban areas of the EU)

- List of cities in Europe by country(List of cities in Europe by country)

- List of villages in Europe by country(List of villages in Europe by country)

- List of European countries by population(List of European countries by population)

- Economics

Notes[편집]

이 문서의 내용은 출처가 분명하지 않습니다. |

^ a: Continental regions as per UN categorisations/map. Depending on definitions, various territories cited below may be in one or both of]](one or both of) Europe and Asia, or Africa.

^ b: 트란스니스트리아(Transnistria), internationally recognised as being a legal part of the Republic of Moldova(Republic of Moldova), although de facto control is exercised by its internationally unrecognised government which declared independence from Moldova in 1990.

^ c: Russia is considered a transcontinental country in Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. However the population and area figures include the entire state.

^ d: 건지 섬(Guernsey), the 맨 섬(Isle of Man) and 저지 섬(Jersey) are Crown Dependencies(Crown Dependencies) of the 영국(United Kingdom). Other 채널 제도(Channel Islands) legislated by the Bailiwick of Guernsey(Bailiwick of Guernsey) include 올더니 섬(Alderney) and 사크 섬(Sark).

^ e: 키프로스(Cyprus) is sometimes considered transcontinental country. Physiographically entirely in 서남아시아(Western Asia) it has strong historical and sociopolitical connections with Europe. The population and area figures refer to the entire state, including the de facto independent part 북키프로스 터키 공화국(Northern Cyprus).

^ f: Figures for 포르투갈(Portugal) include the 아소르스 제도(Azores) and 마데이라 제도(Madeira) archipelagos, both in Northern Atlantic(Northern Atlantic).

^ g: Figures for 세르비아(Serbia) include 코소보(Kosovo), a province that unilaterally declared its independence from 세르비아(Serbia) on 17 February 2008, and whose sovereign status is unclear.

^ h: Figures for 프랑스(France) include only 프랑스 본토(metropolitan France): some politically integral parts of France]](politically integral parts of France) are geographically located outside Europe.

^ i: 네덜란드(Netherlands) population for July 2004. Population and area details include European portion only: Netherlands and two entities outside Europe (아루바(Aruba) and the 네덜란드령 안틸레스(Netherlands Antilles), in the 카리브 제도(Caribbean)) constitute the 네덜란드 왕국(Kingdom of the Netherlands). 암스테르담(Amsterdam) is the official capital, while 헤이그(The Hague) is the administrative seat.

^ j: 카자흐스탄(Kazakhstan) is physiographically considered a transcontinental country in Central Asia (UN region) and Eastern Europe, with European territory west of the Ural Mountains and both the 우랄(Ural) and 엠바 강(Emba) rivers. However, area and population figures refer to the entire country.

^ k: 아르메니아(Armenia) is physiographically entirely in 서남아시아(Western Asia), but it has strong historical and sociopolitical connections with Europe. The population and area figures include the entire state respectively.

^ l: 아제르바이잔(Azerbaijan) is often considered a transcontinental country in Eastern Europe and Western Asia. However the population and area figures are for the entire state. This includes the exclave(exclave) of 나히체반(Nakhchivan) and the region 나고르노카라바흐(Nagorno-Karabakh) that has declared, and 데 팍토(de facto) achieved]](achieved), independence. Nevertheless, it is not recognised 데 유레(de jure) by 국가(sovereign state)s.

^ m: 조지아(Georgia) is often considered a transcontinental country in Western Asia and Eastern Europe. However, the population and area figures include the entire state. This also includes Georgian estimates for 압하스(Abkhazia) and 남오세티야(South Ossetia), two regions that have declared and 데 팍토(de facto) achieved]](achieved) independence. The International recognition]](International recognition), however, is limited.

^ n: 터키(Turkey) is physiographically considered a transcontinental country in Western Asia and Eastern Europe. However the population and area figures include the entire state, both the European and Asian portions.

^ o: The total figures for area and population include only European portions of transcontinental countries. The precision of these figures is compromised by the ambiguous geographical extent of Europe and the lack of references for European portions of transcontinental countries.

^ p: 코소보(Kosovo) unilaterally declared its independence from 세르비아(Serbia) on 17 February 2008. Its sovereign status is unclear]](unclear). Its population is July 2009 CIA estimate.

^ r: 압하스(Abkhazia) and 남오세티야(South Ossetia) unilaterally declared their independence from 조지아(Georgia) on 25 August 1990 and 28 November 1991 respectively. Their sovereign status is unclear]](unclear). Population figures stated as of 2003 census and 2000 estimates respectively.

^ Russia Khazakstan: Russia and Khazakstan are first and second largest but both these figures include European and Asian territories

References[편집]

- ↑ OED Online]](OED Online) gives the pronunciation of "Europe" as: Brit. /ˈjʊərəp/, /ˈjɔːrəp/, U.S. /ˈjərəp/, /ˈjurəp/.

- ↑ 《National Geographic Atlas of the World》 7판. Washington, DC: 내셔널 지오그래픽(National Geographic). 1999. ISBN 0-7922-7528-4. "Europe" (pp. 68-9); "Asia" (pp. 90-1): "A commonly accepted division between Asia and Europe ... is formed by the Ural Mountains, Ural River, Caspian Sea, Caucasus Mountains, and the Black Sea with its outlets, the Bosporus and Dardanelles."

- ↑ Lewis & Wigen 1997, 226쪽 괄호 없는 하버드 인용 error: 여러 대상 (2×): CITEREFLewisWigen1997 (help)

- ↑ 가 나 National Geographic, 534.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Wigen, Kären (1997). “The myth of continents: a critique of metageography”. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ Jordan-Bychkov, Terry G.; Jordan, Bella Bychkova (2001). 《The European culture area: a systematic geography》. Rowman & Littlefield(Rowman & Littlefield). ISBN 0742516288.

- ↑ Herodotus, 4:45

- ↑ Franxman, Thomas W. (1979). 《Genesis and the Jewish antiquities of Flavius Josephus》. Pontificium Institutum Biblicum. 101–102쪽. ISBN 8876533354.

- ↑ Norman F. Cantor(Norman F. Cantor), The Civilization of the Middle Ages, 1993, ""Culture and Society in the First Europe", pp185ff.

- ↑ Noted by Cantor, 1993:181.

- ↑ Lewis & Wigen 1997, 23–25쪽 괄호 없는 하버드 인용 error: 여러 대상 (2×): CITEREFLewisWigen1997 (help)

- ↑ 《Europe: A History, by Norman Davies, p. 8》. Books.google.com. 1996. ISBN 9780198201717. 2010년 8월 23일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lewis & Wigen 1997, 27–28쪽 괄호 없는 하버드 인용 error: 여러 대상 (2×): CITEREFLewisWigen1997 (help)

- ↑ 가 나 Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopaedia 2007. 《Europe》. 2009년 10월 31일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ See, e.g., Merje Kuus, 'Europe's eastern expansion and the re-inscription of otherness in East-Central Europe' Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 28, No. 4, 472–489 (2004), József Böröcz, 'Goodness Is Elsewhere: The Rule of European Difference', Comparative Studies in Society and History, 110–36, 2006, or Attila Melegh, On the East-West Slope: Globalisation, nationalism, racism and discourses on Central and Eastern Europe, Budapest: Central European University Press, 2006.

- ↑ “About the Council of Europe”. Council of Europe. 2008년 5월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2008년 6월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Europe — Noun”. Princeton University. 2008년 6월 9일에 확인함. [깨진 링크]

- ↑ The map shows one of the most commonly accepted delineations of the geographical boundaries of Europe, as used by 내셔널 지오그래픽(National Geographic) and 브리태니커 백과사전(Encyclopaedia Britannica). Whether countries are considered in Europe or Asia can vary in sources, for example in the classification of the 월드 팩트북(CIA World Factbook) or that of the BBC(BBC).

- ↑ Minor theories, such as the (probably folk-etymological) one deriving Europa from ευρως "mould" aren't discussed in the section

- ↑ M. L. West (2007). 《Indo-European poetry and myth》. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press(Oxford University Press). 178–179쪽. ISBN 0-19-928075-4.

- ↑ “Etymonline: European”. 2006년 9월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ M. L. West (1997). 《The east face of Helicon: west Asiatic elements in Greek poetry and myth》. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 451쪽. ISBN 0-19-815221-3.

- ↑ Davidson, Roderic H. (1960). “Where is the Middle East?”. 《Foreign Affairs》 38: 665–675.

- ↑ A. Vekua, D. Lordkipanidze, G. P. Rightmire, J. Agusti, R. Ferring, G. Maisuradze; 외. (2002). “A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia”. 《Science》 297 (5578): 85–9. doi:10.1126/science.1072953. PMID 12098694.

- ↑ The million year old tooth from Atapuerca](Atapuerca), 스페인(Spain), found in June 2007]

- ↑ National Geographic, 21.

- ↑ Scarre, Chris (1996). “The Oxford Companion to Archaeology”. Oxford University Press(Oxford University Press): 215–216. ISBN 0195076184.

|id=에 templatestyles stripmarker가 있음(위치 1) (도움말) - ↑ Atkinson]](Atkinson), R J C, Stonehenge (Penguin Books(Penguin Books), 1956)

- ↑ Peregrine, Peter Neal; Ember, Melvin (2001). 《Encyclopaedia of Prehistory》. Springer. 157–184쪽. ISBN 0306462583., European Megalithic

- ↑ 가 나 National Geographic, 76.

- ↑ National Geographic, 82.

- ↑ Heath, Thomas Little (1981). 《A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I》. Dover Publications(Dover Publications). ISBN 0486240738.

- ↑ Heath, Thomas Little (1981). 《A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume II》. Dover publications. ISBN 0486240746.

- ↑ Pedersen, Olaf. Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press(Cambridge University Press), 1993.

- ↑ National Geographic, 76–77.

- ↑ 가 나 McEvedy, Colin (1961). 《The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History》. Penguin Books.

- ↑ National Geographic, 123.

- ↑ Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- ↑ , Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan., 1943), pp. 69–74.

- ↑ Norman F. Cantor]](Norman F. Cantor), The Medieval World 300 to 1300.

- ↑ National Geographic, 143–145.

- ↑ National Geographic, 162.

- ↑ National Geographic, 166.

- ↑ National Geographic, 135.

- ↑ National Geographic, 211.

- ↑ 가 나 National Geographic, 158.

- ↑ National Geographic, 186.

- ↑ National Geographic, 192.

- ↑ National Geographic, 199.

- ↑ Klyuchevsky, Vasily (1987). 《The course of the Russian history》. v.1: "Myslʹ. ISBN 5-244-00072-1.

- ↑ “The Destruction of Kiev”. University of Toronto. 2008년 6월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Khanate of the Golden Horde (Kipchak)”. Alamo Community Colleges. 2008년 6월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ The Late Middle Ages. Oglethorpe University.

- ↑ Baumgartner, Frederic J. France in the Sixteenth Century. London: MacMillan Publishers]](MacMillan Publishers), 1995. ISBN 0-333-62088-7.

- ↑ Don O'Reilly. "Hundred Years' War: Joan of Arc and the Siege of Orléans". TheHistoryNet.com.

- ↑ Poor studies will always be with us. By James Bartholomew. Telegraph. 7 August. 2004.

- ↑ Famine. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ “Plague, Plague Information, Black Death Facts, News, Photos– National Geographic”. Science.nationalgeographic.com. 2008년 11월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ National Geographic, 223.

- ↑ “Epidemics of the Past: Bubonic Plague — Infoplease.com”. Infoplease.com. 2008년 11월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Jo Revill (2004년 5월 16일). “Black Death blamed on man, not rats | UK news | The Observer”. London: The Observer. 2008년 11월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ National Geographic, 159.

- ↑ Weiss, Roberto]](Weiss, Roberto) (1969) The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, ISBN 1-59740-150-1

- ↑ 야코프 부르크하르트(Jacob Burckhardt) (1990) [1878]. 《The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy》 translation by S.G.C Middlemore판. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044534-X.

- ↑ National Geographic, 254.

- ↑ Jensen, De Lamar (1992), Renaissance Europe, ISBN 0-395-88947-2

- ↑ Levey, Michael (1967). 《Early Renaissance》. Penguin Books.

- ↑ National Geographic, 292.

- ↑ Levey, Michael (1971). 《High Renaissance》. Penguin Books.

- ↑ National Geographic, 193.

- ↑ National Geographic, 256–257.

- ↑ History of Europe – Demographics. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ National Geographic, 269.

- ↑ “The Seventeenth-Century Decline”. The Library of Iberian resources online. 2008년 8월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ "Food, Famine And Fertilizers". Seshadri Kannan (2009). APH Publishing. p.51. ISBN 813130356X

- ↑ John Morris Roberts (1997). 《Penguin History of Europe》. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140265619.

- ↑ National Geographic, 296.

- ↑ National Geographic, 338.

- ↑ Goldie, Mark; Wokler, Robert (2006). 《The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Political Thought》. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521374227.

- ↑ Cassirer, Ernst (1979). 《The Philosophy of the Enlightenment》. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691019630.

- ↑ National Geographic, 255.

- ↑ Schama, Simon (1989). 《Citizens: a chronicle of the French revolution》. Knopf]](Knopf). ISBN 0394559487.

- ↑ National Geographic, 360.

- ↑ McEvedy, Colin (1972). 《The Penguin Atlas of Modern History》. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140511539.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (1994). 《Napoleon Bonaparte and the legacy of the French Revolution》. St. Martin's Press(St. Martin's Press). ISBN 0312121237.