우주론 연표

| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 물리 우주론 |

|---|

|

대폭발(빅뱅) · 우주 우주의 나이 우주의 역사 |

|

|

이 우주론적 발견들 및 이론들의 연표인 우주론 연표(Timeline of cosmological theories)는 지난 2천 년 이상에 걸쳐 우주에 대한 인류의 이해의 발전에 대한 연대학적 기록이다. 현대 우주론적 사상들은 물리 우주론의 과학 분야의 발전에 따르고 있다.

수천 년 동안, 오늘날 태양계로 알려진 것은 수 세대에 걸쳐 "전체 우주"의 내용으로 간주되었기 때문에, 두 가지 지식의 발전은 대부분 평행하게 이루어졌다. 17세기 중반까지는 명확한 구분이 이루어지지 않았다. 이 부분에 대한 자세한 내용은 태양계 천문학 연표(Timeline of Solar System astronomy)를 참조하라.

고대[편집]

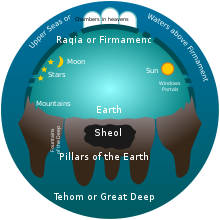

- 약 기원전 16세기 - 메소포타미아 우주론은 한 우주 바다(Cosmic ocean)에 둘러싸인 한 평평하고 원형인 지구를 가지고 있다.[1]

- 약 기원전 15세기에서 11세기 - 힌두교의 리그베다에는 우주론적 찬송가가 있으며, 특히 10권 후반부에는 우주의 기원을 설명하는 나사디야 수크타(Nasadiya Sukta)가 있는데, 이는 일원론적인 히라니가르바(Hiranyagarbha) 또는 "황금알"에서 유래한 것이다. 원초적 물질은 311조 4,000억 년 동안 현현하며, (다음) 동일한 기간 동안은 비현현한다. 우주는 43억 2천만 년 동안 현현 상태며, (다음) 동일한 기간 동안은 비현현한다. 무수한 우주들이 동시에 존재한다. 이러한 주기들은 영원히 지속될 것인데, 이것들은 욕구들에 의해서 주도된다.

- 기원전 6세기 – 바빌로니아 세계 지도(Babylonian Map of the World)는 우주의 바다로 둘러싸인 지구와 더불어, 그 주위에 일곱 개의 섬이 배열되어 일곱 개의 별 모양을 형성하는 것을 보여준다. 현대 성서 우주론(Biblical cosmology)은 물 위를 유영하는 평평하고 둥근 지구와 별들이 고정되어 있는 궁창의 견고한 둥근 천장으로 덮여 있다는 동일한 관점을 반영한다.

- 기원전 6-4세기 - 일찌기 그리스 철학자 아낙시만드로스는[2] 다중 또는 심지어 무한 우주들의 개념을 도입한다.[3] 데모크리토스는 더 나아가 이 세계들이 거리, 크기에서 다양하고; 태양과 달의 존재, 수, 크기 등에서 다양하며; 파괴적인 충돌의 대상이 된다고 자세히 설명했다.[4] 또한 이 기간 동안 그리스인들은 지구가 평평하지 않고 구형이라는 것을 확립했다.[5][6]

- 기원전 6세기 - 아낙시만드로스는 한 기계적이고 비신화적인 세계의 모형을 착상한다: 지구는 무한의 중심에 매우 고요하게 떠 있으며, 아무것에 의해 지지되지 않는다.[7] 그것의 특이한 모양은 지름의 3분의 1 높이의 원통[8]과 같다. 평평한 꼭대기는 원형의 해양 덩어리로 둘러싸인 사람이 사는 세계를 형성한다. 아낙시만드로스는 태양을 (펠러폰네소스 땅보다 더 큰[9]) 거대한 천체로 생각했고, 그 결과 태양이 지구로부터 얼마나 멀리 떨어져 있는지를 깨달았다. 그의 시스템에서 천체들은 서로 다른 거리에서 회전했다. 원점에는, 뜨거운 것과 차가운 것이 분리된 후 나무 껍질처럼 지구를 둘러싸고 있는 한 불꽃의 공이 나타났다. 이 공은 부셔져 우주의 나머지 부분을 형성했다. 그것은 마치 피리처럼 구멍으로 뚫린 테가 있는 불로 가득 찬 텅 빈 동심 바퀴 시스템과 비슷했다. 따라서, 태양은 가장 먼 바퀴에 있는 지구와 같은 크기의 구멍을 통해 볼 수 있는 불이었고, 일식은 그 구멍의 엄폐와 일치했다. 태양 바퀴의 지름은 지구의 27배(또는 28배, 출처에 따라 다르지만)[10]였고, 불의 강도가 덜한 달 바퀴의 지름은 18배(또는 19배)였다. 그것의 구멍은 모양을 바꿀 수 있었고, 이렇게 달의 위상을 설명할 수 있었다. 별들과 행성들은[11] 더 가까운 곳에 위치했으며, 같은 모형을 따랐다.[12]

- 기원전 5세기 – 파르메니데스는 지구가 구형이며 우주의 중심에 위치한다고 선언한 최초의 그리스인으로 믿어지고 있다.[13]

- 기원전 5세기 - 필롤라오스와 같은 피타고라스 학파들은 행성들의 운동이 행성의 동력이 되는 우주의 중심부(태양이 아닌)에서 보이지 않는 "불"에 의해 야기된다고 믿었고, 태양과 지구는 다른 거리들에서 중심부의 불을 공전한다. 지구의 사람이 사는 쪽은 항상 중앙 불의 반대편에 있으며, 이는 사람들이 그것을 볼 수 없도록 만든다. 그들은 또한 달과 행성들이 지구 주위를 돈다고 주장했다.[14] 이 모형은 움직이는 지구를 묘사하는데, 동시에 자전하면서 (태양 주위가 아닌) 한 외부 점 주위를 공전하기 때문에, 일반적인 직관과는 반대로 지구중심적이지 않다. 숫자 10(피타고라스 학파에게는 "완벽한 수(perfect number)")에 대한 철학적 우려 때문에, 그들은 또한 보이지 않는 중심 불의 반대쪽에 항상 있고 따라서 지구에서도 보이지 않는 10번째 "숨겨진 몸체" 또는 "반대쪽 지구"(Antichthon)를 추가했다.[15]

- 기원전 4세기 – 플라톤은 그의 《티마이오스》에서 원들과 구들이 우주의 선호되는 모양이며, 지구가 중심에 있고 다음에 의해서 안쪽에서 바깥쪽으로 순서대로 원을 그린다고 주장했다: 달, 태양, 금성, 수성, 화성, 목성, 토성, 그리고 마지막으로 천구에 위치한 고정된 별들(fixed stars).[16] 플라톤의 복잡한 우주기원론에서,[17] 데미우르고스는 동일성의 운동에 우선권을 부여하고 그것을 분할되지 않은 상태로 두었다; 그러나 그는 차이의 운동을 여섯 부분으로 나누어, 일곱 개의 다른 원들을 갖도록 했다. 그는 이 원들이 서로 반대 방향들로 움직이도록 하여, 그 중 세 개는 같은 속도로, 다른 하나는 속도가 다르지만 항상 비례적으로 움직이도록 규정했다. 이 원들은 천체들의 궤도들다. 같은 속도로 움직이는 세 개는 태양, 금성 및 수성이며, 다른 속도로 움직이는 네 개는 달, 화성, 목성 및 토성이다.[18][19] 이러한 움직임들의 복잡한 패턴은 '완전한' 또는 '완벽한' 해라는 기간이 지나면 다시 반복될 수밖에 없다.[20] 그러나 필롤라오스 및 히세타스Hicetas와 같은 다른 사람들은 지구중심설을 거부했다.[21]

- 기원전 4세기 – 크니도스의 에우독시스는 행성들의 움직임에 대한 한 기하학적-수학적 모형들을 고안했는데, 지구를 중심으로 하는 (개념적) 동심구(Concentric spheres)를 기반으로 하는, 이는 이러한 의미에서, 최초로 알려진 노력이였다.[22] 태양과 달의 움직임과 함께 행성들의 움직임의 복잡성을 설명하기 위해 에우독소스는 행성들이 마치 눈에 보이지 않는 개념적인, 눈에 보이지 않는 동심구(Concentric spheres)들에 붙어 있는 것처럼 움직이며. 각 구는 자신 및 다른 축을 중심으로 다른 속도들로 회전한다고 생각했다. 그의 모형은 각 천체에 대해 관찰 가능한 운동의 한 유형을 설명하는 각 구와 함께하는 27가지 동심구들을 갖고 있었다. 에우독소스는 이것은 각 천체의 구체가 존재하지 않는다는 의미에서 모형의 한 순전히 수학적 구성이며, 그것이 바로 천체들의 가능한 위치들을 보여줄 뿐이라는 것을 강조했다.[23] 그의 모형은 나중에 칼리푸스Callippus에 의해 개선되고 확장되었다.

- 기원전 4세기 – 아리스토텔레스는 지구가 고정되어 있고 코스모스(또는 우주)가 크기는 유한하지만 시간은 무한하다는 플라톤의 지구 중심 우주를 따른다. 그는 월식[24] 및 기타 관측을 사용하여 구형 지구를 주장했다. 아리스토텔레스는 이전의 에우독소스와 칼리푸스의 모형을 훨씬 더 채택하고 확장했지만 그 구들이 물질적이고 결정체라고 가정했다.[25] 아리스토텔레스는 또한 지구가 움직이는지 여부를 확인하려고 노력했고 모든 천체는 자연적 경향에 의해 지구를 향해 떨어지고 지구가 그 경향의 중심이기 때문에 정지해 있다고 결론지었다.[26] 플라톤은 우주에 시작이 있었다고 모호하게 주장한 것 같지만 아리스토텔레스와 다른 사람들은 플라톤의 말을 다르게 해석했다.[27]

- 기원전 4세기 - 《데 문도(De Mundo)》 - 5개 지역의 구체에 위치한 다섯 원소들은, 다섯 지역의 구체에 위치하며, 각각 경우에 작은 원소가 큰 원소에 둘러싸여 있어서 - 즉, 지구는 물로 둘러싸여 있고, 물은 공기로, 공기는 불로, 불은 아이테르로 둘러싸여 있어서 - 전체 우주를 구성한다.[28]

- 기원전 4세기 – 헤라클레이데스 폰티쿠스Heraclides Ponticus는 아리스토텔레스의 가르침에 반하여 서쪽에서 동쪽으로 24시간마다 지구가 자전한다고 제안한 최초의 그리스인이라고 알려져 있다. 심플리시우스Simplicius는 헤라클레이데스가 만일 태양이 정지해 있는 동안 지구가 움직인다면, 행성들의 불규칙한 움직임이 설명될 수 있다고 제안했다고 말하지만,[29] 그러나 이러한 진술은 논란의 여지가 있다.[30]

- 기원전 3세기 – 사모스의 아리스타르코스는 태양 중심 우주와 자체 축에서 지구 자전을 제안한다. 그는 또한 자신의 관찰에서 자신의 이론에 대한 증거를 제공한다.[31]

- 기원전 3세기 – 아르키메데스는 그의 에세이 《모래알을 세는 사람》에서 만일 우주의 지름이 아리스타르쿠스의 이론이 맞다면, 현대에 2광년이라고 불릴 것과 같은 스타디아(stadia)와 같읕 것이라고 추정한다.

- 기원전 2세기 – 셀레우키아의 셀레우코스는 태양중심설을 설명하기 위해 조수 현상을 사용하여 아리스타코스의 태양중심 우주에 대해 자세히 설명한다. 셀레우코스는 추론을 통해 태양 중심계를 최초로 증명한 사람이다. 태양중심 우주론에 대한 셀레우코스의 주장은 아마도 조석 현상과 관련이 있었을 것이다. 스트라보Strabo(1.1.9)에 따르면 셀레우코스는 조석이 달의 인력 때문이며 조석의 높이는 태양에 대한 달의 위치에 따라 다르다고 처음으로 언급했다. 대안적으로는, 기하학적 모형의 상수를 결정하여 태양중심설을 증명했을 수도 있다.[32]

- 기원전 2세기 – 페르게의 아폴로니오스는 겉보기 역행 운동(지구중심 모형을 가정)에 대한 두 가지 설명의 동등성을 보여준다. 하나는 이심률을 사용하고 다른 하나는 대원과 주전원(Deferent and epicycle)을 사용한다.[33] 후자는 미래 모형의 핵심 기능이 될 것이다. 주전원은 대원이라고 하는 더 큰 궤도 내의 작은 궤도로 설명된다: 한 행성이 지구를 공전하는 것처럼 원래 궤도를 공전하므로, 그 궤적은 에피트로코이드(epitrochoid)로 알려진 한 곡선과 유사하다. 이것은 지구에서 보았을 때 그 행성이 어떻게 움직이는 것처럼 보이는지 설명할 수 있었다.

- 기원전 2세기 – 에라토스테네스는 지구의 반지름이 대략 6,400km로 결정한다.[34]

- 기원전 2세기 – 히파르코스는 달까지의 거리가 대략 380,000km로 결정하기 위해서 시차를 사용한다.[35] 지구-달 시스템에 대한 히파르코스의 작업은 매우 정확하여 다음 6세기 동안 일식과 월식을 예측할 수 있었다. 또한, 그는 분점의 세차 운동을 발견하고 약 850개 항목의 한 성표를 작성한다.[36]

- 약 기원전 2세기 ~ 기원후 3세기 – 힌두 우주론(Hindu cosmology)에서 마누스므리티(1.67–80)와 푸라나는 시간을 주기적인 것으로 기술하며, 브라흐마는 86억 4천만 년마다 새로운 우주(행성들 및 생명)를 생성한다. 우주는 43억 2천만 년 동안 지속되는 칼파(브라흐마의 낮) 기간 내에 생성, 유지 및 파괴되며, 또한 그 뒤에는 같은 기간 동안 부분적 소멸의 프라라야(밤) 기간이 이어진다. 일부 푸라나(예: 바가바타 푸라나에서는 물질(마하트-타트바(mahat-tattva) 또는 우주의 자궁(Universal Womb))이 622조 8000억 년마다 원시 물질(프라크리티(Prakṛti))과 뿌리 물질(프라다나(pradhana))에서 생성되는 더 큰 시간 주기가 설명되여 있으며, 여기서 브라흐마가 태어난다.[37] 우주의 원소들은 브라흐마에 의해서 생성되고, 사용되며 또한 36,000칼파(낮)와 프랄라야(밤)를 포함하는 311조 4천억년 동안 지속되는 한 마하-칼파(브라흐마의 생애; 그의 360일 해의 100년) 기간 내에 완전히 용해되고, 또한 그 뒤에는 같은 기간 동안 완전한 용해의 한 마하-팔라야 기간이 이어진다.[38][39][40][41] 문서들은 또한 무수한 세계들 또는 우주들에 대해 말한다.[42]

- 2세기 CE – 프톨레마이오스는 태양, 달 및 눈에 보이는 행성이 지구 주위를 도는 지구 중심의 우주를 제안한다. 아폴로니오스의 주전원을 기반으로[43] 그는 이러한 양들을 측정하는 도구들과 함께 천체의 위치들, 궤도 및 위치 방정식들을 계산한다. 프톨레마이오스는 주전원 운동이 태양에 적용되지 않는다고 강조했다. 모형에 대한 그의 주요 기여는 에쿠안트(equant) 점이였다. 그는 플라톤과는 다른 순서(지구에서 바깥쪽으로)로 천구를 재배열했다: 달, 수성, 금성, 태양, 화성, 목성, 토성 및 항성들, 이것들은 한 오랜 점성술 전통과 감소하는 궤도 주기에 따랐다. 1,022개의 별과 기타 천체(주로 히파르코스에 기초함)를 목록화한 그의 저서 《알마게스트》는 17세기까지 천문학에서 관한 가장 권위 있는 문서이며 또한 가장 큰 천문학 목록으로 남았다.[44][45]

중세 시대[편집]

- 기원전 2세기-5세기 – 자이나교 우주론은 로카(loka) 또는 우주를 무한대부터 존재하는 창조되지 않은 한 실체로서, 우주의 모양은 다리를 벌리고 서서 팔을 허리에 얹은 한 사람과 유사하다고 간주한다. 자이나교에 따르면, 이 우주는 위가 넓고 가운데가 좁으며 아래로 갈수록 넓어진다.

- 5세기(또는 그 이전) - 불교 경전들은 동쪽으로 "수십억, 셀 수 없이, 무수히, 끝없이, 비교할 수 없이, 헤아릴 수 없이, 말로 표현할 수 없이, 불가사의하게, 헤아릴 수 없이, 설명할 수 없이 많은 세계"를 말하고, "열 방향의 무한한 세계"들에 대해 말한다. ".[46][47]

- 5세기 – 몇몇 인도 천문학자들은 아리아바타를 포함하여 기초적인 태양 중심 우주를 제안한다. 그는 또한 행성들, 태양, 달 및 별들의 운동에 관한 논문을 쓴다. 아리아바타는 지구의 자전 이론을 제시하고 또한 낮과 밤이 지구의 날마다의 자전으로 인해 발생한다고 설명했다. 그는 또한 천문학적 실험과 관찰을 통해 자신의 개념에 대한 경험적 증거를 제공했다.[48]

- 5세기 – 유대인 탈무드는 설명과 함께 유한 우주(finite universe 이론에 대한 한 논증을 제공한다.

- 5세기 – 마르티아누스 카펠라Martianus Capella는 한 수정된 지구 중심 모형을 설명한는데, 여기서는 지구는 우주의 중심에 있고 또한 달, 태양, 세 개의 행성들 및 별들에 의해 원을 그리며, 한편 수성 및 금성은 태양을 돌며, 모두 항성들의 구체에 둘러써여 있다.[49]

- 6세기 – 존 피로포누스John Philoponus는 시간이 유한한 한 우주를 제안하고 또한 어떤 무한한 우주라는 고대 그리스 개념에 반대한다고 주장한다.

- 7세기 – 쿠란은 21장: 시편 30 – "믿지 않는 자들은 하늘과 땅이 결합된 한 실체라고 생각하지 않았느냐, 그래서 우리가 그것들을 분리시켰다"라고 말한다.

- 9~12세기 – 알 킨디 Al-Kindi(Alkindus), 사디아 가온 Saadia Gaon(Saadia ben Joseph) 및 알가잘리Al-Ghazali(Algazel)는 유한한 과거를 가진 한 우주를 지지하고 이 개념에 대한 두 가지 논리적 주장들을 발전시킨다.

- 12세기 – 파흐르 알딘 알라지 Fakhr al-Din al-Razi는 이슬람 우주론(Islamic Cosmology에 대해 논의하고, 지구 중심 우주에 대한 아리스토텔레스의 사고를 거부하며 쿠란 구절에 대한 주석의 맥락에서, "모든 찬양은 세계들의 주님이신 하느님께 속하고.," 또한 우주에는 "이 세상 너머에 천 개 이상의 세계들"이 있다고 제안한다.[50]

- 12세기 – 로버트 그로스테스트는 우주의 탄생을 한 폭발과 물질의 결정화로 묘사했다. 그는 또한 축을 중심으로 한 지구의 자전과 낮과 밤의 원인과 같은 몇 가지 새로운 아이디어들을 제시했다. 그의 논문 《데 루체(De Luce)》는 물리적 법칙들의 한 단일 세트를 사용해서 하늘과 땅을 설명하려는 최초의 시도이다.[51]

- 14세기 – 유대인 천문학자 레비 벤 게르손Levi ben Gershon(Gersonides)은 고정된 별들의 가장 바깥쪽 구까지의 거리가 159,651,513,380,944 지구 반지름 또는 현대 단위로 약 100,000 광년 이상으로 추정한다.[52]

- 14세기 - 니콜라스 오렘을 비롯한 여러 유럽 수학자들 및 천문학자들이 지구의 회전 이론을 개발한다. 오레메 또한 그의 개념에 대한 논리적 추론, 경험적 증거 및 수학적 증명들을 제공한다.[53][54]

- 15세기 – 니콜라우스 쿠자누스는 그의 저서 《배운 무지에 대하여(On Learned Ignorance)》(1440)에서 지구가 그 축을 중심으로 회전한다고 제안한다.[55] 오레스메처럼 그도 세계들의 복수 가능성에 대해 썼다.[56]

르네상스[편집]

- 1543 – 니콜라우스 코페르니쿠스가 그의 태양 중심 우주(heliocentric universe)를 그의 《천구의 회전에 관하여》에 발표한다.[58]

- 1576 – 토마스 디지스Thomas Digges는 외부 가장자리를 제거하고 가장자리를 한 별들로 가득찬 무제한의 공간으로 대체하여 코페르니쿠스 시스템(Copernican system)을 수정한다.[59]

- 1584 - 조르다노 브루노는 코페르니쿠스 태양계가 우주의 중심이 아니라, 다른 별들의 한 무한한 다수들 중에서, 한 상대적으로 중요하지 않은 항성계이라는 한 비계층적 우주론을 제안한다.[60]

- 1588 – 티코 브라헤가 프톨로마이오스의 고전적인 지구 중심 모형과 코페르니쿠스의 태양 중심 모형의 한 혼합인, 자신만의 티코닉 시스템(Tychonic system)을 발표하는데, 여기서 태양과 달은 우주의 중심에서 지구 주위를 회전하고 또한 모든 다른 행성들은 태양 주위를 회전한다.[61] 소마야지가 설명한 것과 유사한 한 지구-태양 중심 모형이다.

- 1600 – 윌리엄 길버트는 어떤 증거도 제시되지 않은 한 제한적인 고정된 별들의 구(sphere of the fixed stars)에 대한 아이디어를 거부한다.[62]

- 1609 – 갈릴레오 갈릴레이는 한 망원경을 통해 하늘과 별자리들를 조사하고 또한 연구되고 매핑된 "고정된 별(fixed stars)"은 육안으로 닿을 수 없는 거대한 우주의 한 아주 작은 부분에 불과하다는 결론을 내렸다.[63] 1610년에 그는 망원경을 은하수의 희미한 띠로 향하게 했을 때, 그것이 셀 수 없이 많은 하얀 별 모양의 점, 아마도 더 먼 별 자체로 분해되는 것을 발견했다.[64]

- 1610 – 요하네스 케플러는 어두운 밤하늘을 사용하여 한 유한한 우주를 주장한다. 얼마 지나지 않아서, 케플러 자신에 의해서 목성의 위성이 행성들이 태양 주위를 공전하는 것과 같은 방식으로 그 행성 주위를 돈다는 것이 증명되었고, 이렇게 하여케플러의 법칙을 보편적인 것으로 만들었다.[65]

계몽시대에서 빅토리아 시대까지[편집]

- 1672 – 장 리에리히Jean Richer와 조반니 도메니코 카시니는 천문 단위인 지구-태양 거리를 약 1억 3837만 km로 측정한다.[66] 이는 나중에 다른 사람들에 의해 현재 값인 149,597,870km까지 개선될 것이다.

- 1675 – 올레 뢰머는 목성의 위성의 궤도 역학을 사용하여 빛의 속도가 약 227,000km/s라고 추정한다.[67]

- 1687 – 아이작 뉴턴의 법칙은 우주 전체의 대규모 운동을 설명하다. 만유인력은 별들이 단순히 고정되거나 정지해 있을 수 없다는 것을 시사했는데, 이는 그 중력적 당김이 "상호 인력"을 유발하고, 따라서 서로 관련하여 움직이게 하기 때문이다.[68]

- 1704 – 존 로크가 영어로 "태양계"(Solar System)라는 용어를 영어로 입력하고, 태양, 행성들, 혜성들 전체를 지칭할 때 이 용어를 사용하곤 했다.[69] 그때까지 행성들은 다른 세계이고, 별들은 다른 먼 태양이라는 것이 의심할 여지 없이 확립되었으므로, 그래서 전체 태양계는 실제로 엄청나게 큰 우주의 한 작은 부분에 불과하며, 또한 분명히 별개인 어떤 것이다.

- 1718 – 에드먼드 핼리가 별의 고유운동을 발견하여 "고정된 별(fixed stars)"의 개념을 없앤다.[70]

- 1720 – 에드먼드 핼리가 올베르스의 역설의 초기 형태를 제시한다.

- 1729 - 제임스 브래들리가 태양 주위를 도는 지구의 운동을 증명한 광행차를 발견하고,[71] 또한 빛의 속도를 실제 값인 약 300,000km/s에 더 가깝게 계산하는 더욱 정확한 방법을 제공한다.

- 1744 – 장 필리프 드 체소Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux는 올베르스의 역설의 초기 형태를 제시한다.

- 1755 - 임마누엘 칸트는 성운이 실제로 은하수와 분리되어 있고, 독립적이며 외부에 있는 은하라고 주장한다. 그는 이것을 섬 우주들이라고 부른다.

- 1781 – 샤를 메시에와 그의 조수인 피에르 메셍은 일반 태양계의 혜성과 혼동하지 않기 위해 지구의 북반구에서 쉽게 관찰할 수 있는 가장 눈에 띄는 심원천체인 110개의 성운들과 성단들에 대한 최초의 카탈로그를 발간한다.[72]

- 1785 – 윌리엄 허셜은 지구의 태양이 우주의 중심 또는 그 근처에 있다는 태양 중심 우주 모형을 제안하는데, 그 당시에는 은하수 은하만 있다고 추정되었다.[73]

- 1791 – 이래즈머스 다윈은 그의 시 《식물의 경제(The Economy of Vegetation)》에서 주기적인 팽창하고 및 수축하는 우주에 대한 첫 번째 기술을 쓴다.

- 1796 – 피에르 라플라스가 가스와 먼지의 회전하는 성운으로부터 태양계 형성에 대한 성운 가설을 다시 언급한다.[74]

- 1826 - 하인리히 빌헬름 올베르스가 올베르스의 역설을 제시한다.

- 1832–1838 – 100년이 넘는 시도가 실패한 끝에 토마스 헨더슨Thomas Henderson,[75] 프리드리히 베셀[76]과 오토 스트루브Otto Struve는 근처에 있는 몇 개의 별의 시차를 측정한다; 이것은 태양계 외부의 어떤 거리에 대한 최초의 측정이다.

- 1842 – 크리스티안 도플러는 소리에서 발견되는 아날로그 효과를 기반으로 적색편이 및 청색편이 효과를 제안한다.[77] 이폴리트 피조는 1848년에 전자기파에서 동일한 현상을 독립적으로 발견했다.[78]

- 1848 – 에드거 앨런 포는 또한 우주의 팽창과 붕괴를 암시하는 한 에세이인 《유레카: 산문시(Eureka: A Prose Poem)》에서 올베르스의 역설에 대한 최초의 올바른 해결책을 제시한다.

- 1860년대 – 윌리엄 허긴스가 천문 분광학을 개발한다; 그는 오리온 성운이 대부분 가스로 구성되어 있는 반면, 안드로메다 성운(나중에 안드로메다 은하로 불림)은 아마도 별들이 지배되고 있는 것을 보여준다.

- 1862 – 태양의 분광학적 특징을 분석하고 또한 그것을 다른 별들의 특징과 비교함으로써, 안젤로 세키 신부는 태양 자체도 또한 별이라는 것을 임을 밝혀낸다.[79]

- 1887 – (가정된) 고정 에테르를 통해 지구의 상대 운동을 측정하기 위한 마이컬슨-몰리 실험은 결과를 얻지 못했다. 이것은 아리스토텔레스로 거슬러 올라가는 수세기에 걸친 에테르에 대한 아이디어와 또한 그것과 함께하는 현대의 모든 에테르 이론에 종지부를 찍었다.[80]

- 1897 - J. J. 톰슨은 전자를 음극선의 구성 입자들로 식별하여, 현대적 물질의 원자 모형으로 이끈다.[81]

- 1897 - 제1대 켈빈 남작 윌리엄 톰슨은 열복사율과 중력적 수축력에 기반으로, 당시 알려진 것 이상의 에너지원이 발견되지 않는 한 태양의 나이가 2천만년을 넘지 않는다고 주장한다.[82]

1901-1950[편집]

- 1904 – 어니스트 러더퍼드는, 켈빈이 참석한 강의에서, 방사성 붕괴가 열을 방출하여 켈빈이 제안한 미지의 에너지원을 제공하고, 궁극적으로 암석의 방사능 연대 측정으로 이어져 태양계 천체 즉 태양과 모든 별들에 대해 수십억 년의 나이를 밝혀준다고 주장한다.[83]

- 1905 – 알베르트 아인슈타인은 특수 상대성이론을 발표하여, 시공간이 분리된 연속체들이 아니라는 것을 사실로 상정하고, 또한 질량과 에너지가 서로 교환 가능하다는 것을 증명한다.

- 1912 – 헨리에타 레빗이 세페이드 변광성의 주기-광도 법칙을 발견하는데, 이것은 다른 은하까지의 거리를 측정하는 한 결정적인 단계가 된다.

- 1913 – 닐스 보어는 스펙트럼 선(spectral line)을 설명하는 원자의 보어 모형을 발표하고, 또한 물질의 양자 역학 거동을 결정적으로 확립했다.[84]

- 1915 - 로버트 이네스Robert Innes는 태양 다음으로 지구에서 가장 가까운 별인 프록시마 센타우리를 발견한다.[85]

- 1915 – 알베르트 아인슈타인은 일반 상대성이론을 발표하는데, 이것은 한 에너지 밀도가 시공간을 휘게 만든다는 것을 보여주다.

- 1917 – 빌럼 더시터르는 우주상수가 있는 한 등방성 정적 우주론을 도출하고, 이와 더불어 더시터르 우주(de Sitter universe)라고 용어회 된 우주상수가 있는 한 빈 팽창 우주론을 도출한다.

- 1918 – 구상성단에 대한 할로 섀플리의 연구는 우주론의 태양중심설이 틀렸다는 것을 보여주었고, 은하중심설(galactocentrism)은 태양중심설을 대체하여 우주론의 지배적인 모형이 되었다.[73]

- 1919 – 아서 스탠리 에딩턴은 일식을 사용하여 알베르트 아인슈타인의 일반 상대성이론을 성공적으로 테스트한다.[86]

- 1920 – 나선 성운까지의 거리에 대한 섀플리-커티스 논쟁이 스미소니언에서 열린다.

- 1921 – 국립 연구위원회(National Research Council, NRC)에서 섀플리-커티스 논쟁의 공식 기록을 발표했다. 은하는 마침내 우리 은하 너머의 천체들로, 우리 은하는 한 진정한 은하로 인식된다.[87]

- 1922 – 베스토 슬라이퍼가 나선 성운의 체계적인 적색편이에 대한 연구 결과들을 요약한다.

- 1922 – 알렉산드르 프리드만은 공간의 한 일반적인 팽창을 암시하는 아인슈타인 방정식에 대한 한 해를 찾아낸다.

- 1923 - 에드윈 허블이 근처의 나선 성운(은하) 몇 개, 안드로메다 은하(M31), 삼각형자리 은하(M33) 및 NGC 6822까지의 거리들을 측정한다. 그 거리들은 그것들을 우리 은하 바깥쪽에 위치시키며, 또한 더 희미한 은하들이 훨씬 더 멀고, 또한 우주가 수천 개의 은하로 구성되어 있다는 것을 의미한다.

- 1924 - 루이 드 브로이는 적당히 가속된 전자들이 한 관련 파동을 보여야 한다고 주장한다.[88] 이것은 나중에 1927년 데이비슨-거머 실험에 의해 확인되었다.[89]

- 1927 – 조르주 르메트르는 아인슈타인 방정식에 의해 지배되는 한 팽창하는 우주의 생성 사건에 대해 논의한다. 아인슈타인 방정식에 대한 해들로부터, 그는 거리-적색편이 관계를 예측한다.

- 1928 - 폴 디랙은 전자들에 대한 슈뢰딩거 파동 방정식의 상대론적 버전이 반전자들, 그리고 따라서 반물질들의 가능성을 예측한다는 것을 깨닫는다.[90] 이것은 1932년 칼 D. 앤더슨에 의해서 확인되었다.[91]

- 1928 - 하워드 P. 로버트슨Howard P. Robertson은 동일한 은하들의 밝기 측정과 결합된 베스토 슬라이퍼의 적색편이 측정들이 어떤 적색편이-거리 관계를 나타낸다고 간략하게 언급힌다.

- 1929 – 에드윈 허블이 선형 적색편이-거리 관계를 입증하고 또한 이렇게 하여 우주의 팽창을 보여준다.

- 1932 – 칼 구스 잰스키는 우주 공간에서 오는 수신된 무선 신호들을 태양계 외부로서 인식하는데, 이것들은 주로 궁수자리로부터 온다.[93] 그것들은 우리 은하의 중심에 대한 최초의 증거이자, 또한 전파천문학의 분야을 확립한 최초의 경험들이다.

- 1933 - 에드워드 밀른Edward Milne이 우주론 원리를 명명하고 공식화한다.

- 1933 - 프리츠 츠비키는 머리털자리 은하단에 많은 양의 암흑물질이 포함되어 있음을 보여준다. 이 결과는 현대 측정과 일치하는데, 그러나 일반적으로 1970년대까지 무시되었다.

- 1934 – 조르주 르메트르는 한 비정상적인 완전 유체 상태 방정식을 가진 한 진공 에너지(vacuum energy)로서 우주상수를 해석한다.

- 1938 – 한스 베테가 별에 파워를 공급하는 두 가지 주요 에너지 생성 핵반응들의 세부 사항들을 계산한다.[94][95]

- 1938 – 폴 디랙은 중력 상수가 시간이 지남에 따라 천천히 감소하기 때문에 작을 수 있다는 큰 수 가설(large numbers hypothesis)을 제안한다.

- 1948 – 랠프 앨퍼, 한스 베테 그리고 조지 가모프는 한 빠르게 팽창하고 냉각되는 우주에서 원소 합성을 조사하고 또한 원소들이 빠른 중성자 포획에 의해 생성되었다는 알파 베타 감마 이론을 제안한다.

- 1948 – 헤르만 본디Hermann Bondi, 토마스 골드Thomas Gold, 그리고 프레드 호일은 완벽한 우주론 원리에 기초한 정상우주론들을 제안한다.

- 1948 – 조지 가모프는 한 팽창하는 우주에서 원시 복사의 거동을 고려하여 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사의 존재를 예측한다.

- 1950 – 프레드 호일은 "빅뱅(대폭발)"이라는 용어를 만들었는데, 그것은 조롱하는 것이 아니었다; 그것은 단지 정상우주론과의 차이점을 강조하기 위한 한 인상적인 이미지였을 뿐이라고 말한다.

1951-2000[편집]

- 1961 - 로버트 헨리 딕는 중력적 힘이 작을 때만 탄소 기반의 생명이 생겨날 수 있으며, 이것운 불타는 별들이 존재할 때이기 때문이다라고 주장한다; 약한 인류 원리의 첫 번째 사용.

- 1963 – 마르턴 스밋이 최초의 퀘이사를 발견한다; 이것들은 곧 상당한 적색 편이들로 되돌아가는 한 우주 탐사를 제공한다.

- 1965 – 한네스 알벤은 중입자 비대칭을 설명하기 위해 지금은 할인된 앰비플라즈마(ambiplasma) 개념을 제안하고 또한 한 무한한 우주에 대한 아이디어를 지지한다.

- 1965 – 마틴 리스Martin Rees와 데니스 시아마Dennis Sciama는 퀘이사 소스 수 데이터를 분석하여 퀘이사 밀도가 적색편이와 함께 증가한다는 사실을 발견한다.

- 1965 – 벨 연구소의 천문학자들인 아노 펜지어스와 로버트 윌슨은 2.7K 마이크로파 배경 복사를 발견하였는데, 이것은 그들에게 1978년 노벨 물리학상을 받개 해준다. 로버트 딕, 제임스 피블스, 피터 롤Peter Roll 그리고 데이비드 토드 윌킨슨은 이것을 대폭발(빅뱅)으로부터의 한 유물로 해석한다.

- 1966 - 스티븐 호킹과 조지 엘리스는 어떤 그럴듯한 일반 상대론적 우주론은 특이점이 있다는 것을 보여준다.

- 1966 – 제임스 피블스는 뜨거운 대폭발(빅뱅)이 정확한 헬륨 존재비를 예측한다는 것을 보여준다.

- 1967 – 안드레이 사하로프는 우주에서 중입자 생성, 중입자-반중입자 비대칭 대한 요구 사항을 제시한다.

- 1967 - 존 바콜John Bahcall, 왈 사르겐트Wal Sargent 그리고 마르턴 스밋은 3C191에서 스펙트럼 선의 미세 구조 분할을 측정하여 미세 구조 상수가 시간에 따라 크게 변하지 않음을 보여준다.

- 1967 - 로버트 와그너Robert Wagner, 윌리엄 파울러William Fowler 그리고 프레드 호일은 뜨거운 대폭발(빅뱅)이 정확한 중수소와 리튬의 존재비를 예측한다는 것을 보여준다.

- 1968 – 브랜던 카터는 아마도 자연의 기본 상수들이 생명의 출현을 허용하는 한 제한된 범위 내에 있어야 한다고 추측한다; 강한 인간 원리의 첫 번째 사용.

- 1969 – 찰스 미스너가 공식적으로 대폭발(빅뱅) 지평선 문제를 발표한다.

- 1969 – 로버트 딕이 대폭발(빅뱅) 편평도 문제를 공식적으로 발표한다.

- 1970 - 베라 루빈과 켄트 포드Kent Ford가 큰 반경에서 나선은하 회전 곡선을 측정하여, 상당한 양의 암흑물질에 대한 증거를 보여눈다+.

- 1973 – 에드워드 트라이온Edward Tryon은 우주가 양의 질량 에너지가 음의 중력 포텐셜 에너지에 의해서 균형을 이루는 어떤 거대규모 양자 역학적 진공 요동일 수 있다고 제안한다.

- 1976 – 알렉산더 슐랴크터Alexander Shlyakhter는 가봉에 있는 오클로(Oklo) 선사 시대 자연 핵분열 원자로(natural nuclear fission reactor)의 사마륨 비율을 사용하여 일부 물리 법칙들이 20억 년 이상 변하지 않았음을 보여준다.

- 1977 – 게리 스타이그먼Gary Steigman, 데이비드 슈람David Schramm 그리고 제임스 건은 원시 헬륨의 존재비와 중성미자 수 사이의 관계를 조사하고 최대 5개의 경입자 계열이 존재할 수 있다고 주장한다.

- 1980 – 앨런 구스와 알렉세이 스타로빈스키는 지평선 및 편평도 문제에 대한 가능한 한 해결책으로 급팽창 이론적 대폭발(빅뱅) 우주를 독립적으로 제안한다.

- 1981 – 뱌체슬라프 무하노프Viatcheslav Mukhanov와 G. 치비소프G. Chibisov는 양자 요동이 한 급팽창적 우주에서 한 거대규모 구조로 이어질 수 있다고 제안한다.

- 1982 – 최초의 CfA 은하 적색편이 조사가 완료된다.

- 1982 – 제임스 피블스, J. 리처드 본드J. Richard Bond 그리고 조지 블루멘탈George Blumenthal을 포함한 여러 그룹들은 우주가 차가운 암흑물질에 의해 지배된다고 제안한다.

- 1983–1987 – 우주 구조 형성에 대한 최초의 대규모 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션은 데이비스, 에프스타시우Davis, Efstathiou, 프렌크Frenk 그리고 화이트White에 의해 실행된다. 그 결과들은 차가운 암흑물질은 관측치와 합리적으로 일치하지만, 뜨거운 암흑물질은 그렇지 않다는 것을 보여준다.

- 1988 – CfA2 장성이 CfA2 적색편이 조사에서 발견된다.

- 1988 – 은하계 거대규모 흐름의 측정은 거대 인력체에 대한 증거를 제공한다.

- 1990 – 허블 우주 망원경이 발사된다.[96] 주로 심원천체를 대상으로 한다.

- 1990 – NASA의 COBE 임무의 예비 결과는 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사가 105분의 일의 놀라운 정밀도로 한 흑체 스펙트럼을 가지고 있음을 확인하여, 정상우주론 애호가들에 의한 배경에 대해 제안한 어떤 통합된 별빛 모형의 가능성을 제거한다.

- 1992 – 추가 COBE 측정은 우주 마이크로파 배경의 매우 작은 비등방성을 발견하여, 우주가 현재 크기의 약 1/1100이고 380,000년이 되었을 때 거대규모 구조의 씨앗들에 대한 한 "아기 사진"을 제공한다.

- 1992 – 펄사 PSR B1257+12 주변에서 태양계 밖에서 최초의 행성계가 발견된다.[97]

- 1995 – 태양과 같은 별 주위의 첫 번째 행성이 발견되었는데, 펄사 페가수스자리 51 주위를 공전한다.[98]

- 1996 – 최초의 허블 딥 필드가 공개되어서, 우주가 현재 나이의 약 1/3일 때 매우 먼 은하의 어떤 명확한 뷰를 제공한다.

- 1998 – 우주의 생애 동안 변화하는 미세 구조 상수에 대한 논란의 여지가 있는 증거가 처음으로 발표된다.

- 1998 – 초신성 우주론 프로젝트(Supernova Cosmology Project) 및 하이-Z 초신성 탐색팀(High-Z Supernova Search Team)은 Ia형 초신성까지의 거리를 기반으로 우주 가속도를 발견하여 0이 아닌 우주 상수에 대한 최초의 직접적인 증거를 제공한다.

- 1999 – COBE보다 더 정밀한 해상도로 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사의 측정(특히 BOOMERanG 실험에 의해, 마우스코프Mauskopf 외, 1999, 멜치오리Melchiorri 외, 1999, 드 베르나르디스de Bernardis 외, 2000 참조) 우주 구조 형성의 표준 모형에서 예상되는 비등방성 각도 스펙트럼의 진동(첫 번째 음향 피크)에 대한 증거를 제공한다. 이 피크의 각도 위치는 우주의 기하학이 평평에 가깝다는 것을 나타낸다.

2001-현재[편집]

- 2001 – 호주/영국 팀의 2dF 은하 적색편이 탐사(2dF)는 물질 밀도가 임계 밀도의 25%에 가깝다는 강력한 증거를 제시했다. 평평한 우주에 대한 CMB 결과와 함께 이것은 우주 상수 또는 유사한 암흑 에너지에 대한 독립적인 증거를 제공한다.

- 2002 – 칠레의 우주 배경 이미저(Cosmic Background Imager(CBI)는 4 분각의 최고 각도 해상도로 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사 이미지들을 획득했다. 또한 1 ~ 3000까지 이전에 다루지 않았던 고해상도에서 비등방성 스펙트럼을 얻었다. 아직 완전히 설명되지 않은 고해상도(1 > 2500)에서 약간의 파워 초과, 소위 "CBI-초과"를 발견했다.

- 2003 – NASA의 윌킨슨 마이크로파 비등방성 탐색기(WMAP)는 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사의 전체 하늘 상세 사진을 얻었다. 그 이미지들은 우주의 나이가 137억 년(1% 오차 이내)이며, 또한 ΛCDM 모형 및 급팽창에 의해서 예측된 밀도 변동들과 매우 일치하는 것으로 해석될 수 있다.

- 2003 – 슬론 장성이 발견된다.

- 2004 – DASI(Degree Angular Scale Interferometer)는 처음으로 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사의 E-모드 편광 스펙트럼을 얻었다.

- 2004 – 보이저 1호는 태양계의 태양권덮개 내에서 얻은 최초의 데이터를 다시 보낸다.[99]

- 2005 – 슬론 디지털 전천탐사(SDSS) 및 2dF 적색편이 조사에서 모두 차가운 암흑물질 모형의 한 핵심 예측인 은하 분포에서 중입자 음향 진동 특징을 감지했다.

- 2006 – 이전 분석을 확인하고 몇 가지 사항을 수정하고 편광 데이터를 포함하는 3개년 WMAP 결과가 발표된다.

- 2009–2013 – 유럽 우주국(ESA)에서 운영하는 우주 관측소인 플랑크 위성은 증가된 감도 및 작은 각도 해상도로 우주 마이크로파 배경 복사의 비등방성을 매핑했다.

- 2006–2011 – WMAP의 개선된 측정, 새로운 초신성 조사 ESSENCE 및 SNLS, 슬론 디지털 전천탐사 및 WiggleZ의 중입자 음향 진동은 표준 ΛCDM 모형과 계속 일치하고 있다.

- 2014 – BICEP2 협력의 천체물리학자들은 B-모드 파워 스펙트럼(power spectrum)에서 급팽창 중력파들의 감지를 발표했다. 만일 확인된다면, 급팽창 이론에 대한 명확한 실험적 증거를 제공할 것이다.[100][101][102][103][104][105] 그렇지만, 6월에 우주 급팽창 발견을 확인하는 데 대한 낮은 신뢰도가 보고되었다.[104][106][107]

- 2016 – 레이저 간섭계 중력파 관측소 과학 협업(LIGO Scientific Collaboration)과 Virgo 협업은 중력파가 두 개의 레이저 간섭계 중력파 관측소(LIGO) 검출기들에 의해 중력파들이 직접 감지되었다고 발표한다. 이 파형은 내부 나선에서 방출되는 중력파와 약 36 및 29 태양질량의 한 쌍의 블랙홀의 병합 후 단일 후속 블랙홀의 "링다운(ringdown)"에 대한 일반 상대성이론의 예측과 일치했다.[108][109][110] 두 번째 탐지(GW151226)는 GW150914가 한 요행이 아니라는 것을 확인했으며, 따라서 천체물리학에서 완전히 새로운 가지인 중력파 천문학(gravitational-wave astronomy이 열린다.[111][112]

- 2019 – 사건 지평선 망원경(Event Horizon Telescope) 협업이 M87 은하의 중심에 있는 블랙홀의 이미지를 발표한다.[113] 천문학자들이 블랙홀의 이미지를 포착한 것은 이번이 처음으로, 이는 다시 한 번 블랙홀의 존재를 증명하고 또한 아인슈타인의 일반 상대성이론을 검증하는 데 도움이 된다.[114] 이것은 매우 긴 기준선 간섭계를 사용하여 수행되었다.[115]

- 2020 – 제네바 대학의 물리학자 루카스 롬브리저Lucas Lombriser는 나머지 우주 밀도의 절반인 직경 2억 5천만 광년인 한 주변 광대한 "거품"(vast "bubble" 개념을 제안함으로써 허블 상수의 두 가지 상당히 다른 결정을 조화시키는 한 가능성 있는 방법을 제시한다.[116][117]

- 2020 – 과학자들은 우주가 더 이상 모든 방향으로 동일한 속도로 팽창하지 않으며 따라서 널리 받아들여지는 등방성 가설이 틀릴 수 있다는 연구 결과를 발표한다. 이전 연구들에이 이미 이것을 제시했지만, 그 연구는 X선으로 은하단들을 조사한 최초의 연구이며 또한, 노르베르트 샤르텔Norbert Schartel에 따르면, 훨씬 더 큰 의미가 있다. 그 연구는 정규화 매개변수 A 또는 허블 상수 H0의 편차들 - 이것들은 다른 사람들에 의해 "우주론의 위기"를 나타내는 것으로 일찌기 설명된 바 있음 -의 한 일관되고 또한 강한 방향적 거동을 발견했다. 잠재적인 우주론적 의미를 넘어, 그것은 은하단들의 속성들 및 스케일링 관계들에서 완벽한 등방성을 가정하는 연구들은 강하게 편향된 결과를 낳을 수 있음을 보여준다.[118][119][120][121][122]

- 2020 – 과학자들은 ULAS J1120+0641을 통해 하전 입자 사이의 전자기를 측정하는 데 사용되는 한 기본 물리 상수인 미세 구조 상수의 네 가지 측정에서 한 공간적 변화로 보이는 2011–2014 측정치를 확인하여 보고하는데, 이는 우주의 거주 가능성의 현현에 대한 이론들에 영향을 미칠 수있는 우주의 다양한 자연 상수들과 더불어 방향성이 있을 수 있으며 또한 널리 받아 들여지는 일정한 자연 법칙들의 이론 및 한 등방성 우주에 기반을 둔 우주론의 표준 모형과 상충 될 수 있음을 나타낸다.[123][124][125][126]

- 2021 – 제임스 웹 우주 망원경이 발사된다.[127]

- 2023 - 천체 물리학자들은 최신 제임스 웹 우주 망원경 연구를 기반으로 우주론의 표준 모형의 형태인 우주에 대한 전반적인 현재 견해에 의문을 제기했다.[128]

같이 보기[편집]

믈리 우주론[편집]

가설의 역사적 발전[편집]

- 태양계 천문학 연표(Timeline of Solar System astronomy)

- 은하, 은하단, 대규모 구조에 대한 지식 연표(Timeline of knowledge about galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and large-scale structure)

- 우주 마이크로파 배경 천문학 연표

- 태양계의 역사적 모형(Historical models of the Solar System)

- 고정된 별(Fixed stars)

신앙 체계[편집]

- 불교의 우주론

- 자이나교 우주론(Jain cosmology)

- 자이나교와 비창조론(Jainism and non-creationism)

- 힌두 우주론(Hindu cosmology)

- 마야 신화(Maya mythology)

기타[편집]

각주[편집]

- ↑ Horowitz (1998), p. xii>

- ↑ This is a matter of debate: Cornford, F. M. (1934). "Innumerable Worlds in Presocratic Philosophy". The Classical Quarterly. 28 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1017/S0009838800009897. Curd, Patricia; Graham, Daniel W. (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–41. Gregory, Andrew (2016). "7 Anaximander: One Cosmos or Many?". Anaximander: A Re-assessment. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 121–142.

- ↑ Siegfried, Tom. "Long Live the Multiverse!". Scientific American. Siegfried, Tom (2019). "Aristotle versus the Atomists". The number of the heavens : a history of the multiverse and the quest to understand the cosmos Archived 2023년 5월 26일 - 웨이백 머신. Harvard.

- ↑ "크기가 다른 수많은 세계가 있다. 어떤 것에는 태양도 달도 없고, 다른 것들은 우리보다 크며, 다른 것들은 하나 이상이다. 이 세계는 불규칙한 거리에 있으며 한 방향으로 더 많고 다른 방향으로는 더 적다. 일부는 번성하고 다른 일부는 쇠퇴한다. 여기에서 그들은 존재하고, 거기에서 죽고, 서로 충돌하여 파괴된다. 일부 세계에는 동식물이 없으며 물도 없다." Guthrie, W. K. C.; Guthrie, William Keith Chambers (1962). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 2, The Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 404–06. Vamvacas, Constantine J. (2009). The Founders of Western Thought – The Presocratics: A diachronic parallelism between Presocratic Thought and Philosophy and the Natural Sciences. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 219–20.

- ↑ "Ancient Greek Astronomy and Cosmology | Modeling the Cosmos | Articles and Essays | Finding Our Place in the Cosmos: From Galileo to Sagan and Beyond | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Washington, DC.

- ↑ Blakemore, Erin. "Christopher Columbus Never Set Out to Prove the Earth was Round". History.com.

- ↑ Aristotle, On the Heavens, ii, 13

- ↑ "A column of stone", Aetius reports in De Fide (III, 7, 1), or "similar to a pillar-shaped stone", pseudo-Plutarch (III, 10).

- ↑ Sider, D. (1973). "Anaxagoras on the Size of the Sun". Classical Philology. 68 (2): 128–129. doi:10.1086/365951.

- ↑ In Refutation, it is reported that the circle of the Sun is twenty-seven times bigger than the Moon.

- ↑ Aetius, De Fide (II, 15, 6)

- ↑ Most of Anaximander's model of the Universe comes from pseudo-Plutarch (II, 20–28): ""[태양]은 지구보다 28배 큰 원이며 윤곽은 불이 가득한 전차 바퀴와 비슷하며 특정 위치에 입이 나타나고 피리의 구멍처럼, 이를 통해 불을 내뿜는다. [...] 태양은 지구와 같지만 태양이 숨 쉬고 떠다니는 원은 지구 전체의 27배이다. [...] [월식]은 불의 열기가 나오는 입이 닫히는 때이다. [...] [달]은 전체 지구보다 19배 큰 원이며, 모두 태양처럼 불로 가득 차 있다."

- ↑ Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). "Others: Parmenides" . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

- ↑ Thurston, Hugh (1994). Early astronomy. New York: Springer-Verlag New York. p. 111.

- ↑ Dreyer, John Louis Emil (1906). History of the planetary systems from Thales to Kepler. p. 42. "10이라는 숫자를 완성하기 위해 필롤라오스는 안티크톤 또는 반대쪽 지구를 만들었다. 이 열 번째 행성은 우리와 중앙 불 사이에 있고 항상 지구와 보조를 맞추기 때문에 우리에게는 항상 보이지 않는다."

- ↑ Pedersen, Olaf (1993). 그가 영혼을 만든 성분들과 그가 만든 방식은 다음과 같다: 나눌 수 없고 항상 변하지 않는 존재와 나눌 수 있고 육체적 영역에서 생겨나는 존재 사이에, 그는 다른 두 존재에서 파생된, 한 제삼의 존재의 중간 형태를 혼합했다. 유사하게, 그는 나눌 수 없는 것과 나눌 수 있는 육체적 대응물들 사이에서, 동일과 상이의 한 혼합물을 만들었다. 그리고 그는 세 가지 혼합물들을 가져다가 또한 그것들을 함께 섞어 한 균일한 혼합물을 만들었고, 혼합하기 어려운 다름을 같음과 일치하도록 만들었다. 이제 그는 이 두 가지를 존재와 혼합하여 세 가지로부터 한 단일 혼합물을 만들었을 때, 그는 그 전체 혼합물을 자신의 작업에 필요한만큼의 부분들로 다시 나누었고, 각 부분은 동일, 상이 및 존재의 한 혼합물로 남아있었다." (35a-b), translation Donald J. Zeyl

- ↑ "그가 영혼을 만든 구성 요소와 그가 만든 방식은 다음과 같다: 나눌 수 없고 항상 변하지 않는 존재와 나눌 수 있고 육체적 영역에서 생겨나는 존재 사이에, 그는 다른 두 존재에서 파생된 제3의 중간 형태를 혼합했다. 마찬가지로, 그는 나눌 수 없는 것과 나눌 수 있는 육체적 존재 사이에 같은 것과 다른 것을 혼합하여 만들었다. 그리고 그는 세 가지 혼합물을 가져다가 함께 섞어 균일한 혼합물을 만들어 혼합하기 어려운 다른 것을 같은 것과 일치하도록 강요했다. 이제 그는 이 두 가지를 존재와 혼합하고 세 가지에서 하나의 혼합물을 만들었을 때, 그는 전체 혼합물을 자신의 작업에 필요한만큼의 부분으로 다시 나누었고, 각 부분은 동일, 차이, 존재의 혼합물로 남아있었다." (35a-b), Donald J. Zeyl도널드 J. 자일 번역

- ↑ Plato, Timaeus, 36c

- ↑ Plato, Timaeus, 36d

- ↑ Plato, Timaeus, 39d

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (2019). "heliocentrism | Definition, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Yavetz, Ido (February 1998). "On the Homocentric Spheres of Eudoxus". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 52 (3): 222–225. Bibcode:1998AHES...52..222Y.

- ↑ Crowe, Michael (2001). Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution. Mineola, NY: Dover. p. 23.

- ↑ De caelo, 297b31–298a10

- ↑ Easterling, H (1961). "Homocentric Spheres in De Caelo". Phronesis. 6 (2): 138–141. doi:10.1163/156852861x00161.

- ↑ Thurston, Hugh (1994). Early astronomy. New York: Springer-Verlag New York. p. 118.

- ↑ Sorabji, Richard (2005). The Philosophy of the Commentators, 200–600 AD: Physics. Cornell University Press. p. 175.

- ↑ Aristotle; Forster, E. S. (Edward Seymour); Dobson, J. F. (John Frederic) (1914). De Mundo. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 2.

- ↑ Simplicius (2003). "Physics 2". On Aristotle's. Translated by Fleet, Barries. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 48.

- ↑ Eastwood, Bruce (1992). "Heraclides and Heliocentrism: Texts, Diagrams, and Interpretations". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 23 (4): 253. Bibcode:1992JHA....23..233E.

- ↑ D., J. L. E. (July 1913). "Aristarchus of Samos: The Ancient Copernicus". Nature. 91 (2281): 499–500. doi:10.1038/091499a0.

- ↑ 32] "Aristarchus of Samos (310-230 BC) | High Altitude Observatory"[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)]. www2.hao.ucar.edu.

- ↑ Carrol, Bradley and Ostlie, Dale, An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics, Second Edition, Addison-Wesley, San Francisco, 2007. pp. 4.

- ↑ Russo, Lucio (2004). The forgotten revolution : how science was born in 300 BC and why it had to be reborn. Berlin: Springer. p. 68.

- ↑ G. J. Toomer, "Hipparchus on the distances of the sun and moon," Archive for History of Exact Sciences 14 (1974), 126–142.

- ↑ Alexander Jones "Ptolemy in Perspective: Use and Criticism of his Work from Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century, Springer, 2010, p.36.

- ↑ "Mahattattva, Mahat-tattva: 5 definitions". Wisdom Library. February 10, 2021. "Mahattattva (महत्तत्त्व) or simply Mahat refers to a primordial principle of the nature of both pradhāna and puruṣa, according to the 10th century Saurapurāṇa: one of the various Upapurāṇas depicting Śaivism.—[...] From the disturbed prakṛti and the puruṣa sprang up the seed of mahat, which is of the nature of both pradhāna and puruṣa. The mahattattva is then covered by the pradhāna and being so covered it differentiates itself as the sāttvika, rājasa and tāmasa-mahat. The pradhāna covers the mahat just as a seed is covered by the skin. Being so covered there spring from the three fold mahat the threefold ahaṃkāra called vaikārika, taijasa and bhūtādi or tāmasa."(마하트바는 10세기 사우라푸라사에 따르면 프라도나와 푸루자의 본성에 대한 원초적인 원리를 가리킨다.-[...] 동요된 프라키티와 푸루차에서 프라다나와 푸루차의 본질인 마하트의 씨앗이 생겨났다. 마하트바는 프라다나에 의해 덮여 있고, 그렇게 덮여 있는 것은 사트비카, 라자사, 타마사마하트와 구별된다. 마치 씨앗이 껍질로 덮여 있는 것처럼 프라다나는 마하트를 덮는다. 거기에 이렇게 덮여 있는 것은 바이카리카, 타이자사, 부타디 또는 타마사라고 불리는 세 개의 접힌 마하트에서 비롯된다.")

- ↑ Gupta, S. V. (2010). "Ch. 1.2.4 Time Measurements". In Hull, Robert; Osgood, Richard M. Jr.; Parisi, Jurgen; Warlimont, Hans (eds.). Units of Measurement: Past, Present and Future. International System of Units. Springer Series in Materials Science: 122. Springer. pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Penprase, Bryan E. (2017). The Power of Stars (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 182.

- ↑ Johnson, W.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. p. 165.

- ↑ Fernandez, Elizabeth. "The Multiverse And Eastern Philosophy". Forbes.

- ↑ Zimmer, Heinrich Robert (2018). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton University Press. Penprase, Bryan E. (2017). The Power of Stars. Springer. p. 137. Campbell, Joseph (2015). Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, Eranos 3: Man and Time. Princeton University Press. p. 176. Henderson, Joseph Lewis; Oakes, Maud (1990). The Wisdom of the Serpent: The Myths of Death, Rebirth, and Resurrection. Princeton University Press. p. 86.

- ↑ North, John (1995). The Norton History of Astronomy and Cosmology. New York: W.W.Norton & Company, Inc. p. 115.

- ↑ jones, prudence (2011-01-01), Akyeampong, Emmanuel K; Gates, Henry Louis (eds.), "Ptolemy", Dictionary of African Biography, Oxford University Press,

- ↑ Swerdlow, N. M. (February 2021). "The Almagest in the Manner of Euclid". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 52 (1): 104–107.

- ↑ Jackson, Roger; Makransky, John (2013). Buddhist Theology: Critical Reflections by Contemporary Buddhist Scholars. Routledge. p. 118.

- ↑ Reat, N. Ross; Perry, Edmund F. (1991). A World Theology: The Central Spiritual Reality of Humankind. Cambridge University Press. p. 112.

- ↑ India, Digital Branding Learners (2019-01-01). "Aryabhatta and the great Indian Mathematicians". Learners India.

- ↑ Bruce S. Eastwood, Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance (Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 238-9.

- ↑ Adi Setia (2004). "Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on Physics and the Nature of the Physical World: A Preliminary Survey". Islam & Science. 2.

- ↑ Lewis, Neil (2021), "Robert Grosseteste", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University

- ↑ Kennedy, E. S. (1986-06-01). "The Astronomy of Levi ben Gerson (1288–1344): A Critical Edition of Chapters 1–20 with Translation and Commentary. Levi ben Gerson, Bernard R. Goldstein". Isis. 77 (2): 371–372.

- ↑ Kirschner, Stefan (2021), "Nicole Oresme", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University

- ↑ "Episode 11: The Legacy of Ptolemy's Almagest". www.aip.org. 2022-09-28.

- ↑ Hagen, J. (1911). "Nicholas of Cusa". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ Dick, Steven J. Plurality of Worlds: The Extraterrestrial Life Debate from Democritus to Kant. Cambridge University Press (June 29, 1984). pgs 35-42.

- ↑ George G. Joseph (2000). The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, p. 408. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ "Nicolaus Copernicus - University of Bologna". www.unibo.it.

- ↑ Hellyer, Marcus, ed. (2008). The Scientific Revolution: The Essential Readings. Blackwell Essential Readings in History. Vol. 7. John Wiley & Sons. p. 63. "청교도 토머스 디지스 (1546–1595?)는 코페르니쿠스 이론을 옹호한 최초의 영국인이었다... 디지스의 설명과 함께, 디지스가 모든 차원에서 무한히 확장된 것으로 묘사한 고정된 별들의 궤도로 둘러싸인 태양 중심계를 묘사한 우주의 다이어그램이다."

- ↑ Bruno, Giordano. "Third Dialogue". On the infinite universe and worlds. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012.

- ↑ Hatch, Robert. "Early Geo-Heliocentric models". The Scientific Revolution. Dr. Robert A. Hatch. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ↑ Gilbert, William (1893). "Book 6, Chapter III". De Magnete. Translated by Mottelay, P. Fleury. (Facsimile). New York: Dover Publications.

- ↑ Taton, René; Wilson, Curtis (1989). Planetary astronomy from the Renaissance to the rise of astrophysics. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Galileo Galilei, Sidereus Nuncius (Venice, (Italy): Thomas Baglioni, 1610), pages 15 and 16. Archived March 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine English translation: Galileo Galilei with Edward Stafford Carlos, trans., The Sidereal Messenger (London: Rivingtons, 1880), pages 42 and 43. Archived December 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Christian Frisch, ed., Joannis Kepleri Astronomi Opera Omnia, vol. 6 (Frankfurt-am-Main, (Germany): Heyder & Zimmer, 1866), page 361.)

- ↑ ""Astronomical Unit," or Earth-Sun Distance, Gets an Overhaul". Scientific American.

- ↑ Bobis, Laurence; Lequeux, James (2008). "Cassini, Rømer and the velocity of light". J. Astron. Hist. Herit. 11 (2): 97–105.

- ↑ Bartusiak, Marcia (2004). Archives of the universe : a treasury of astronomy's historic works of discovery (1st ed.). New York: Pantheon Books.

- ↑ "solar (adj.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022.

- ↑ Otto Neugebauer (1975). A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. Birkhäuser. p. 1084.

- ↑ Bradley, James (1727–1728). "A Letter from the Reverend Mr. James Bradley Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, and F.R.S. to Dr.Edmond Halley Astronom. Reg. &c. Giving an Account of a New Discovered Motion of the Fix'd Stars". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 35 (406): 637–661.

- ↑ "Original Messier Catalog of 1781". Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. 10 November 2007.

- ↑ 가 나 Berendzen, Richard (1975). "Geocentric to heliocentric to galactocentric to acentric: the continuing assault to the egocentric". Vistas in Astronomy. 17 (1): 65–83. Bibcode:1975VA.....17...65B.

- ↑ Owen, T. C. (2001) "Solar system: origin of the solar system", Encyclopædia Britannica, Deluxe CDROM edition

- ↑ Henderson, Thomas (1839). "On the Parallax of α Centauri". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 4 (19): 168–170. Bibcode:1839MNRAS...4..168H.

- ↑ Bessel, F. W. (1838b). "On the parallax of 61 Cygni". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 4 (17): 152–161.

- ↑ Alec Eden The search for Christian Doppler, Springer-Verlag, Wien 1992.

- ↑ Fizeau: "Acoustique et optique". Lecture, Société Philomathique de Paris, 29 December 1848. According to Becker(pg. 109), this was never published, but recounted by M. Moigno(1850): "Répertoire d'optique moderne" (in French), vol 3. pp 1165–1203 and later in full by Fizeau, "Des effets du mouvement sur le ton des vibrations sonores et sur la longeur d'onde des rayons de lumière"; [Paris, 1870]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 19, 211–221.

- ↑ Pohle, J. (1913). "Angelo Secchi" . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. “[...][그의] 세계의 통합과 항성과 태양의 정체에 대한 이론은 가장 심오한 과학적 증명과 확인을 받았다."

- ↑ Michelson, Albert A.; Morley, Edward W. (1887). "On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether". American Journal of Science. 34 (203): 333–345.

- ↑ Arabatzis, T. (2006). Representing Electrons: A Biographical Approach to Theoretical Entities. University of Chicago Press. pp. 70–74, 96.

- ↑ Thomson, William (1862). "On the Age of the Sun's Heat". Macmillan's Magazine. Vol. 5. pp. 388–393.

- ↑ England, P.; Molnar, P.; Righter, F. (January 2007). "John Perry's neglected critique of Kelvin's age for the Earth: A missed opportunity in geodynamics". GSA Today. Vol. 17, no. 1. pp. 4–9. doi:10.1130/GSAT01701A.1.

- ↑ Bohr, N. (July 1913). "I. On the constitution of atoms and molecules". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 26 (151): 1–25.

- ↑ Glass, I.S. (2008). Proxima, the Nearest Star (other than the Sun). Cape Town: Mons Mensa.

- ↑ Dyson, F.W.; Eddington, A.S.; Davidson, C.R. (1920). "A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun's Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 220 (571–581): 291–333.

- ↑ Evans, Ben (April 25, 2020). "The Great Debate - 100 years later". Astronomy.com.

- ↑ Feynman, R., QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Penguin 1990 Edition, p. 84.

- ↑ Davisson, C. J.; Germer, L. H. (1928). "Reflection of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 14 (4): 317–322.

- ↑ Dirac, P. A. M. (1928). "The Quantum Theory of the Electron". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 117 (778): 610–624.

- ↑ Anderson, C. D. (1933). "The Positive Electron". Physical Review. 43 (6): 491–494.

- ↑ 92] "Three steps to the Hubble constant". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ↑ Karl Jansky (Oct 1933). "Electrical Disturbances Apparently of Extraterrestrial Origin". Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers. 21 (10): 1387–1398. See also Karl Jansky (Jul 8, 1933). "Radio Waves from Outside the Solar System" (PDF). Nature. 132 (3323): 66.

- ↑ Bethe, H.; Critchfield, C. (1938). "On the Formation of Deuterons by Proton Combination". Physical Review. 54 (10): 862. Bibcode:[Bethe, H.; Critchfield, C. (1938). "On the Formation of Deuterons by Proton Combination". Physical Review. 54 (10): 862. Bibcode:1938PhRv...54Q.862B. 1938PhRv...54Q.862B].

- ↑ Bethe, H. (1939). "Energy Production in Stars". Physical Review. 55 (1): 434–456. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..434B.

- ↑ [ "STS-31". NASA. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2008. "STS-31"]. NASA. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ↑ Wolszczan, A.; Frail, D. (1992). "A planetary system around the millisecond pulsar PSR1257 + 12". Nature. 355 (6356): 145–147. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..145W.

- ↑ Mayor, Michael; Queloz, Didier (1995). "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star". Nature. 378 (6555): 355–359. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..355M.

- ↑ "Voyager 1 Sees Solar Wind Decline". NASA. December 13, 2010.

- ↑ Staff (March 17, 2014). "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation.

- ↑ Clavin, Whitney (March 17, 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". NASA.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang's Smoking Gun". The New York Times.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (March 24, 2014). "Ripples From the Big Bang". New York Times.

- ↑ 가 나 Ade, P.A.R.; BICEP2 Collaboration (June 19, 2014). "Detection of B-Mode Polarization at Degree Angular Scales by BICEP2". Physical Review Letters. 112 (24): 241101. arXiv:1403.3985.

- ↑ "BICEP2 News | Not Even Wrong".

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (June 19, 2014). "Astronomers Hedge on Big Bang Detection Claim". New York Times.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (June 19, 2014). "Cosmic inflation: Confidence lowered for Big Bang signal". BBC News.

- ↑ Abbott, B. P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T. D.; Abernathy, M. R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P. (2016-02-11). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Physical Review Letters. 116 (6): 061102. arXiv:[Abbott, B. P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T. D.; Abernathy, M. R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P. (2016-02-11). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Physical Review Letters. 116 (6): 061102. arXiv:1602.03837. 1602.03837].

- ↑ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Alexandra (11 February 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News.

- ↑ Blum, Alexander; Lalli, Roberto; Renn, Jürgen (12 February 2016). "The long road towards evidence". Max Planck Society.

- ↑ Abbott, B. P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (15 June 2016). "GW151226: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a 22-Solar-Mass Binary Black Hole Coalescence". Physical Review Letters. 116 (24): 241103. arXiv:1606.04855.

- ↑ Commissariat, Tushna (15 June 2016). "LIGO detects second black-hole merger". Physics World. Institute of Physics.

- ↑ "First-ever Image of a Black Hole Published by the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration". eventhorizontelescope.org. Retrieved 2020-03-30.

- ↑ "The first picture of a black hole opens a new era of astrophysics". Science News. 2019-04-10.

- ↑ "How Does the Event Horizon Telescope Work?". Sky & Telescope. 2019-04-15.

- ↑ University of Geneva (10 March 2020). "Solved: The mystery of the expansion of the universe". Phys.org.

- ↑ Lombriser, Lucas (10 April 2020). "Consistency of the local Hubble constant with the cosmic microwave background". Physics Letters B. 803: 135303. arXiv:1906.12347.

- ↑ "Rethinking cosmology: Universe expansion may not be uniform (Update)". phys.org. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ "Nasa study challenges one of our most basic ideas about the universe". The Independent. 8 April 2020.

- ↑ "Parts of the universe may be expanding faster than others". New Atlas. 9 April 2020.

- ↑ [121] "Doubts about basic assumption for the universe". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 May 2020. "Doubts about basic assumption for the universe"]. EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ↑ Migkas, K.; Schellenberger, G.; Reiprich, T. H.; Pacaud, F.; Ramos-Ceja, M. E.; Lovisari, L. (8 April 2020). "Probing cosmic isotropy with a new X-ray galaxy cluster sample through the LX–T scaling relation". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 636: A15.

- ↑ 123] "The laws of physics may break down at the edge of the universe". Futurism. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ "New findings suggest laws of nature 'downright weird,' not as constant as previously thought". phys.org. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ Field, David (28 April 2020). "New Tests Suggest a Fundamental Constant of Physics Isn't The Same Across The Universe". ScienceAlert.com.

- ↑ 126] Wilczynska, Michael R.; Webb, John K.; Bainbridge, Matthew; Barrow, John D.; Bosman, Sarah E. I.; Carswell, Robert F.; Dąbrowski, Mariusz P.; Dumont, Vincent; Lee, Chung-Chi; Leite, Ana Catarina; Leszczyńska, Katarzyna; Liske, Jochen; Marosek, Konrad; Martins, Carlos J. A. P.; Milaković, Dinko; Molaro, Paolo; Pasquini, Luca (1 April 2020). "Four direct measurements of the fine-structure constant 13 billion years ago". Science Advances. 6 (17): eaay9672.

- ↑ "Ariane 5 goes down in history with successful launch of Webb". Arianespace (Press release). 25 December 2021.

- ↑ Frank, Adam; Gleiser, Marcelo (2 September 2023). "The Story of Our Universe May Be Starting to Unravel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

참고 문헌[편집]

- Bunch, Bryan, and Alexander Hellemans, The History of Science and Technology: A Browser's Guide to the Great Discoveries, Inventions, and the People Who Made Them from the Dawn of Time to Today.

- P. de Bernardis et al., astro-ph/0004404, Nature 404 (2000) 955–959.

- Horowitz, Wayne (1998). Mesopotamian cosmic geography. Eisenbrauns.

- P. Mauskopf et al., astro-ph/9911444, Astrophys. J. 536 (2000) L59–L62.

- A. Melchiorri et al., astro-ph/9911445, Astrophys. J. 536 (2000) L63–L66.

- A. Readhead et al., Polarization observations with the Cosmic Background Imager, Science 306 (2004), 836–844.