글루타티온

| |

| |

| 이름 | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC 이름

(2S)-2-Amino-4-{[(1R)-1-[(carboxymethyl)carbamoyl]-2-sulfanylethyl]carbamoyl}butanoic acid

| |

| 별칭

γ-L-Glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine

(2S)-2-Amino-5-[[(2R)-1-(carboxymethylamino)-1-oxo-3-sulfanylpropan-2-yl]amino]-5-oxopentanoic acid | |

| 식별자 | |

3D 모델 (JSmol)

|

|

| 약어 | GSH |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.660 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Glutathione |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| 성질 | |

| C10H17N3O6S | |

| 몰 질량 | 307.32 g·mol−1 |

| 녹는점 | 195 °C (383 °F; 468 K)[1] |

| Freely soluble[1] | |

| methanol, 다이에틸 에터에서의 용해도 | Insoluble[1] |

| 약리학 | |

| V03AB32 (WHO) | |

달리 명시된 경우를 제외하면, 표준상태(25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa)에서 물질의 정보가 제공됨.

| |

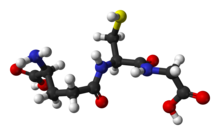

글루타티온(영어: glutathione 글루타싸이온[*], GSH)은 글루탐산, 시스테인, 글리신의 세 가지 아미노산으로 이루어진 결정성 펩타이드이자 식물, 동물, 균류 및 일부 세균과 고균에서의 항산화제이다. 글루타티온은 자유 라디칼, 과산화물, 지질 과산화물, 중금속과 같은 활성 산소로 인한 세포의 중요 성분의 손상을 방지할 수 있다.[2] 글루타티온은 글루탐산 곁사슬의 카복실기와 시스테인 사이에 γ-펩타이드 결합으로 연결되어 있고, 시스테인 잔기의 카복실기는 글리신과 정상적인 펩타이드 결합으로 연결된 트라이펩타이드이다.

합성 및 생성[편집]

글루타티온 생합성 과정은 아데노신 삼인산(ATP) 의존적인 두 가지 단계를 포함하는 과정이다.

- 첫 번째 단계에서 γ-글루타밀시스테인은 L-글루탐산과 시스테인으로부터 합성된다. 이러한 전환 과정에는 글루탐산-시스테인 연결효소(γ-글루타밀시스테인 합성효소)가 필요하다. 이 반응은 글루타티온 합성 과정에서의 속도 제한 단계이다.[3]

- 두 번째 단계에서 글리신은 γ-글루타밀시스테인의 C-말단에 첨가된다. 이러한 축합 반응은 글루타티온 합성효소에 의해 촉매된다.

모든 동물 세포가 글루타티온을 합성할 수 있고, 특히 간에서의 글루타티온 합성은 필수적인 것으로 나타났다. 글루탐산-시스테인 연결효소 촉매 소단위체(GCLC) 유전자제거 생쥐는 간에서 글루타티온을 합성할 수 없기 때문에 생후 1개월 이내에 사망한다.[4][5]

글루타티온의 특이한 γ-펩타이드 결합은 펩티데이스에 의한 가수분해로부터 글루타티온을 보호한다.[6]

생성[편집]

글루타티온은 동물 세포에 0.5~10 mM로 존재하는 가장 풍부한 싸이올이다. 글루타티온은 세포 기질과 세포 소기관에 모두 존재한다.[6]

사람은 글루타티온을 합성할 수 있지만, 콩과 식물, 엔트아메바, 람블편모충속을 포함한 일부 진핵 생물들은 글루타티온을 합성할 수 없다. 글루타티온을 만드는 유일한 고균은 할로박테리아이다. 남세균, 프로테오박테리아와 같은 일부 세균들은 글루타티온을 생합성할 수 있다.[7][8]

생화학적 기능[편집]

글루타티온은 환원형(GSH) 및 산화형(GSSG)으로 존재한다. 세포 내에서 산화된 글루타티온 대 환원된 글루타티온의 비는 세포의 산화 스트레스의 척도이다.[9][10] 건강한 세포 및 조직에서 총 글루타티온 풀의 90% 이상이 환원된 형태(GSH)이고, 나머지는 산화된 형태(GSSG)이다. GSSG 대 GSH 비율의 증가는 산화 스트레스를 나타낸다.[11]

산화된 상태에서 시스테닐 잔기의 설프하이드릴기는 1가의 환원 당량의 공급원이다. 이에 따라 글루타티온 이황화물(GSSG)이 생성된다. 산화된 상태는 NADPH에 의해 환원된 상태로 전환된다.[12] 이러한 전환 과정은 글루타티온 환원효소에 의해 촉매된다.

- NADPH + GSSG + H2O → 2 GSH + NADP+ + OH-

역할[편집]

항산화제[편집]

환원된 형태의 글루타티온(GSH)은 활성 산소를 환원시켜 세포를 보호한다.[6][13] 이러한 전환은 과산화물의 환원으로 설명된다.

- 2 GSH + R2O2 → GSSG + 2 ROH (R = H, alkyl)

다음은 자유 라디칼과의 반응이다.

- GSH + R. → 0.5 GSSG + RH

조절[편집]

글루타티온은 불활성 라디칼 및 반응성 산화제 외에, 산화환원 조절된 번역 후 변형 과정에서의 싸이올 변형인 단백질의 S-글루타티오닐화에 의해 산화 스트레스 하에서 세포성 싸이올 단백질의 싸이올 보호 및 산화환원 조절에 참여한다. 일반적인 반응은 보호가능한 단백질(RSH) 및 환원된 글루타티온(GSH)으로부터 비대칭 이황화물의 형성을 포함한다.[14]

- RSH + GSH + [O] → GSSR + H2O

글루타티온은 산화 스트레스 하에서 생성되는 독성 대사산물인 메틸글리옥살 및 폼알데하이드 해독에도 사용된다. 이러한 해독 반응은 글리옥살레이스 시스템에 의해 수행된다. 글리옥살레이스 I (EC 4.4.1.5)은 메틸글리옥살 및 환원된 글루타티온의 S-D-락토일-글루타티온으로의 전환을 촉매한다. 글리옥살레이스 II (EC 3.1.2.6)는 S-D-락토일-글루타티온의 글루타티온 및 D-락트산으로의 가수분해를 촉매한다.

비타민 C 및 비타민 E와 같은 외인성 항산화제는 환원성(활성) 상태로 유지된다.[15][16][17]

물질대사[편집]

많은 대사 과정 중에서 류코트라이엔과 프로스타글란딘의 생합성 과정에 글루타티온이 필요하다. 글루타티온은 시스테인 저장에 중요한 역할을 한다. 글루타티온은 산화 질소 순한의 일부로 시트룰린의 작용을 증강시킨다.[18] 글루타티온은 보조 인자이며, 글루타티온 퍼옥시데이스에 작용한다.[19]

공액[편집]

글루타티온은 비생체물질의 물질대사를 촉진시킨다. 글루타티온 S-트랜스퍼레이스는 소수성인 비생체물질과의 공액을 촉매하여, 배설 또는 추가적인 대사를 촉진한다.[20] 공액 과정은 N-아세틸-p-벤조퀴논 이민(NAPQI)의 대사에 의해 설명된다. N-아세틸-p-벤조퀴논 이민은 아세트아미노펜(파라세타몰)에 대한 사이토크롬 P450의 작용에 의해 형성되는 반응성 대사산물이다. 글루타티온은 N-아세틸-p-벤조퀴논 이민과 공액되어 배설된다.

잠재적 신경전달물질[편집]

글루타티온은 산화된 글루타티온(GSSG) 및 S-나이트로소글루타티온(GSNO)와 함께 NMDA 수용체 및 AMPA 수용체의 글루탐산 인식 부위의 이들 분자의 γ-글루타밀 부분을 통해 결합한다. GSH 및 GSSG는 신경조절물질일 수 있다.[21][22][23] 밀리몰 농도에서 GSH 및 GSSG는 또한 NMDA 수용체 복합체의 산화환원 상태를 조절할 수 있다.[22] 글루타티온은 리간드 개폐 이온 통로에 결합하고 이를 활성화시켜 잠재적인 신경전달물질로 작용할 수 있다.[24]

GSH는 뮐러 신경교세포로부터 퓨린작동성 P2X7 수용체를 활성화시켜 망막 뉴런과 신경교세포에서 일시적인 칼슘 신호 및 γ-아미노뷰티르산(GABA)의 방출을 유도한다.[25][26]

식물에서[편집]

식물에서 글루타티온은 스트레스 관리에 관여한다. 글루타티온은 독성이 있는 과산화 수소를 감소시키는 시스템인 글루타티온-아스코르브산 회로의 구성 요소이다.[27] 글루타티온은 카드뮴과 같은 중금속을 킬레이트하는 피토킬라틴, 글루타티온 올리고머의 전구체이다.[28] 글루타티온은 슈도모나스 시링가에(Pseudomonas syringae) 및 피토프토라 브라시카에(Phytophthora brassicae)와 같은 식물의 병원체에 대한 효율적인 방어 작용을 위해 필요하다.[29] 황 동화 경로의 효소인 아데닐릴-황산 환원효소는 글루타티온을 전자 공여체로 사용한다. 글루타티온을 기질로 사용하는 다른 효소로는 글루타레독신이 있다. 이 조그마한 산화환원효소는 꽃 발생, 살리실산 및 식물의 방어 신호전달에 관여한다.[30]

생체 이용률 및 보충[편집]

경구 섭취된 글루타티온의 전신 생체 이용률은 트라이펩타이드가 소화관의 프로테에이스의 기질이고, 세포막 수준에서 글루타티온에 대한 특정 운반체가 없기 때문에 상당히 낮다.[31][32]

글루타티온의 직접적인 보충은 성공적이지 못하기 때문에, 시스테인 및 글리신과 같은 글루타티온 생성에 사용되는 원료 영양물질의 공급이 글루타티온의 수준을 높이는 데 보다 더 효과적일 수 있다. 아스코르브산(비타민 C)와 같은 다른 항산화제는 글루타티온과 상승적으로 작용하여 고갈을 방지할 수 있다. 과산화 수소(H2O2)를 해독하기 위해 작용하는 글루타티온-아스코르브산 회로는 이러한 현상의 매우 구체적인 예 중 하나이다.

또한 아세틸시스테인[33] 및 α-리포산[34](관련이 없는 α-리놀렌산과 혼동하지 않아야 함)과 같은 화합물은 글루타티온의 재생을 도울 수 있다. 특히 아세틸시스테인은 글루타티온의 심각한 고갈로 인해 부분적으로 유해한 잠재적으로 치명적인 중독의 일종인 아세트아미노펜의 과다 복용을 치료하는 데 일반적으로 사용된다. 아세틸시스테인은 시스테인의 전구체이다.

비타민 D3의 활성 대사산물인 칼시트라이올(1,25-다이하이드록시비타민 D3)은 콩팥에서 칼시페다이올로부터 합성된 후 뇌에서 글루타티온의 수준을 증가시키고, 글루타티온을 생성하기 위한 촉매로 보인다.[35] 신체가 비타민 D3를 칼시트라이올로 처리하는 과정은 약 10일이 걸린다.[36]

메틸기 전이에 관여하는 보조 인자인 S-아데노실메티오닌은 또한 질병 관련 글루타티온 결핍으로 고통받는 환자들에서 세포 내 글루타티온의 함량을 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다.[37][38][39]

낮은 수준의 글루타티온은 암, AIDS, 패혈증, 외상, 화상 및 운동과 훈련에서 볼 수 있듯이 낭비성 및 음성 질소 균형에서 일반적으로 관찰된다. 또한 글루타티온은 기아시에도 낮은 수준으로 관찰된다. 이러한 효과는 산화적 인산화 수준의 감소로 인한 악액질과 관련된 더 높은 해당과정의 활성에 의해 영향을 받는 것으로 가정된다.[40][41]

글루타티온의 측정[편집]

엘만 시약 및 모노브로모바이메인[편집]

환원된 글루타티온은 엘만 시약 또는 모노브로모바이메인과 같은 바이메인 유도체를 사용하여 시각화될 수 있다. 모노브로모바이메인을 사용한 방법이 더 민감하다. 이 과정에서 세포를 용해시키고 HCl 완충 용액을 사용하여 싸이올을 추출한다. 싸이올은 이어서 다이싸이오트레이톨로 환원되고, 모노브로모바이메인으로 표지된다. 모노브로모바이메인은 글루타티온에 결합한 후에 형광을 띤다. 이어서 싸이올을 고성능 액체 크로마토그래피(HPLC)로 분리하고 형광을 형광 검출기로 정량화한다.

모노클로로바이메인[편집]

모노클로로바이메인을 사용하여 살아있는 세포를 염색한 후 공초점 현미경으로 정량화한다.[42] 이러한 정량화 과정은 형광 변화율 측정에 의존하며, 식물 세포로 제한된다.

5-클로로메틸플루오레세인 다이아세트산(CMFDA)은 또한 글루타티온 탐침으로 잘못 사용되어 왔다. 글루타티온과 반응할 때 형광이 증가하는 모노클로로바이메인과는 달리, CMFDA의 형광 증가는 세포 내 아세틸기의 가수분해로 인한 것이다. CMFDA는 세포에서 글루타티온과 반응할 수 있지만, 형광의 증가는 이러한 반응을 반영하지는 않는다. 따라서 CMFDA를 글루타티온 탐침으로 사용하는 연구는 재검토하고 재해석되어야 한다.[43][44]

싸이올퀀트 그린[편집]

이러한 바이메인 기반 탐침 및 기타 보고된 많은 탐침들의 주요 제한 사항은 이러한 탐침들이 글루타티온과 비가역적인 화학 반응을 기반으로 하기 때문에 실시간으로 글루타티온을 모니터링 할 수 없다는 것이다. 최근, 글루타티온에 대한 형광 탐침-싸이올퀀트 그린(TQG) 기반의 가역적 반응이 보고되었다.[45] 싸이올퀀트 그린은 공초점 현미경을 사용하여 단일 세포에서 글루타티온 수치의 고해상도 측정을 수행할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 다량의 세포를 측정하기 위해 유세포 분석에 적용할 수도 있다.

리얼싸이올[편집]

리얼싸이올(RT) 탐침은 2세대 가역 반응 기반의 글루타티온 탐침이다. 리얼싸이올의 몇 가지 주요 기능들은 다음과 같다. 1) 리얼싸이올은 싸이올퀀트 그린에 비해 순방향 및 역방향 반응 속도가 훨씬 더 빠르기 때문에 살아있는 세포에서 글루타티온을 실시간으로 모니터링할 수 있다. 2) 세포 기반 실험에서 염색에 마이크로몰 미만의 리얼싸이올이 필요하며 이는 세포에서 글루타티온 수치의 최소한의 변화를 유도한다. 3) 배경 노이즈가 최소화될 수 있도록 고수율의 쿠마린 형광단이 구현되었다. 4) 리얼싸이올과 글루타티온 간의 반응 평형 상수는 생리적으로 관련된 글루타티온의 농도에 반응하도록 미세 조정되었다.[46] 리얼싸이올은 고해상도 공초점 현미경을 사용하여 단일 세포에서 글루타티온 수치의 측정을 수행할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 유세포 분석을 적용하여 대량 측정을 수행할 수 있다.

세포소기관 표적 리얼싸이올(RT) 탐침도 개발되었다. 미토콘드리아에 표적화된 버전인 MitoRT가 보고되었고, 공초점 현미경 및 FACS 기반 분석 둘 다에서 미토콘드리아의 글루타티온의 역동성을 모니터링 하는 것으로 입증되었다.[47]

단백질 기반 글루타티온 탐침[편집]

생리학적으로 매우 낮은 농도에서는 절차를 주의 깊게 수행하고 불순물의 생성을 적절하게 다루지 않으면 정확하게 측정하기 어렵기 때문에 살아있는 세포에서 공간적, 시간적으로 높은 해상도에서 글루타티온의 산화환원 전위를 측정할 수 있는 또 다른 접근법은 산화환원 감수성 녹색 형광 단백질(roGFP)[48] 또는 산화환원 감수성 황색 형광 단백질(rxYFP)[49] GSSG를 사용한 산화환원 영상화에 기초한다. GSSG의 농도는 모든 고형 조직에서 10~50 μM, 혈액에서 2~5 μM이다. GSH 대 GSSG의 비율은 100~700 사이이다.[50] 그러나, 이들 비는 상이한 세포 내 구획(예를 들어, 소포체에서 보다는 산화되고, 미토콘드리아 기질에서보다는 환원됨)으로부터 상이한 산화환원 상태의 글루타티온 풀로부터의 혼합물을 나타낸다. 생체 내 GSH 대 GSSG 비는 세포기질에서 50,000~500,000의 비를 나타내는 형광 단백질 기반의 산화환원 센서를 사용하여 세포 내 정확도로 측정될 수 있으며, 이는 GSSG 농도가 pM 범위로 유지됨을 의미한다.[51]

기타 생물학적 영향[편집]

납[편집]

글루타티온의 설프하이드릴기는 납(II)과 상대적으로 강한 복합체를 형성한다.[52]

암[편집]

일단 종양이 형성되면, 높은 수준의 글루타티온이 화학 요법 약물에 대한 내성을 부여함으로써 암세포를 보호하도록 작용할 수 있다.[53] 항신생물제 머스터드 약물인 칸포스파미드는 글루타티온의 구조에 관해 모델링되었다.

낭포성 섬유증[편집]

낭포성 섬유증 환자들에게 흡입된 글루타티온을 도입하는 것의 효과에 대한 몇 가지 연구가 완료되었다.[54][55]

알츠하이머병[편집]

세포 외 아밀로이드 베타(Aβ) 플라크, 신경섬유매듭(NFT), 반응성 별아교세포 및 미세아교세포의 염증 및 뉴런 손실은 모두 알츠하이머병의 일관된 병리학적 특징이지만, 이들 인자들 사이의 기계적인 연관성은 아직 명확히 밝혀지지 않았다. 과거에 대부분의 연구들은 섬유상 아밀로이드 베타에 초점을 맞추었지만, 가용성 올리고머 아밀로이드 베타 종은 현재 알츠하이머병에서 병리학적 중요성을 갖는 것으로 간주된다. 글루타티온의 상향 조절은 올리고머 아밀로이드 베타 및 신경독성 효과에 대해 보호적일 수 있다.

해마에서 폐쇄형의 글루타티온이 고갈되면 알츠하이머병의 조기 진단 바이오마커가 될 수 있다.[56][57]

용도[편집]

포도주 양조법[편집]

포도주의 첫 번째 원료 형태인 머스트에서 글루타티온의 함량은 포도 반응 생성물로서 효소적인 산화에 의해 생성된 카페오일타타르산 및 퀴논을 포획함으로써 백포도주를 생성하는 동안 갈변 또는 캐러멜화 효과를 결정한다.[58] 포도주에서 글루타티온의 농도는 UPLC-MRM 질량 분석법에 의해 결정될 수 있다.[59]

화장품[편집]

글루타티온은 피부톤을 밝게 위해 입으로 복용하는 가장 흔한 물질이다.[60] 글루타티온은 크림으로도 사용할 수 있다.[60][60] 실제로 작용하는 지에 대한 여부는 2019년을 기준으로 불분명하다.[61] 정맥 투여로 인한 부작용 때문에 필리핀 정부는 그러한 사용을 권장하지 않는다.[62]

같이 보기[편집]

- 환원 스트레스

- 글루타티온 합성효소 결핍증

- 오프탈민산

- 산화환원 감수성 녹색 형광 단백질 (roGFP): 세포의 글루타티온 산화환원 전위를 측정하는 도구

- 글루타티온-아스코르브산 회로

- 세균의 글루타티온 전이효소

- 싸이레독신: 환원제와 매우 유사한 기느을 하는 시스테인을 함유한 작은 단백질

- 글루타레독신: 환원된 글루타티온을 보조 인자로 사용하고 이것에 의해 비효소적으로 환원되는 항산화 단백질

- 바실리싸이올

- 미코싸이올

- γ-글루타밀시스테인

각주[편집]

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Haynes, William M., 편집. (2016). 《CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics》 97판. CRC Press. 3.284쪽. ISBN 9781498754293.

- ↑ Pompella A, Visvikis A, Paolicchi A, De Tata V, Casini AF (October 2003). “The changing faces of glutathione, a cellular protagonist”. 《Biochemical Pharmacology》 66 (8): 1499–503. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00504-5. PMID 14555227.

- ↑ White CC, Viernes H, Krejsa CM, Botta D, Kavanagh TJ (July 2003). “Fluorescence-based microtiter plate assay for glutamate-cysteine ligase activity”. 《Analytical Biochemistry》 318 (2): 175–80. doi:10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00143-X. PMID 12814619.

- ↑ Chen Y, Yang Y, Miller ML, Shen D, Shertzer HG, Stringer KF, Wang B, Schneider SN, Nebert DW, Dalton TP (May 2007). “Hepatocyte-specific Gclc deletion leads to rapid onset of steatosis with mitochondrial injury and liver failure”. 《Hepatology》 45 (5): 1118–28. doi:10.1002/hep.21635. PMID 17464988.

- ↑ Sies H (1999). “Glutathione and its role in cellular functions”. 《Free Radical Biology & Medicine》 27 (9–10): 916–21. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00177-X. PMID 10569624.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Guoyao Wu, Yun-Zhong Fang, Sheng Yang, Joanne R. Lupton, Nancy D. Turner (2004). “Glutathione Metabolism and its Implications for Health”. 《Journal of Nutrition》 134 (3): 489–92. doi:10.1093/jn/134.3.489. PMID 14988435.

- ↑ Copley SD, Dhillon JK (2002년 4월 29일). “Lateral gene transfer and parallel evolution in the history of glutathione biosynthesis genes”. 《Genome Biology》 3 (5): research0025. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-research0025. PMC 115227. PMID 12049666.

- ↑ Wonisch W, Schaur RJ (2001). 〈Chapter 2: Chemistry of Glutathione〉. Grill D, Tausz T, De Kok LJ. 《Significance of glutathione in plant adaptation to the environment》. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-0178-9 – Google Books 경유.

- ↑ Pastore A, Piemonte F, Locatelli M, Lo Russo A, Gaeta LM, Tozzi G, Federici G (August 2001). “Determination of blood total, reduced, and oxidized glutathione in pediatric subjects”. 《Clinical Chemistry》 47 (8): 1467–9. PMID 11468240.

- ↑ Lu SC (May 2013). “Glutathione synthesis”. 《Biochimica et Biophysica Acta》 1830 (5): 3143–53. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008. PMC 3549305. PMID 22995213.

- ↑ Halprin KM, Ohkawara A (1967). “The measurement of glutathione in human epidermis using glutathione reductase”. 《The Journal of Investigative Dermatology》 48 (2): 149–52. doi:10.1038/jid.1967.24. PMID 6020678.

- ↑ Couto N, Malys N, Gaskell SJ, Barber J (June 2013). “Partition and turnover of glutathione reductase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a proteomic approach”. 《Journal of Proteome Research》 12 (6): 2885–94. doi:10.1021/pr4001948. PMID 23631642.

- ↑ Michael Brownlee (2005). “The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism”. 《Diabetes》 54 (6): 1615–25. doi:10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. PMID 15919781.

- ↑ Dalle-Donne, Isabella; Rossi, Ranieri; Colombo, Graziano; Giustarini, Daniela; Milzani, Aldo (2009). “Protein S-glutathionylation: a regulatory device from bacteria to humans”. 《Trends in Biochemical Sciences》 34 (2): 85–96. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2008.11.002. PMID 19135374.

- ↑ Dringen R (December 2000). “Metabolism and functions of glutathione in brain”. 《Progress in Neurobiology》 62 (6): 649–71. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00060-x. PMID 10880854.

- ↑ Scholz, RW. Graham KS. Gumpricht E. Reddy CC. (1989). “Mechanism of interaction of vitamin E and glutathione in the protection against membrane lipid peroxidation”. 《Ann NY Acad Sci》 570 (1): 514–7. Bibcode:1989NYASA.570..514S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb14973.x.

- ↑ Hughes RE (1964). “Reduction of dehydroascorbic acid by animal tissues”. 《Nature》 203 (4949): 1068–9. Bibcode:1964Natur.203.1068H. doi:10.1038/2031068a0. PMID 14223080.

- ↑ Ha SB, Smith AP, Howden R, Dietrich WM, Bugg S, O'Connell MJ, Goldsbrough PB, Cobbett CS (June 1999). “Phytochelatin synthase genes from Arabidopsis and the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe”. 《The Plant Cell》 11 (6): 1153–64. doi:10.1105/tpc.11.6.1153. JSTOR 3870806. PMC 144235. PMID 10368185.

- ↑ Grant CM (2001). “Role of the glutathione/glutaredoxin and thioredoxin systems in yeast growth and response to stress conditions”. 《Molecular Microbiology》 39 (3): 533–41. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02283.x. PMID 11169096.

- ↑ Hayes, John D.; Flanagan, Jack U.; Jowsey, Ian R. (2005). “Glutathione transferases”. 《Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology》 45: 51–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. PMID 15822171.

- ↑ Steullet P, Neijt HC, Cuénod M, Do KQ (February 2006). “Synaptic plasticity impairment and hypofunction of NMDA receptors induced by glutathione deficit: relevance to schizophrenia”. 《Neuroscience》 137 (3): 807–19. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.014. PMID 16330153.

- ↑ 가 나 Varga V, Jenei Z, Janáky R, Saransaari P, Oja SS (September 1997). “Glutathione is an endogenous ligand of rat brain N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) receptors”. 《Neurochemical Research》 22 (9): 1165–71. doi:10.1023/A:1027377605054. PMID 9251108.

- ↑ Janáky R, Ogita K, Pasqualotto BA, Bains JS, Oja SS, Yoneda Y, Shaw CA (September 1999). “Glutathione and signal transduction in the mammalian CNS”. 《Journal of Neurochemistry》 73 (3): 889–902. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730889.x. PMID 10461878.

- ↑ Oja SS, Janáky R, Varga V, Saransaari P (2000). “Modulation of glutamate receptor functions by glutathione”. 《Neurochemistry International》 37 (2–3): 299–306. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(00)00031-0. PMID 10812215.

- ↑ Freitas HR, Ferraz G, Ferreira GC, Ribeiro-Resende VT, Chiarini LB, do Nascimento JL, Matos Oliveira KR, Pereira Tde L, Ferreira LG, Kubrusly RC, Faria RX, Herculano AM, Reis RA (2016년 4월 14일). “Glutathione-Induced Calcium Shifts in Chick Retinal Glial Cells”. 《PLOS ONE》 11 (4): e0153677. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1153677F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153677. PMC 4831842. PMID 27078878.

- ↑ Freitas HR, Reis RA (2017년 1월 1일). “Glutathione induces GABA release through P2X7R activation on Müller glia”. 《Neurogenesis》 4 (1): e1283188. doi:10.1080/23262133.2017.1283188. PMC 5305167. PMID 28229088.

- ↑ Noctor G, Foyer CH (June 1998). “Ascorbate and Glutathione: Keeping Active Oxygen Under Control”. 《Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology》 49 (1): 249–279. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249. PMID 15012235.

- ↑ Ha SB, Smith AP, Howden R, Dietrich WM, Bugg S, O'Connell MJ, Goldsbrough PB, Cobbett CS (June 1999). “Phytochelatin synthase genes from Arabidopsis and the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe”. 《The Plant Cell》 11 (6): 1153–64. doi:10.1105/tpc.11.6.1153. PMC 144235. PMID 10368185.

- ↑ Parisy V, Poinssot B, Owsianowski L, Buchala A, Glazebrook J, Mauch F (January 2007). “Identification of PAD2 as a gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase highlights the importance of glutathione in disease resistance of Arabidopsis” (PDF). 《The Plant Journal》 49 (1): 159–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02938.x. PMID 17144898.

- ↑ Rouhier N, Lemaire SD, Jacquot JP (2008). “The role of glutathione in photosynthetic organisms: emerging functions for glutaredoxins and glutathionylation”. 《Annual Review of Plant Biology》 59 (1): 143–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092811. PMID 18444899.

- ↑ Allen J, Bradley RD (September 2011). “Effects of oral glutathione supplementation on systemic oxidative stress biomarkers in human volunteers”. 《Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine》 17 (9): 827–33. doi:10.1089/acm.2010.0716. PMC 3162377. PMID 21875351.

- ↑ Witschi A, Reddy S, Stofer B, Lauterburg BH (1992). “The systemic availability of oral glutathione”. 《European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology》 43 (6): 667–9. doi:10.1007/bf02284971. PMID 1362956.

- ↑ “Acetylcysteine Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com”.

- ↑ Zhang J, Zhou X, Wu W, Wang J, Xie H, Wu Z (2017). “Regeneration of glutathione by α-lipoic acid via Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway alleviates cadmium-induced HepG2 cell toxicity”. 《Environ Toxicol Pharmacol》 51: 30–37. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2017.02.022. PMID 28262510.

- ↑ Garcion E, Wion-Barbot N, Montero-Menei CN, Berger F, Wion D (April 2002). “New clues about vitamin D functions in the nervous system”. 《Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism》 13 (3): 100–5. doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00547-1. PMID 11893522.

- ↑ van Groningen L, Opdenoordt S, van Sorge A, Telting D, Giesen A, de Boer H (April 2010). “Cholecalciferol loading dose guideline for vitamin D-deficient adults”. 《European Journal of Endocrinology》 162 (4): 805–11. doi:10.1530/EJE-09-0932. PMID 20139241.

- ↑ Lieber CS (November 2002). “S-adenosyl-L-methionine: its role in the treatment of liver disorders”. 《The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition》 76 (5): 1183S–7S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1183s. PMID 12418503.

- ↑ Vendemiale G, Altomare E, Trizio T, Le Grazie C, Di Padova C, Salerno MT, Carrieri V, Albano O (May 1989). “Effects of oral S-adenosyl-L-methionine on hepatic glutathione in patients with liver disease”. 《Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology》 24 (4): 407–15. doi:10.3109/00365528909093067. PMID 2781235.

- ↑ Loguercio C, Nardi G, Argenzio F, Aurilio C, Petrone E, Grella A, Del Vecchio Blanco C, Coltorti M (September 1994). “Effect of S-adenosyl-L-methionine administration on red blood cell cysteine and glutathione levels in alcoholic patients with and without liver disease”. 《Alcohol and Alcoholism》 29 (5): 597–604. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a045589. PMID 7811344.

- ↑ Dröge W, Holm E (November 1997). “Role of cysteine and glutathione in HIV infection and other diseases associated with muscle wasting and immunological dysfunction”. 《FASEB Journal》 11 (13): 1077–89. doi:10.1096/fasebj.11.13.9367343. PMID 9367343.

- ↑ Tateishi N, Higashi T, Shinya S, Naruse A, Sakamoto Y (January 1974). “Studies on the regulation of glutathione level in rat liver”. 《Journal of Biochemistry》 (영어) 75 (1): 93–103. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a130387. PMID 4151174.

- ↑ Meyer AJ, May MJ, Fricker M (July 2001). “Quantitative in vivo measurement of glutathione in Arabidopsis cells”. 《The Plant Journal》 27 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01071.x. PMID 11489184.

- ↑ Sebastià J, Cristòfol R, Martín M, Rodríguez-Farré E, Sanfeliu C (January 2003). “Evaluation of fluorescent dyes for measuring intracellular glutathione content in primary cultures of human neurons and neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y”. 《Cytometry. Part A》 51 (1): 16–25. doi:10.1002/cyto.a.10003. PMID 12500301.

- ↑ Lantz RC, Lemus R, Lange RW, Karol MH (April 2001). “Rapid reduction of intracellular glutathione in human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to occupational levels of toluene diisocyanate”. 《Toxicological Sciences》 (영어) 60 (2): 348–55. doi:10.1093/toxsci/60.2.348. PMID 11248147.

- ↑ Jiang X, Yu Y, Chen J, Zhao M, Chen H, Song X, Matzuk AJ, Carroll SL, Tan X, Sizovs A, Cheng N, Wang MC, Wang J (March 2015). “Quantitative imaging of glutathione in live cells using a reversible reaction-based ratiometric fluorescent probe”. 《ACS Chemical Biology》 10 (3): 864–74. doi:10.1021/cb500986w. PMC 4371605. PMID 25531746.

- ↑ Jiang X, Chen J, Bajić A, Zhang C, Song X, Carroll SL, Cai ZL, Tang M, Xue M, Cheng N, Schaaf CP, Li F, MacKenzie KR, Ferreon AC, Xia F, Wang MC, Maletić-Savatić M, Wang J (July 2017). “Quantitative imaging of glutathione”. 《Nature Communications》 8: 16087. doi:10.1038/ncomms16087. PMC 5511354. PMID 28703127.

- ↑ Chen J, Jiang X, Zhang C, MacKenzie KR, Stossi F, Palzkill T, Wang MC, Wang J (2017). “Reversible Reaction-Based Fluorescent Probe for Real-Time Imaging of Glutathione Dynamics in Mitochondria”. 《ACS Sensors》 2 (9): 1257–1261. doi:10.1021/acssensors.7b00425. PMC 5771714. PMID 28809477.

- ↑ Meyer AJ, Brach T, Marty L, Kreye S, Rouhier N, Jacquot JP, Hell R (December 2007). “Redox-sensitive GFP in Arabidopsis thaliana is a quantitative biosensor for the redox potential of the cellular glutathione redox buffer”. 《The Plant Journal》 52 (5): 973–86. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03280.x. PMID 17892447.

- ↑ Maulucci G, Labate V, Mele M, Panieri E, Arcovito G, Galeotti T, Østergaard H, Winther JR, De Spirito M, Pani G (October 2008). “High-resolution imaging of redox signaling in live cells through an oxidation-sensitive yellow fluorescent protein”. 《Science Signaling》 1 (43): pl3. doi:10.1126/scisignal.143pl3. PMID 18957692.

- ↑ Giustarini D, Dalle-Donne I, Milzani A, Fanti P, Rossi R (September 2013). “Analysis of GSH and GSSG after derivatization with N-ethylmaleimide”. 《Nature Protocols》 8 (9): 1660–9. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.095. PMID 23928499.

- ↑ Schwarzländer M, Dick T, Meyer AJ, Morgan B (April 2016). “Dissecting Redox Biology Using Fluorescent Protein Sensors”. 《Antioxidants & Redox Signaling》 24 (13): 680–712. doi:10.1089/ars.2015.6266. PMID 25867539.

- ↑ Farkas E, Buglyó P (2017). 〈Chapter 8. Lead(II) Complexes of Amino Acids, Peptides, and Other Related Ligands of Biological Interest〉. Astrid S, Helmut S, Sigel RK. 《Lead: Its Effects on Environment and Health》. Metal Ions in Life Sciences 17. de Gruyter. 201–240쪽. doi:10.1515/9783110434330-008. ISBN 9783110434330. PMID 28731301.

- ↑ Balendiran GK, Dabur R, Fraser D (2004). “The role of glutathione in cancer”. 《Cell Biochemistry and Function》 22 (6): 343–52. doi:10.1002/cbf.1149. PMID 15386533.

- ↑ Visca A, Bishop CT, Hilton SC, Hudson VM (2008). “Improvement in clinical markers in CF patients using a reduced glutathione regimen: An uncontrolled, observational study”. 《Journal of Cystic Fibrosis》 7 (5): 433–6. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2008.03.006. PMID 18499536.

- ↑ Bishop C, Hudson VM, Hilton SC, Wilde C (January 2005). “A pilot study of the effect of inhaled buffered reduced glutathione on the clinical status of patients with cystic fibrosis”. 《Chest》 127 (1): 308–17. doi:10.1378/chest.127.1.308. PMID 15653998.

- ↑ Mandal PK, Tripathi M, Sugunan S (January 2012). “Brain oxidative stress: detection and mapping of anti-oxidant marker 'Glutathione' in different brain regions of healthy male/female, MCI and Alzheimer patients using non-invasive magnetic resonance spectroscopy”. 《Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications》 417 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.047. PMID 22120629.

- ↑ Mandal PK, Saharan, S, Tripathi M, Murari G (October 2015). “Brain Glutathione Levels – A Novel Biomarker for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease”. 《Biological Psychiatry》 78 (10): 702–710. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.005. PMID 26003861.

- ↑ Rigaud J, Cheynier V, Souquet JM, Moutounet M (1991). “Influence of must composition on phenolic oxidation kinetics”. 《Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture》 57 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740570107.

- ↑ Vallverdú-Queralt A, Verbaere A, Meudec E, Cheynier V, Sommerer N (January 2015). “Straightforward method to quantify GSH, GSSG, GRP, and hydroxycinnamic acids in wines by UPLC-MRM-MS”. 《Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry》 63 (1): 142–9. doi:10.1021/jf504383g. PMID 25457918.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Malathi, M; Thappa, DM (2013). “Systemic skin whitening/lightening agents: what is the evidence?”. 《Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology》 79 (6): 842–6. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.120752. PMID 24177629.

- ↑ Dilokthornsakul, W; Dhippayom, T; Dilokthornsakul, P (June 2019). “The clinical effect of glutathione on skin color and other related skin conditions: A systematic review.”. 《Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology》 18 (3): 728–737. doi:10.1111/jocd.12910. PMID 30895708.

- ↑ Sonthalia, Sidharth; Daulatabad, Deepashree; Sarkar, Rashmi (2016). “Glutathione as a skin whitening agent: Facts, myths, evidence and controversies”. 《Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol.》 82 (3): 262–72. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.179088. PMID 27088927.

더 읽을거리[편집]

- Bilinsky LM, Reed MC, Nijhout HF (July 2015). “The role of skeletal muscle in liver glutathione metabolism during acetaminophen overdose”. 《Journal of Theoretical Biology》 376: 118–33. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.04.006. PMC 4431659. PMID 25890031. 요약문 – ALN Magazine (2015년 6월 24일).

- Drevet JR (May 2006). “The antioxidant glutathione peroxidase family and spermatozoa: a complex story”. 《Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology》 250 (1–2): 70–9. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.027. PMID 16427183.

- Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND (March 2004). “Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health”. 《The Journal of Nutrition》 134 (3): 489–92. doi:10.1093/jn/134.3.489. PMID 14988435.

외부 링크[편집]

- Glutathione bound to proteins in the PDB

- Risk Factors