사용자:Evraziskykr/연습장

Россия является многонациональным государством, что отражено в её Конституции. На территории России проживает более 190 народов, в число которых входят не только коренные малые и автохтонные народы страны. В 2010 году русские составили 80,9 % или 111,0 млн из 137,2 млн указавших свою национальную принадлежность, представители других национальностей — 19,1 % или 26,2 млн чел.; численность лиц, не указавших свою национальность, составила 5,6 млн чел. (или 3,9 % от 142,9 млн жителей страны в целом). В 2002 году русские составляли 80,6 % или около 115,9 млн из 143,7 млн указавших свою национальную принадлежность, представители других национальностей — 19,4 % или 27,8 млн чел.; численность лиц, не указавших свою национальность, составила 1,5 млн чел. (или 1,0 % от 145,2 млн жителей страны в целом). Россия — это единственная страна СНГ, где доля титульной нации не возрастает[1].

Россия является многонациональным государством, что отражено в её Конституции. На территории России проживает более 190 народов, в число которых входят не только коренные малые и автохтонные народы страны. В 2010 году русские составили 80,9 % или 111,0 млн из 137,2 млн указавших свою национальную принадлежность, представители других национальностей — 19,1 % или 26,2 млн чел.; численность лиц, не указавших свою национальность, составила 5,6 млн чел. (или 3,9 % от 142,9 млн жителей страны в целом). В 2002 году русские составляли 80,6 % или около 115,9 млн из 143,7 млн указавших свою национальную принадлежность, представители других национальностей — 19,4 % или 27,8 млн чел.; численность лиц, не указавших свою национальность, составила 1,5 млн чел. (или 1,0 % от 145,2 млн жителей страны в целом). Россия — это единственная страна СНГ, где доля титульной нации не возрастает[1].

Динамика и прирост численности в 2002—2010 гг[편집]

В данной таблице приведён национальный состав населения России по переписям 2002 и 2010 годов и изменение (прирост или убыль) за этот период в численном и процентном выражении.

| № | Народность | в том числе[2][3] | Чис- лен- ность чел. 2002 [4][5][6] |

% от всего насе- ления |

% от ука- зав- ших на- цио- наль- ность |

Чис- лен- ность чел. 2010 [2][3] |

% от всего насе- ления |

% от ука- зав- ших на- цио- наль- ность |

Абс. прирост (убыль) чел. 2002—2010 |

При- рост (убыль) % 2002—2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Русские | казаки, поморы | 115889107 | 79,83 % | 80,64 % | 111016896 | 77,71 % | 80,90 % | −4872211 | −4,20 % |

| 2 | Татары | кряшены, сибирские татары, мишари, астраханские татары | 5554601 | 3,83 % | 3,87 % | 5310649 | 3,72 % | 3,87 % | −243952 | −4,39 % |

| 3 | Украинцы[7] | 2942961 | 2,03 % | 2,05 % | 1927988 | 1,35 % | 1,41 % | −1014973 | −34,49 % | |

| 4 | Башкиры | 1673389 | 1,15 % | 1,16 % | 1584554 | 1,11 % | 1,16 % | −88835 | −5,31 % | |

| 5 | Чуваши | 1637094 | 1,13 % | 1,14 % | 1435872 | 1,01 % | 1,05 % | −201222 | −12,29 % | |

| 6 | Чеченцы | чеченцы-аккинцы | 1360253 | 0,94 % | 0,95 % | 1431360 | 1,00 % | 1,04 % | 71107 | 5,23 % |

| 7 | Армяне | черкесогаи | 1130491 | 0,78 % | 0,79 % | 1182388 | 0,83 % | 0,86 % | 51897 | 4,59 % |

| 8 | Аварцы | андийцы, дидойцы (цезы) и другие андо-цезские народности[8] и арчинцы | 814473 | 0,56 % | 0,57 % | 912090 | 0,64 % | 0,67 % | 97617 | 11,99 % |

| 9 | Мордва | мордва-мокша, мордва-эрзя | 843350 | 0,58 % | 0,59 % | 744237 | 0,52 % | 0,54 % | −99113 | −11,75 % |

| 10 | Казахи | 653962 | 0,45 % | 0,46 % | 647732 | 0,45 % | 0,47 % | −6230 | −0,95 % | |

| 11 | Азербайджанцы | 621840 | 0,43 % | 0,43 % | 603070 | 0,42 % | 0,44 % | −18770 | −3,02 % | |

| 12 | Даргинцы | кайтагцы, кубачинцы | 510156 | 0,35 % | 0,35 % | 589386 | 0,41 % | 0,43 % | 79230 | 15,53 % |

| 13 | Удмурты | 636906 | 0,44 % | 0,44 % | 552299 | 0,39 % | 0,40 % | −84607 | −13,28 % | |

| 14 | Марийцы | горные марийцы, лугово-восточные марийцы, северо-западные марийцы | 604298 | 0,42 % | 0,42 % | 547605 | 0,38 % | 0,40 % | −56693 | −9,38 % |

| 15 | Осетины | дигорон (дигорцы), ирон (иронцы) | 514875 | 0,36 % | 0,36 % | 528515 | 0,37 % | 0,39 % | 13640 | 2,65 % |

| 16 | Белорусы | 807970 | 0,56 % | 0,56 % | 521443 | 0,37 % | 0,38 % | −286527 | −35,46 % | |

| 17 | Кабардинцы | 519958 | 0,36 % | 0,36 % | 516826 | 0,36 % | 0,38 % | −3132 | −0,60 % | |

| 18 | Кумыки | 422409 | 0,29 % | 0,29 % | 503060 | 0,35 % | 0,37 % | 80651 | 19,09 % | |

| 19 | Якуты | 443852 | 0,31 % | 0,31 % | 478085 | 0,34 % | 0,35 % | 34233 | 7,71 % | |

| 20 | Лезгины | 411535 | 0,28 % | 0,29 % | 473722 | 0,33 % | 0,35 % | 62187 | 15,11 % | |

| 21 | Буряты | 445175 | 0,31 % | 0,31 % | 461389 | 0,32 % | 0,34 % | 16214 | 3,64 % | |

| 22 | Ингуши | 413016 | 0,29 % | 0,29 % | 444833 | 0,31 % | 0,32 % | 31817 | 7,70 % | |

| 23 | Немцы | меннониты | 597212 | 0,41 % | 0,42 % | 394138 | 0,28 % | 0,29 % | −203074 | −34,00 % |

| 24 | Узбеки | 122916 | 0,09 % | 0,09 % | 289862 | 0,20 % | 0,21 % | 166946 | 135,82 % | |

| 25 | Тувинцы | тоджинцы | 243442 | 0,17 % | 0,17 % | 263934 | 0,19 % | 0,19 % | 20492 | 8,42 % |

| 26 | Коми | коми-ижемцы | 293406 | 0,20 % | 0,20 % | 228235 | 0,16 % | 0,17 % | −65171 | −22,21 % |

| 27 | Карачаевцы | 192182 | 0,13 % | 0,13 % | 218403 | 0,15 % | 0,16 % | 26221 | 13,64 % | |

| 28 | Цыгане | 182766 | 0,13 % | 0,13 % | 204958 | 0,14 % | 0,15 % | 22192 | 12,14 % | |

| 29 | Таджики | 120136 | 0,08 % | 0,08 % | 200303 | 0,14 % | 0,15 % | 80167 | 66,73 % | |

| 30 | Калмыки | 173996 | 0,12 % | 0,12 % | 183372 | 0,13 % | 0,13 % | 9376 | 5,39 % | |

| 31 | Лакцы | 156545 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | 178630 | 0,13 % | 0,13 % | 22085 | 14,11 % | |

| 32 | Грузины | аджарцы, ингилойцы, лазы, мегрелы, сваны | 197934 | 0,14 % | 0,14 % | 157803 | 0,11 % | 0,12 % | −40131 | −20,27 % |

| 33 | Евреи | 229938 | 0,16 % | 0,16 % | 156801 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | −73137 | −31,81 % | |

| 34 | Молдаване | 172330 | 0,12 % | 0,12 % | 156400 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | −15930 | −9,24 % | |

| 35 | Корейцы | 148556 | 0,10 % | 0,10 % | 153156 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | 4600 | 3,10 % | |

| 36 | Табасараны | 131785 | 0,09 % | 0,09 % | 146360 | 0,10 % | 0,11 % | 14575 | 11,06 % | |

| 37 | Адыгейцы | 128528 | 0,09 % | 0,09 % | 124835 | 0,09 % | 0,09 % | −3693 | −2,87 % | |

| 38 | Балкарцы | 108426 | 0,08 % | 0,08 % | 112924 | 0,08 % | 0,08 % | 4498 | 4,15 % | |

| 39 | Турки | 92415 | 0,06 % | 0,06 % | 105058 | 0,07 % | 0,08 % | 12643 | 13,68 % | |

| 40 | Ногайцы | карагаши | 90666 | 0,06 % | 0,06 % | 103660 | 0,07 % | 0,08 % | 12994 | 14,33 % |

| 41 | Киргизы | 31808 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 103422 | 0,07 % | 0,08 % | 71614 | 225,14 % | |

| 42 | Коми-пермяки | 125235 | 0,09 % | 0,09 % | 94456 | 0,07 % | 0,07 % | −30779 | −24,58 % | |

| 43 | Греки | греки-урумы | 97827 | 0,07 % | 0,07 % | 85640 | 0,06 % | 0,06 % | −12187 | −12,46 % |

| 44 | Алтайцы[9] | теленгиты, тубалары, челканцы | 72058 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | 74238 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | 2180 | 3,03 % |

| 45 | Черкесы | 60517 | 0,04 % | 0,04 % | 73184 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | 12667 | 20,93 % | |

| 46 | Хакасы | 75622 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | 72959 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | −2663 | −3,52 % | |

| 47 | Казаки[10] | 140028 | 0,10 % | 0,10 % | 67573 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | −72455 | −51,74 % | |

| 48 | Карелы | 93344 | 0,06 % | 0,06 % | 60815 | 0,04 % | 0,04 % | −32529 | −34,85 % | |

| 49 | Мордва-эрзя[11] | 84407 | 0,06 % | 0,06 % | 57008 | 0,04 % | 0,04 % | −27399 | −32,46 % | |

| 50 | Поляки | 73001 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | 47125 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | −25876 | −35,45 % | |

| 51 | Ненцы | 41302 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 44640 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 3338 | 8,08 % | |

| 52 | Абазины | 37942 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 43341 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 5399 | 14,23 % | |

| 53 | Езиды | 31273 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 40586 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 9313 | 29,78 % | |

| 54 | Эвенки | 35527 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 38396 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 2869 | 8,08 % | |

| 55 | Туркмены | 33053 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 36885 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 3832 | 11,59 % | |

| 56 | Рутульцы | 29929 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 35240 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 5311 | 17,75 % | |

| 57 | Кряшены[12] | 24668 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 34822 | 0,02 % | 0,03 % | 10154 | 41,16 % | |

| 58 | Агулы | 28297 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 34160 | 0,02 % | 0,03 % | 5863 | 20,72 % | |

| 59 | Литовцы | 45569 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 31377 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | −14192 | −31,14 % | |

| 60 | Ханты | 28678 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 30943 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 2265 | 7,90 % | |

| 61 | Китайцы | 34577 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 28943 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | −5634 | −16,29 % | |

| 62 | Болгары | 31965 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 24038 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | −7927 | −24,80 % | |

| 63 | Горные марийцы[13] | 18515 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 23559 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 5044 | 27,24 % | |

| 64 | Курды | 19607 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 23232 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 3625 | 18,49 % | |

| 65 | Эвены | 19071 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 21830 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 2759 | 14,47 % | |

| 66 | Финны | финны-ингерманландцы | 34050 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 20267 | 0,01 % | 0,02 % | −13783 | −40,48 % |

| 67 | Латыши | 28520 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 18979 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −9541 | −33,45 % | |

| 68 | Эстонцы | 28113 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 17875 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −10238 | −36,42 % | |

| 69 | Чукчи | 15767 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 15908 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 141 | 0,89 % | |

| 70 | Вьетнамцы | 26206 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 13954 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −12252 | −46,75 % | |

| 71 | Гагаузы | 12210 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 13690 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 1480 | 12,12 % | |

| 72 | Шорцы | 13975 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 12888 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −1087 | −7,78 % | |

| 73 | Цахуры | 10366 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 12769 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 2403 | 23,18 % | |

| 74 | Манси | 11432 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 12269 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 837 | 7,32 % | |

| 75 | Нанайцы | 12160 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 12003 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −157 | −1,29 % | |

| 76 | Андийцы[14] | 21808 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | 11789 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −10019 | −45,94 % | |

| 77 | Дидойцы[15] | 15256 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 11683 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −3573 | −23,42 % | |

| 78 | Абхазы | 11366 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 11249 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −117 | −1,03 % | |

| 79 | Ассирийцы | 13649 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 11084 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −2565 | −18,79 % | |

| 80 | Арабы | алжирцы, арабы ОАЭ, бахрейнцы, египтяне, иорданцы, иракцы, йеменцы, катарцы, кувейтцы, ливанцы, ливийцы, мавританцы, марокканцы, оманцы, палестинцы, саудовцы, сирийцы, суданцы, тунисцы | 10630 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 9583 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −1047 | −9,85 % |

| 81 | Нагайбаки | 9600 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 8148 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −1452 | −15,13 % | |

| 82 | Коряки | 8743 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 7953 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −790 | −9,04 % | |

| 83 | Ахвахцы[16] | 6376 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 7930 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 1554 | 24,37 % | |

| 84 | Долганы | 7261 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 7885 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 624 | 8,59 % | |

| 85 | Сибирские татары[17] | 9611 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 6779 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | −2832 | −29,47 % | |

| 86 | Коми-ижемцы[18] | 15607 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 6420 | 0,00 % | 0,01 % | −9187 | −58,86 % | |

| 87 | Бежтинцы[19] | 6198 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 5958 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −240 | −3,87 % | |

| 88 | Вепсы | 8240 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 5936 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −2304 | −27,96 % | |

| 89 | Пуштуны (афганцы) | 9800 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | 5350 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −4450 | −45,41 % | |

| 90 | Турки-месхетинцы | 3257 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4825 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1568 | 48,14 % | |

| 91 | Каратинцы[20] | 6052 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4787 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −1265 | −20,90 % | |

| 92 | Мордва-мокша[21] | 49624 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 4767 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −44857 | −90,39 % | |

| 93 | Нивхи | 5162 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4652 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −510 | −9,88 % | |

| 94 | Удины | 3721 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4267 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 546 | 14,67 % | |

| 95 | Индийцы (хинди) | 4980 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4058 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −922 | −18,51 % | |

| 96 | Шапсуги | 3231 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3882 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 651 | 20,15 % | |

| 97 | Теленгиты[22] | 2399 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3712 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1313 | 54,73 % | |

| 98 | Персы | 3821 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3696 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −125 | −3,27 % | |

| 99 | Уйгуры | 2867 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3696 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 829 | 28,92 % | |

| 100 | Селькупы | 4249 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3649 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −600 | −14,12 % | |

| 101 | Сойоты | 2769 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3608 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 839 | 30,30 % | |

| 102 | Сербы | 4156 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3510 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −646 | −15,54 % | |

| 103 | Ботлихцы[23] | 16 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3508 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3492 | 21825,00 % | |

| 104 | Румыны | 5308 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3201 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −2107 | −39,69 % | |

| 105 | Ительмены | 3180 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 3193 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 13 | 0,41 % | |

| 106 | Поморы[24] | 6571 | 0,01 % | 0,00 % | 3113 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −3458 | −52,63 % | |

| 107 | Монголы | 2656 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2986 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 330 | 12,42 % | |

| 108 | Кумандинцы | 3114 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2892 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −222 | −7,13 % | |

| 109 | Венгры | 3768 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2781 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −987 | −26,19 % | |

| 110 | Ульчи | 2913 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2765 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −148 | −5,08 % | |

| 111 | Телеуты | 2650 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2643 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −7 | −0,26 % | |

| 112 | Талыши | 2548 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2529 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −19 | −0,75 % | |

| 113 | Крымские татары | 4131 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2449 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −1682 | −40,72 % | |

| 114 | Бесермяне | 3122 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2201 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −921 | −29,50 % | |

| 115 | Хемшилы | 1542 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2047 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 505 | 32,75 % | |

| 116 | Тубалары[25] | 1565 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1965 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 400 | 25,56 % | |

| 117 | Камчадалы | 2293 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1927 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −366 | −15,96 % | |

| 118 | Чехи | 2904 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1898 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −1006 | −34,64 % | |

| 119 | Тоджинцы (тыва-тоджинцы)[26] | 4442 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1858 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −2584 | −58,17 % | |

| 120 | Саамы | 1991 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1771 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −220 | −11,05 % | |

| 121 | Эскимосы | 1750 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1738 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −12 | −0,69 % | |

| 122 | Дунгане | 801 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1651 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 850 | 106,12 % | |

| 123 | Юкагиры | 1509 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1603 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 94 | 6,23 % | |

| 124 | Таты | 2303 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1585 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −718 | −31,18 % | |

| 125 | Американцы США | 1275 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1572 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 297 | 23,29 % | |

| 126 | Удэгейцы | 1657 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1496 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −161 | −9,72 % | |

| 127 | Французы | 819 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1475 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 656 | 80,10 % | |

| 128 | Каракалпаки | 1609 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1466 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −143 | −8,89 % | |

| 129 | Итальянцы | 862 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1370 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 508 | 58,93 % | |

| 130 | Кеты | 1494 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1219 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −275 | −18,41 % | |

| 131 | Челканцы[27] | 855 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1181 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 326 | 38,13 % | |

| 132 | Испанцы | 1547 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1162 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −385 | −24,89 % | |

| 133 | Латгальцы[28] | 1622 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1089 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −533 | −32,86 % | |

| 134 | Чуванцы | 1087 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1002 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −85 | −7,82 % | |

| 135 | Британцы | англичане, шотландцы и др. | 529 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 950 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 421 | 79,58 % |

| 136 | Гунзибцы[29] | 998 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 918 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −80 | −8,02 % | |

| 137 | Японцы | 835 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 888 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 53 | 6,35 % | |

| 138 | Нганасаны | 834 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 862 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 28 | 3,36 % | |

| 139 | Мишари[30] | 557 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 786 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 229 | 41,11 % | |

| 140 | Горские евреи (таты-иудаисты) | 3394 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 762 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −2632 | −77,55 % | |

| 141 | Тофалары | 837 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 762 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −75 | −8,96 % | |

| 142 | Кубинцы | 707 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 676 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −31 | −4,38 % | |

| 143 | Тиндалы[31] | 44 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 635 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 591 | 1343,18 % | |

| 144 | Мегрелы[32] | 433 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 600 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 167 | 38,57 % | |

| 145 | Орочи | 686 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 596 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −90 | −13,12 % | |

| 146 | Хваршины[33] | 128 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 527 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 399 | 311,72 % | |

| 147 | Негидальцы | 567 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 513 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −54 | −9,52 % | |

| 148 | Пакистанцы[34] | пенджабцы, белуджи, синдхи и др. | 81 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 507 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 426 | 525,93 % |

| 149 | Алеуты | 540 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 482 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −58 | −10,74 % | |

| 150 | Гинухцы[35] | 531 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 443 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −88 | −16,57 % | |

| 151 | Финны-ингерманландцы[36] | 314 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 441 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 127 | 40,45 % | |

| 152 | Годоберинцы[37] | 39 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 427 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 388 | 994,87 % | |

| 153 | Бангладешцы | бенгальцы | 489 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 392 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −97 | −19,84 % |

| 154 | Памирцы | рушанцы, баджуйцы, шугнанцы и др. | 62 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 363 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 301 | 485,48 % |

| 155 | Чулымцы | 656 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 355 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −301 | −45,88 % | |

| 156 | Ланкийцы | сингалы, тамилы | 0 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 326 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 326 | |

| 157 | Македонцы | 0 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 325 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 325 | ||

| 158 | Словаки | 568 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 324 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −244 | −42,96 % | |

| 159 | Хорваты | 412 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 304 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −108 | −26,21 % | |

| 160 | Ульта (ороки) | 346 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 295 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −51 | −14,74 % | |

| 161 | Тазы (удэ) | 276 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 274 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −2 | −0,72 % | |

| 162 | Ижорцы | 327 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 266 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −61 | −18,65 % | |

| 163 | Боснийцы | 0 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 256 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 256 | ||

| 164 | Энцы | 237 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 227 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −10 | −4,22 % | |

| 165 | Русины | 97 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 225 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 128 | 131,96 % | |

| 166 | Осетины-дигорцы[38] | 607 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 223 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −384 | −63,26 % | |

| 167 | Лугово-восточные марийцы[39] | 56119 | 0,04 % | 0,04 % | 218 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −55901 | −99,61 % | |

| 168 | Сету[40] | 197 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 214 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 17 | 8,63 % | |

| 169 | Аджарцы[41] | 252 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 211 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −41 | −16,27 % | |

| 170 | Караимы | 366 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 205 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −161 | −43,99 % | |

| 171 | Черногорцы | 131 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 181 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 50 | 38,17 % | |

| 172 | Лазы[42] | 221 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 160 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −61 | −27,60 % | |

| 173 | Кубачинцы[43] | 88 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 120 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 32 | 36,36 % | |

| 174 | Ингилойцы[44] | 63 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 98 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 35 | 55,56 % | |

| 175 | Крымчаки | 157 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 90 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −67 | −42,68 % | |

| 176 | Грузинские евреи | 53 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 78 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 25 | 47,17 % | |

| 177 | Чеченцы-аккинцы[45] | 218 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 76 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −142 | −65,14 % | |

| 178 | Водь | 73 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 64 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −9 | −12,33 % | |

| 179 | Среднеазиатские цыгане | 486 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 49 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −437 | −89,92 % | |

| 180 | Осетины-иронцы[46] | 97 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 48 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −49 | −50,52 % | |

| 181 | Сваны[47] | 41 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 45 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4 | 9,76 % | |

| 182 | Курманч (курмандж)[48] | 1 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 42 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 41 | 4100,00 % | |

| 183 | Среднеазиатские евреи | 54 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 32 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −22 | −40,74 % | |

| 184 | Чамалалы[49] | 12 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 24 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 12 | 100,00 % | |

| 185 | Карагаши[50] | 21 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 16 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −5 | −23,81 % | |

| 186 | Арчинцы[51] | 89 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 12 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −77 | −86,52 % | |

| 187 | Кайтагцы[52] | 5 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 7 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 2 | 40,00 % | |

| 188 | Астраханские татары[53] | 2003 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 7 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −1996 | −99,65 % | |

| 189 | Черкесогаи[54] | 6 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 6 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 0 | 0,00 % | |

| 190 | Багулалы[55] | 40 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 5 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −35 | −87,50 % | |

| 191 | Кереки | 8 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −4 | −50,00 % | |

| 192 | Меннониты[56] | 39 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 4 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −35 | −89,74 % | |

| 193 | Греки-урумы[57] | 54 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −53 | −98,15 % | |

| 194 | Юги[58] | 19 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | 1 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | −18 | −94,74 % | |

| … | прочие[59] | 41986 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | 66938 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | 24952 | 59,43 % | |

| … | итого лиц, указавших национальность | 143705980 | 98,99 % | 100,00 % | 137227107 | 96,06 % | 100,00 % | −6478873 | −4,51 % | |

| … | не указавшие национальность (2002, 2010), включая лиц, по которым сведения получены из административных источников (2010) |

1460751 | 1,01 % | 5629429 | 3,94 % | 4168678 | 285,38 % | |||

| … | ВСЕГО, РФ[60] | 145166731 | 100,00 % | 142856536 | 100,00 % | −2310195 | −1,59 % |

-

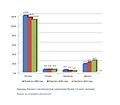

Народы России с численностью населения более 1 млн. человек по данным переписи населения 2010 года

-

Народы России с численностью населения более 1,9 млн. человек

-

Народы России с численностью населения от 0,5 млн. (на 2010 год) до 1,8 млн. человек

С 1989 по 2002 год увеличилась численность армян (на 212 %), чеченцев (на 50 %) и башкир. Численность татар почти не изменилась. Незначительно сократилась численность чувашей[61].

В 2002—2010 годах, за редким исключением, численность населения большинства «европейских» народов, проживающих на территории Российской Федерации, уменьшается, а «азиатских» — увеличивается. Так, среди народов России с количеством населения свыше 30 000 человек максимальный прирост наблюдался:

А максимальная убыль среди народов России с количеством населения свыше 30 000 человек наблюдалась:

Народы и этногруппы России по данным Всероссийской переписи 2010 года[편집]

| № | Народность | в том числе[2][3] | Численность чел.[2][3] |

% от всего населения |

% от указавших национальность |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Русские | казаки, поморы | 111 016 897 | 77,71 % | 80,90 % |

| 2 | Татары | кряшены, мишари, сибирские татары, астраханские татары | 5 310 649 | 3,72 % | 3,87 % |

| 3 | Украинцы[62] | 1 927 988 | 1,35 % | 1,40 % | |

| 4 | Башкиры | 1 584 554 | 1,11 % | 1,15 % | |

| 5 | Чуваши | 1 435 872 | 1,01 % | 1,05 % | |

| 6 | Чеченцы | чеченцы-аккинцы | 1 431 360 | 1,00 % | 1,04 % |

| 7 | Армяне | черкесогаи | 1 182 388 | 0,83 % | 0,86 % |

| 8 | Аварцы | андийцы, дидойцы (цезы) и другие андо-цезские народности[8] и арчинцы | 912 090 | 0,64 % | 0,66 % |

| 9 | Мордва | мордва-мокша, мордва-эрзя | 744 237 | 0,52 % | 0,54 % |

| 10 | Казахи | 647 732 | 0,45 % | 0,47 % | |

| 11 | Азербайджанцы | 603 070 | 0,42 % | 0,44 % | |

| 12 | Даргинцы | кайтагцы, кубачинцы | 589 386 | 0,41 % | 0,43 % |

| 13 | Удмурты | 552 299 | 0,39 % | 0,40 % | |

| 14 | Марийцы | горные марийцы, лугово-восточные марийцы | 547 605 | 0,38 % | 0,40 % |

| 15 | Осетины | дигорон (дигорцы), ирон (иронцы) | 528 515 | 0,37 % | 0,39 % |

| 16 | Белорусы | 521 443 | 0,37 % | 0,38 % | |

| 17 | Кабардинцы | 516 826 | 0,36 % | 0,38 % | |

| 18 | Кумыки | 503 060 | 0,35 % | 0,37 % | |

| 19 | Якуты | 478 085 | 0,33 % | 0,35 % | |

| 20 | Лезгины | 473 722 | 0,33 % | 0,35 % | |

| 21 | Буряты | 461 389 | 0,32 % | 0,34 % | |

| 22 | Ингуши | 444 833 | 0,31 % | 0,32 % | |

| 23 | Немцы | меннониты | 394 138 | 0,28 % | 0,29 % |

| 24 | Узбеки | 289 862 | 0,20 % | 0,21 % | |

| 25 | Тувинцы | тоджинцы | 263 934 | 0,18 % | 0,19 % |

| 26 | Коми | коми-ижемцы | 228 235 | 0,16 % | 0,17 % |

| 27 | Карачаевцы | 218 403 | 0,15 % | 0,16 % | |

| 28 | Цыгане | 204 958 | 0,14 % | 0,15 % | |

| 29 | Таджики | 200 303 | 0,14 % | 0,15 % | |

| 30 | Калмыки | 183 372 | 0,13 % | 0,13 % | |

| 31 | Лакцы | 178 630 | 0,13 % | 0,13 % | |

| 32 | Грузины | аджарцы, ингилойцы, лазы, мегрелы, сваны | 157 803 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % |

| 33 | Евреи | 156 801 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | |

| 34 | Молдаване | 156 400 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | |

| 35 | Корейцы | 153 156 | 0,11 % | 0,11 % | |

| 36 | Табасараны | 146 360 | 0,10 % | 0,11 % | |

| 37 | Адыгейцы | 124 835 | 0,09 % | 0,09 % | |

| 38 | Балкарцы | 112 924 | 0,08 % | 0,08 % | |

| 39 | Турки | 105 058 | 0,07 % | 0,08 % | |

| 40 | Ногайцы | карагаши | 103 660 | 0,07 % | 0,08 % |

| 41 | Киргизы | 103 422 | 0,07 % | 0,08 % | |

| 42 | Коми-пермяки | 94 456 | 0,07 % | 0,07 % | |

| 43 | Греки | греки-урумы | 85 640 | 0,06 % | 0,06 % |

| 44 | Алтайцы | теленгиты, тубалары, челканцы | 74 238 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % |

| 45 | Черкесы | 73 184 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | |

| 46 | Хакасы | 72 959 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | |

| 47 | Казаки[63] | 67 573 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | |

| 48 | Карелы | 60 815 | 0,04 % | 0,04 % | |

| 49 | Мордва-эрзя[64] | 57 008 | 0,04 % | 0,04 % | |

| 50 | Поляки | 47 125 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | |

| 51 | Ненцы | 44 640 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | |

| 52 | Абазины | 43 341 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | |

| 53 | Езиды | 40 586 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | |

| 54 | Эвенки | 38 396 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | |

| 55 | Туркмены | 36 885 | 0,03 % | 0,03 % | |

| 56 | Рутульцы | 35 240 | 0,02 % | 0,03 % | |

| 57 | Кряшены[65] | 34 822 | 0,02 % | 0,03 % | |

| 58 | Агулы | 34 160 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 59 | Литовцы | 31 377 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 60 | Ханты | 30 943 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 61 | Китайцы | 28 943 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 62 | Болгары | 24 038 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 63 | Горные марийцы[66] | 23 559 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 64 | Курды | 23 232 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 65 | Эвены | 21 830 | 0,02 % | 0,02 % | |

| 66 | Финны | финны-ингерманландцы | 20 267 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % |

| 67 | Латыши | 18 979 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 68 | Эстонцы | 17 875 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 69 | Чукчи | 15 908 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 70 | Вьетнамцы | 13 954 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 71 | Гагаузы | 13 690 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 72 | Шорцы | 12 888 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 73 | Цахуры | 12 769 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 74 | Манси | 12 269 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 75 | Нанайцы | 12 003 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 76 | Андийцы[67] | 11 789 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 77 | Дидойцы[68] | 11 683 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 78 | Абхазы | 11 249 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 79 | Ассирийцы | 11 084 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 80 | Арабы | алжирцы, арабы ОАЭ, бахрейнцы, египтяне, иорданцы, иракцы, йеменцы, катарцы, кувейтцы, ливанцы, ливийцы, мавританцы, марокканцы, оманцы, палестинцы, саудовцы, сирийцы, суданцы, тунисцы | 9 583 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % |

| 81 | Нагайбаки | 8 148 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 82 | Коряки | 7 953 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 83 | Ахвахцы[69] | 7 930 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 84 | Долганы | 7 885 | 0,01 % | 0,01 % | |

| 85 | Сибирские татары[70] | 6 779 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 86 | Коми-ижемцы[71] | 6 420 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 87 | Бежтинцы[72] | 5 958 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 88 | Вепсы | 5 936 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 89 | Пуштуны (афганцы) | 5 350 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 90 | Турки-месхетинцы | 4 825 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 91 | Каратинцы[73] | 4 787 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 92 | Мордва-мокша[74] | 4 767 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 93 | Нивхи | 4 652 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 94 | Удины | 4 267 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 95 | Индийцы (хинди) | 4 058 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 96 | Шапсуги | 3 882 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 97 | Теленгиты[22] | 3 712 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 98 | Персы | 3 696 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 99 | Уйгуры | 3 696 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 100 | Селькупы | 3 649 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 101 | Сойоты | 3 608 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 102 | Сербы | 3 510 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 103 | Ботлихцы[75] | 3 508 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 104 | Румыны | 3 201 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 105 | Ительмены | 3 193 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 106 | Поморы[76] | 3 113 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 107 | Монголы | 2 986 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 108 | Кумандинцы | 2 892 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 109 | Венгры | 2 781 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 110 | Ульчи | 2 765 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 111 | Телеуты | 2 643 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 112 | Талыши | 2 529 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 113 | Крымские татары | 2 449 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 114 | Бесермяне | 2 201 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 115 | Хемшилы | 2 047 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 116 | Тубалары[25] | 1 965 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 117 | Камчадалы | 1 927 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 118 | Чехи | 1 898 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 119 | Тоджинцы (тыва-тоджинцы)[77] | 1 858 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 120 | Саамы | 1 771 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 121 | Эскимосы | 1 738 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 122 | Дунгане | 1 651 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 123 | Юкагиры | 1 603 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 124 | Таты | 1 585 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 125 | Американцы США | 1 572 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 126 | Удэгейцы | 1 496 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 127 | Французы | 1 475 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 128 | Каракалпаки | 1 466 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 129 | Итальянцы | 1 370 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 130 | Кеты | 1 219 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 131 | Челканцы[27] | 1 181 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 132 | Испанцы | 1 162 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 133 | Латгальцы[78] | 1 089 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 134 | Чуванцы | 1 002 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 135 | Британцы | англичане, шотландцы и др. | 950 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % |

| 136 | Гунзибцы[79] | 918 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 137 | Японцы | 888 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 138 | Нганасаны | 862 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 139 | Мишари[80] | 786 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 140 | Горские евреи (таты-иудаисты) | 762 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 141 | Тофалары | 762 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 142 | Кубинцы | 676 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 143 | Тиндалы[81] | 635 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 144 | Мегрелы[82] | 600 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 145 | Орочи | 596 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 146 | Хваршины[83] | 527 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 147 | Негидальцы | 513 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 148 | Пакистанцы | пенджабцы, белуджи, синдхи и др. | 507 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % |

| 149 | Алеуты | 482 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 150 | Гинухцы[84] | 443 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 151 | Финны-ингерманландцы[85] | 441 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 152 | Годоберинцы[86] | 427 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 153 | Бангладешцы | бенгальцы | 392 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % |

| 154 | Памирцы | рушанцы, баджуйцы, шугнанцы и др. | 363 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % |

| 155 | Чулымцы | 355 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 156 | Ланкийцы | сингалы, тамилы | 326 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % |

| 157 | Македонцы | 325 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 158 | Словаки | 324 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 159 | Хорваты | 304 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 160 | Ульта (ороки) | 295 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 161 | Тазы (удэ) | 274 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 162 | Ижорцы | 266 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 163 | Боснийцы | 256 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 164 | Энцы | 227 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 165 | Русины | 225 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 166 | Осетины-дигорцы[87] | 223 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 167 | Лугово-восточные марийцы[88] | 218 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 168 | Сету[89] | 214 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 169 | Аджарцы[90] | 211 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 170 | Караимы | 205 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 171 | Черногорцы | 181 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 172 | Лазы[91] | 160 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 173 | Кубачинцы[92] | 120 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 174 | Ингилойцы[93] | 98 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 175 | Крымчаки | 90 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 176 | Грузинские евреи | 78 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 177 | Чеченцы-аккинцы[94] | 76 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 178 | Водь | 64 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 179 | Среднеазиатские цыгане | 49 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 180 | Осетины-иронцы[95] | 48 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 181 | Сваны[96] | 45 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 182 | Курманч[97] | 42 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 183 | Среднеазиатские евреи | 32 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 184 | Чамалалы[98] | 24 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 185 | Карагаши[99] | 16 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 186 | Арчинцы[100] | 12 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 187 | Кайтагцы[101] | 7 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 188 | Астраханские татары[102] | 7 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 189 | Черкесогаи[103] | 6 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 190 | Багулалы[104] | 5 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 191 | Кереки | 4 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 192 | Меннониты[105] | 4 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 193 | Греки-урумы[106] | 1 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| 194 | Юги[107] | 1 | 0,00 % | 0,00 % | |

| … | прочие | 66 938 | 0,05 % | 0,05 % | |

| … | итого лиц, указавших национальность | 137 227 107 | 96,06 % | 100,00 % | |

| … | не указавшие национальность, включая лиц, по которым сведения получены из административных источников |

5 629 429 | 3,94 % | ||

| … | ВСЕГО, РФ[60] | 142 856 536 | 100,00 % |

Народы и этногруппы России по данным Всероссийской переписи 2002 года[편집]

| № | Народность | Самоназвания и в том числе[5][6] | Численность чел. [4] |

% от всего населения |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Русские | затундренные крестьяне, индигирщики/русскоустьинцы, каменщики, карымы, кержаки, колымские/колымчане/походчане, ленские старожилы/якутяне, мезенцы, обские старожилы, семейские, ямские; казаки, поморы | 115 889 107 | 79,83 |

| 2 | Татары | казанлы, казанские татары, каринские (нукратские татары, касимовские татары, мещеряки, мишари, мишэр, татар, тептяри с языком татарским, тептяри-татары); кряшены, сибирские татары, астраханские татары | 5 554 601 | 3,83 |

| 3 | Украинцы | буковинцы, верховинцы, гуцулы, казаки с языком украинским | 2 942 974 | 2,03 |

| 4 | Башкиры | башкорт, башкурт, башгирд, казаки с языком башкирским, тептяри-башкиры, тептяри с языком башкирским, мишари-башкиры | 1 673 389 | 1,15 |

| 5 | Чуваши | вирьял, мижерь, чаваш | 1 637 094 | 1,12 |

| 6 | Чеченцы | нохчий, чаан; чеченцы-аккинцы | 1 360 253 | 0,93 |

| 7 | Армяне | гай, донские армяне, крымские армяне, франк, хай, черкесогаи | 1 130 491 | 0,78 |

| 8 | Мордва | каратаи, мордвины, мордовцы; мордва-мокша, мордва-эрзя | 843 350 | 0,58 |

| 9 | Аварцы | аварал, маарулал; андийцы, дидойцы (цезы) и другие андо-цезские народности[8] и арчинцы | 814 473 | 0,56 |

| 10 | Белорусы | беларусы, брещуки, литвины, литвяки | 807 970 | 0,55 |

| 11 | Казахи | адай, аргын, берш, жагайбайлы, жаппас, керей, кыпчак с языком казахским, найман с языком казахским, ногай с языком казахским, степские казахи, табын, тама, торкара, туратинские казахи, уак | 653 962 | 0,45 |

| 12 | Удмурты | вотяки, одморт, одмурт, удморт, укморт, урморт, уртморт | 636 906 | 0,44 |

| 13 | Азербайджанцы | азербайджанлы, азербайджанлылар, тюрк с языком азербайджанским | 621 840 | 0,43 |

| 14 | Марийцы | мар, мари, марий, черемисы; горные марийцы, лугово-восточные марийцы | 604 298 | 0,42 |

| 15 | Немцы | голендры, дейч, дойч, меннонитен, меннониты, немцы-меннониты | 597 212 | 0,41 |

| 16 | Кабардинцы | адыгэ с языком кабардинским, кабардей | 519 958 | 0,36 |

| 17 | Осетины | дигорон (дигорцы), ирон (иронцы), туалаг, туальцы, | 514 875 | 0,35 |

| 18 | Даргинцы | дарган, дарганти, урбуган; кайтагцы, кубачинцы | 510 156 | 0,35 |

| 19 | Буряты | агинцы, баряад, буриад, буряад, казаки с языком бурятским, сартулы, хамниганы, хонгодоры, хоринцы, цонголы, а также булагаты, гураны, эхириты | 445 175 | 0,31 |

| 20 | Якуты | саха | 443 852 | 0,30 |

| 21 | Кумыки | кумук | 422 409 | 0,29 |

| 22 | Ингуши | галга | 413 016 | 0,28 |

| 23 | Лезгины | ахтинцы, кюрегу, кюринцы, лезги, лезгияр | 411 535 | 0,28 |

| 24 | Коми | зыряне, коми войтыр, коми-зыряне, коми йоз, коми морт; коми-ижемцы | 293 406 | 0,20 |

| 25 | Тувинцы | тува, тыва, тыва-кижи; тоджинцы | 243 442 | 0,17 |

| 26 | Евреи | ашкеназ, идн | 229 938 | 0,16 |

| 27 | Грузины | картвели; аджарцы, ингилойцы, лазы, мегрелы, сваны | 197 934 | 0,14 |

| 28 | Карачаевцы | карачай, карачайлыла, карачайлы | 192 182 | 0,13 |

| 29 | Цыгане | дом, ром, рома, сэрвы | 182 766 | 0,13 |

| 30 | Калмыки | большие дэрбэты, дербеты, дэрбеты, дюрбеты, казаки с языком калмыцким, ойраты, торгоуты, торгуты, хальмг, хойты, элеты | 173 996 | 0,12 |

| 31 | Молдаване | волохь, молдовень | 172 330 | 0,12 |

| 32 | Лакцы | вулугуни, лак, лаки, лаккучу, тумал, яхолшу | 156 545 | 0,11 |

| 33 | Корейцы | корё сарам, хангук сарам, чосон сарам | 148 556 | 0,10 |

| 34 | Казаки[108] | 140 028 | 0,10 | |

| 35 | Табасараны | кабган, кабгин, табасаран, табасаранцы | 131 785 | 0,09 |

| 36 | Адыгейцы | абадзехи, адыгэ с языком адыгейским, бесленеевцы с языком адыгейским, бжедуги, мамхеги, махмеги, махмеговцы | 128 528 | 0,09 |

| 37 | Коми-пермяки | коми с языком коми-пермяцким, коми морт с языком коми-пермяцким, коми отир, пермяки | 125 235 | 0,09 |

| 38 | Узбеки | озбак, тюрк с языком узбекским | 122 916 | 0,08 |

| 39 | Таджики | тоджик | 120 136 | 0,08 |

| 40 | Балкарцы | малкарцы, малкъарлыла, малкъарлы, таулу | 108 426 | 0,07 |

| 41 | Греки | греки-ромеи, греки-эллины, грекос, понтиос, ромеи, ромеос, ромеюс, рум, румей, эллинос | 97 827 | 0,07 |

| 42 | Карелы | карьяла, карьялайзет, карьялани, лаппи, ливвикёй, ливвики, ливгиляйне, людики, лююдикёй, лююдилайне с языком карельским | 93 344 | 0,06 |

| 43 | Турки | османы, турки-батумцы, турки-османы, турки-сухумцы, тюрк с языком турецким | 92 415 | 0,06 |

| 44 | Ногайцы | караногайцы, карагаши, ногай-карагаш, ногай | 90 666 | 0,06 |

| 45 | Мордва-эрзя[109] | терюхане, эрзя | 84 407 | 0,06 |

| 46 | Хакасы | качинцы, койбалы, кызыл, кызыльцы, сагай, сагайцы, тадар, тадар-кижи с языком хакасским, хаас, хааш, хойбал, хызыл | 75 622 | 0,05 |

| 47 | Поляки | поляци | 73 001 | 0,05 |

| 48 | Алтайцы | алтай-кижи, кыпчак с языком алтайским, майминцы, найман с языком алтайским | 67 239 | 0,05 |

| 49 | Черкесы | адыгэ с языком черкесским, бесленеевцы с языком кабардино-черкесским, бесленеи | 60 517 | 0,04 |

| 50 | Лугово-восточные марийцы[110] | ветлужские марийцы, восточные (уральские) марийцы, вутла мари, кожла марий, лесные марийцы, луговые марийцы, олык марий | 56 119 | 0,04 |

| 51 | Мордва-мокша[111] | мокша | 49 624 | 0,03 |

| 52 | Литовцы | жемайты, летувник, летувяй, литвины с языком литовским, литвяки с языком литовским | 45 569 | 0,03 |

| 53 | Ненцы | не, ненач, ненэй ненэц, ненэйне, нещанг, пян хасова, хандеяры | 41 302 | 0,03 |

| 54 | Абазины | абаза, ашхаруа, ашхарцы, тапанта | 37 942 | 0,03 |

| 55 | Эвенки | илэ, манегры, мурчен, орочён с языком эвенкийским, тонгус, тунгусы с языком эвенкийским | 35 527 | 0,02 |

| 56 | Китайцы | хань, ханьжэнь, чжунго жэнь | 34 577 | 0,02 |

| 57 | Финны | суомалайсет, суоми; финны-ингерманландцы | 34 050 | 0,02 |

| 58 | Туркмены | трухмены, тюрк с языком туркменским | 33 053 | 0,02 |

| 59 | Болгары | българи | 31 965 | 0,02 |

| 60 | Киргизы | кыргыз | 31 808 | 0,02 |

| 61 | Езиды | езды, иезиды, йезиды, эзды | 31 273 | 0,02 |

| 62 | Рутульцы | мегьебор, мых абдыр, мюхадар, рутул, хинатбы, хновцы | 29 929 | 0,02 |

| 63 | Ханты | кантага ях, остяки с языком хантыйским, хандэ, ханти, хантых, хантэ | 28 678 | 0,02 |

| 64 | Латыши | латвиетис, латвиеши | 28 520 | 0,02 |

| 65 | Агулы | агул шуй, агулар, агульцы | 28 297 | 0,02 |

| 66 | Эстонцы | чухонцы, эсты | 28 113 | 0,02 |

| 67 | Вьетнамцы | нгой вьет (всё коренное население Вьетнама) | 26 206 | 0,02 |

| 68 | Кряшены[112] | крещеные, крещенцы, крещеные татары | 24 668 | 0,02 |

| 69 | Андийцы[113] | андии, андал, гванал, кваннал, куаннал | 21 808 | 0,02 |

| 70 | Курды | курмандж | 19 607 | 0,01 |

| 71 | Эвены | илкан, ламут, ламут-наматкан, мэнэ, овен, овон, ороч с языком эвенским, орочёл, орочель, орочён с языком эвенским, тунгусы с языком эвенским, тургэхал, ывын, эбэн, эвон, эвын, эвэн, эвэс | 19 071 | 0,01 |

| 72 | Горные марийцы[114] | курык марий | 18 515 | 0,01 |

| 73 | Чукчи | анкалын, анкальын, луораветлан, лыгъоравэтлят, чаучу | 15 767 | 0,01 |

| 74 | Коми-ижемцы[115] | ижемцы, изьватас | 15 607 | 0,01 |

| 75 | Дидойцы[116] | цезы, цунтинцы | 15 256 | 0,01 |

| 76 | Шорцы | тадар-кижи с языком шорским, шор-кижи | 13 975 | 0,01 |

| 77 | Ассирийцы | айсоры, арамеи, асори, ассурайя, атурая, сурайя, халдеи | 13 649 | 0,01 |

| 78 | Гагаузы | гагауз | 12 210 | 0,01 |

| 79 | Нанайцы | гольды, нанай, нани с языком нанайским | 12 160 | 0,01 |

| 80 | Манси | вогулы, меньдси, моансь, остяки с языком мансийским | 11 432 | 0,01 |

| 81 | Абхазы | абжуйцы, апсуа, бзыбцы | 11 366 | 0,01 |

| 82 | Арабы | аль-араб, алжирцы, арабы ОАЭ, бахрейнцы, египтяне, иорданцы, иракцы, йеменцы, катарцы, кувейтцы, ливанцы, ливийцы, мавританцы, марокканцы, оманцы, палестинцы, саудовцы, сирийцы, суданцы, тунисцы | 10 630 | 0,01 |

| 83 | Цахуры | йыхбы | 10 366 | 0,01 |

| 84 | Пуштуны (афганцы) | афганцы, патаны, пахтуны | 9 800 | 0,00 |

| 85 | Сибирские татары[117] | бараба, барабинцы, бохарлы, бухарцы, заболотные татары, калмаки, курдакско-саргатские татары, параба, сибир татарлар, тарлик, тарские татары, тевризские татары, тоболик, тобольские татары, тураминцы, тюменско-тюринские татары, чаты, эуштинцы, ясколбинские татары | 9 611 | 0,00 |

| 86 | Нагайбаки | нагайбак | 9 600 | 0,00 |

| 87 | Коряки | алюторцы, алутальу, апокваямыл`о, апукинцы, войкыпал`о, воямпольцы, каменцы, карагинцы, каран`ыныльо, нымыланы, олюторцы, чавчувены, чавчыв | 8 743 | 0,00 |

| 88 | Вепсы | бепся, вепся, людиникат, лююдилайне с вепсским языком, чудь, чухари | 8 240 | 0,00 |

| 89 | Долганы | долган, дулган, саха с долганским языком | 7 261 | 0,00 |

| 90 | Поморы[118] | канинские поморы | 6 571 | 0,00 |

| 91 | Ахвахцы[119] | ахвалал, ашватл, ашвалъ | 6 376 | 0,00 |

| 92 | Бежтинцы[120] | капучины, хванал | 6 198 | 0,00 |

| 93 | Каратинцы[121] | кирди | 6 052 | 0,00 |

| 94 | Румыны | ромынь | 5 308 | 0,00 |

| 95 | Нивхи | гиляки, нибах, нивах, нивух, нивхгу, ньигвнгун | 5 162 | 0,00 |

| 96 | Индийцы (хинди) | индийцы хиндиязычные, хинди, хиндустанцы | 4 980 | 0,00 |

| 97 | Тоджинцы (тыва-тоджинцы)[122] | тоджинцы, тувинцы-тоджинцы, туга, туха | 4 442 | 0,00 |

| 98 | Селькупы | остяки с языком селькупским, сёлькуп, суссе кум, чумыль-куп, шелькуп, шешкум | 4 249 | 0,00 |

| 99 | Сербы | срби | 4 156 | 0,00 |

| 100 | Крымские татары | кърым татарлар, ногаи крымские, нугай татар, татары крымские, тат с языком крымскотатарским | 4 131 | 0,00 |

| 101 | Персы | иранцы, мавры, парс, фарс | 3 821 | 0,00 |

| 102 | Венгры | мадьяр | 3 768 | 0,00 |

| 103 | Удины | уди, ути | 3 721 | 0,00 |

| 104 | Горские евреи (таты-иудаисты) | дагестанские евреи, даг-чуфут, джуфут, джухут, татские евреи, таты-иудаисты | 3 394 | 0,00 |

| 105 | Турки-месхетинцы | (турки, депортированные из Месхетии (Самцхе Грузии) в сер. XX в. в Среднюю Азию) | 3 257 | 0,00 |

| 106 | Шапсуги | адыге-шапсуги | 3 231 | 0,00 |

| 107 | Ительмены | ительмень, камчадалы с языком ительменским | 3 180 | 0,00 |

| 108 | Бесермяне | бешермяне | 3 122 | 0,00 |

| 109 | Кумандинцы | кубанды, куманды, орё куманды, тадар-кижи с языком кумандинским, тюбере куманды | 3 114 | 0,00 |

| 110 | Ульчи | мангуны, нани, ульча с языком ульчским | 2 913 | 0,00 |

| 111 | Чехи | чеши, мораване | 2 904 | 0,00 |

| 112 | Уйгуры | илийцы, кашгарцы, таранчи | 2 867 | 0,00 |

| 113 | Сойоты | саяты | 2 769 | 0,00 |

| 114 | Монголы | халха, халха-монголы, халхасцы | 2 656 | 0,00 |

| 115 | Телеуты | тадар-кижи с языком телеутским | 2 650 | 0,00 |

| 116 | Талыши | талышон | 2 548 | 0,00 |

| 117 | Теленгиты | телесы | 2 399 | 0,00 |

| 118 | Таты | тат, таты-азербайджанцы | 2 303 | 0,00 |

| 119 | Камчадалы | 2 293 | 0,00 | |

| 120 | Астраханские татары[123] | алабугатские татары, юртовские татары | 2 003 | 0,00 |

| 121 | Саамы | лопари, саами | 1 991 | 0,00 |

| 122 | Эскимосы | сиренигмит, уназигмит, юпагыт, юпит | 1 750 | 0,00 |

| 123 | Удэгейцы | удэ, удэхе, удэхейцы | 1 657 | 0,00 |

| 124 | Латгальцы[124] | латгалиетис | 1 622 | 0,00 |

| 125 | Каракалпаки | калпак, каролпак | 1 609 | 0,00 |

| 126 | Тубалары | туба | 1 565 | 0,00 |

| 127 | Испанцы | эспаньолес | 1 547 | 0,00 |

| 128 | Хемшилы | армяне-мусульмане, хамшены, хамшецы, хемшины | 1 542 | 0,00 |

| 129 | Юкагиры | алаи, ваду, деткиль, дудки, одул, омоки, хангайцы | 1 509 | 0,00 |

| 130 | Кеты | денг, кето, остяки с языком кетским | 1 494 | 0,00 |

| 131 | Американцы США | американцы, «Ю.Эс. Амэрикенс» | 1 275 | 0,00 |

| 132 | Чуванцы | атали, марковцы, этели | 1 087 | 0,00 |

| 133 | Гунзибцы[125] | гунзал, нахада, хунзалис, хунзалы | 998 | 0,00 |

| 134 | Итальянцы | итальяни | 862 | 0,00 |

| 135 | Челканцы | чалканцы | 855 | 0,00 |

| 136 | Тофалары | тофы | 837 | 0,00 |

| 137 | Японцы | нихондзин | 835 | 0,00 |

| 138 | Нганасаны | ня, тавгийцы | 834 | 0,00 |

| 139 | Французы | франсэ | 819 | 0,00 |

| 140 | Дунгане | лао хуйхуй, хуйцзу, хуэй | 801 | 0,00 |

| 141 | Кубинцы | кубаньос | 707 | 0,00 |

| 142 | Орочи | нани с языком орочским, ороч с языком орочским, орочён с языком орочским, орочисэл | 686 | 0,00 |

| 143 | Чулымцы | карагасы томские, чулымские татары, чулымские тюрки | 656 | 0,00 |

| 144 | Осетины-дигорцы[126] | дигор, дигорон, дигорцы | 607 | 0,00 |

| 145 | Словаки | словаци | 568 | 0,00 |

| 146 | Негидальцы | амгун бэйенин, на бэйенин, негды, нясихагил, элькан дэйнин | 567 | 0,00 |

| 147 | Алеуты | ангагинас, сасигнан, унан`ах, унанган | 540 | 0,00 |

| 148 | Гинухцы[127] | 531 | 0,00 | |

| 149 | Англичане | инглиш | 529 | 0,00 |

| 150 | Бенгальцы | бенгали | 489 | 0,00 |

| 151 | Среднеазиатские цыгане | гурбат, джуги, люли, мугат, мультони, тавоктарош | 486 | 0,00 |

| 152 | Мегрелы[128] | маргали, мингрелы | 433 | 0,00 |

| 153 | Хорваты | хрвати | 412 | 0,00 |

| 154 | Караимы | карай | 366 | 0,00 |

| 155 | Ульта (ороки) | ороки, ороч с языком ульта, орочён с языком ульта, уйльта, ульта, ульча с языком ульта | 346 | 0,00 |

| 156 | Нидерландцы (голландцы) | недерландерс | 334 | 0,00 |

| 157 | Ижорцы | ижора, изури, ингры, карьяляйн | 327 | 0,00 |

| 158 | Финны-ингерманландцы[129] | ингерманландцы, инкерилайнен | 314 | 0,00 |

| 159 | Шведы | свенскар | 295 | 0,00 |

| 160 | Тазы (удэ) | удэ с языком китайским или русским | 276 | 0,00 |

| 161 | Албанцы | шкиптарёт, шкипетары; арнауты | 272 | 0,00 |

| 162 | Австрийцы | остарайха, остеррайхер | 261 | 0,00 |

| 163 | Аджарцы[130] | аджарели | 252 | 0,00 |

| 164 | Энцы | могади, пэ-бай, эньчо | 237 | 0,00 |

| 165 | Лазы[131] | 221 | 0,00 | |

| 166 | Чеченцы-аккинцы[132] | аккинцы, ауховцы | 218 | 0,00 |

| 167 | Сету[133] | полуверцы, сето, сету, эстонцы-сету | 197 | 0,00 |

| 168 | Среднеазиатские арабы | араби | 181 | 0,00 |

| 169 | Крымчаки | крымские евреи | 157 | 0,00 |

| 170 | Черногорцы | црногорци | 131 | 0,00 |

| 171 | Хваршины[134] | инхокваринцы, хваршал, хваршинцы, хуани | 128 | 0,00 |

| 172 | Русины | бойки, карпатороссы, лемки | 97 | 0,00 |

| 173 | Осетины-иронцы[135] | ирон, иронцы, кудайраг, кударцы | 97 | 0,00 |

| 174 | Арчинцы[136] | арчи, арчиб | 89 | 0,00 |

| 175 | Кубачинцы[137] | угбуган | 88 | 0,00 |

| 176 | Португальцы | португьесес | 87 | 0,00 |

| 177 | Белуджи | балочи, белучи | 81 | 0,00 |

| 178 | Водь | вадьяко | 73 | 0,00 |

| 179 | Ингилойцы[138] | ингилой | 63 | 0,00 |

| 180 | Среднеазиатские евреи | бани исроил, бухарские евреи, дживут бухари, джугут, иври, исроэл, яхуди, яхудои махали | 54 | 0,00 |

| 181 | Греки-урумы[139] | орум, урмей, урум | 54 | 0,00 |

| 182 | Грузинские евреи | эбраэли | 53 | 0,00 |

| 183 | Тиндалы[140] | идари, идери, тиндии, тиндинцы | 44 | 0,00 |

| 184 | Сваны[141] | свани | 41 | 0,00 |

| 185 | Багулалы[142] | багвалалы, багвалинцы, багулав, гантляло, кванадлетцы, тлибишинцы, тлиссинцы | 40 | 0,00 |

| 186 | Годоберинцы[143] | гибдиди, ибдиди | 39 | 0,00 |

| 187 | Рушанцы | рушони, рухни | 27 | 0,00 |

| 188 | Баджуйцы | баджавидж, баджуведж, баджувцы | 21 | 0,00 |

| 189 | Юги[144] | юген | 19 | 0,00 |

| 190 | Ботлихцы[145] | 16 | 0,00 | |

| 191 | Шугнанцы | шугни, хугни. хунуни | 14 | 0,00 |

| 192 | Чамалалы[146] | чамалалы, чамалинцы | 12 | 0,00 |

| 193 | Кереки | 8 | 0,00 | |

| 194 | Кайтагцы[147] | 5 | 0,00 | |

| 195 | Арнауты[148] | 5 | 0,00 | |

| … | прочие | 40 551 | 0,03 | |

| … | не указавшие национальность | 1 460 751 | 1,01 | |

| … | ВСЕГО, РФ[149] | 145 166 731 | 100,00 |

Национальный состав населения Крыма[편집]

Рождаемость[편집]

Репродуктивные установки и нормы детности в России имеют этнические особенности[150]. Проведенные исследования показали, что рождаемость одного и того же этноса в разных регионах ближе, чем рождаемость разных этносов в одном регионе[151]. По переписи 2002 года самый высокий уровень рождаемости в России был у дидойцев (3,038 рождённых ребёнка в среднем на женщину), курдов (2,581), турок (2,512), цыган (2,451) и ненцев (2,421), а самый низкий уровень рождаемости в России у евреев (1,264), русских (1,446), грузин (1,480)[152]. Однако микроперепись 2015 года зафиксировала продолжение процесса уменьшения этнической дифференциации уровня рождаемости в России[153].

| Народы | 1897 | 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Все население | 1417 | 1269 | 1070 | 876 | 731 | 656 | 747 | 396 | 455 |

| Русские | 1310 | 1233 | 1191 | 863 | 703 | 667 | 759 | 384 | 450 |

| Татары | 1454 | 1432 | 1592 | 1105 | 992 | 680 | 713 | 374 | 401 |

| Чеченцы | 1904 | 1805 | 2174 | 2179 | 2256 | 1400 | 1267 | 942 | 1027 |

| Евреи | 1490 | 795 | 824 | 337 | 296 | 305 | 343 | 225 | 286 |

Самые высокие показатели рождаемости у ингушей (2257 детей на 1 000 женщин), чеченцев (2196) и даргинцев (1975). А также у якутов и бурятов. Ниже всего у русских: на 1000 женщин 1405 детей[155]. Одна женщина в возрасте 50 — 54 лет за свою жизнь родила детей: ингушка 3,55, цыганка 3,46, чеченка 3,15, даргинка 3,06, тувинка 3,06, аварка 2,93, кумычка 2,74, лезгинка 2,73, таджичка 2,73, азербайджанка 2,5, бурятка 2,5, якутка 2,5, узбечка 2,48, кабардинка 2,4, карачаевка 2,39, казашка 2,36, балкарка 2,27, марийка 2,26, немка 2,25, башкирка 2,2, калмычка 2,18, армянка 2,17, удмуртка 2,16, чувашка 2,14, коми 2,1, осетинка 2,09, адыгейка 2, татарка 1,93, мордовка 1,91, украинка 1,89, белоруска 1,85, русская 1,78 и еврейка 1,45[156].

Возрастная структура[편집]

| Доля пожилых (60 лет и старше) % |

Уровень старости [~ 1] |

Доля в населении России (% к указавшим национальность) 2002 |

Доля в населении России (% к указавшим национальность) 2010 |

Народы |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Демографическая молодость | ||||

| ~6 | до 0,25 | 2,17 | 2,78 | киргизы, таджики, турки, цыгане, тофалары[~ 2], чукчи, нганасаны[~ 2], ненцы, уйльта[~ 2], чеченцы, юкагиры[~ 2], ханты, тувинцы, орочи[~ 2], коряки, эскимосы[~ 2], манси, азербайджанцы, нивхи[~ 2], долганы, кеты[~ 2], узбеки, ингуши, сойоты[~ 2], эвенки, энцы* |

| Преддверие старости | ||||

| ~8 | 0,25—0,4 | 2,56 | 2,6 | табасараны, негидальцы, эвены[~ 2], селькупы[~ 2], цахуры[~ 2], кумыки, нанайцы[~ 2], ульчи[~ 2], рутульцы[~ 2], даргинцы, аварцы, лезгины, алтайцы, чуванцы[~ 2], удэгейцы[~ 2], агулы[~ 2], якуты, лакцы, ногайцы |

| Старость — невысокий уровень | ||||

| ~12 | 0,4—0,9 | 4,39 | 3,82 | ительмены[~ 2], чулымцы[~ 2], саами[~ 2], алеуты[~ 2], буряты, калмыки, казахи, хакасы, карачаевцы, шорцы[~ 2], кабардинцы, балкарцы, телеуты[~ 2], черкесы, камчадалы[~ 2], абазины[~ 2], армяне, башкиры, адыгейцы |

| Старость — заметный уровень | ||||

| ~18 | 0,9—1,5 | 6,35 | 6,11 | (без русских) тазы, осетины, шапсуги, корейцы, марийцы, кумандинцы, молдаване, грузины, татары, греки, чуваши |

| 80,64 | 80,9 | русские | ||

| Старость — значительный уровень | ||||

| ~20 | 1,5—4 | 0,74 | 1,47 | удмурты, коми, коми-пермяки, нагайбаки, бесермяне, немцы, мордва |

| Старость — высокий уровень | ||||

| ~30 | 4—7,5 | 2,62 | 0,06 | карелы, финны, вепсы |

| Старость — крайне высокий уровень | ||||

| ~40 | 7,5+ | 0,16 | 1,9 | евреи, украинцы, белорусы |

См. также[편집]

- Национальный состав населения России в 2010 году

- Расселение народов России

- Этноязыковой состав населения России (1989, 2002, 2010 гг.)

- Народности России (серия статуэток)

Примечания[편집]

- Сноски

- Источники

Ссылки[편집]

- Сайт Всероссийской переписи населения 2002

- Сайт Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 Archived 2014년 2월 21일 - 웨이백 머신

- Убыль или прирост русских в регионах России. Процент новорожденных этнических русских относительно процента этнических русских всех возрастов.

- Всероссийская перепись 2010 года. Женщины наиболее многочисленных национальностей РФ, проживающие в частных домохозяйствах, по возрастным группам и числу рождённых детей Демоскоп

Литература[편집]

- Водарский Я. Е., Кабузан В. М. Территория и население России в XV—XVIII веках // Российская империя. От истоков до начала XIX века. Очерки социально-политической и экономической истории / редакторы А. И. Аксёнов, Я. Е. Водарский, Н. И. Никитин, Н. М. Рогожин — М.: Русская панорама, 2011. — 880 с. — ISBN 978-5-93165-267-2.

- Кабузан В. М. Народы России в XVIII в.: Численность и этнический состав — М.: Наука, 1990. — ISBN 5-02-009518-4.

- Население России за 100 лет (1897—1997): Стат. сб — М.: Госкомстат России, 1998. — 222 с. — ISBN 5-89476-014-3.

| 러시아의 정치 |

|

|

펼침/접힘 설정: 현재 기본값 autocollapse

이 틀이 처음 나타날 때의 가시성을 설정하려면 |state= 매개변수를 쓰세요.

|state=collapsed: 접어서 나타내려면{{Evraziskykr|state=collapsed}}|state=expanded: 펼쳐서 나타내려면{{Evraziskykr|state=expanded}}|state=autocollapse:{{Evraziskykr|state=autocollapse}}

|state= 매개변수가 설정되지 않은 경우, 초기 가시성은 이 틀의 |default= 매개변수에서 가져옵니다. 이 페이지의 틀은 현재 autocollapse입니다.

빅토르 볼로디미로비치 메드베드추크 (우크라이나어:Ві́ктор Володи́мирович Медведчу́к, 1954년 8월 7일, 소련 러시아 소비에트 사회주의 연방 공화국, 크라스노야르스크 크라이, 1954년 8월 7일 ~)는 우크라이나의 정치인, 변호사, 올리가르히이다.[158][159] 2019년부터 우크라이나 국회의원으로 재직하고 있다.

메드베드추크는 2002년부터 2005년까지 전 우크라이나 대통령 레오니드 쿠치마의 비서실장을 지낸 인물이다.

현재 메드베드추크는 친러시아 정치 조직 우크라이나의 선택의 의장이며, 우크라이나의 유럽 연합 가입을 반대하고 있다.[160]

2018년 11월, 메드베드추크는 인생을 위한 당의 정치위원회 의장으로 선출되었고, 이 정당은 훗날 인생을 위한 야권연단으로 합병되었다.[161]

어린 시절과 교육[편집]

각주[편집]

- ↑ Екатерина Щербакова. Доля титульной национальности возрастает во всех странах СНГ, кроме России // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — № 559—560.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Официальный сайт Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года. Информационные материалы об окончательных итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Всероссийская перепись населения 2010. Национальный состав населения РФ 2010

- ↑ 가 나 Официальный сайт Всероссийской переписи населения 2002 года — Национальный состав населения

- ↑ 가 나 Официальный сайт Всероссийской переписи населения 2002 года — Перечень вариантов самоопределения национальности с численностью

- ↑ 가 나 Всероссийская перепись населения 2002. Национальный состав населения с самоназваниями и в том числе.

- ↑ Численность, удельный вес и половой состав украинского населения России, 1926—2010 гг. / Завьялов А. В. Социальная адаптация украинских иммигрантов : монография. — Иркутск: Изд-во ИГУ, 2017. — 179 с. — ISBN 978-5-9624-1479-9

- ↑ 가 나 다 К андо-цезским народностям относят следующие этносы: андийцы (21808 чел., 2002 г.; 11789 чел., 2010 г.), дидойцы (цезы) (15256 чел., 2002 г.; 11683 чел., 2010 г.), ахвахцы, багулалы, бежтинцы, ботлихцы, гинухцы, годоберинцы, гунзибцы, каратинцы, тиндинцы, хваршины, чамалинцы.

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. выделялись отдельно, по переписи 2010 г. в составе алтайцев учитывались теленгиты, тубалары, челканцы. В таблице численность представлена включая их в составе алтайцев и по 2010 г., и по 2002 г.

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. казаки включены в состав русских

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. мордва-эрзя (эрзяне) включены в состав мордвы

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. кряшены (крещённые татары или татары-христиане) включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. горные марийцы включены в состав марийцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. андийцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. дидойцы (цезы) включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. ахвахцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. сибирские татары включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. коми-ижемцы включены в состав коми

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. бежтинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. каратинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. мордва-мокша (мокшане) включены в состав мордвы

- ↑ 가 나 По переписи 2002 г. теленгиты выделялись отдельно, по переписи 2010 г. — включены в состав алтайцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. ботлихцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. поморы включены в состав русских

- ↑ 가 나 По переписи 2002 г. тубалары выделялись отдельно, по переписи 2010 г. — включены в состав алтайцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. тувинцы-тоджинцы включены в состав тывы (тувинцев)

- ↑ 가 나 По переписи 2002 г. челканцы выделялись отдельно, по переписи 2010 г. — включены в состав алтайцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. латгальцы включены в состав латышей

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. гунзибцы были включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. мишари не выделялись (мишари (486 чел.), мишэр (32 чел.), мещеряки (39 чел.) по переписным листам, 2002) и включались в состав татар, по переписи 2010 г. — выделены в составе татар отдельной этногруппой

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. тиндалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. мегрелы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. хваршины включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи отдельно выделялись белуджи (81 чел., 2002). В переписи 2010 г. выделено обобщённое «пакистанцы», к которым относятся пенджабцы, белуджи, синдхи и др.

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. гинухцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. финны-ингерманландцы включены в состав финнов

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. годоберинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. осетины-дигорцы (дигорцы) включены в состав собственно осетин

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. лугово-восточные марийцы включены в состав марийцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. сету включены в состав эстонцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. аджарцы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. лазы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. кубачинцы включены в состав даргинцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. ингилойцы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. чеченцы-аккинцы включены в состав чеченцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. осетины-иронцы (иронцы) включены в состав собственно осетин

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. сваны включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. курманч отдельно не выделялись (1 чел. в переписных листах отнесён к курдам, 2002), по переписи 2010 г. — выделены отдельной этногруппой в составе курдов

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. чамалалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. карагаши включены в состав ногайцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. арчинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. кайтагцы включены в состав даргинцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. астраханские татары включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. черкесогаи выделены этногруппой в составе армян

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. багулалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. меннониты включены в состав немцев

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. греки-урумы включены в состав греков

- ↑ По переписям 2002 и 2010 г. юги включены в состав кетов

- ↑ По переписям 2002 выделялись, а по переписи 2010 не выделялись: нидерландцы (голландцы) (334 чел.), шведы (295 чел.), албанцы (272 чел.) австрийцы (261 чел.), среднеазиатские арабы (181 чел.), португальцы (87 чел.) — всего 1430 чел., вошедших в «прочие»

- ↑ 가 나 Постоянное население РФ по состоянию на момент переписи — 14.10.2010 г.

- ↑ Валерий Тишков, Валерий Степанов. Российская перепись в этническом измерении. Кто численно возрастает, а кто — депопулирует? // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — 19 апреля — 2 мая 2004. — № 155—156.

- ↑ Численность, удельный вес и половой состав украинского населения России, 1926—2010 гг. / Завьялов А. В. Социальная адаптация украинских иммигрантов : монография. — Иркутск: Изд-во ИГУ, 2017. — 179 с.

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. казаки включены в состав русских

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. мордва-эрзя (эрзяне) включены в состав мордвы

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. кряшены (крещённые татары или татары-христиане)) включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. горные марийцы включены в состав марийцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. андийцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. дидойцы (цезы) включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. ахвахцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. сибирские татары включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. коми-ижемцы включены в состав коми

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. бежтинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. каратинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. мордва-мокша (мокшане) включены в состав мордвы

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. ботлихцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. поморы включены в состав русских

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. тувинцы-тоджинцы включены в состав тывы (тувинцев)

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. латгальцы включены в состав латышей

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. гунзибцы были включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. мишари не выделялись, по переписи 2010 г. — включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. тиндалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. мегрелы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. хваршины включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. гинухцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. финны-ингерманландцы включены в состав финнов

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. годоберинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. осетины-дигорцы (дигорцы) включены в состав собственно осетин

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. лугово-восточные марийцы включены в состав марийцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. сету включены в состав эстонцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. аджарцы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. лазы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. кубачинцы включены в состав даргинцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. ингилойцы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. чеченцы-аккинцы включены в состав чеченцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. осетины-иронцы (иронцы) включены в состав собственно осетин

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. сваны включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. курманч не выделялись, по переписи 2010 г. — включены в состав курдов

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. чамалалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. карагаши не выделялись, по переписи 2010 г. — включены в состав ногайцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. арчинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. кайтагцы включены в состав даргинцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. астраханские татары включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. черкесогаи включены в состав армян

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. багулалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. меннониты включены в состав немцев

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. греки-урумы включены в состав греков

- ↑ По переписи 2010 г. юги включены в состав кетов

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. казаки включены в состав русских

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. мордва-эрзя (эрзяне) включены в состав мордвы

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. лугово-восточные марийцы включены в состав марийцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. мордва-мокша (мокшане) включены в состав мордвы

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. кряшены (крещённые татары или татары-христиане)) включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. андийцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. горные марийцы включены в состав марийцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. коми-ижемцы включены в состав коми

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. дидойцы (цезы) включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. сибирские татары включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. поморы включены в состав русских

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. ахвахцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. бежтинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. каратинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. тоджинцы включены в состав тывы (тувинцев)

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. астраханские татары включены в состав татар

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. латгальцы включены в состав латышей

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. гунзибцы были включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. осетины-дигорцы (дигорцы) включены в состав собственно осетин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. гинухцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. мегрелы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. финны-ингерманландцы включены в состав финнов

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. аджарцы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. лазы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. чеченцы-аккинцы включены в состав чеченцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. сету включены в состав эстонцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. хваршины включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. осетины-иронцы (иронцы) включены в состав собственно осетин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. арчинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. кубачинцы включены в состав даргинцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. ингилойцы включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. греки-урумы включены в состав собственно греков

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. тиндалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. сваны включены в состав грузин

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. багулалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. годоберинцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. юги включены в состав кетов

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. ботлихцы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. чамалалы включены в состав аварцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. кайтагцы включены в состав даргинцев

- ↑ По переписи 2002 г. арнауты включены в состав албанцев

- ↑ Постоянное население РФ по состоянию на момент переписи — 9.10.2002 г.

- ↑ Лилия Карачурина. Региональные особенности российской демографической ситуации // «Отечественные записки», 2006, № 4.

- ↑ Гульназ Галеева. Сравнительная характеристика рождаемости наиболее многочисленных этносов Республики Башкортостан, проживающих внутри и за пределами региона // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — 10 — 23 февраля 2014. — № 585—586.

- ↑ Архангельский В. Н. Этническая дифференциация рождаемости и репродуктивного поведения в России // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — 27 ноября — 10 декабря 2006. — № 267—268.

- ↑ Евгений Андреев, Сергей Захаров. Микроперепись-2015 ставит под сомнение результативность мер по стимулированию рождаемости. Межэтнические различия рождаемости в России: долговременные тенденции // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — 1 — 22 января 2017. — № 711—712.

- ↑ Дмитрий Богоявленский. Перепись 2010: этнический срез. Рождаемость народов через призму детности // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — 12 — 25 ноября 2012. — № 531—532.

- ↑ Росстат отчитался: Рекордсмены по рождаемости — горячий Кавказ и холодная Якутия

- ↑ Россия кавказцами и азиатами прирастать будет // Комсомольская правда, 29.11.2012.

- ↑ Дмитрий Богоявленский. Перепись 2010: этнический срез. «Седеющие» народы // Демоскоп Weekly : сайт. — № 531—532.

- ↑ Virtual Politics - Faking Democracy in the Post-Soviet World, Andrew Wilson, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-09545-7

- ↑ Kinstler, Linda (2015년 5월 28일). “The 12 people who ruined Ukraine”. 《POLITICO》.

- ↑ Kremlin-imposed "Ukrainian choice", The Ukrainian Week (3 July 2012).

Playing opposition, Den (15 August 2013).

Russia's Plan For Ukraine: Purported Leaked Strategy Document Raises Alarm, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (20 August 2013). - ↑ “Medvedchuk elected head of political board of Za Zhyttia party”. 《Interfax-Ukraine》.

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. Its momentum and interest grew in the early 19th century, when increasingly serious and learned admirers of neo-Gothic styles sought to revive medieval Gothic architecture, in contrast to the neoclassical styles prevalent at the time. Gothic Revival draws features from the original Gothic style, including decorative patterns, finials, lancet windows, and hood moulds. By the mid-19th century, it was established as the preeminent architectural style in the Western world.

The Gothic Revival movement's roots are intertwined with deeply philosophical movements associated with Catholicism and a re-awakening of high church or Anglo-Catholic belief concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism. Ultimately, the "Anglo-Catholicism" tradition of religious belief and style became known for its intrinsic appeal in the third quarter of the 19th century. Gothic Revival architecture varied considerably in its faithfulness to both the ornamental style and principles of construction of its medieval original, sometimes amounting to little more than pointed window frames and a few touches of Gothic decoration on a building otherwise on a wholly 19th-century plan and using contemporary materials and construction methods.

In parallel to the ascendancy of neo-Gothic styles in 19th-century England, interest spread to the rest of Europe, Australia, Africa and the Americas; the 19th and early 20th centuries saw the construction of very large numbers of Gothic Revival structures worldwide. The influence of Revivalism had nevertheless peaked by the 1870s. New architectural movements, sometimes related as in the Arts and Crafts movement, and sometimes in outright opposition, such as Modernism, gained ground, and by the 1930s the architecture of the Victorian era was generally condemned or ignored. The later 20th century saw a revival of interest, manifested in the United Kingdom by the establishment of the Victorian Society in 1958.

Roots[편집]

The rise of evangelicalism in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw in England a reaction in the high church movement which sought to emphasise the continuity between the established church and the pre-Reformation Catholic church.[1] Architecture, in the form of the Gothic Revival, became one of the main weapons in the high church's armoury. The Gothic Revival was also paralleled and supported by "medievalism", which had its roots in antiquarian concerns with survivals and curiosities. As "industrialisation" progressed, a reaction against machine production and the appearance of factories also grew. Proponents of the picturesque such as Thomas Carlyle and Augustus Pugin took a critical view of industrial society and portrayed pre-industrial medieval society as a golden age. To Pugin, Gothic architecture was infused with the Christian values that had been supplanted by classicism and were being destroyed by industrialisation.[2]

Gothic Revival also took on political connotations; with the "rational" and "radical" Neoclassical style being seen as associated with republicanism and liberalism (as evidenced by its use in the United States and to a lesser extent in Republican France), the more spiritual and traditional Gothic Revival became associated with monarchism and conservatism, which was reflected by the choice of styles for the rebuilt government centres of the British parliament's Palace of Westminster in London, the Canadian Parliament Buildings in Ottawa and the Hungarian Parliament Building in Budapest.[3]

In English literature, the architectural Gothic Revival and classical Romanticism gave rise to the Gothic novel genre, beginning with The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole,[4] and inspired a 19th-century genre of medieval poetry that stems from the pseudo-bardic poetry of "Ossian". Poems such as "Idylls of the King" by Alfred, Lord Tennyson recast specifically modern themes in medieval settings of Arthurian romance. In German literature, the Gothic Revival also had a grounding in literary fashions.[5]

Survival and revival[편집]

Gothic architecture began at the Basilica of Saint Denis near Paris, and the Cathedral of Sens in 1140[6] and ended with a last flourish in the early 16th century with buildings like Henry VII's Chapel at Westminster.[7] However, Gothic architecture did not die out completely in the 16th century but instead lingered in on-going cathedral-building projects; at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and in the construction of churches in increasingly isolated rural districts of England, France, Germany, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and in Spain.[8] Londonderry Cathedral (completed 1633) was a major new structure in the Perpendicular Gothic style.[9]

In Bologna, in 1646, the Baroque architect Carlo Rainaldi constructed Gothic vaults (completed 1658) for the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, which had been under construction since 1390; there, the Gothic context of the structure overrode considerations of the current architectural mode. Guarino Guarini, a 17th-century Theatine monk active primarily in Turin, recognized the "Gothic order" as one of the primary systems of architecture and made use of it in his practice.[10]

Likewise, Gothic architecture survived in an urban setting during the later 17th century, as shown in Oxford and Cambridge, where some additions and repairs to Gothic buildings were considered to be more in keeping with the style of the original structures than contemporary Baroque. Sir Christopher Wren's Tom Tower for Christ Church, University of Oxford,[a] and, later, Nicholas Hawksmoor's west towers of Westminster Abbey, blur the boundaries between what is called Gothic survival and the Gothic Revival.[12] Throughout France in the 16th and 17th centuries, churches such as St-Eustache continued to be built following Gothic forms cloaked in classical details, until the arrival of Baroque architecture.[13]

During the mid-18th century rise of Romanticism, an increased interest and awareness of the Middle Ages among influential connoisseurs created a more appreciative approach to selected medieval arts, beginning with church architecture, the tomb monuments of royal and noble personages, stained glass, and late Gothic illuminated manuscripts. Other Gothic arts, such as tapestries and metalwork, continued to be disregarded as barbaric and crude, however sentimental and nationalist associations with historical figures were as strong in this early revival as purely aesthetic concerns.[15]

German Romanticists (including philosopher and writer Goethe and architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel), began to appreciate the picturesque character of ruins—"picturesque" becoming a new aesthetic quality—and those mellowing effects of time that the Japanese call wabi-sabi and that Horace Walpole independently admired, mildly tongue-in-cheek, as "the true rust of the Barons' wars".[b][16] The "Gothick" details of Walpole's Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill House begun in 1749, appealed to the rococo tastes of the time,[c][18] and were fairly quickly followed by James Talbot at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire.[19] By the 1770s, thoroughly neoclassical architects such as Robert Adam and James Wyatt were prepared to provide Gothic details in drawing-rooms, libraries and chapels and, for William Beckford at Fonthill in Wiltshire, a complete romantic vision of a Gothic abbey.[d][22]