사용자:Js091213/비소

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 개요 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 영어명 | Arsenic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 표준 원자량 (Ar, standard) | 74.921595(6) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 주기율표 정보 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 원자 번호 (Z) | 33 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 족 | 15족 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 주기 | 4주기 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 구역 | p-구역 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 화학 계열 | 준금속 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

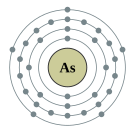

| 전자 배열 | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 준위별 전자 수 | 2, 8, 18, 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 물리적 성질 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 겉보기 | 회색의 금속, 광택 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 상태 (STP) | 고체 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 녹는점 | (28기압) 1090 K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 승화점 | 887 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 밀도 (상온 근처) | 5.727 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 융해열 | (gray) 24.44 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 기화열 | ??? 34.76 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 몰열용량 | 24.64 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 증기 압력 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 원자의 성질 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 산화 상태 | ±3, 5 (mildly acidic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 전기 음성도 (폴링 척도) | 2.18 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 이온화 에너지 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 원자 반지름 | 115 pm (실험값) 114 pm (계산값) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 공유 반지름 | 119 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 판데르발스 반지름 | 185 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 그 밖의 성질 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 결정 구조 | 마름모계 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 열전도율 | 50.2 W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 전기 저항도 | 333 n Ω·m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 자기 정렬 | 반자성[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 영률 | 8 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 부피 탄성 계수 | 22 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 모스 굳기계 | 3.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 브리넬 굳기 | 1440 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS 번호 | 7740-38-2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

이 문서는 다른 언어판 위키백과의 문서(en:Arsenic)를 번역 중이며, 한국어로 좀 더 다듬어져야 합니다. |

번역 과정: 31% 진행('화합물'까지 완료)

비소(←영어: arsenic 아르세닉/알세닉[*])는 화학 원소로 기호는 As, 원자 번호는 33이다. 비소는 많은 광물에 함유되어 있는데, 주로 황과 금속과 함께 함유되어 있지만, 순수한 결정형으로 존재하기도 한다. 비소는 준금속에 속한다. 이것은 다양한 동소체를 가지고 있지만, 공업적으로는 오직 회색의 형태만 중요하게 쓰인다.

금속 비소의 대표적 이용은 납과의 합금으로 쓰인다(예를 들자면, 자동차 축전지나 탄약이 있다). 비소는 N형 반도체 전자 기기의 도판트(불순물)로 쓰이고, 광전자 화합물인 비화 갈륨은 도판트(불순물)에 규소 다음으로 많이 쓰인다. 비소와 비소의 화합물 중 특별히 삼산화 화합물은 농약, 목재의 방부제, 제초제, 살충제에 쓰이지만, 점차 다른 물질로 대체되고 있는 추세다.[2]

일부 미생물들은 비소 화합물을 호흡 대사 산물로 쓸 수 있다. 사람을 포함해서, 쥐, 햄스터, 염소, 닭 등에 들어있는 극미량의 비소는 필수적인 무기질이다. 그러나, 필요 이상 섭취할 시 다세포가 비소 중독에 걸린다. 하천 비소 오염은 전 세계 몇백만 명의 사람에게 큰 영향을 끼치는 문제가 있다.

성질[편집]

물리적 성질[편집]

가장 흔한 비소 동소체는 3종류가 있다. 이들은 각각 금속 회색, 황색, 그리고 흑색 비소가 있는데, 이들 중 가장 흔한 것은 회색이다.[3] 회색 비소(α-As, 공간군 R3m No. 166)는 맞물리거나, 주름지거나, 육원자 고리 형태인 이중 층구조로 구성된 물질과 결합한다. 그로 인해 층마다 약한 결합을 유지하게 되므로, 회색 비소는 잘 부서지고 모스 굳기계에서 비교적 낮은 3.5의 경도를 가진다. 가장 가까운 형태와 다음으로 가장 가까운 형태는 왜곡된 팔면 복합체의 형태를 가지는데, 이것은 세 원자가 같은 이중 층에 있고 다음 층의 세 원자보다 약간 더 가까운 형태이다.[4] 비교적 가까운 형태의 이 충전물은 5.73g/cm3의 높은 밀도를 가지게 된다.[5] 회색 비소는 반금속이지만, 비정질일 경우 1.2–1.4 eV의 띠틈을 가진 반도체로 변한다.[6] 회색 비소는 또한 가장 안정적인 형태를 가지고 있다. 황색 비소는 부드럽고 납질이다. 또한 황색 비소는 테트라인(P

4)과 어느 정도 유사한 형태를 가지고 있다. 두 화합물은 한 원자가 다른 세 원자들과 결합하는 단일 결합 사면체의 구조로 이루어져 있다. 분자로 존재하는 이 불안정한 동소체들은, 가장 휘발성이 강하고, 밀도가 가장 적고, 가장 독성이 강하다. 고체 황색 비소는 As

4의 비소 증기를 빠르게 식히는 과정에서 생성된다. 이것은 빛을 받으면 빠른 속도로 회색 비소로 변한다. 황색 형태는 1.97 g/cm3의 밀도를 가진다.[5] 흑색 비소는 적린과 유사한 구조를 가진다.[5]

흑색 비소는 또한 100–220 °C의 온도에서 빠르게 비소 증기를 식힐 때 생성되기도 한다. 이것은 유리와 비슷하고 잘 부러진다. 또한 이것은 전기 전도가 잘 되지 않는다.[7]

동위 원소[편집]

비소는 안정된 동위 원소가 1개밖에 존재하지 않는 원소 중 하나다. 비소의 동위 원소 중 안정되었으면서 자연에 존재하는 동위 원소는 75As뿐이고, 다른 동위 원소는 합성된 것이다.[8] 2003년에는 적어도 33개의 방사성 동위 원소가 합성되었고, 원자량의 범위가 60에서 92까지 늘었다. 합성된 동위 원소 중 가장 안정한 동위 원소는 반감기가 80.3일인 73As이다. 이들을 제외한 동위 원소는 전부 반감기가 1일보다 적다. (그러나 71As부터 77As까지는 예외다[9]) 원자량이 75As보다 작은 동위 원소는 β+ 붕괴를 하고, 75As보다 큰 동위 원소는 β− 붕괴를 하지만, 일부 예외가 존재한다.

적어도 10개의 핵이성체가 만들어졌으며, 핵이성체가 존재하는 원자량의 범위가 66에서 84로 늘었다. 비소의 이성질체 중 가장 안정적인 것은 68mAs로 반감기가 111초이다.[8]

화학적 성질[편집]

비소는 3주기의 인과 유사한 전기음성도와 전리 에너지를 가지고 있으며 대부분의 비금속과 쉽게 공유 결합 분자의 구조를 띈다. 그렇지만 건조 공기에서 안정하며, 습한 장소에서의 비소는 금동색의 흐린 색을 띄고 표면에 검은 막이 생긴다.[10] 공기 중에서 가열할 경우, 비소는 삼산화 비소로 산화한다. 산화하는 과정 중 마늘과 비슷한 악취가 나는 유독성 기체를 생산한다. 이 악취는 황비철석을 망치로 부술 때와 같이 비화 광물을 부술 때 역시 생산된다.[11] 산소와 함께 반응하면 인의 잘 알려진 화합물들과 같은 구조인 삼산화 비소와 오산화 비소가 나오며, 플루오린과 반응하면 오플루오린화 비소가 나온다.[10] 비소(와 몇 비소 화합물)는 대기압에서 가열될 시 887 K (614 °C)에서 액체 과정을 거치지 않고 즉시 승화한다.[11] 삼중점은 3.63 MPa이자 1,090 K (820 °C)이다.[5][11] 비소는 농축된 질산과 만나면 비산을, 묽은 질산과 만나면 아비산을, 농축된 황산과 만나면 삼산화 비소를 만든다. 그러나, 물, 알칼리 금속, 산화되지 않는 산과는 반응하지 않는다.[12] 비소는 금속과 반응하면 비화물을 만들지만 As3− 이온을 형성하지 않고 높은 흡열성을 가진 음이온의 형태를 띈다. 또한 1족의 비화물은 합금의 성질을 가진다.[10] 저마늄, 셀레늄, 브로민과 같은 믈질들은 3d 전이금속으로 변하며, 비소는 5+ 이상의 형태를 띄면 같은 족에 위치한 인과 안티모니처럼 불안정해진다. 이로 인해 오산화 비소와 비산은 강한 산화제의 역할을 한다.[10]

화합물[편집]

비소의 화합물은 주기율표에서 같은 족에 위치한 인의 화합물과 유사성을 가진다. 그러나 비소는 오산화물이 인보다 잘 발견되지 않는다. 합금과 같은 금속 화합물인 비소화물 중 가장 흔한 산화수는 '-3', 아비산염 중에서 가장 흔한 산화수는 '+3', 비산염과 대부분의 유기비소 화합물 중에서 가장 흔한 산화수는 '+5'이다. 비소는 또한 스커털루다이트 광석에 존재하는 정사각형 형태의 As3-

4 이온을 보면 쉽게 결합한다는 것을 알 수 있다.[13] '+3' 산화 상태일 때, 비소는 고립 전자쌍의 형태를 띈 전자의 영향으로 보통 각뿔의 형태를 띈다.[3]

무기 화합물[편집]

이 문단에는 한국어로 번역되지 않은 내용이 담겨 있습니다. |

가장 간단한 비소 화합물 중 하나는 아르신으로 불리는 독성과 가연성이 강한 삼수소화물이다(AsH3). 이 화합물은 실온에서의 분해가 느리기 때문에 대부분 안정한 물질로 간주된다. 아르신은 250-300 °C의 온도에서 비소와 수소로의 분해가 빠르게 진행된다.[14] 습도, 빛의 유무 및 촉매(대표적으로 알루미늄)와 같은 여러 요소가 더해지면 아르신의 분해 속도를 촉진시킬 수 있다.[15] 아르신은 공기 중에서 금방 산화되어 삼산화 비소와 물을 형성하며, 산소와 같은 족에 위치한 황과 셀레늄으로도 이와 유사한 반응이 일어난다.[14]

비소는 무색, 무취의 결정질 산화물이자 흡습성이 있고 물에 용해되어 산성 용액을 형성하는 As2O3(비상)과 As2O5를 형성한다. 비산 (V)은 약산으로 염기 물질은 비산염(arsenate)이라 칭하며[16], 비산염은 가장 일반적인 비소 수질 오염 물질로 많은 사람들에게 피해을 끼치는 물질이다. 인공 합성된 비산염은 Paris Green(구리(II) 아세토아비산염), 비산 칼슘, 비산수소 납을 포함한다. 이 세 화합물은 농업 살충제와 독으로 사용된 적이 있다.

비산과 비산염 사이의 양성자화 단계는 인산과 인산염 사이의 양성자화 단계와 유사성을 보인다. 그와 달리, 아인산과 아비산은 As(OH)3과 같이 순수한 삼염기산 물질로 존재한다. [16]

비소의 황화합물은 많은 종류가 알려져 있다. 석황(As2S3)과 계관석(As4S4)이 주류이며, 이들은 도료로 사용되었다. As4S10에서의 비소와 비소-비소 결합의 특징이 담긴 As4S4에서 비소는 표면적으로 +2의 산화 상태를 이룬다. 그러므로 비소의 공유 결합 상태는 여전히 3의 상태에 머물러 있는 것을 알 수 있다.[17] As4S3 뿐만 아니라 석황과 계관석도 셀레늄 유사체를 가지고 있다; 그러나 텔루륨화 비소는 알려지지 않았으며, 음이온인 As2Te−은 코발트 복합체의 리간드로 알려져 있다.[18]

All trihalides of arsenic(III) are well known except the astatide, which is unknown. Arsenic pentafluoride (AsF5) is the only important pentahalide, reflecting the lower stability of the +5 oxidation state; even so, it is a very strong fluorinating and oxidizing agent. (The pentachloride is stable only below −50 °C, at which temperature it decomposes to the trichloride, releasing chlorine gas.[5])

합금[편집]

비소는 III-V 반도체 안에서 5족 원소로 사용된다. 대표적으로 비화 갈륨, 비화 인듐, 비화 알루미늄이 존재한다.[19] 비화 갈륨의 원자가는 규소와의 화합물과 같지만, 띠구조는 벌크 성질 등이 완전히 다르다.[20] 또다른 비소 합금은 II-V 반도체에 쓰이는 비화 카드뮴이다.[21]

유기비소 화합물[편집]

현재까지 많은 양의 유기비소 화합물이 알려져 있다. 몇몇은 제 1차 세계 대전에서 화학 무기로 만들어졌는데, 대표적으로 루이사이트와 같은 발포제나 애덤자이트와 같은 구토제에 주로 사용되었다.[22][23][24]카코딜산은 상당히 역사적으로 오래 쓰이고 실용적이다. 이것은 삼산화 비소가 메틸화되면서 발생한다. 삼산화 비소가 메틸화될 시 인의 화학적 성질과 유사한 점이 사라진다. 실제로, 카코딜은 유기금속 화합물 중 처음으로 알려졌으며, 다른 비소 화합물처럼 심한 악취가 남으로 인해 그리스어로 악취가 나는이라는 뜻을 가진 κακωδἰα에서 어원이 나왔다. 카코딜은 독성이 매우 강하다.[25]

존재와 생산[편집]

비소는 지각의 1.5 ppm (0.00015%)을 구성한다. 이는 53번째로 지각에 많이 존재하는 원소이다. Typical background concentrations are as follows: Air <3 ng m−3; soil <100 mg kg−1; freshwater <10 ug L−1; seawater <1.5 ug L−1.[26]

Minerals with the formula MAsS and MAs2 (M = Fe, Ni, Co) are the dominant commercial sources of arsenic, together with realgar (an arsenic sulfide mineral) and native arsenic. An illustrative mineral is arsenopyrite (FeAsS), which is structurally related to iron pyrite. Many minor As-containing minerals are known. Arsenic also occurs in various organic forms in the environment.[27]

In 2014, China was the top producer of white arsenic with almost 70% world share, followed by Morocco, Russia, and Belgium, according to the British Geological Survey and the United States Geological Survey.[29] Most arsenic refinement operations in the US and Europe have closed over environmental concerns. Arsenic is found of the smelter dust from copper, gold, and lead smelters, and is recovered primarily from copper refinement dust.[30]

On roasting arsenopyrite in air, arsenic sublimes as arsenic(III) oxide leaving iron oxides,[27] while roasting without air results in the production of metallic arsenic. Further purification from sulfur and other chalcogens is achieved by sublimation in vacuum, in a hydrogen atmosphere, or by distillation from molten lead-arsenic mixture.[31]

| 순위 | 국가 | 2014년 As2O3 생산량[29] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25,000 T | |

| 2 | 8,800 T | |

| 3 | 1,500 T | |

| 4 | 1,000 T | |

| 5 | 52 T | |

| 6 | 45 T | |

| — | 합계 (대략) | 36,400 T |

역사[편집]

비소의 영문인 arsenic은 시리아어의 ܠܐ ܙܐܦܢܝܐ (al) zarniqa가 시초이다.[32] 이것은 페르시아어의 زرنيخ zarnikh로 바뀌었는데, 황색을 의미하는 것이었다. (완전히 황금색의 노란색 (석황)). 이것은 그리스에 전파되어 arsenikon (ἀρσενικόν)으로 불리게 되어 이것이 민간 어원이 되었다. 이것은 arsenikos (ἀρσενικός)에서 나온 말로, 남성, 남성적인 의 뜻을 가지고 있다. 그리스어 arsenikos는 라틴에 전파되어 arsenicum으로 변화되었고, 프랑스에 전파되어 arsenic으로 변화되었다. 이렇게 해서 프랑스어 arsenic이 비소를 뜻하는 영어 단어가 되었다.[32] 황화 비소(석황, 계관석)와 산화 비소는 고대부터 알려졌고 사용되었다.[33] Zosimos는 (기원후 300년으로 추정)샌드락 (계관석)을 구워서 비소의 연기를 얻었다. (삼산화 비소) 요약하면 금속 비소를 산화하여 삼산화 비소를 만든 것이다.[34] 비소 중독의 증상은 표시가 잘 나지 않았기 때문에, 비소를 검출하는 화학 검사인 마시 시험이 나오기 전까지 주로 살해용으로 사용되었다. (덜 효과적이지만 더 잘 알려진 비소 검출 방법은 라인슈 시험이다.) 때문에 비소의 독성과 증상을 이용한 지배 계급이 서로를 독살하는 데 사용되었다. 이로 인해 비소는 "독의 왕" 또는 "왕의 독"으로 불렸다.[35]

청동기 시대 중, 비소는 청동을 단단하게 하기 위해 청동에 주로 들어갔다(그로 인해 이 합금은 "비소 청동"이라 불렸다.).[36][37] 알베르투스 마그누스(알베르트 대제, 1193년-1280년)는 1250년에 삼황화 비소와 비누를 같이 가열하여 비소를 화합물에서 원소로 처음으로 분리한 사람으로 알려져 있다.[38] 1649년에, 요한 슈뢰더는 비소를 얻는 2가지 방법을 발표했다.[39] 드물지만 비소 원소의 결정체가 자연에 존재하기도 하다.

Cadet's fuming liquid (impure cacodyl), often claimed as the first synthetic organometallic compound, was synthesized in 1760 by Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt by the reaction of potassium acetate with arsenic trioxide.[40]

In the Victorian era, "arsenic" ("white arsenic" or arsenic trioxide) was mixed with vinegar and chalk and eaten by women to improve the complexion of their faces, making their skin paler to show they did not work in the fields. Arsenic was also rubbed into the faces and arms of women to "improve their complexion". The accidental use of arsenic in the adulteration of foodstuffs led to the Bradford sweet poisoning in 1858, which resulted in around 20 deaths.[41]

Two arsenic pigments have been widely used since their discovery – Paris Green and Scheele's Green. After the toxicity of arsenic became widely known, these chemicals were used less often as pigments and more often as insecticides. In the 1860s, an arsenic byproduct of dye production, London Purple was widely used. This was a solid mixture of arsenic trioxide, aniline, lime, and ferrous oxide, insoluble in water and very toxic by inhalation or ingestion[42] But it was later replaced with Paris Green, another arsenic-based dye.[43] With better understanding of the toxicology mechanism, two other compounds were used starting in the 1890s.[44] Arsenite of lime and arsenate of lead were used widely as insecticides until the discovery of DDT in 1942.[45][46][47]

적용[편집]

농업적 이용[편집]

비소의 독성은 목재 가구에 곤충, 세균, 곰팡이 등을 억제하는 데 사용되었다.[48] In the 1950s, a process of treating wood with chromated copper arsenate (also known as CCA or Tanalith) was invented, and for decades, this treatment was the most extensive industrial use of arsenic. An increased appreciation of the toxicity of arsenic led to a ban of CCA in consumer products in 2004, initiated by the European Union and United States.[49][50] CCA remains in heavy use in other countries, however; e.g. Malaysian rubber plantations.[2]

Arsenic was also used in various agricultural insecticides and poisons. For example, lead hydrogen arsenate was a common insecticide on fruit trees,[51] but contact with the compound sometimes resulted in brain damage among those working the sprayers. In the second half of the 20th century, monosodium methyl arsenate (MSMA) and disodium methyl arsenate (DSMA) – less toxic organic forms of arsenic – have replaced lead arsenate in agriculture. With the exception of cotton farming, the use of the organic arsenicals was phased out until 2013.[52]

Arsenic is used as a feed additive in poultry and swine production, in particular in the U.S. to increase weight gain, improve feed efficiency, and to prevent disease.[53][54] An example is roxarsone, which had been used as a broiler starter by about 70% of U.S. broiler growers.[55] The Poison-Free Poultry Act of 2009 proposed to ban the use of roxarsone in industrial swine and poultry production.[56] Alpharma, a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc., which produces roxarsone, voluntarily suspended sales of the drug in response to studies showing elevated levels of inorganic arsenic, a carcinogen, in treated chickens.[57] A successor to Alpharma, Zoetis, continues to sell nitarsone, primarily for use in turkeys.[57]

Arsenic is intentionally added to the feed of chickens raised for human consumption. Organic arsenic compounds are less toxic than pure arsenic, and promote the growth of chickens. Under some conditions, the arsenic in chicken feed is converted to the toxic inorganic form.[58]

A 2006 study of the remains of the Australian racehorse, Phar Lap, determined that the 1932 death of the famous champion was caused by a massive overdose of arsenic. Sydney veterinarian Percy Sykes stated, "In those days, arsenic was quite a common tonic, usually given in the form of a solution (Fowler's Solution) ... It was so common that I'd reckon 90 per cent of the horses had arsenic in their system."[59]

의학적 이용[편집]

During the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, a number of arsenic compounds were used as medicines, including arsphenamine (by Paul Ehrlich) and arsenic trioxide (by Thomas Fowler).[60] Arsphenamine, as well as neosalvarsan, was indicated for syphilis and trypanosomiasis, but has been superseded by modern antibiotics.

Arsenic trioxide has been used in a variety of ways over the past 500 years, most commonly in the treatment of cancer, but in medications as diverse as Fowler's solution in psoriasis.[61] The US Food and Drug Administration in the year 2000 approved this compound for the treatment of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia that is resistant to all-trans retinoic acid.[62]

Recently, researchers have been locating tumors using arsenic-74 (a positron emitter). This isotope produces clearer PET scan images than the previous radioactive agent, iodine-124, because the body tends to transport iodine to the thyroid gland producing signal noise.[63]

In subtoxic doses, soluble arsenic compounds act as stimulants, and were once popular in small doses as medicine by people in the mid-18th to 19th centuries.[5]

합금 이용[편집]

The main use of metallic arsenic is in alloying with lead. Lead components in car batteries are strengthened by the presence of a very small percentage of arsenic.[2][64] Dezincification of brass (a copper-zinc alloy) is greatly reduced by the addition of arsenic.[65] "Phosphorus Deoxidized Arsenical Copper" with an arsenic content of 0.3% has an increased corrosion stability in certain environments.[66] Gallium arsenide is an important semiconductor material, used in integrated circuits. Circuits made from GaAs are much faster (but also much more expensive) than those made from silicon. Unlike silicon, GaAs has a direct bandgap, and can be used in laser diodes and LEDs to convert electrical energy directly into light.[2]

군사적 이용[편집]

After World War I, the United States built a stockpile of 20,000 tonnes of weaponized lewisite (ClCH=CHAsCl2), a vesicant (blister agent) and lung irritant. The stockpile was neutralized with bleach and dumped into the Gulf of Mexico after the 1950s.[67] During the Vietnam War, the United States used Agent Blue, a mixture of sodium cacodylate and its acid form, as one of the rainbow herbicides to deprive North Vietnamese soldiers of foliage cover and rice.[68][69]

기타 이용[편집]

- 아세토아비산구리는 파리 그린 (에메랄드 그린)을 포함한 녹색 안료로 쓰였으며, 이로 인해 수많은 비소 중독 환자를 만들어냈다. 아비산구리가 주성분인 셸레녹은 19세기에 사탕, 과자 등의 식용 색소로 쓰였다.[70]

- 비소는 변색제[71]와 신호탄에 쓰인다.

- 최대 2% 정도의 비소가 들어간 납 합금은 납 산탄이나 총알을 만드는 데 사용된다.[72]

- 탈아연 현상을 방지하기 위해 적은 양의 비소가 알파 황동에 들어가기도 한다. 이 종류의 황동은 배관 조정이나 다른 습한 환경에서 주로 쓰인다.[73]

- 분류학에서의 비소는 표본을 보존할 때 사용된다.

- 비소는 얼마전까지 광학 유리에 사용된 적이 있었다. 현대의 유리 제조업체들은 환경론자들의 압력으로 비소와 납의 사용을 중단했다.[74]

생물학적 역할[편집]

세균[편집]

Some species of bacteria obtain their energy by oxidizing various fuels while reducing arsenate to arsenite. Under oxidative environmental conditions some bacteria oxidize arsenite to arsenate as fuel for their metabolism.[75] The enzymes involved are known as arsenate reductases (Arr).[76]

In 2008, bacteria were discovered that employ a version of photosynthesis in the absence of oxygen with arsenites as electron donors, producing arsenates (just as ordinary photosynthesis uses water as electron donor, producing molecular oxygen). Researchers conjecture that, over the course of history, these photosynthesizing organisms produced the arsenates that allowed the arsenate-reducing bacteria to thrive. One strain PHS-1 has been isolated and is related to the gammaproteobacterium Ectothiorhodospira shaposhnikovii. The mechanism is unknown, but an encoded Arr enzyme may function in reverse to its known homologues.[77]

Although the arsenate and phosphate anions are similar structurally, no evidence exists for the replacement of phosphate in ATP or nucleic acids by arsenic.[78][79]

고등 동물의 필수 미량 원소[편집]

Some evidence indicates that arsenic is an essential trace mineral in birds (chickens), and in mammals (rats, hamsters, and goats). However, the biological function is not known.[80][81][82]

유전[편집]

Arsenic has been linked to epigenetic changes, heritable changes in gene expression that occur without changes in DNA sequence. These include DNA methylation, histone modification, and RNA interference. Toxic levels of arsenic cause significant DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes p16 and p53, thus increasing risk of carcinogenesis. These epigenetic events have been studied in vitro using human kidney cells and in vivo using rat liver cells and peripheral blood leukocytes in humans.[83] Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) is used to detect precise levels of intracellular arsenic and other arsenic bases involved in epigenetic modification of DNA.[84] Studies investigating arsenic as an epigenetic factor be used to develop precise biomarkers of exposure and susceptibility.

The Chinese brake fern (Pteris vittata) hyperaccumulates arsenic from the soil into its leaves and has a proposed use in phytoremediation.[85]

생체 메틸화[편집]

Inorganic arsenic and its compounds, upon entering the food chain, are progressively metabolized through a process of methylation.[86][87] For example, the mold Scopulariopsis brevicaulis produces significant amounts of trimethylarsine if inorganic arsenic is present.[88] The organic compound arsenobetaine is found in some marine foods such as fish and algae, and also in mushrooms in larger concentrations. The average person's intake is about 10–50 µg/day. Values about 1000 µg are not unusual following consumption of fish or mushrooms, but there is little danger in eating fish because this arsenic compound is nearly non-toxic.[89]

환경적 문제[편집]

노출[편집]

Naturally occurring sources of human exposure include volcanic ash, weathering of minerals and ores, and mineralized groundwater. Arsenic is also found in food, water, soil, and air.[90] Arsenic is absorbed by all plants, but is more concentrated in leafy vegetables, rice, apple and grape juice, and seafood.[91] An additional route of exposure is inhalation of atmospheric gases and dusts.[92]

식수 속에 존재하는 비소[편집]

Extensive arsenic contamination of groundwater has led to widespread arsenic poisoning in Bangladesh[93] and neighboring countries. It is estimated that approximately 57 million people in the Bengal basin are drinking groundwater with arsenic concentrations elevated above the World Health Organization's standard of 10 parts per billion (ppb).[94] However, a study of cancer rates in Taiwan[95] suggested that significant increases in cancer mortality appear only at levels above 150 ppb. The arsenic in the groundwater is of natural origin, and is released from the sediment into the groundwater, caused by the anoxic conditions of the subsurface. This groundwater was used after local and western NGOs and the Bangladeshi government undertook a massive shallow tube well drinking-water program in the late twentieth century. This program was designed to prevent drinking of bacteria-contaminated surface waters, but failed to test for arsenic in the groundwater. Many other countries and districts in Southeast Asia, such as Vietnam and Cambodia, have geological environments that produce groundwater with a high arsenic content. Arsenicosis was reported in Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand in 1987, and the Chao Phraya River probably contains high levels of naturally occurring dissolved arsenic without being a public health problem because much of the public uses bottled water.[96]

In the United States, arsenic is most commonly found in the ground waters of the southwest.[97] Parts of New England, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota and the Dakotas are also known to have significant concentrations of arsenic in ground water.[98] Increased levels of skin cancer have been associated with arsenic exposure in Wisconsin, even at levels below the 10 part per billion drinking water standard.[99] According to a recent film funded by the US Superfund, millions of private wells have unknown arsenic levels, and in some areas of the US, more than 20% of the wells may contain levels that exceed established limits.[100]

Low-level exposure to arsenic at concentrations of 100 parts per billion (i.e., above the 10 parts per billion drinking water standard) compromises the initial immune response to H1N1 or swine flu infection according to NIEHS-supported scientists. The study, conducted in laboratory mice, suggests that people exposed to arsenic in their drinking water may be at increased risk for more serious illness or death from the virus.[101]

Some Canadians are drinking water that contains inorganic arsenic. Private-dug–well waters are most at risk for containing inorganic arsenic. Preliminary well water analysis typically does not test for arsenic. Researchers at the Geological Survey of Canada have modeled relative variation in natural arsenic hazard potential for the province of New Brunswick. This study has important implications for potable water and health concerns relating to inorganic arsenic.[102]

Epidemiological evidence from Chile shows a dose-dependent connection between chronic arsenic exposure and various forms of cancer, in particular when other risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, are present. These effects have been demonstrated at contaminations less than 50 ppb.[103]

Analyzing multiple epidemiological studies on inorganic arsenic exposure suggests a small but measurable increase in risk for bladder cancer at 10 ppb.[104] According to Peter Ravenscroft of the Department of Geography at the University of Cambridge,[105] roughly 80 million people worldwide consume between 10 and 50 ppb arsenic in their drinking water. If they all consumed exactly 10 ppb arsenic in their drinking water, the previously cited multiple epidemiological study analysis would predict an additional 2,000 cases of bladder cancer alone. This represents a clear underestimate of the overall impact, since it does not include lung or skin cancer, and explicitly underestimates the exposure. Those exposed to levels of arsenic above the current WHO standard should weigh the costs and benefits of arsenic remediation.

Early (1973) evaluations of the processes for removing dissolved arsenic from drinking water demonstrated the efficacy of co-precipitation with either iron or aluminum oxides. In particular, iron as a coagulant was found to remove arsenic with an efficacy exceeding 90%.[106][107] Several adsorptive media systems have been approved for use at point-of-service in a study funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). A team of European and Indian scientists and engineers have set up six arsenic treatment plants in West Bengal based on in-situ remediation method (SAR Technology). This technology does not use any chemicals and arsenic is left in an insoluble form (+5 state) in the subterranean zone by recharging aerated water into the aquifer and developing an oxidation zone that supports arsenic oxidizing micro-organisms. This process does not produce any waste stream or sludge and is relatively cheap.[108]

Another effective and inexpensive method to avoid arsenic contamination is to sink wells 500 feet or deeper to reach purer waters. A recent 2011 study funded by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences' Superfund Research Program shows that deep sediments can remove arsenic and take it out of circulation. In this process, called adsorption, arsenic sticks to the surfaces of deep sediment particles and is naturally removed from the ground water.[109]

Magnetic separations of arsenic at very low magnetic field gradients with high-surface-area and monodisperse magnetite (Fe3O4) nanocrystals have been demonstrated in point-of-use water purification. Using the high specific surface area of Fe3O4 nanocrystals, the mass of waste associated with arsenic removal from water has been dramatically reduced.[110]

Epidemiological studies have suggested a correlation between chronic consumption of drinking water contaminated with arsenic and the incidence of all leading causes of mortality.[111] The literature indicates that arsenic exposure is causative in the pathogenesis of diabetes.[112]

Chaff-based filters have recently been shown to reduce the arsenic content of water to 3 µg/L. This may find applications in areas where the potable water is extracted from underground aquifers.[113]

산 페드로 데 아타카마[편집]

For several centuries, the people of 산페드로데아타카마 in Chile have been drinking water that is contaminated with arsenic, and some evidence suggests they have developed some immunity.[114][115][116]

자연에 존재하는 물 중의 비소의 산화 환원 반응[편집]

Arsenic is unique among the trace metalloids and oxyanion-forming trace metals (e.g. As, Se, Sb, Mo, V, Cr, U, Re). It is sensitive to mobilization at pH values typical of natural waters (pH 6.5–8.5) under both oxidizing and reducing conditions. Arsenic can occur in the environment in several oxidation states (−3, 0, +3 and +5), but in natural waters it is mostly found in inorganic forms as oxyanions of trivalent arsenite [As(III)] or pentavalent arsenate [As(V)]. Organic forms of arsenic are produced by biological activity, mostly in surface waters, but are rarely quantitatively important. Organic arsenic compounds may, however, occur where waters are significantly impacted by industrial pollution.[117]

Arsenic may be solubilized by various processes. When pH is high, arsenic may be released from surface binding sites that lose their positive charge. When water level drops and sulfide minerals are exposed to air, arsenic trapped in sulfide minerals can be released into water. When organic carbon is present in water, bacteria are fed by directly reducing As(V) to As(III) or by reducing the element at the binding site, releasing inorganic arsenic.[118]

The aquatic transformations of arsenic are affected by pH, reduction-oxidation potential, organic matter concentration and the concentrations and forms of other elements, especially iron and manganese. The main factors are pH and the redox potential. Generally, the main forms of arsenic under oxic conditions are H3AsO4, H2AsO4−, HAsO42−, and AsO43− at pH 2, 2–7, 7–11 and 11, respectively. Under reducing conditions, H3AsO4 is predominant at pH 2–9.

Oxidation and reduction affects the migration of arsenic in subsurface environments. Arsenite is the most stable soluble form of arsenic in reducing environments and arsenate, which is less mobile than arsenite, is dominant in oxidizing environments at neutral pH. Therefore, arsenic may be more mobile under reducing conditions. The reducing environment is also rich in organic matter which may enhance the solubility of arsenic compounds. As a result, the adsorption of arsenic is reduced and dissolved arsenic accumulates in groundwater. That is why the arsenic content is higher in reducing environments than in oxidizing environments.[119]

The presence of sulfur is another factor that affects the transformation of arsenic in natural water. Arsenic can precipitate when metal sulfides form. In this way, arsenic is removed from the water and its mobility decreases. When oxygen is present, bacteria oxidize reduced sulfur to generate energy, potentially releasing bound arsenic.

Redox reactions involving Fe also appear to be essential factors in the fate of arsenic in aquatic systems. The reduction of iron oxyhydroxides plays a key role in the release of arsenic to water. So arsenic can be enriched in water with elevated Fe concentrations.[120] Under oxidizing conditions, arsenic can be mobilized from pyrite or iron oxides especially at elevated pH. Under reducing conditions, arsenic can be mobilized by reductive desorption or dissolution when associated with iron oxides. The reductive desorption occurs under two circumstances. One is when arsenate is reduced to arsenite which adsorbs to iron oxides less strongly. The other results from a change in the charge on the mineral surface which leads to the desorption of bound arsenic.[121]

Some species of bacteria catalyze redox transformations of arsenic. Dissimilatory arsenate-respiring prokaryotes (DARP) speed up the reduction of As(V) to As(III). DARP use As(V) as the electron acceptor of anaerobic respiration and obtain energy to survive. Other organic and inorganic substances can be oxidized in this process. Chemoautotrophic arsenite oxidizers (CAO) and heterotrophic arsenite oxidizers (HAO) convert As(III) into As(V). CAO combine the oxidation of As(III) with the reduction of oxygen or nitrate. They use obtained energy to fix produce organic carbon from CO2. HAO cannot obtain energy from As(III) oxidation. This process may be an arsenic detoxification mechanism for the bacteria.[122]

Equilibrium thermodynamic calculations predict that As(V) concentrations should be greater than As(III) concentrations in all but strongly reducing conditions, i.e. where SO42− reduction is occurring. However, abiotic redox reactions of arsenic are slow. Oxidation of As(III) by dissolved O2 is a particularly slow reaction. For example, Johnson and Pilson (1975) gave half-lives for the oxygenation of As(III) in seawater ranging from several months to a year.[123] In other studies, As(V)/As(III) ratios were stable over periods of days or weeks during water sampling when no particular care was taken to prevent oxidation, again suggesting relatively slow oxidation rates. Cherry found from experimental studies that the As(V)/As(III) ratios were stable in anoxic solutions for up to 3 weeks but that gradual changes occurred over longer timescales.[124] Sterile water samples have been observed to be less susceptible to speciation changes than non-sterile samples.[125] Oremland found that the reduction of As(V) to As(III) in Mono Lake was rapidly catalyzed by bacteria with rate constants ranging from 0.02 to 0.3 day−1.[126]

미국에서의 나무 보전[편집]

As of 2002, US-based industries consumed 19,600 metric tons of arsenic. Ninety percent of this was used for treatment of wood with chromated copper arsenate (CCA). In 2007, 50% of the 5,280 metric tons of consumption was still used for this purpose.[30][127] In the United States, the voluntary phasing-out of arsenic in production of consumer products and residential and general consumer construction products began on 31 December 2003, and alternative chemicals are now used, such as Alkaline Copper Quaternary, borates, copper azole, cyproconazole, and propiconazole.[128]

Although discontinued, this application is also one of the most concern to the general public. The vast majority of older pressure-treated wood was treated with CCA. CCA lumber is still in widespread use in many countries, and was heavily used during the latter half of the 20th century as a structural and outdoor building material. Although the use of CCA lumber was banned in many areas after studies showed that arsenic could leach out of the wood into the surrounding soil (from playground equipment, for instance), a risk is also presented by the burning of older CCA timber. The direct or indirect ingestion of wood ash from burnt CCA lumber has caused fatalities in animals and serious poisonings in humans; the lethal human dose is approximately 20 grams of ash.[출처 필요] Scrap CCA lumber from construction and demolition sites may be inadvertently used in commercial and domestic fires. Protocols for safe disposal of CCA lumber are not consistent throughout the world. Widespread landfill disposal of such timber raises some concern,[129] but other studies have shown no arsenic contamination in the groundwater.[130][131]

Mapping of industrial releases in the US[편집]

One tool that maps the location (and other information) of arsenic releases in the United State is TOXMAP.[132] TOXMAP is a Geographic Information System (GIS) from the Division of Specialized Information Services of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) funded by the US Federal Government. With marked-up maps of the United States, TOXMAP enables users to visually explore data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory and Superfund Basic Research Programs. TOXMAP's chemical and environmental health information is taken from NLM's Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET),[133] PubMed, and from other authoritative sources.

Bioremediation[편집]

Physical, chemical, and biological methods have been used to remediate arsenic contaminated water.[134] Bioremediation is said to be cost effective and environmentally friendly[135] Bioremediation of ground water contaminated with arsenic aims to convert arsenite, the toxic form of arsenic to humans, to arsenate. Arsenate (+5 oxidation state) is the dominant form of arsenic in surface water, while arsenite (+3 oxidation state) is the dominant form in hypoxic to anoxic environments. Arsenite is more soluble and mobile than arsenate. Many species of bacteria can transform arsenite to arsenate in anoxic conditions by using arsenite as an electron donor.[136] This is a useful method in ground water remediation. Another bioremediation strategy is to use plants that accumulate arsenic in their tissues via phytoremediation but the disposal of contaminated plant material needs to be considered.

Bioremediation requires careful evaluation and design in accordance with existing conditions. Some sites may require the addition of an electron acceptor while others require microbe supplementation (bioaugmentation). Regardless of the method used, only constant monitoring can prevent future contamination.

Toxicity and precautions[편집]

Arsenic and many of its compounds are especially potent poisons.

Classification[편집]

Elemental arsenic and arsenic compounds are classified as "toxic" and "dangerous for the environment" in the European Union under directive 67/548/EEC. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recognizes arsenic and arsenic compounds as group 1 carcinogens, and the EU lists arsenic trioxide, arsenic pentoxide, and arsenate salts as category 1 carcinogens.

Arsenic is known to cause arsenicosis when present in drinking water, "the most common species being arsenate [HAsO2−

4; As(V)] and arsenite [H3AsO3; As(III)]".

Legal limits, food, and drink[편집]

In the United States since 2006, the maximum concentration in drinking water allowed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is 10 ppb[137] and the FDA set the same standard in 2005 for bottled water.[138][139]틀:Unreliable source? The Department of Environmental Protection for New Jersey set a drinking water limit of 5 ppb in 2006.[140] The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value for arsenic metal and inorganic arsenic compounds is 5 mg/m3. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set the permissible exposure limit (PEL) to a time-weighted average (TWA) of 0.01 mg/m3, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set the recommended exposure limit (REL) to a 15-minute constant exposure of 0.002 mg/m3.[141] The PEL for organic arsenic compounds is a TWA of 0.5 mg/m3.[142]

In 2008, based on its ongoing testing of a wide variety of American foods for toxic chemicals,[143] the U.S. Food and Drug Administration set the "level of concern" for inorganic arsenic apple and pear juices at 23 ppb, based on non-carcinogenic effects, and began blocking importation of products in excess of this level; it also required recalls for non-conforming domestic products.[138] In 2011, the national Dr. Oz television show broadcast a program highlighting tests performed by an independent lab hired by the producers. Though the methodology was disputed (it did not distinguish between organic and inorganic arsenic) the tests showed levels of arsenic up to 36 ppb.[144] In response, FDA tested the worst brand from the Dr. Oz show and found much lower levels. Ongoing testing found 95% of the apple juice samples were below the level of concern. Later testing by Consumer Reports showed inorganic arsenic at levels slightly above 10 ppb, and the organization urged parents to reduce consumption.[145] In July 2013, on consideration of consumption by children, chronic exposure, and carcinogenic effect, the FDA established an "action level" of 10 ppb for apple juice, the same as the drinking water standard.[138]

Concern about arsenic in rice in Bangladesh was raised in 2002, but at the time only Australia had a legal limit for food (one milligram per kilogram).[146][147] Concern was raised about people who were eating U.S. rice exceeding WHO standards for personal arsenic intake in 2005.[148] In 2011, the People's Republic of China set a food standard of 150 ppb for arsenic.[149]

In the United States in 2012, testing by separate groups of researchers at the Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center at Dartmouth College (early in the year, focusing on urinary levels in children)[150] and Consumer Reports (in November)[151][152] found levels of arsenic in rice that resulted in calls for the FDA to set limits.[139] The FDA released some testing results in September 2012,[153][154] and as of July 2013, is still collecting data in support of a new potential regulation. It has not recommended any changes in consumer behavior.[155]

Consumer Reports recommended:

- That the EPA and FDA eliminate arsenic-containing fertilizer, drugs, and pesticides in food production;

- That the FDA establish a legal limit for food;

- That industry change production practices to lower arsenic levels, especially in food for children; and

- That consumers test home water supplies, eat a varied diet, and cook rice with excess water, then draining it off (reducing inorganic arsenic by about one third along with a slight reduction in vitamin content).[152]

- Evidence-based public health advocates also recommend that, given the lack of regulation or labeling for arsenic in the U.S., children should eat no more than 1.5 servings per week of rice and should not drink rice milk as part of their daily diet before age 5.[156] They also offer recommendations for adults and infants on how to limit arsenic exposure from rice, drinking water, and fruit juice.[156]

A 2014 World Health Organization advisory conference was scheduled to consider limits of 200–300 ppb for rice.[152]

작업 노출 한계[편집]

| 국가 | 한계[157] |

|---|---|

| 아르헨티나 | 발암 물질 |

| 호주 | TWA 0.05 mg/m3미만 |

| 벨기에 | TWA 0.1 mg/m3미만 |

| 불가리아 | 발암 물질 |

| 콜롬비아 | 발암 물질 |

| 덴마크 | TWA 0.01 mg/m3미만 |

| 핀란드 | 발암 물질 |

| 이집트 | TWA 0.2 mg/m3미만 |

| 헝가리 | 피부에 최대 0.01 mg/m3, 발암 물질 |

| 인도 | TWA 0.2 mg/m3미만 |

| 일본 | 1군 발암 물질 |

| 요르단 | 발암 물질 |

| 멕시코 | TWA 0.2 mg/m3미만 |

| 뉴질랜드 | TWA 0.05 mg/m3미만, 발암 물질 |

| 노르웨이 | TWA 0.02 mg/m3미만 |

| 필리핀 | TWA 0.5 mg/m3미만 |

| 폴란드 | TWA 0.01 mg/m3미만 |

| 싱가포르 | 발암 물질 |

| 대한민국 | TWA 0.01 mg/m3미만[158][159] |

| 스웨덴 | TWA 0.01 mg/m3미만 |

| 태국 | TWA 0.5 mg/m3미만 |

| 터키 | TWA 0.5 mg/m3미만 |

| 영국 | TWA 0.1 mg/m3미만 |

| 미국 | TWA 0.01 mg/m3미만 |

| 베트남 | 발암 물질 |

생태독성[편집]

비소는 bioaccumulative in many organisms, marine species in particular, but it does not appear to biomagnify significantly in food webs. In polluted areas, plant growth may be affected by root uptake of arsenate, which is a phosphate analog and therefore readily transported in plant tissues and cells. In polluted areas, uptake of the more toxic arsenite ion (found more particularly in reducing conditions) is likely in poorly-drained soils.[26]

동물한테의 독성[편집]

| 화합물 | 동물 | LD50 | 경로 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 비소 | 쥐 | 763 mg/kg | 입 |

| 비소 | 쥐 | 145 mg/kg | 입 |

| 비산칼슘 | 쥐 | 20 mg/kg | 입 |

| 비산칼슘 | 쥐 | 794 mg/kg | 입 |

| 비산칼슘 | 토끼 | 50 mg/kg | 입 |

| 비산칼슘 | 개 | 38 mg/kg | 입 |

| 비산납 | 토끼 | 75 mg/kg | 입 |

| 화합물 | 동물 | LD50[160] | 경로 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 삼산화 비소 (As(III)) | 쥐 | 26 mg/kg | 입 |

| 아비산염 (As(III)) | 쥐 | 8 mg/kg | im |

| 비산염 (As(V)) | 쥐 | 21 mg/kg | im |

| MMA (As(III)) | 햄스터 | 2 mg/kg | ip |

| MMA (As(V)) | 쥐 | 916 mg/kg | 입 |

| DMA (As(V)) | 쥐 | 648 mg/kg | 입 |

| im = 근육 내 주사

ip = 복강 내 주사 | |||

Biological mechanism[편집]

Arsenic's toxicity comes from the affinity of arsenic(III) oxides for thiols. Thiols, in the form of cysteine residues and cofactors such as lipoic acid and coenzyme A, are situated at the active sites of many important enzymes.[2]

Arsenic disrupts ATP production through several mechanisms. At the level of the citric acid cycle, arsenic inhibits lipoic acid, which is a cofactor for pyruvate dehydrogenase. By competing with phosphate, arsenate uncouples oxidative phosphorylation, thus inhibiting energy-linked reduction of NAD+, mitochondrial respiration and ATP synthesis. Hydrogen peroxide production is also increased, which, it is speculated, has potential to form reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress. These metabolic interferences lead to death from multi-system organ failure. The organ failure is presumed to be from necrotic cell death, not apoptosis, since energy reserves have been too depleted for apoptosis to occur.[160]

Although arsenic causes toxicity it can also play a protective role.[161]

Exposure risks and remediation[편집]

Occupational exposure and arsenic poisoning may occur in persons working in industries involving the use of inorganic arsenic and its compounds, such as wood preservation, glass production, nonferrous metal alloys, and electronic semiconductor manufacturing. Inorganic arsenic is also found in coke oven emissions associated with the smelter industry.[162]

The conversion between As(III) and As(V) is a large factor in arsenic environmental contamination. According to Croal, Gralnick, Malasarn and Newman, "[the] understanding [of] what stimulates As(III) oxidation and/or limits As(V) reduction is relevant for bioremediation of contaminated sites (Croal). The study of chemolithoautotrophic As(III) oxidizers and the heterotrophic As(V) reducers can help the understanding of the oxidation and/or reduction of arsenic.[163] It has been proposed that As(III) which is more toxic than Arsenic (V) can be removed from the ground water using baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[164]

Treatment[편집]

Treatment of chronic arsenic poisoning is possible. British anti-lewisite (dimercaprol) is prescribed in doses of 5 mg/kg up to 300 mg every 4 hours for the first day, then every 6 hours for the second day, and finally every 8 hours for 8 additional days.[165] However the USA's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) states that the long-term effects of arsenic exposure cannot be predicted.[92] Blood, urine, hair, and nails may be tested for arsenic; however, these tests cannot foresee possible health outcomes from the exposure.[92] Long-term exposure and consequent excretion through urine has been linked to bladder and kidney cancer in addition to cancer of the liver, prostate, skin, lungs, and nasal cavity.[166]

더 보기[편집]

이 문단은 아직 미완성입니다. 여러분의 지식으로 알차게 문서를 완성해 갑시다. |

주석[편집]

- ↑ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 81th edition, CRC press.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 Grund, Sabina C.; Hanusch, Kunibert; Wolf, Hans Uwe, 〈Arsenic and Arsenic Compounds〉, 《울만 공업화학 백과사전(Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry)》, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_113.pub2

- ↑ 가 나 Norman, Nicholas C (1998). 《Chemistry of Arsenic, Antimony and Bismuth》. Springer. 50쪽. ISBN 978-0-7514-0389-3.

- ↑ Biberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils; Holleman, Arnold Frederick (2001). 《Inorganic Chemistry》. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). 〈Arsen〉. 《Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie》 (독일어) 91–100판. Walter de Gruyter. 675–681쪽. ISBN 3-11-007511-3.

- ↑ Madelung, Otfried (2004). 《Semiconductors: data handbook》. Birkhäuser. 410–쪽. ISBN 978-3-540-40488-0.

- ↑ Arsenic Element Facts. chemicool.com

- ↑ 가 나 Georges, Audi; Bersillon, O.; Blachot, J.; Wapstra, A.H. (2003). “The NUBASE Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties”. 《Nuclear Physics A》 (Atomic Mass Data Center) 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ↑ 71As부터 나열하면 t1/2=65.3시간, t1/2=26.0시간, t1/2=80.3일, t1/2=17.77일, (75As는 안정된 동위 원소이다.), t1/2=26.4시간, t1/2=38.8시간의 반감기를 가진다.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 552–4

- ↑ 가 나 다 인용 오류:

<ref>태그가 잘못되었습니다;Gokcen1989라는 이름을 가진 주석에 텍스트가 없습니다 - ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Arsenic〉. 《브리태니커 백과사전》 2 11판. 케임브리지 대학교 출판부. 651–654쪽.

Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Arsenic〉. 《브리태니커 백과사전》 2 11판. 케임브리지 대학교 출판부. 651–654쪽.

- ↑ Uher, Ctirad (2001). “Recent Trends in Thermoelectric Materials Research I: Skutterudites: Prospective novel thermoelectrics”. 《Semiconductors and Semimetals》 69: 139–253. doi:10.1016/S0080-8784(01)80151-4. ISBN 978-0-12-752178-7.

- ↑ 가 나 Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 557–8

- ↑ Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité (2000). “Fiche toxicologique nº 53: Trihydrure d'arsenic” (PDF). 2006년 9월 6일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 572–8

- ↑ “Arsenic: arsenic(II) sulfide compound data”. WebElements.com. 2007년 12월 11일에 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 578–83

- ↑ Tanaka, A (2004). “Toxicity of indium arsenide, gallium arsenide, and aluminium gallium arsenide”. 《Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology》 198 (3): 405–11. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.10.019. PMID 15276420.

- ↑ Ossicini, Stefano; Pavesi, Lorenzo; Priolo, Francesco (2003년 1월 1일). 《Light Emitting Silicon for Microphotonics》. ISBN 978-3-540-40233-6. 2013년 9월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ Din, M.B.; Gould, R.D. (1998). “High field conduction mechanism of the evaporated cadmium arsenide thin films”. 《ICSE'98. 1998 IEEE International Conference on Semiconductor Electronics. Proceedings (Cat. No.98EX187)》: 168. doi:10.1109/SMELEC.1998.781173. ISBN 0-7803-4971-7.

- ↑ Ellison, Hank D. (2007). 《Handbook of chemical and biological warfare agents》. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-1434-6.

- ↑ Girard, James (2010). 《Principles of Environmental Chemistry》. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-5939-1.

- ↑ Somani, Satu M (2001). 《Chemical warfare agents: toxicity at low levels》. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0872-7.

- ↑ Greenwood, p. 584

- ↑ 가 나 Rieuwerts, John. [1], The Elements of Environmental Pollution, Routledge, Abingdon and New York, 2015.

- ↑ 가 나 Matschullat, Jörg (2000). “Arsenic in the geosphere — a review”. 《The Science of the Total Environment》 249 (1–3): 297–312. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00524-0. PMID 10813460.

- ↑ Brooks, William E. “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2007: Arsenic” (PDF). United States Geological Survey. 2008년 12월 17일에 보존된 문서 (PDF). 2008년 11월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Edelstein, Daniel L. “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2016: Arsenic” (PDF). United States Geological Survey. 2016년 7월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Brooks, William E. “Minerals Yearbook 2007: Arsenic” (PDF). United States Geological Survey. 2008년 12월 17일에 보존된 문서 (PDF). 2008년 11월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Whelan, J. M.; Struthers, J. D.; Ditzenberger, J. A. (1960). “Separation of Sulfur, Selenium, and Tellurium from Arsenic”. 《Journal of the Electrochemical Society》 107 (12): 982–985. doi:10.1149/1.2427585.

- ↑ 가 나 “arsenic”. Online Etymology Dictionary. 2010년 5월 15일에 확인함.

- ↑ Bentley, Ronald; Chasteen, Thomas G. (2002). “Arsenic Curiosa and Humanity”. 《The Chemical Educator》 7 (2): 51–60.

- ↑ Holmyard John Eric (2007). 《Makers of Chemistry》. Read Books. ISBN 1-4067-3275-3.

- ↑ Vahidnia, A.; Van Der Voet, G. B.; De Wolff, F. A. (2007). “Arsenic neurotoxicity – a review”. 《Human & Experimental Toxicology》 26 (10): 823–32. doi:10.1177/0960327107084539. PMID 18025055.

- ↑ Lechtman, H. (1996). “Arsenic Bronze: Dirty Copper or Chosen Alloy? A View from the Americas”. 《Journal of Field Archaeology》 23 (4): 477–514. doi:10.2307/530550. JSTOR 530550.

- ↑ Charles, J. A. (1967). “Early Arsenical Bronzes-A Metallurgical View”. 《American Journal of Archaeology》 71 (1): 21–26. doi:10.2307/501586. JSTOR 501586.

- ↑ Emsley, John (2001). 《Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements》. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 43, 513, 529쪽. ISBN 0-19-850341-5.

- ↑ (Comte), Antoine-François de Fourcroy (1804). 《A general system of chemical knowledge, and its application to the phenomena of nature and art》. 84–쪽.

- ↑ Seyferth, Dietmar (2001). “Cadet's Fuming Arsenical Liquid and the Cacodyl Compounds of Bunsen”. 《Organometallics》 20 (8): 1488–1498. doi:10.1021/om0101947.

- ↑ Turner, Alan (1999). “Viewpoint: the story so far: An overview of developments in UK food regulation and associated advisory committees”. 《British Food Journal》 101 (4): 274–283. doi:10.1108/00070709910272141.

- ↑ "London purple. (8012-74-6)", Chemical Book

- ↑ Lanman, Susan W. (2000). “Colour in the Garden: 'Malignant Magenta'”. 《Garden History》 28 (2): 209–221. doi:10.2307/1587270. JSTOR 1587270.

- ↑ Holton, E. C. (1926). “Insecticides and Fungicides”. 《Industrial & Engineering Chemistry》 18 (9): 931–933. doi:10.1021/ie50201a018.

- ↑ Murphy, E.A.; Aucott, M (1998). “An assessment of the amounts of arsenical pesticides used historically in a geographical area”. 《Science of the Total Environment》 218 (2–3): 89–101. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00180-6.

- ↑ Marlatt, C. L (1897). 《Important Insecticides: Directions for Their Preparation and Use》. 5쪽.

- ↑ Kassinger, Ruth (2010년 4월 20일). 《Paradise Under Glass: An Amateur Creates a Conservatory Garden》. ISBN 978-0-06-199130-1.

- ↑ Rahman, FA; Allan, DL; Rosen, CJ; Sadowsky, MJ (2004). “Arsenic availability from chromated copper arsenate (CCA)-treated wood”. 《Journal of Environmental Quality》 33 (1): 173–80. doi:10.2134/jeq2004.0173. PMID 14964372.

- ↑ Lichtfouse, Eric (2004). 〈Electrodialytical Removal of Cu, Cr and As from Threaded Wood〉. Lichtfouse, Eric; Schwarzbauer, Jan; Robert, Didier. 《Environmental Chemistry: Green Chemistry and Pollutants in Ecosystems》. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-22860-8.

- ↑ Mandal, Badal Kumar; Suzuki, K. T. (2002). “Arsenic round the world: a review”. 《Talanta》 58 (1): 201–235. doi:10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00268-0. PMID 18968746.

- ↑ Peryea, F. J. (1998년 8월 26일). 《Historical use of lead arsenate insecticides, resulting in soil contamination and implications for soil remediation》. 16th World Congress of Soil Science. Montpellier, France.

- ↑ “organic arsenicals”. EPA.

- ↑ Nachman, Keeve E; Graham, Jay P.; Price, Lance B.; Silbergeld, Ellen K. (2005). “Arsenic: A Roadblock to Potential Animal Waste Management Solutions”. 《Environmental Health Perspectives》 113 (9): 1123–1124. doi:10.1289/ehp.7834.

- ↑ “Arsenic” (PDF). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Section 5.3, p. 310.

- ↑ Jones, F. T. (2007). “A Broad View of Arsenic”. 《Poultry Science》 86 (1): 2–14. doi:10.1093/ps/86.1.2. PMID 17179408.

- ↑ Bottemiller, Helena (2009년 9월 26일). “Bill Introduced to Ban Arsenic Antibiotics in Feed”. 《Food Safety News》. 2011년 1월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Staff (2011년 6월 8일). “Questions and Answers Regarding 3-Nitro (Roxarsone)”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2012년 9월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gray, Theodore (2012년 4월 3일). 〈Arsenic〉. Gray, Theodore; Mann, Nick. 《Elements: A Visual Exploration of Every Known Atom in the Universe》. Hachette Books. ISBN 1579128955.

- ↑ “Phar Lap arsenic claims premature: expert”. 《ABC News-AU》. 2006년 10월 23일. 2016년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gibaud, Stéphane; Jaouen, Gérard (2010). “Arsenic – based drugs: from Fowler's solution to modern anticancer chemotherapy”. 《Topics in Organometallic Chemistry》. Topics in Organometallic Chemistry 32: 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13185-1_1. ISBN 978-3-642-13184-4.

- ↑ Huet, P. M.; Guillaume, E.; Cote, J.; Légaré, A.; Lavoie, P.; Viallet, A. (1975). “Noncirrhotic presinusoidal portal hypertension associated with chronic arsenical intoxication”. 《Gastroenterology》 68 (5 Pt 1): 1270–1277. PMID 1126603.

- ↑ Antman, Karen H. (2001). “The History of Arsenic Trioxide in Cancer Therapy”. 《The oncologist》 6 (Suppl 2): 1–2. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_2-1. PMID 11331433.

- ↑ Jennewein, Marc; Lewis, M. A.; Zhao, D.; Tsyganov, E.; Slavine, N.; He, J.; Watkins, L.; Kodibagkar, V. D.; O'Kelly, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Antich, P.; Hermanne, A.; Rösch, F.; Mason, R.; Thorpe, Ph. (2008). “Vascular Imaging of Solid Tumors in Rats with a Radioactive Arsenic-Labeled Antibody that Binds Exposed Phosphatidylserine”. 《Journal of Clinical Cancer》 14 (5): 1377–1385. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1516. PMC 3436070. PMID 18316558.

- ↑ Bagshaw, N.E. (1995). “Lead alloys: Past, present and future”. 《Journal of Power Sources》 53: 25–30. Bibcode:1995JPS....53...25B. doi:10.1016/0378-7753(94)01973-Y.

- ↑ Joseph, Günter; Kundig, Konrad J. A; Association, International Copper (1999). 〈Dealloying〉. 《Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status》. 123–124쪽. ISBN 978-0-87170-656-0.

- ↑ Nayar (1997). 《The Metals Databook》. 6쪽. ISBN 978-0-07-462300-8.

- ↑ “Blister Agents”. Code Red – Weapons of Mass Destruction. 2010년 5월 15일에 확인함.

- ↑ Westing, Arthur H. (1972). “Herbicides in war: Current status and future doubt”. 《Biological Conservation》 4 (5): 322–327. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(72)90043-2.

- ↑ Westing, Arthur H. (1971). “Forestry and the War in South Vietnam”. 《Journal of Forestry》 69: 777–783.

- ↑ Timbrell, John (2005). 〈Butter Yellow and Scheele's Green〉. 《The Poison Paradox: Chemicals as Friends and Foes》. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280495-2.

- ↑ Cross, J. D.; Dale, I. M.; Leslie, A. C. D.; Smith, H. (1979). “Industrial exposure to arsenic”. 《Journal of Radioanalytical Chemistry》 48: 197–208. doi:10.1007/BF02519786.

- ↑ Guruswamy, Sivaraman (1999). 〈XIV. Ammunition〉. 《Engineering Properties and Applications of Lead Alloys》. CRC Press. 569–570쪽. ISBN 978-0-8247-8247-4.

- ↑ Davis, Joseph R; Handbook Committee, ASM International (2001년 8월 1일). 〈Dealloying〉. 《Copper and copper alloys》. 390쪽. ISBN 978-0-87170-726-0.

- ↑ 〈Arsenic Supply Demand and the Environment〉. 《Pollution technology review 214: Mercury and arsenic wastes: removal, recovery, treatment, and disposal》. William Andrew. 1993. 68쪽. ISBN 978-0-8155-1326-1.

- ↑ Stolz, John F.; Basu, Partha; Santini, Joanne M.; Oremland, Ronald S. (2006). “Arsenic and Selenium in Microbial Metabolism”. 《Annual Review of Microbiology》 60: 107–30. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142053. PMID 16704340.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay, Rita; Rosen, Barry P; Phung, Le T; Silver, Simon (2002). “Microbial arsenic: From geocycles to genes and enzymes”. 《FEMS Microbiology Reviews》 26 (3): 311–25. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00617.x. PMID 12165430.

- ↑ Kulp, T. R; Hoeft, S. E.; Asao, M.; Madigan, M. T.; Hollibaugh, J. T.; Fisher, J. C.; Stolz, J. F.; Culbertson, C. W.; Miller, L. G.; Oremland, R. S. (2008). “Arsenic(III) fuels anoxygenic photosynthesis in hot spring biofilms from Mono Lake, California”. 《Science》 321 (5891): 967–970. Bibcode:2008Sci...321..967K. doi:10.1126/science.1160799. PMID 18703741. 요약문 – Chemistry World, 15 August 2008.

- ↑ Erb, T. J.; Kiefer, P.; Hattendorf, B.; Günther, D.; Vorholt, J. A. (2012). “GFAJ-1 is an Arsenate-Resistant, Phosphate-Dependent Organism”. 《Science》 337 (6093): 467–70. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..467E. doi:10.1126/science.1218455. PMID 22773139.

- ↑ Reaves, M. L.; Sinha, S.; Rabinowitz, J. D.; Kruglyak, L.; Redfield, R. J. (2012). “Absence of Detectable Arsenate in DNA from Arsenate-Grown GFAJ-1 Cells”. 《Science》 337 (6093): 470–3. arXiv:1201.6643. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..470R. doi:10.1126/science.1219861. PMC 3845625. PMID 22773140.

- ↑ Anke M. (1986) "Arsenic", pp. 347–372 in Mertz W. (ed.), Trace elements in human and Animal Nutrition, 5th ed. Orlando, FL: Academic Press

- ↑ Uthus E.O. “Evidency for arsenical essentiality”. doi:10.1007/BF01783629. PMID 24197927.

- ↑ Uthus E.O. (1994) "Arsenic essentiality and factors affecting its importance", pp. 199–208 in Chappell W.R, Abernathy C.O, Cothern C.R. (eds.) Arsenic Exposure and Health. Northwood, UK: Science and Technology Letters.

- ↑ Baccarelli, A.; Bollati, V. (2009). “Epigenetics and environmental chemicals”. 《Current Opinion in Pediatrics》 21 (2): 243–251. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832925cc. PMC 3035853. PMID 19663042.

- ↑ Nicholis, I.; Curis, E.; Deschamps, P.; Bénazeth, S. (2009). “Arsenite medicinal use, metabolism, pharmacokinetics and monitoring in human hair”. 《Biochimie》 91 (10): 1260–7. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2009.06.003. PMID 19527769.

- ↑ Lombi, E.; Zhao, F. -J.; Fuhrmann, M.; Ma, L. Q.; McGrath, S. P. (2002). “Arsenic Distribution and Speciation in the Fronds of the Hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata”. 《New Phytologist》 156 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00512.x. JSTOR 1514012.

- ↑ Sakurai, Teruaki Sakurai (2003). “Biomethylation of Arsenic is Essentially Detoxicating Event”. 《Journal of Health Science》 49 (3): 171–178. doi:10.1248/jhs.49.171.

- ↑ Reimer, K.J.; Koch, I.; Cullen, W.R. (2010). “Organoarsenicals. Distribution and transformation in the environment”. 《Metal ions in life sciences》 7: 165–229. doi:10.1039/9781849730822-00165. ISBN 978-1-84755-177-1. PMID 20877808.

- ↑ Bentley, Ronald; Chasteen, TG (2002). “Microbial Methylation of Metalloids: Arsenic, Antimony, and Bismuth”. 《Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews》 66 (2): 250–271. doi:10.1128/MMBR.66.2.250-271.2002. PMC 120786. PMID 12040126.

- ↑ Cullen, William R; Reimer, Kenneth J. (1989). “Arsenic speciation in the environment”. 《Chemical Reviews》 89 (4): 713–764. doi:10.1021/cr00094a002.

- ↑ “Case Studies in Environmental Medicine (CSEM) Arsenic Toxicity Exposure Pathways” (PDF). Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. 2010년 5월 15일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Arsenic in Food: FAQ”. 2011년 12월 5일. 2010년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Arsenic. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (2009).

- ↑ Meharg, Andrew (2005). 《Venomous Earth – How Arsenic Caused The World's Worst Mass Poisoning》. Macmillan Science. ISBN 978-1-4039-4499-3.

- ↑ Henke, Kevin R (2009년 4월 28일). 《Arsenic: Environmental Chemistry, Health Threats and Waste Treatment》. 317쪽. ISBN 978-0-470-02758-5.

- ↑ Lamm, S. H.; Engel, A.; Penn, C. A.; Chen, R.; Feinleib, M. (2006). “Arsenic cancer risk confounder in southwest Taiwan data set”. 《Environ. Health Perspect.》 114 (7): 1077–82. doi:10.1289/ehp.8704. PMC 1513326. PMID 16835062.

- ↑ Kohnhorst, Andrew (2005). “Arsenic in Groundwater in Selected Countries in South and Southeast Asia: A Review”. 《J Trop Med Parasitol》 28: 73.

- ↑ “Arsenic in Drinking Water: 3. Occurrence in U.S. Waters” (PDF). 2010년 5월 15일에 확인함.

- ↑ Welch, Alan H.; Westjohn, D.B.; Helsel, Dennis R.; Wanty, Richard B. (2000). “Arsenic in Ground Water of the United States: Occurrence and Geochemistry”. 《Ground Water》 38 (4): 589–604. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.2000.tb00251.x.

- ↑ Knobeloch, L. M.; Zierold, K. M.; Anderson, H. A. (2006). “Association of arsenic-contaminated drinking-water with prevalence of skin cancer in Wisconsin's Fox River Valley”. 《J. Health Popul Nutr》 24 (2): 206–13. PMID 17195561.

- ↑ “In Small Doses:Arsenic”. 《The Dartmouth Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program. Dartmouth College》.

- ↑ Courtney, D; Ely, Kenneth H.; Enelow, Richard I.; Hamilton, Joshua W. (2009). “Low Dose Arsenic Compromises the Immune Response to Influenza A Infection in vivo”. 《Environmental Health Perspectives》 117 (9): 1441–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.0900911. PMC 2737023. PMID 19750111.

- ↑ Klassen, R.A.; Douma, S.L.; Ford, A.; Rencz, A.; Grunsky, E. (2009). “Geoscience modeling of relative variation in natural arsenic hazard in potential in New Brunswick” (PDF). Geological Survey of Canada. 2013년 5월 2일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 10월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ferreccio, C.; Sancha, A. M. (2006). “Arsenic exposure and its impact on health in Chile”. 《J Health Popul Nutr》 24 (2): 164–75. PMID 17195557.

- ↑ Chu, H. A.; Crawford-Brown, D. J. (2006). “Inorganic arsenic in drinking water and bladder cancer: a meta-analysis for dose-response assessment”. 《Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health》 3 (4): 316–22. doi:10.3390/ijerph2006030039. PMID 17159272.

- ↑ “Arsenic in drinking water seen as threat – USATODAY.com”. 《USA Today》. 2007년 8월 30일. 2008년 1월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gulledge, John H.; O'Connor, John T. (1973). “Removal of Arsenic (V) from Water by Adsorption on Aluminum and Ferric Hydroxides”. 《J. American Water Works Assn.》 65 (8): 548–552.

- ↑ O'Connor, J. T.; O'Connor, T. L. “Arsenic in Drinking Water: 4. Removal Methods” (PDF).

- ↑ “In situ arsenic treatment”. 《insituarsenic.org》. 2010년 5월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Radloff, K. A.; Zheng, Y.; Michael, H. A.; Stute, M.; Bostick, B. C.; Mihajlov, I.; Bounds, M.; Huq, M. R.; Choudhury, I.; Rahman, M.; Schlosser, P.; Ahmed, K.; Van Geen, A. (2011). “Arsenic migration to deep groundwater in Bangladesh influenced by adsorption and water demand”. 《Nature Geoscience》 4 (11): 793–798. Bibcode:2011NatGe...4..793R. doi:10.1038/ngeo1283. PMC 3269239. PMID 22308168.

- ↑ Yavuz, Cafer T; Mayo, J. T.; Yu, W. W.; Prakash, A.; Falkner, J. C.; Yean, S.; Cong, L.; Shipley, H. J.; Kan, A.; Tomson, M.; Natelson, D.; Colvin, V. L. (2005). “Low-Field Magnetic Separation of Monodisperse Fe3O4 Nanocrystals”. 《Science》 314 (5801): 964–967. doi:10.1126/science.1131475. PMID 17095696.

- ↑ Meliker, JR; Wahl, RL; Cameron, LL; Nriagu, JO (2007). “Arsenic in drinking water and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and kidney disease in Michigan: A standardized mortality ratio analysis”. 《Environmental Health》 6: 4. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-6-4. PMC 1797014. PMID 17274811.

- ↑ Tseng, Chin-Hsiao; Tai, Tong-Yuan; Chong, Choon-Khim; Tseng, Ching-Ping; Lai, Mei-Shu; Lin, Boniface J.; Chiou, Hung-Yi; Hsueh, Yu-Mei; Hsu, Kuang-Hung; Chen, CJ (2000). “Long-Term Arsenic Exposure and Incidence of Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus: A Cohort Study in Arseniasis-Hyperendemic Villages in Taiwan”. 《Environmental Health Perspectives》 108 (9): 847–51. doi:10.1289/ehp.00108847. PMC 2556925. PMID 11017889.

- ↑ Newspaper article (in Hungarian) published by Magyar Nemzet on 15 April 2012.

- ↑ Goering, P.; Aposhian, HV; Mass, MJ; Cebrián, M; Beck, BD; Waalkes, MP (1999). “The enigma of arsenic carcinogenesis: Role of metabolism”. 《Toxicological Sciences》 49 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1093/toxsci/49.1.5. PMID 10367337.

- ↑ Hopenhayn-Rich, C; Biggs, ML; Smith, AH; Kalman, DA; Moore, LE (1996). “Methylation study of a population environmentally exposed to arsenic in drinking water”. 《Environmental Health Perspectives》 104 (6): 620–628. doi:10.1289/ehp.96104620. PMC 1469390. PMID 8793350.

- ↑ Smith, AH; Arroyo, AP; Mazumder, DN; Kosnett, MJ; Hernandez, AL; Beeris, M; Smith, MM; Moore, LE (2000). “Arsenic-induced skin lesions among Atacameño people in Northern Chile despite good nutrition and centuries of exposure” (PDF). 《Environmental Health Perspectives》 108 (7): 617–620. doi:10.1289/ehp.00108617. PMC 1638201. PMID 10903614.

- ↑ Smedley, P. L. (2002). “A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters”. 《Applied Geochemistry》 17 (5): 517–568. doi:10.1016/S0883-2927(02)00018-5.

- ↑ How Does Arsenic Get into the Groundwater. Civil and Environmental Engineering. University of Maine

- ↑ Zeng Zhaohua, Zhang Zhiliang (2002). "The formation of As element in groundwater and the controlling factor". Shanghai Geology 87 (3): 11–15.

- ↑ “Redox control of arsenic mobilization in Bangladesh groundwater”. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2003.09.007.

- ↑ Thomas, Mary Ann (2007). "The Association of Arsenic With Redox Conditions, Depth, and Ground-Water Age in the Glacial Aquifer System of the Northern United States". U.S. Geological Survey, Virginia. pp. 1–18.

- ↑ Bin, Hong (2006). “Influence of microbes on biogeochemistry of arsenic mechanism of arsenic mobilization in groundwater”. 《Advances in earth science》 21 (1): 77–82.

- ↑ “The oxidation of arsenite in seawater”. doi:10.1080/00139307509437429.

- ↑ Cherry, J. A. “Arsenic species as an indicator of redox conditions in groundwater”. doi:10.1016/S0167-5648(09)70027-9.

- ↑ “Arsenic speciation in the environment”. doi:10.1021/cr00094a002.

- ↑ Oremland, Ronald S. “Bacterial dissimilatory reduction of arsenate and sulfate in meromictic Mono Lake, California”. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00422-1.

- ↑ Reese, Jr., Robert G. “Commodity Summaries 2002: Arsenic” (PDF). United States Geological Survey. 2008년 12월 17일에 보존된 문서 (PDF). 2008년 11월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Chromated Copper Arsenate (CCA)”. US Environmental Protection Agency.

- ↑ Townsend, Timothy G.; Solo-Gabriele, Helena (2006년 6월 2일). 《Environmental Impacts of Treated Wood》. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420006216.

- ↑ Saxe, Jennifer K.; Wannamaker, Eric J.; Conklin, Scott W.; Shupe, Todd F.; Beck, Barbara D. (2007년 1월 1일). “Evaluating landfill disposal of chromated copper arsenate (CCA) treated wood and potential effects on groundwater: evidence from Florida”. 《Chemosphere》 66 (3): 496–504. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.063. ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 16870233.

- ↑ BuildingOnline. “CCA Treated Wood Disposal | Wood Preservative Science Council | Objective, Sound, Scientific Analysis of CCA”. 《www.woodpreservativescience.org》. 2016년 6월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ “TRI Releases Map”. Toxmap.nlm.nih.gov. 2010년 3월 20일에 보존된 문서. 2010년 3월 23일에 확인함.

- ↑ TOXNET – Databases on toxicology, hazardous chemicals, environmental health, and toxic releases. Toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Jain, CK; Singh, RD (2012). “Technological options for the removal of arsenic with special reference to South East Asia”. 《Journal of Environmental Management》 107: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.04.016. PMID 22579769.

- ↑ Goering, P. (2013). “Bioremediation of arsenic-contaminated water: recent advances and future prospects”. 《Water, Air, & Soil Pollution》 224: 1722. doi:10.1007/s11270-013-1722-y.

- ↑ Goering, P. (2015). “Anaerobic arsenite oxidation with an electrode serving as the sole electron acceptor: A novel approach to the bioremediation of arsenic-polluted groundwater.”. 《Journal of Hazardous Materials》 283: 617–622. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.10.014.

- ↑ Arsenic Rule. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Adopted 22 January 2001; effective 23 January 2006.

- ↑ 가 나 다 “Supporting Document for Action Level for Arsenic in Apple Juice”. Fda.gov. 2013년 8월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Lawmakers Urge FDA to Act on Arsenic Standards. Foodsafetynews.com (2012-02-24). Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ “A Homeowner's Guide to Arsenic in Drinking Water”. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. 2013년 8월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. “#0038”. 미국 국립 직업안전위생연구소 (NIOSH).

- ↑ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. “#0039”. 미국 국립 직업안전위생연구소 (NIOSH).

- ↑ Total Diet Study and Toxic Elements Program

- ↑ Kotz, Deborah (2011년 9월 14일). “Does apple juice have unsafe levels of arsenic? – The Boston Globe”. Boston.com. 2013년 8월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ Morran, Chris. “Consumer Reports Study Finds High Levels Of Arsenic & Lead In Some Fruit Juice”. consumerist.com.

- ↑ “Arsenic contamination of Bangladeshi paddy field soils: implications for rice contribution to arsenic consumption : Nature News”. Nature.com. 2002년 11월 22일. 2013년 8월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Tainted wells pour arsenic onto food crops”. New Scientist. 2002년 12월 6일. 2013년 8월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ Peplow, Mark (2005년 8월 2일). “US rice may carry an arsenic burden”. 《Nature News》. doi:10.1038/news050801-5.