플라보노이드

플라보노이드(영어: flavonoid) 또는 바이오플라보노이드(영어: bioflavonoid) ("노랗다"라는 뜻의 라틴어 flavus에서 유래함)는 식물이나 균류의 이차대사산물의 일종이다.

화학적으로 플라보노이드는 두 개의 페닐 고리(A와 B)와 헤테로 사이클릭 고리(C)로 구성된 15개의 탄소 골격의 일반적인 구조를 가지고 있다. 이 탄소 구조는 C6-C3-C6으로 축약될 수있으며 이러한 골격을 갖는 식물 색소를 통틀어 플라보노이드라 한다. IUPAC 명명법에 따르면, 다음과 같이 분류 될 수 있다.[1][2]

- 플라보노이드 또는 바이오플라보노이드

- 3-페닐 크로몬(3-페닐-1,4-벤조 피론) 구조로부터 유도된 이소플라보노이드

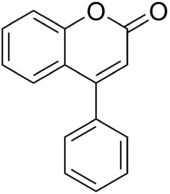

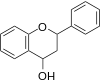

- 4-페닐 쿠마린(4-페닐-1,2-벤조 피론) 구조로부터 유도된 네오플라보노이드

위의 세 가지 플라보노이드는 모두 케톤 함유 화합물이며, 따라서 안토잔틴(플라본 및 플라보놀)이다. 이 화합물들이 최초로 바이오플라보노이드라고 불렸다. 플라보노이드 및 바이오플라보노이드라는 용어는, 정확하게는 플라바노이드(flavanoid)라고 불리는 비-케톤 폴리 하이드록시 폴리페놀 화합물을 가리키는 위해서도 사용되었다. 플라보노이드 백본의 3개의 사이클 또는 헤테로사이클은 일반적으로 고리 A, B, C로 불린다. 고리 A는 일반적으로 플로로글루시놀(phloroglucinol) 치환 패턴을 나타낸다.

종류[편집]

5000 가지가 넘는 천연 플라보노이드가 다양한 식물로부터 확인되었다. 그 화합물들은 화학 구조에 따라 분류되었으며 대개 다음 하위 그룹으로 나뉜다.(참고 자료:[3])

안토잔틴[편집]

| 군 | 기본골격 | 예시 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 설명 | 작용기 | 구조식 | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

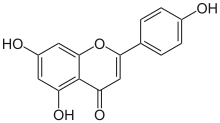

| 플라본 Flavone |

2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✗ | ✗ |

|

en:Luteolin, en:Apigenin, en:Tangeritin |

| 플라보놀 Flavonol 또는 3-hydroxyflavone |

3-hydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✓ | ✗ |

|

en:Quercetin, en:Kaempferol, en:Myricetin, en:Fisetin, en:Galangin, en:Isorhamnetin, en:Pachypodol, en:Rhamnazin, en:Pyranoflavonols, en:Furanoflavonols, |

플라바논[편집]

| 군 | 기본골격 | 예시 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 설명 | 작용기 | 구조식 | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

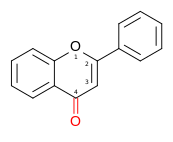

| 플라바논 Flavanone |

2,3-dihydro-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✗ | ✓ |

|

en:Hesperetin, en:Naringenin, en:Eriodictyol, en:Homoeriodictyol |

플라바논올[편집]

| 군 | 기본골격 | 예시 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 설명 | 작용기 | 구조식 | |||

| 3-hydroxyl | 2,3-dihydro | ||||

| 플라바노놀 Flavanonol 또는 3-Hydroxyflavanone 또는 2,3-dihydroflavonol |

3-hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-2-phenylchromen-4-one | ✓ | ✓ |

|

en:Taxifolin (또는 en:Dihydroquercetin), en:Dihydrokaempferol |

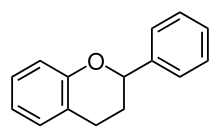

플라반[편집]

| 기본골격 | 이름 |

|---|---|

|

en:Flavan-3-ol (flavanol) |

|

en:Flavan-4-ol |

|

en:Flavan-3,4-diol (leucoanthocyanidin) |

- Flavan-3-ols (플라바놀)

- Flavan-3-ols은 2-페닐-3,4-디하이드로-2H-크로멘-3-올 골격을 사용한다.

- 예시: 카테킨 (C), en:Gallocatechin (GC), en:Catechin 3-gallate (Cg), en:Gallocatechin 3-gallate (GCg), 에피카테킨(카테킨 (EC)), en:Epigallocatechin (EGC), en:Epicatechin 3-gallate (ECg), 에피갈로카테킨 갈레이트 (EGCg)

- en:Thearubigin

- 프로안토시아니딘(proanthocyanidin)은 플라바놀의 중합체 또는 이합체, 삼합체, 올리고머의 형태이다

안토시아니딘 (Anthocyanidin)[편집]

- 안토시아니딘은 안토시아닌의 아글리콘(aglycone)이다. 기본 골격은 플라빌륨(2-페닐크로메닐륨) 이온이다.

- 예시: en:Cyanidin, en:Delphinidin, en:Malvidin, en:Pelargonidin, en:Peonidin, en:Petunidin

아이소플라본[편집]

공급원이 되는 식품[편집]

플라보노이드 (특히 카테킨, 플라바놀과 같은 플라노보이드는 "인간의 식이에서 가장 흔한 폴리페놀 화합물이며, 거의 모든 식물에 포함되어 있다.") [5] 쿼세틴과 같은 바이오플라보노이드는 플라보놀이라고도 불리며, 이 역시 많은 식물에 포함되어 있으나 양은 비교적 적다.

다른 활성 식물 화합물(예를 들면 알칼로이드)에 비해 플라보노이드는, 그 다양성 및 상대적으로 낮은 독성, 광범위한 분포는 사람을 포함한 많은 동물의 식이에 상당한 비중을 차지한다는 것을 의미한다.

플라보노이드 함량이 높은 식품은 파슬리 [6], 양파[6], 블루베리 및 딸기류, 홍차[6], 녹차 및 우롱차[6], 바나나, 모든 감귤류, 은행, 적포도주, 바다 갈매나무, 다크 초콜릿(코코아 함량 70 % 이상)등이 있다.

플라보노이드의 식이 공급원에 대한 자세한 내용은 미국 농무부 플라보노이드 데이터베이스에서 얻을 수 있다. [6]

파슬리[편집]

파슬리, 날 것과 말린 것 모두 플라본을 포함한다.[6]

블루베리[편집]

홍차[편집]

감귤류[편집]

감귤류의 플라보노이드에는 헤스페리딘(flavanone hesperetin의 배당체), 쿼시트린, 플라보놀 쿼세틴의 두 가지 배당체인 루틴(rutin) 및 플라본 탠저리틴이 포함된다.

코코아[편집]

플라보노이드는 코코아에 자연적으로 존재하지만 쓴 맛이 있기 때문에 초콜렛, 심지어는 다크 초콜릿에서도 종종 제거된다. [8] 밀크 초콜릿에도 플라보노이드가 함유되어 있지만 우유는 흡수를 방해 할 수 있다고 한다. [9][10] 그러나 이 결론에는 의문이 제기되었다.[11]

땅콩[편집]

땅콩의 빨간 껍질에는 플라보노이드를 포함한 중요한 폴리 페놀 성분이 포함되어 있다. [12] [13]

| 식품 | 플라본 | 플라보놀 | 플라바논 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 적 양파 | 0 | 4 - 100 | 0 |

| 파슬리, 날 것 | 24 - 634 | 8 - 10 | 0 |

| 백리향, 날 것 | 56 | 0 | 0 |

| 레몬 주스, 날 것 | 0 | 0 - 2 | 2 - 175 |

연구[편집]

개별 플라보노이드의 건강에 대한 잠재적인 긍정적 효과에 대해, 진행중인 연구가 있지만, 미국 식품의약국(FDA)이나 유럽 식품 안전청(EFSA)은 플라보노이드에 대한 건강 유익 표시를 승인하지 않았고 플라보노이드를 의약품으로 승인하지도 않았다.[15][16][17]

게다가 몇몇 회사는 오해의 소지가 있는 건강 유익 표시에 대해 FDA로부터 주의를 받았다.[18][19][20][21]

인 비트로[편집]

플라보노이드는 인 비트로 연구에서 광범위한 생물학적 및 약리학적 활성을 갖는 것으로 나타났다. 예를 들면, 항알레르기,[22] 항염증,[22][23] 항산화 물질,[23] 항미생물(항균,[24][25] 항진균,[26][27] 항바이러스[26][27]), 암,[23][28] 설사 방지 활성 등이 있다.[29]

플라보노이드는 또한 DNA 회전효소를 억제하고[30][31] 인 비트로 연구에서 mixed-lineage leukemia(MLL) 유전자에서 DNA 돌연변이를 유도하는 것으로 나타났다.[32]

그러나 위의 사례의 대부분에서 인 비보 또는 후속 임상시험이 수행되지 않아 이러한 활동이 인체 건강에 유익하거나 해로운 영향을 미치는지 여부를 말할 수 없다. 더 깊이 조사 된 생물학적 및 약리학 적 활동은 아래에서 설명한다.

항산화[편집]

라이너스 폴링 연구소(Linus Pauling Institute)와 유럽 식품 안전청(EFSA)의 연구에 따르면 플라보노이드는 인체에 흡수되기 어렵고(5% 미만), 흡수되는 물질의 대부분은 신속하게 대사되고 배설된다.[17][33][34]

이러한 결과는 플라보노이드가 가진 항산화 활성은 무시할 만한 수준이며, 플라보노이드가 풍부한 식품을 섭취한 후에 나타나는 혈액의 항산화 능력이 플라보노이드에 직접적으로 기인한 것이 아니라, 플라보노이드의 분해와 배설 활동으로 인한 요산의 생산 때문이다.[35]

같이 보기[편집]

각주[편집]

- ↑ McNaught, Alan D; Wilkinson, Andrew; IUPAC (1997), 〈IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology〉, 《IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology》 2판, Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, doi:10.1351/goldbook.F02424, ISBN 0-9678550-9-8

- ↑ “The Gold Book”. 2009. doi:10.1351/goldbook. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. 2012년 9월 16일에 확인함.

|장=이 무시됨 (도움말) - ↑ Ververidis F, Trantas E, Douglas C, Vollmer G, Kretzschmar G, Panopoulos N (October 2007). “Biotechnology of flavonoids and other phenylpropanoid-derived natural products. Part I: Chemical diversity, impacts on plant biology and human health”. 《Biotechnology Journal》 2 (10): 1214–34. doi:10.1002/biot.200700084. PMID 17935117.

- ↑ Isolation of a UDP-glucose: Flavonoid 5-O-glucosyltransferase gene and expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.). Da Qiu Zhao, Chen Xia Han, Jin Tao Ge and Jun Tao, Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 15 November 2012, Volume 15, Number 6, doi 10.2225/vol15-issue6-fulltext-7

- ↑ Spencer JP (2008). “Flavonoids: modulators of brain function?”. 《British Journal of Nutrition》 99: ES60–77. doi:10.1017/S0007114508965776. PMID 18503736.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 아 USDA’s Database on the Flavonoid Content

- ↑ Ayoub M, de Camargo AC, Shahidi F (2016). “Antioxidants and bioactivities of free, esterified and insoluble-bound phenolics from berry seed meals”. 《Food Chemistry》 197 (Part A): 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.107.

- ↑ “The devil in the dark chocolate”. 《Lancet》 370 (9605): 2070. 2007. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61873-X. PMID 18156011.

- ↑ Serafini M, Bugianesi R, Maiani G, Valtuena S, De Santis S, Crozier A (2003). “Plasma antioxidants from chocolate”. 《Nature》 424 (6952): 1013. Bibcode:2003Natur.424.1013S. doi:10.1038/4241013a. PMID 12944955.

- ↑ Serafini M, Bugianesi R, Maiani G, Valtuena S, De Santis S, Crozier A (2003). “Nutrition: milk and absorption of dietary flavanols”. 《Nature》 424 (6952): 1013. Bibcode:2003Natur.424.1013S. doi:10.1038/4241013a. PMID 12944955.

- ↑ Roura E, 외. (2007). “Milk Does Not Affect the Bioavailability of Cocoa Powder Flavonoid in Healthy Human” (PDF). 《Ann Nutr Metab》 51: 493–498. doi:10.1159/000111473.[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)]

- ↑ de Camargo AC, Regitano-d'Arce MA, Gallo CR, Shahidi F (2015). “Gamma-irradiation induced changes in microbiological status, phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of peanut skin”. 《Journal of Functional Foods》 12: 129–143. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2014.10.034.

- ↑ Chukwumah Y, Walker LT, Verghese M (2009). “Peanut skin color: a biomarker for total polyphenolic content and antioxidative capacities of peanut cultivars”. 《Int J Mol Sci》 10 (11): 4941–52. doi:10.3390/ijms10114941. PMC 2808014. PMID 20087468.

- ↑ “Flavonoids - Linus Pauling Institute - Oregon State University”. 2016년 2월 26일에 확인함.

- ↑ “FDA approved drug products”. US Food and Drug Administration. 2013년 11월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Health Claims Meeting Significant Scientific Agreement”. US Food and Drug Administration. 2013년 11월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA)2, 3 European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Parma, Italy (2010). “Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061” (PDF). 《EFSA Journal》 8 (2): 1489. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1489.

- ↑ “Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations (Flavonoid Sciences)”. US Food and Drug Administration. 2013년 11월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations (Unilever, Inc.)”. US Food and Drug Administration. 2013년 10월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Lipton green tea is a drug”. NutraIngredients-USA.com. 2013년 10월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Fruits Are Good for Your Health? Not So Fast: FDA Stops Companies From Making Health Claims About Foods”. TheDailyGreen.com. 2013년 12월 3일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 10월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB (2001). “Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer”. 《Journal of Clinical Investigation》 107 (2): 135–42. doi:10.1172/JCI11914. PMC 199180. PMID 11160126.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Cazarolli LH, Zanatta L, Alberton EH, Figueiredo MS, Folador P, Damazio RG, Pizzolatti MG, Silva FR (2008). “Flavonoids: Prospective Drug Candidates”. 《Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry》 8 (13): 1429–1440. doi:10.2174/138955708786369564. PMID 18991758.

- ↑ Cushnie TP, Lamb AJ (2011). “Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids”. 《International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents》 38 (2): 99–107. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.014. PMID 21514796.

- ↑ Manner S, Skogman M, Goeres D, Vuorela P, Fallarero A (2013). “Systematic exploration of natural and synthetic flavonoids for the inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms”. 《International Journal of Molecular Sciences》 14 (10): 19434–19451. doi:10.3390/ijms141019434. PMC 3821565. PMID 24071942.

- ↑ 가 나 Cushnie TP, Lamb AJ (2005). “Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids” (PDF). 《International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents》 26 (5): 343–356. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. PMID 16323269. 2013년 10월 8일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 4월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Friedman M (2007). “Overview of antibacterial, antitoxin, antiviral, and antifungal activities of tea flavonoids and teas”. 《Molecular Nutrition and Food Research》 51 (1): 116–134. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200600173. PMID 17195249.

- ↑ de Sousa RR, Queiroz KC, Souza AC, Gurgueira SA, Augusto AC, Miranda MA, Peppelenbosch MP, Ferreira CV, Aoyama H (2007). “Phosphoprotein levels, MAPK activities and NFkappaB expression are affected by fisetin”. 《J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem》 22 (4): 439–444. doi:10.1080/14756360601162063. PMID 17847710.

- ↑ Schuier M, Sies H, Illek B, Fischer H (2005). “Cocoa-related flavonoids inhibit CFTR-mediated chloride transport across T84 human colon epithelia”. 《J. Nutr.》 135 (10): 2320–5. PMID 16177189.

- ↑ Esselen M, Fritz J, Hutter M, Marko D (2009). “Delphinidin Modulates the DNA-Damaging Properties of Topoisomerase II Poisons”. 《Chemical Research in Toxicology》 22 (3): 554–64. doi:10.1021/tx800293v. PMID 19182879.

- ↑ Bandele OJ, Clawson SJ, Osheroff N (2008). “Dietary polyphenols as topoisomerase II poisons: B-ring substituents determine the mechanism of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage enhancement”. 《en:Chemical Research in Toxicology》 21 (6): 1253–1260. doi:10.1021/tx8000785. PMC 2737509. PMID 18461976.

- ↑ Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani S, Janssen J, Maas LM, Godschalk RW, Nijhuis JG, van Schooten FJ (2007). “Dietary flavonoids induce MLL translocations in primary human CD34+ cells”. 《Carcinogenesis》 28 (8): 1703–9. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgm102. PMID 17468513.

- ↑ Lotito SB, Frei B (2006). “Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon?”. 《Free Radic. Biol. Med.》 41 (12): 1727–46. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033. PMID 17157175.

- ↑ Williams RJ, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C (2004). “Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules?”. 《Free Radical Biology & Medicine》 36 (7): 838–49. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. PMID 15019969.

- ↑ Stauth D (2007년 3월 5일). “Studies force new view on biology of flavonoids”. EurekAlert!, Adapted from a news release issued by Oregon State University.