콜리스틴

| |

| |

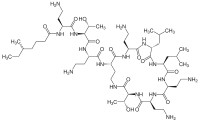

| 체계적 명칭 (IUPAC 명명법) | |

|---|---|

| N-(4-amino-1-(1-(4-amino-1-oxo-1-(3,12,23-tris(2-aminoethyl)- 20-(1-hydroxyethyl)-6,9-diisobutyl-2,5,8,11,14,19,22-heptaoxo- 1,4,7,10,13,18-hexaazacyclotricosan-15-ylamino)butan-2-ylamino)- 3-hydroxybutan-2-ylamino)-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-N,5-dimethylheptanamide | |

| 식별 정보 | |

| CAS 등록번호 | 1066-17-7 |

| ATC 코드 | A07AA10 J01XB01, QA07AA10, QA07AA98, QG51AG07, QJ01XB01, QJ51XB01 |

| PubChem | 5311054 |

| 드러그뱅크 | DB00803 |

| ChemSpider | 4470591 |

| 화학적 성질 | |

| 화학식 | C52H98N16O13 |

| 분자량 | ? |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| 약동학 정보 | |

| 생체적합성 | 0% |

| 동등생물의약품 | ? |

| 약물 대사 | ? |

| 생물학적 반감기 | 5 hours |

| 배출 | ? |

| 처방 주의사항 | |

| 허가 정보 | |

| 임부투여안전성 | C(미국) |

| 법적 상태 | |

| 투여 방법 | Topical, by mouth, intravenous, intramuscular, inhalation |

콜리스틴(colistin)은 폴리믹신 E (polymyxin E)로도 알려져 있으며, 폐렴을 포함한 다제 내성 그람 음성 감염에 대한 최후의 치료법으로 사용되는 항생제이다.[7][8] 여기에는 녹농균(Pseudomonas aeruginosa), 폐렴간균(Klebsiella pneumoniae) 또는 아시네토박터(Acinetobacter)와 같은 박테리아가 포함될 수 있다.[9] 콜리스티메테이트나트륨(colistimethate sodium)은 정맥 주사, 근육 주사, 흡입의 두 가지 형태가 있으며, 황산콜리스틴(colistin sulfate)은 주로 피부에 바르거나 경구 복용한다.[10] 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨[11] 전구약물(prodrug)으로서, 이는 콜리스틴과 포름알데히드 및 중아황산나트륨의 반응에 의해 생성되며, 이로 인해 콜리스틴의 1차 아민에 설포메틸 그룹이 추가된다. 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨은 비경구 투여 시 콜리스틴보다 독성이 적다. 수용액에서는 가수분해되어 부분적으로 설포메틸화된 유도체와 콜리스틴의 복잡한 혼합물을 형성한다. 콜리스틴에 대한 내성은 2015년부터 나타나기 시작했다[12]

콜리스틴 주사제의 일반적인 부작용으로는 신장 문제와 신경학적 문제가 있다.[8] 다른 심각한 부작용으로는 아나필락시스, 근육 약화, 디피실리균(Clostridium difficile) 관련 설사 등이 있다.[8] 흡입된 형태는 세기관지를 수축 시킬 수 있다.[8] 임신 중 사용이 태아에게 안전한지는 불분명하다.[13] 콜리스틴은 폴리믹신(polymyxin) 계열 약물에 속한다.[8] 이는 일반적으로 세균 세포 사멸을 초래하는 세포막을 파괴함으로써 작동한다.[8]

콜리스틴은 1947년에 발견되었고 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨은 1970년 미국에서 의료용으로 승인되었다.[9][8] 이는 세계보건기구(WHO)의 필수 의약품 목록에 포함되어 있다.[14] 세계보건기구(WHO)는 콜리스틴을 인체 의학에 매우 중요한 물질로 분류한다.[15] 일반 의약품으로 이용 가능하다.[16] 이 항생물질은 패니바실러스(Paenibacillus) 속의 박테리아에서 유래되었다.[10]

- Brucella

- Burkholderia cepacia

- Chryseobacterium indologenes

- Edwardsiella

- Elizabethkingia meningoseptica

- Francisella tularensis spp.

- Gram-negative cocci

- Helicobacter pylori

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- Morganella spp.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis

- Proteus

- Providencia

- Serratia

- 몇몇 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

의료용[편집]

항균 스펙트럼[편집]

콜리스틴은 녹농균(Pseudomonas), 대장균(Escherichia) 및 크렙시엘라(Klebsiella) 종에 의한 감염을 치료하는 데 효과적이었다. 다음은 의학적으로 중요한 몇 가지 미생물에 대한 최소 억제 농도(MIC) 민감성 데이터이다.[17][18]

- 대장균(Escherichia coli) : 0.12~128μg/mL

- 크렙시엘라균(Klebsiella pneumoniae) : 0.25~128μg/mL

- 녹농균(Pseudomonas aeruginosa) : ≤0.06~16μg/mL

예를 들어, 콜리스틴은 다른 약물과 결합하여 낭포성 섬유증 환자의 폐에서 녹농균(P. aeruginosa) 생물막(biofilm) 감염을 공격한다.[19] 생물막은 박테리아가 대사적으로 활동하지 않는 표면 아래에 저산소 환경을 갖고 있으며 콜리스틴은 이 환경에서 매우 효과적이다. 그러나 녹농균(P. aeruginosa)은 생물막의 최상층에 존재하며 대사 활성 상태를 유지한다.[20] 이는 살아남은 관용 세포가 필리(pili)를 통해 생물막의 상단으로 이동하고 쿼럼 감지(quorum sensing)를 통해 새로운 집합체를 형성하기 때문이다.[21]

투여 및 복용량[편집]

양식[편집]

콜리스틴은 두 가지 형태, 즉 콜리스틴 황산염과 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨(콜리스틴 메탄설포네이트 나트륨, 콜리스틴 설포메테이트 나트륨)의 두 가지가 이용 가능하다. 콜리스틴 황산염은 양이온성이다. 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨은 음이온성이다. 콜리스틴 황산염은 안정적인 반면, 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨은 다양한 메탄술폰화 유도체로 쉽게 가수분해된다. 콜리스틴 황산염과 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨은 다양한 경로를 통해 신체에서 제거된다. 녹농균(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)과 관련하여, 콜리스티메테이트는 콜리스틴의 불활성 전구약물이다. 두 약물은 서로 바꿔 사용할 수 없다.

- Colistimethate 나트륨은 낭포성 섬유증 환자의 녹농균(Pseudomonas aeruginosa) 감염을 치료하는 데 사용될 수 있으며, 내성 형태가 보고되었지만 최근 다제 내성 아시노박터(Acinetobacter) 감염 치료에 사용되었다.[22][23] Colistimethate 나트륨은 또한 아시노박터(Acinetobacter baumannii) 및 녹농균(Pseudomonas aeruginosa) 수막염 및 뇌실염에 척수강 내 및 뇌실 내로 투여되었다.[24][25][26][27] 일부 연구에서는 콜리스틴이 아시노박터(Acinetobacter)의 카바페넴 내성 분리균으로 인한 감염 치료에 유용할 수 있음을 나타냈다.[23]

- 콜리스틴 황산염은 장 감염을 치료하거나 결장 세균총을 억제하는 데 사용될 수 있다. 콜리스틴 황산염은 국소 크림, 분말 및 귀 용액에도 사용된다.

- 콜리스틴 A(폴리믹신 E1)와 콜리스틴 B(폴리믹신 E2)는 개별적으로 정제되어 별도의 화합물로서 효과와 효능을 연구하고 연구할 수 있다.

복용량[편집]

콜리스틴 황산염과 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨은 모두 정맥으로 투여할 수 있지만 투여 방법이 복잡하다. 한 연구에서는 세계 각지의 콜리스틴 메탄술폰산염의 비경구 제품에 대한 다양한 라벨링을 지적하기 했다.[28] Xellia 에서 제조한 Colistimethate 나트륨(Colomycin 주사제)은 국제 단위로 처방되는 반면 Parkdale에서 제조한 Colistimethate 나트륨(Coly-Mycin M Parenteral)은 콜리스틴 염기의 mg 단위로 처방된다.

- 콜로마이신 1,000,000 단위(unit)는 80 mg 콜리스티메테이트이다;[29]

- 콜리마이신 M 150 mg 콜리스틴 염기는 360 mg 콜리스티메테이트 또는 4,500,000 단위(unit)이다.[30]

콜리스틴은 50여년 전에 임상에 도입되었기 때문에 현대 의약품이 적용되는 규정을 따르지 않았으며, 따라서 콜리스틴의 표준화된 용량이 없고 약리학이나 약동학에 대한 자세한 시험도 없다. 따라서 대부분의 감염에 대한 최적의 콜리스틴 투여량은 알려져 있지 않다. 콜로마이신은 체중 60kg 혹은 이상의 정상 신장기능 환자의 경우 1일 3회 1~200만 단위의 정맥 투여가 권장된다. Coly-Mycin의 권장 복용량은 2.5~5 mg/kg이다. 이는 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨 6~12mg/kg에 해당된다. 60kg 남성의 경우, 그러므로 Colomycin의 권장 복용량은 240~480mg이다. 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨 mg이지만 Coly-Mycin의 권장 복용량은 360~720mg이다. 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨과 마찬가지로, 각 제제에 대해 권장되는 "최대" 용량도 다르다(콜로마이신 480mg 및 Coly-Mycin 720mg). 국가마다 콜리스틴의 일반 제제가 다르며 권장 복용량은 제조업체에 따라 다르다. 용량에 대한 규제나 표준화가 전혀 없기 때문에 의사가 콜리스틴 정맥 투여를 어렵게 만든다.

콜리스틴은 리팜피신과 함께 사용되었다. 시험관 내 시너지 효과에 대한 증거가 존재하며[31][32] 이 조합은 환자에게 성공적으로 사용되었다.[33] 다른 항-슈도모나스 항생제와 함께 사용되는 콜리스티메테이트 나트륨의 시너지 효과에 대한 시험관 내 증거도 있다.[34]

Colistimethate 나트륨 에어로졸(Promixin; Colomycin 주사제)은 특히 낭포성 섬유증에서 폐 감염을 치료하는 데 사용된다. 영국의 경우 성인 권장 복용량은 1~200만 단위(80~160단위)이다. mg) 분무된 콜리스트메테이트를 하루 2회.[35][29] 분무된 콜리스틴은 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환 및 녹농균 감염 환자의 심각한 악화를 감소시키는 데에도 사용되었다.[36]

내성[편집]

콜리스틴에 대한 내성은 드물지만 존재한다. 2017년 기준[update] 콜리스틴 저항성을 정의하는 방법에 대한 통일된 합의는 없다. 프랑스 미생물 학회는 MIC 컷오프 2mg/L를 사용한다. 반면, 영국항균화학요법학회에서는 MIC 컷오프를 4mg/L 이하는 감수성, 8mg/L이상은 저항성으로 설정했다. 미국에서는 콜리스틴 감수성을 설명하는 표준이 없다.

박테리아 균주 간에 전달될 수 있는 플라스미드에서 처음으로 알려진 콜리스틴 내성 유전자는 mcr-1이다. 이는 2011년 중국의 한 돼지농장에서 콜리스틴을 일상적[37] 사용하는 곳에서 발견돼 2015년 11월 대중에게 알려지게 됐다[38] 이 플라스미드 유래 유전자의 존재는 2015년 12월부터 동남아시아, 여러 유럽 국가,[39] 및 미국에서 확인되었다.[40] 이는 Paenibacillus polymyxa 박테리아의 특정 계통에서 발견된다.

인도에서는 18개월에 걸쳐 기록된 13건의 콜리스틴 내성 감염에 대한 상세한 콜리스틴 내성 연구를 최초로 발표했다. 범약물 내성 감염, 특히 혈류 감염의 사망률이 더 높다는 결론이 나왔다. 다른 인도 병원에서도 여러 사례가 보고되었다.[41][42] 폴리믹신에 대한 내성은 일반적으로 10% 미만이지만, 콜리스틴 내성률이 증가하는 지중해 및 동남아시아(한국, 싱가포르)에서 더 자주 발생한다.[43] 콜리스틴 내성 대장균은 2016년 5월 미국에서 확인되었다[44]

2016년부터 2021년까지의 최근 검토에서는 대장균이 mcr 유전자를 보유한 지배적인 종이라는 사실이 밝혀졌다. 플라스미드 매개 콜리스틴 저항성은 항생제에 저항하는 다양한 유전자를 보유하는 다른 종에도 부여된다.

Acinetobacter baumannii 감염을 치료하기 위해 콜리스틴을 사용하면 내성 박테리아 균주가 발생하게 된다. 그들은 또한 인간 면역 체계에서 생성되는 항균 화합물 LL-37 과 라이소자임에 대한 저항성을 발달시킨다. 이러한 교차 저항은 박테리아 염색체에 위치한 지질 A 포스포에탄올아민 전이효소 (mcr-1 과 유사)의 발현을 제어하는 pmrB 유전자에 대한 기능 획득 돌연변이로 인해 발생한다.[45] 유사한 결과가 mcr-1 양성 E. coli에서도 얻어졌는데, 이는 시험관 내 동물 항균 펩타이드 혼합물에서 더 잘 생존하고 감염된 애벌레를 죽이는 데 더 효과적이었다.[46]

콜리스틴과 일부 다른 항생제에 대한 모든 내성이 내성 유전자의 존재로 인한 것은 아니다.[47] 이종저항성(heteroresistance)은 분명히 유전적으로 동일한 미생물이 항생제에 대해 다양한 저항성을 나타내는 현상이다.[48] 적어도 2016년부터 일부 Enterobacter 종에서 관찰되었으며[47] 2017~2018년에는 Klebsiella pneumoniae 의 일부 계통에서 관찰되었다.[49] 어떤 경우에는 이 현상이 심각한 임상적 결과를 가져오기도 한다.[49]

콜리스틴 약물에 대한 본질적 저항력이 있는 세균[편집]

- Brucella

- Burkholderia cepacia

- Chryseobacterium indologenes

- Edwardsiella

- Elizabethkingia meningoseptica

- Francisella tularensis spp.

- Gram-negative cocci

- Helicobacter pylori

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- Morganella spp.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis

- Proteus

- Providencia

- Serratia

- 몇몇 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

가변 저항[편집]

부작용[편집]

정맥 주사에서 나타나는 주 독성은 신독성(신장 손상)과 신경 독성(신경 손상)이다.[50][51][52][53] 이는 신장 기능에 이상이 있는경우, 현재 제조사가 권장하는 복용량보다 높은 용량을 투여한 경우 발생할 수 있으며, 신경독성 및 신독성 효과는 일시적인 것으로 보이며 치료를 중단하거나 용량을 줄이면 사라진다.[54]

160mg의 복용량에서 콜리스티메테이트 IV를 8시간마다 투여하면 신독성이 거의 나타나지 않는다.[55][56] 실제로 콜리스틴은 이후에 이를 대체한 아미노글리코사이드보다 독성이 적은 것으로 보이며, 최대 6개월 동안 아무런 부작용 없이 장기간 사용되었다.[57] 콜리스틴 유발 신독성은 특히 저알부민혈증 환자에서 발생할 가능성이 높다.[58]

에어로졸 처치에서 발견되는 주요 독성은 경련[59][60]이다. 이는 살부타몰과 같은 β2-아드레날린 수용체 작용제를 사용하거나 탈감작 프로토콜에 따라 치료하거나 예방할 수 있다.[61]

작용 메커니즘[편집]

콜리스틴은 다가 양이온성 펩타이드이며 친수성 부분과 친유성 부분을 모두 가지고 있다.[62] 이러한 양이온 영역은 지질다당류의 마그네슘 및 칼슘 박테리아 반대 이온을 대체하여 박테리아 외막과 상호 작용한다. 소수성 친수성 영역은 마치 세제처럼 세포질막 과 상호작용하여 수용성 환경에서 막을 용해시킨다. 이 효과는 등삼투압 환경에서도 살균 효과가 있다.

콜리스틴은 그람 음성균의 세포막 외부에 있는 지질다당류와 인지질에 결합한다. 이는 막 지질의 인산염 그룹에서 2가 양이온(Ca 2+ 및 Mg 2+ )을 경쟁적으로 대체하여 외부 세포막을 파괴하고 세포 내 내용물의 누출 및 박테리아 사멸을 초래한다.

약동학[편집]

콜리스틴의 임상적으로 유용한 흡수는 위장관에서 발생하지 않는다. 따라서 전신 감염의 경우 콜리스틴을 주사로 투여해야 한다. 콜리스티메테이트는 신장에 의해 제거되지만, 콜리스틴은 아직 특성이 규명되지 않은 비신장 메커니즘에 의해 제거된다.[63][64]

역사[편집]

콜리스틴은 1949년 일본에서 고야마에 의해 바실러스 균(Bacillus polymyxa var. colistinus[65]) 발효 플라스크에서 처음 분리되었다. 1959년에 임상적으로 사용 가능해졌다.[66]

독성이 덜한 전구약물인 콜리스메테이트 나트륨은 1959년에 주사제로 사용 가능해졌다. 1980년대에 폴리믹신 사용은 신장 독성과 신경 독성 때문에 널리 중단되었다. 1990년대에 다제내성균이 더욱 널리 퍼지면서 콜리스틴은 독성에도 불구하고 긴급 해결책으로 다시 주목받기 시작했다.[67]

콜리스틴은 특히 1980년대부터 중국에서 농업에도 사용되었다. 2015년 중국의 농업 생산량은 2700톤을 초과했다. 중국은 2016년에 가축 성장 촉진을 위한 콜리스틴 사용을 금지했다[68]

생합성[편집]

콜리스틴의 생합성에는 트레오닌, 류신, 2,4-디아미노부트르산의 세 가지 아미노산이 필요하다다. 선형 형태의 콜리스틴은 고리화 전에 합성된다. 비리보솜 펩타이드 생합성은 로딩 모듈로 시작되고 이후 각 아미노산이 추가된다. 후속 아미노산은 아데닐화 도메인(A), 펩티딜 운반 단백질 도메인(PCP), 에피머화 도메인(E) 및 축합 도메인 (C)의 도움으로 추가된다. 티오에스테라제는 고리화를 시킨다.[69] 첫 번째 단계는 로딩 도메인인 6-메틸헵탄산을 A 및 PCP 도메인과 연관시키는 것이며, 2,4-디아미노부트리산과 연관된 C, A 및 PCP 도메인이 있어, 이는 선형 펩타이드 사슬이 완성될 때까지 각 아미노산에 대해 계속된다. 마지막 모듈에는 고리화를 완료하고 콜리스틴 생성물을 형성하는 티오에스테라제가 있다.

각주[편집]

- ↑ “Drug Product Database”. 《Health Canada》. 2012년 4월 25일. 2022년 1월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Colobreathe 1,662,500 IU inhalation powder, Hard Capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)”. 《(emc)》. 2020년 11월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Colomycin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for solution for injection, infusion or inhalation – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)”. 《(emc)》. 2020년 5월 27일. 2020년 11월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Promixin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for Nebuliser Solution – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)”. 《(emc)》. 2020년 9월 23일. 2020년 11월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Coly-Mycin M- colistimethate injection”. 《DailyMed》. 2018년 12월 3일. 2020년 11월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Colobreathe EPAR”. 《European Medicines Agency》. 2018년 9월 17일. 2020년 11월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Clinical considerations for optimal use of the polymyxins: A focus on agent selection and dosing”. 《Clinical Microbiology and Infection》 23 (4): 229–233. April 2017. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.023. PMID 28238870.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 “Colistimethate Sodium Monograph for Professionals”. 《Drugs.com》. 2019년 11월 6일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 “Potential of old-generation antibiotics to address current need for new antibiotics”. 《Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy》 6 (5): 593–600. October 2008. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.5.593. PMID 18847400.

- ↑ 가 나 《Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases E-Book》. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009. 469쪽. ISBN 9781437720600.

- ↑ “Colistin methanesulfonate is an inactive prodrug of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa”. 《Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy》 50 (6): 1953–1958. June 2006. doi:10.1128/AAC.00035-06. PMC 1479097. PMID 16723551.

- ↑ “Detection of mcr-1 encoding plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from human bloodstream infection and imported chicken meat, Denmark 2015”. 《Euro Surveillance》 20 (49): 30085. 2015년 12월 10일. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.49.30085. PMID 26676364.

- ↑ “Colistimethate (Coly Mycin M) Use During Pregnancy”. 《Drugs.com》. 2019년 11월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ 《World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019》. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ 《Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine》 6 revision판. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. ISBN 9789241515528.

- ↑ 《British national formulary : BNF 76》 76판. Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. 547쪽. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ “Polymyxin E (Colistin) – The Antimicrobial Index Knowledgebase – TOKU-E”. 2016년 5월 28일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 5월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Colistin sulfate, USP Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data” (PDF). 2016년 3월 3일. 2016년 3월 4일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 2월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Colistin-tobramycin combinations are superior to monotherapy concerning the killing of biofilm Pseudomonas aeruginosa”. 《The Journal of Infectious Diseases》 202 (10): 1585–1592. November 2010. doi:10.1086/656788. PMID 20942647.

- ↑ “Tolerance to the antimicrobial peptide colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is linked to metabolically active cells, and depends on the pmr and mexAB-oprM genes”. 《Molecular Microbiology》 68 (1): 223–240. April 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06152.x. PMID 18312276.

- ↑ “Selective labelling and eradication of antibiotic-tolerant bacterial populations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms”. 《Nature Communications》 7: 10750. February 2016. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710750C. doi:10.1038/ncomms10750. PMC 4762895. PMID 26892159.

- ↑ “Polymyxin-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolates: what is next?”. 《Emerging Infectious Diseases》 9 (8): 1025–1027. August 2003. doi:10.3201/eid0908.030052. PMC 3020604. PMID 12971377.

- ↑ 가 나 〈Molecular Basis of Antibiotic Resistance in Acinetobacter spp.〉. 《Acinetobacter Molecular Biology》. Caister Academic Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-306-43902-5. 2012년 2월 7일에 원본

|보존url=은|url=을 필요로 함 (도움말)에서 보존된 문서. - ↑ “Successful treatment of Acinetobacter meningitis with intrathecal polymyxin E”. 《The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy》 54 (1): 290–292. July 2004. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh289. PMID 15190037.

- ↑ “Intrathecal colistin for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventriculitis: report of a case with successful outcome”. 《Critical Care》 10 (6): 428. 2006. doi:10.1186/cc5088. PMC 1794456. PMID 17214907.

- ↑ “Colistin and rifampicin in the treatment of nosocomial infections from multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii”. 《The Journal of Infection》 53 (4): 274–278. October 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2005.11.019. PMID 16442632.

- ↑ “Is intraventricular colistin an effective and safe treatment for post-surgical ventriculitis in the intensive care unit?”. 《Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica》 50 (10): 1309–1310. November 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01126.x. PMID 17067336.

- ↑ “Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections”. 《The Lancet. Infectious Diseases》 6 (9): 589–601. September 2006. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(06)70580-1. PMID 16931410.

- ↑ 가 나 “Colomycin Injection”. 《Summary of Product Characteristics》. electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). 2016년 5월 18일. 2017년 7월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 6월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “COMMITTEE FOR VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCTS: COLISTIN: SUMMARY REPORT (2)” (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 2002. 2006년 7월 18일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Effects of blood pressure lowering in the acute phase of total anterior circulation infarcts and other stroke subtypes”. 《Cerebrovascular Diseases》 15 (4): 235–243. 2003. doi:10.1159/000069498. PMID 12686786.

- ↑ “In-vitro activity of the combination of colistin and rifampicin against multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii”. 《The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy》 41 (4): 494–495. April 1998. doi:10.1093/jac/41.4.494. PMID 9598783.

- ↑ “Combined colistin and rifampicin therapy for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: clinical outcome and adverse events”. 《Clinical Microbiology and Infection》 11 (8): 682–683. August 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01198.x. PMID 16008625.

- ↑ “In vitro assessment of colistin's antipseudomonal antimicrobial interactions with other antibiotics”. 《Clinical Microbiology and Infection》 5 (1): 32–36. January 1999. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00095.x. PMID 11856210.

- ↑ “Promixin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for Nebuliser Solution”. 《Patient Information Leafle》. electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). 2016년 1월 12일. 2017년 7월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Effectiveness of treatment with nebulized colistin in patients with COPD”. 《International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease》 12: 2909–2915. 2017. doi:10.2147/COPD.S138428. PMC 5634377. PMID 29042767.

- ↑ “Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study”. 《The Lancet. Infectious Diseases》 16 (2): 161–168. February 2016. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. PMID 26603172.

- ↑ “Resistance to the Antibiotic of Last Resort Is Silently Spreading”. 《The Atlantic》. 2017년 1월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 1월 12일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Apocalypse Pig Redux: Last-Resort Resistance in Europe”. 《Phenomena》. 2015년 12월 3일. 2016년 5월 28일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 5월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “First discovery in United States of colistin resistance in a human E. coli infection”. 《www.sciencedaily.com》. 2016년 5월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 5월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Emergence of Pan drug resistance amongst gram negative bacteria! The First case series from India”. December 2014.

- ↑ “New worry: Resistance to 'last antibiotic' surfaces in India”. 《The Times of India》. 2014년 12월 28일. 2014년 12월 31일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Colistin, mechanisms and prevalence of resistance”. 《Current Medical Research and Opinion》 31 (4): 707–721. April 2015. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1018989. PMID 25697677.

- ↑ “Discovery of first mcr-1 gene in E. coli bacteria found in a human in United States”. 《cdc.gov》. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016년 5월 31일. 2016년 7월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 7월 6일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Clinical use of colistin induces cross-resistance to host antimicrobials in Acinetobacter baumannii”. 《mBio》 4 (3): e00021–e00013. May 2013. doi:10.1128/mBio.00021-13. PMC 3663567. PMID 23695834.

- ↑ “The evolution of colistin resistance increases bacterial resistance to host antimicrobial peptides and virulence”. 《eLife》 12: e84395. April 2023. doi:10.7554/eLife.84395. PMC 10129329

|pmc=값 확인 필요 (도움말). PMID 37094804. - ↑ 가 나 “Common 'Superbug' Found to Disguise Resistance to Potent Antibiotic”. 《wsj.com》. Wall Street Journal. 2018년 3월 6일. 2018년 4월 3일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2018년 11월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Antimicrobial heteroresistance: an emerging field in need of clarity”. 《Clinical Microbiology Reviews》 28 (1): 191–207. January 2015. doi:10.1128/CMR.00058-14. PMC 4284305. PMID 25567227.

- ↑ 가 나 “Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Exhibiting Clinically Undetected Colistin Heteroresistance Leads to Treatment Failure in a Murine Model of Infection”. 《mBio》 9 (2): e02448–17. March 2018. doi:10.1128/mBio.02448-17. PMC 5844991. PMID 29511071.

- ↑ “Neurotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of colistin in patients with renal disease”. 《The New England Journal of Medicine》 266 (15): 759–762. April 1962. doi:10.1056/NEJM196204122661505. PMID 14008070.

- ↑ “Adverse effects of sodium colistimethate. Manifestations and specific reaction rates during 317 courses of therapy”. 《Annals of Internal Medicine》 72 (6): 857–868. June 1970. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-857. PMID 5448745.

- ↑ “Four years' experience of intravenous colomycin in an adult cystic fibrosis unit”. 《The European Respiratory Journal》 12 (3): 592–594. September 1998. doi:10.1183/09031936.98.12030592. PMID 9762785.

- ↑ “Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria”. 《International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents》 25 (1): 11–25. January 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.10.001. PMID 15620821.

- ↑ “The clinical use of colistin in patients with cystic fibrosis”. 《Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine》 7 (6): 434–440. November 2001. doi:10.1097/00063198-200111000-00013. PMID 11706322.

- ↑ “Safety and tolerability of bolus intravenous colistin in acute respiratory exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis”. 《The Annals of Pharmacotherapy》 34 (11): 1238–1242. November 2000. doi:10.1345/aph.19370. PMID 11098334.

- ↑ “A ten year review of colomycin”. 《Respiratory Medicine》 94 (7): 632–640. July 2000. doi:10.1053/rmed.2000.0834. PMID 10926333.

- ↑ “Colistin: an antimicrobial for the 21st century?”. 《Clinical Infectious Diseases》 35 (7): 901–902. October 2002. doi:10.1086/342570. PMID 12228836.

- ↑ “Hypoalbuminemia as a predictor of acute kidney injury during colistin treatment”. 《Scientific Reports》 8 (1): 11968. August 2018. Bibcode:2018NatSR...811968G. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30361-5. PMC 6086859. PMID 30097635.

- ↑ “Inhalation solutions: which one are allowed to be mixed? Physico-chemical compatibility of drug solutions in nebulizers”. 《Journal of Cystic Fibrosis》 5 (4): 205–213. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.007. PMID 16678502.

- ↑ “Nebulized colistin causes chest tightness in adults with cystic fibrosis”. 《Respiratory Medicine》 88 (2): 145–147. February 1994. doi:10.1016/0954-6111(94)90028-0. PMID 8146414.

- ↑ “Induced tolerance to nebulized colistin after severe reaction to the drug”. 《Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology》 17 (1): 59–61. 2007. PMID 17323867.

- ↑ “Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections”. 《The Lancet. Infectious Diseases》 6 (9): 589–601. September 2006. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1. PMID 16931410.

- ↑ “Pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulphonate and colistin in rats following an intravenous dose of colistin methanesulphonate”. 《The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy》 53 (5): 837–840. May 2004. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh167. PMID 15044428.

- ↑ “Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration”. 《Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy》 47 (5): 1766–1770. May 2003. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.5.1766-1770.2003. PMC 153303. PMID 12709357.

- ↑ “A new antibiotic 'colistin' produced by spore-forming soil bacteria”. 《J Antibiot (Tokyo)》 3. 1950.

- ↑ “Colistin: An overview”. 《UpToDate》. Wolters Kluwer. 2022년 11월 22일. 2016년 5월 31일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 6월 6일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections”. 《Clinical Infectious Diseases》 40 (9): 1333–1341. May 2005. doi:10.1086/429323. PMID 15825037.

- ↑ “How China is getting its farmers to kick their antibiotics habit”. Nature. 2020년 10월 21일. 2021년 8월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ 《Medicinal Natural Products》 Thi판. John Wiley & Sons. 2009.

참고 자료[편집]

- “Spread of antibiotic-resistance gene does not spell bacterial apocalypse — yet”. 《Nature》. December 2015. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.19037.

외부 링크[편집]

- “Colistimethate sodium”. 《Drug Information Portal》. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- “Colistin sulfate”. 《Drug Information Portal》. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- “Colistin topics page (bibliography)”. Science.gov.