사용자:배우는사람/문서:Flood myth

A flood myth or deluge myth is a symbolic narrative in which a great flood is sent by a deity, or deities, to destroy civilization in an act of divine retribution (응징). Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primeval waters found in certain creation myths, as the flood waters are described as a measure for the cleansing of humanity, in preparation for rebirth. Most flood myths also contain a culture hero, who strives to ensure this rebirth.[1] The flood myth motif is widespread among many cultures as seen in the Mesopotamian flood stories, the Puranas, Deucalion in Greek mythology, the Genesis flood narrative, and in the lore of the K'iche' and Maya peoples of Central America, and the Muisca people in South America.

Mythologies[편집]

The Mesopotamian flood stories concern the epics of Ziusudra, Gilgamesh, and Atrahasis. In the Sumerian King List, it relies on the flood motif to divide its history into preflood and postflood periods. The preflood kings had enormous lifespans, whereas postflood lifespans were much reduced. The Sumerian flood myth found in the Deluge tablet was the epic of Ziusudra, who heard the Divine Counsel to destroy humanity, in which he constructed a vessel that delivered him from great waters.[2] In the Atrahasis version, the flood is a river flood.[3]

Assyriologist George Smith translated the Babylonian account of the Great Flood in the 19th Century. Further discoveries produced several versions of the Mesopotamian flood myth, with the account that is closest to that in Genesis 6–9 found in a 700 BC Babylonian copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In this work, the hero, Gilgamesh, meets the immortal man, Utnapishtim, and the latter describes how the god, Ea, instructed him to build a huge vessel in anticipation of a deity-created flood that would destroy the world; the vessel was not only intended for Utnapishtim, but was built to also protect his family, his friends and animals.[4]

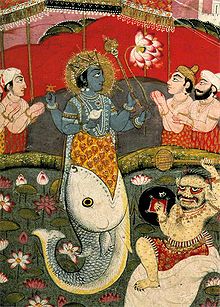

In Hindu mythology, texts such as the Satapatha Brahmana mention the puranic story of a great flood,[5] wherein the Matsya Avatar of Vishnu warns the first man, Manu, of the impending flood, and also advises him to build a giant boat.[6][7][8]

In the Genesis flood narrative, Yahweh decides to flood the earth because of the depth of the sinful state of mankind. Righteous Noah is given instructions to build an ark. When the ark is completed, Noah, his family, and representatives of all the animals of the earth are called upon to enter the ark. When the destructive flood begins, all life outside of the ark perishes. After the waters recede, all those aboard the ark disembark and have God's promise that He will never judge the earth with a flood again. He gives the rainbow as the sign of this promise.[9]

List of flood myths[편집]

A Flood myth or deluge myth is a mythical story of a great flood usually sent by a deity or deities to destroy civilization as an act of divine retribution. Flood myths are common across a wide range of cultures.

West Asia and Europe[편집]

Ancient Near East[편집]

Sumerian creation myth and flood myth: Zi-ud-sura[편집]

The earliest record of the Sumerian creation myth and flood myth is found on a single fragmentary tablet excavated in Nippur, sometimes called the Eridu Genesis. It is written in the Sumerian language and dated to around 1600 BC during the first Babylonian dynasty, where the language of writing and administration was still Sumerian. Other Sumerian creation myths from around this date are called the Barton Cylinder, the Debate between sheep and grain and the Debate between Winter and Summer, also found at Nippur.[10]

Summary

Where the tablet picks up, the gods An, Enlil, Enki and Ninhursanga create the black-headed people and create comfortable conditions for the animals to live and procreate. Then kingship descends from heaven and the first cities are founded: Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larsa, Sippar, and Shuruppak.

After a missing section in the tablet, we learn that the gods have decided not to save mankind from an impending flood. Zi-ud-sura, the king and gudug priest, learns of this. In the later Akkadian version, Ea, or Enki in Sumerian, the god of the waters, warns the hero (Atra-hasis in this case) and gives him instructions for the ark. This is missing in the Sumerian fragment, but a mention of Enki taking counsel with himself (자기 혼자서 생각하다, 신중히 생각하다) suggests that this is Enki's role in the Sumerian version as well.

When the tablet resumes it is describing the flood. A terrible storm rocks (요동시키다) the huge boat for seven days and seven nights, then Utu (the Sun god) appears and Zi-ud-sura creates an opening in the boat, prostrates himself, and sacrifices oxen and sheep.

After another break the text resumes: the flood is apparently over, the animals disembark and Zi-ud-sura prostrates himself before An (sky-god) and Enlil (chief of the gods), who give him eternal life and take him to dwell in Dilmun for "preserving the animals and the seed of mankind". The remainder of the poem is lost.[11]

Legacy

Two flood myths with many similarities to the Sumerian story are the Utnapishtim episode in the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Genesis flood narrative found in the Bible. The ancient Greeks have two very similar floods legends they are the Deucalion and The great Flood in Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid.

Ziusudra and Xisuthros

Zi-ud-sura is known to us from the following sources:

- From the Sumerian Flood myth discussed above.

- In reference to his immortality in some versions of The Death of Gilgamesh[12]

- Again in reference to his immortality in The Poem of Early Rulers[13]

- As Xisuthros (or Xisouthros, Ξίσουθρος) in Berossus' Hellenistic account of the Ancient Near East Flood myth, preserved in later excerpts.

- Xisuthros was also included in Berossus' king list, also preserved in later excerpts.

- As Ziusudra in the WB-62 recension of the Sumerian king list. This text diverges from all other extant king lists by listing the city of Shuruppak as a king, and including Ziusudra as "Shuruppak's" successor.[14]

- A later version of a document known as The Instructions of Shuruppak[15] refers to Ziusudra.[16]

In both of the late-dated king lists cited above, the name Zi-ud-sura was inserted immediately before a flood event included in all versions of the Sumerian king list, apparently creating a connection between the ancient Flood myth and a historic flood mentioned in the king list. However, no other king list mentions Zi-ud-sura.

See also

- Atra-Hasis

- Creation myth

- Deluge (mythology)

- Enûma Eliš

- Epic of Gilgamesh

- Gilgamesh flood myth

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Sumerian literature

External links

Flood story from the Akkadian Epic of Atrahasis[편집]

| Part of a series on |

| Mesopotamian mythology |

|---|

| Mesopotamian religion |

| Other traditions |

Atra-Hasis ("exceedingly wise") is the protagonist of an 18th century BCE Akkadian epic recorded in various versions on clay tablets. The Atra-Hasis tablets include both a creation myth and a flood account, which is one of three surviving Babylonian deluge stories. The name "Atra-Hasis" also appears on one of the Sumerian king lists as king of Shuruppak in the times before a flood.

The oldest known copy of the epic tradition concerning Atrahasis[17] can be dated by colophon (scribal identification) to the reign of Hammurabi’s great-grandson, Ammi-Saduqa (1646–1626 BCE), but various Old Babylonian fragments exist; it continued to be copied into the first millennium BCE. The Atrahasis story also exists in a later fragmentary Assyrian version, having been first rediscovered in the library of Ashurbanipal, but, because of the fragmentary condition of the tablets and ambiguous words, translations had been uncertain. Its fragments were assembled and translated first by George Smith as The Chaldean Account of Genesis; the name of its hero was corrected to Atra-Hasis by Heinrich Zimmern in 1899.

In 1965 W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard[18] published many additional texts belonging to the epic, including an Old Babylonian copy (written around 1650 BCE) which is our most complete surviving recension of the tale. These new texts greatly increased knowledge of the epic and were the basis for Lambert and Millard’s first English translation of the Atrahasis epic in something approaching entirety.[19] A further fragment has been recovered in Ugarit. Walter Burkert[20] traces the model drawn from Atrahasis to a corresponding passage, the division by lots of the air, underworld and sea among Zeus, Hades and Poseidon in the Iliad, in which “a resetting through which the foreign framework still shows”.

In its most complete surviving version, the Atrahasis epic is written on three tablets in Akkadian, the language of ancient Babylon.[21]

Synopsis

Tablet I contains a creation myth about the Sumerian gods Anu, Enlil, and Enki, gods of sky, wind, and water, “when gods were in the ways of men” according to its incipit. Following the Cleromancy (casting of lots), sky is ruled by Anu, earth by Enlil, and the freshwater sea by Enki. Enlil assigned junior divines[22] to do farm labor and maintain the rivers and canals, but after forty years the lesser gods or dingirs rebelled and refused to do strenuous labor. Instead of punishing the rebels, Enki, who is also the kind, wise counselor of the gods, suggested that humans be created to do the work. The mother goddess Mami is assigned the task of creating humans by shaping clay figurines mixed with the flesh and blood of the slain god Geshtu-E, “a god who had intelligence” (his name means “ear” or “wisdom”).[23] All the gods in turn spit upon the clay. After ten months, a specially made womb breaks open and humans are born. Tablet I continues with legends about overpopulation and plagues. Atrahasis is mentioned at the end of Tablet I.

Tablet II begins with more overpopulation of humans and the god Enlil sending first famine and drought at formulaic intervals of 1200 years to reduce the population. In this epic Enlil is depicted as a nasty capricious god while Enki is depicted as a kind helpful god, perhaps because priests of Enki were writing and copying the story. Tablet II is mostly damaged, but ends with Enlil's decision to destroy humankind with a flood and Enki bound by an oath to keep the plan secret.

Tablet III of the Atrahasis Epic contains the flood story. This is the part that was adapted in the Epic of Gilgamesh, tablet XI. Tablet III of Atrahasis tells how the god Enki warns the hero Atrahasis (“Extremely Wise”) of Shuruppak, speaking through a reed wall (suggestive of an oracle) to dismantle his house (perhaps to provide a construction site) and build a boat to escape the flood planned by the god Enlil to destroy humankind. The boat is to have a roof “like Apsu” (a subterranean, fresh water realm presided over by the god Enki), upper and lower decks, and to be sealed with bitumen. Atrahasis boards the boat with his family and animals and seals the door. The storm and flood begin. Even the gods are afraid. After seven days the flood ends and Atrahasis offers sacrifices to the gods. Enlil is furious with Enki for violating his oath. But Enki denies violating his oath and argues: “I made sure life was preserved.” Enki and Enlil agree on other means for controlling the human population.

Atrahasis in History

A few general histories can be attributed to the Mesopotamian Atrahasis by ancient sources; these should generally be considered mythology but they do give an insight into the possible origins of the character. The Epic of Gilgamesh labels Atrahasis as the son of Ubara-Tutu, king of Shuruppak, on tablet XI, ‘Gilgamesh spoke to Utnapishtim (Atrahasis), the Faraway… O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubara-Tutu’.[24] The Instructions of Shuruppak instead label Atrahasis (under the name Ziusudra) as the son of the eponymous Shuruppak, who himself is labelled as the son of Ubara-Tutu.[25] At this point we are left with two possible fathers: Ubara-Tutu or Shuruppak. Many available tablets comprising The Sumerian King Lists support The Epic of Gilgamesh by omitting Shuruppak as a ruler of Shuruppak. These lists imply an immediate flood after or during the rule of Ubara-Tutu. These lists also make no mention of Atrahasis under any name.[26] However WB-62 lists a different and rather interesting chronology – here Atrahasis is listed as a ruler of Shuruppak and gudug priest, preceded by his father Shuruppak who is in turn preceded by his father Ubara-Tutu. WB-62 would therefore lend support to The Instructions of Shuruppak and is peculiar in that it mentions both Shuruppak and Atrahasis. In any event it seems that Atrahasis was of royal blood; whether he himself ruled and in what way this would affect the chronology is debatable.

Literary inheritance

The Epic of Atrahasis provides additional information on the flood and flood hero that is omitted in Gilgamesh XI and other versions of the Ancient Near East flood story. According to Atrahasis III ii.40–47 the flood hero was at a banquet when the storm and flood began: “He invited his people…to a banquet… He sent his family on board. They ate and they drank. But he (Atrahasis) was in and out. He could not sit, could not crouch, for his heart was broken and he was vomiting gall.”

The flood story in the standard edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Chapter XI may have been paraphrased or copied verbatim from a non-extant, intermediate version the Epic of Atrahasis.[27] But editorial changes were made, some of which had long-term consequences. The sentence quoted above from Atrahasis III iv, lines 6–7: “Like dragonflies they have filled the river.” was changed in Gilgamesh XI line 123 to: “Like the spawn of fishes, they fill the sea.” However, see comments above.

Other editorial changes were made to the Atrahasis text. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, anthropomorphic descriptions of the gods are weakened. For example, Atrahasis OB III, 30–31 “The Anunnaki (the senior gods) [were sitt]ing in thirst and hunger.” was changed in Gilgamesh XI, 113 to “The gods feared the deluge.” Sentences in Atrahasis III iv were omitted in Gilgamesh, e.g. “She was surfeited with grief and thirsted for beer” and “From hunger they were suffering cramp.”[28]

See also

- Alan Millard

- Babylonian and Assyrian religion

- Flood myth

- Gilgamesh flood myth

- Noah's Ark

- Sumerian creation myth

- It has been stated by some that Geshtu-E was depicted as the engineer sacrifying himself during the opening sequence of Ridley Scott´s movie Prometheus which is related to the Akkadian myth, evidence supported by some archealogic comments made by some of the characters.

References

- W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard, Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood, Eisenbrauns, 1999, ISBN 1-57506-039-6.

- Q. Laessoe, “The Atrahasis Epic, A Babylonian History of Mankind”, Biblioteca Orientalis 13 [1956] 90–102.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay, The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1982, ISBN 0-8122-7805-4.

External links

Babylonian (Epic of Gilgamesh) - Gilgamesh flood myth: Utnapishtim[편집]

| |

| Material | clay |

|---|---|

| Size | Width: 15.24 cm (6.00 in) Breadth: 13.33 cm (5.25 in) Depth: 3.17 cm (1.25 in) |

| Writing | cuneiform |

| Created | 7th century BC |

| Period/culture | Neo-Assyrian |

| Discovered | Kouyunjik |

| Present location | Room 55, British Museum, London |

| Identification | K.3375 |

The Gilgamesh flood myth is a flood myth in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Many scholars believe that the flood myth was added to Tablet XI in the "standard version" of the Gilgamesh Epic by an editor who utilized the flood story from the Epic of Atrahasis.[29] A short reference to the flood myth is also present in the much older Sumerian Gilgamesh poems, from which the later Babylonian versions drew much of their inspiration and subject matter.

History

Gilgamesh’s supposed historical reign is believed to have been approximately 2700 BCE,[30] shortly before the earliest known written stories. The discovery of artifacts associated with Aga and Enmebaragesi of Kish, two other kings named in the stories, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh.[31]

The earliest Sumerian Gilgamesh poems date from as early as the Third dynasty of Ur (2100–2000 BC).[32] One of these poems mentions Gilgamesh’s journey to meet the flood hero, as well as a short version of the flood story.[33] The earliest Akkadian versions of the unified epic are dated to ca. 2000–1500 BC.[34] Due to the fragmentary nature of these Old Babylonian versions, it is unclear whether they included an expanded account of the flood myth; although one fragment definitely includes the story of Gilgamesh’s journey to meet Utnapishtim. The “standard” Akkadian version included a long version of the flood story and was edited by Sin-liqe-unninni sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC.[35]

Tablet eleven (XI), the flood tablet, about Utnapishtim

The Gilgamesh flood tablet XI contains additional story material besides the flood. The flood story was included because in it the flood hero Utnapishtim is granted immortality by the gods and that fits the immortality theme of the Epic. The main point seems to be that Utnapishtim was granted eternal life in unique, never to be repeated circumstances. As if to demonstrate this point, Utnapishtim challenges Gilgamesh to stay awake for six days and seven nights. However, as soon as Utnapishtim finishes speaking Gilgamesh falls asleep. Utnapishtim instructs his wife to bake a loaf of bread for every day he is asleep so that Gilgamesh cannot deny his failure. Gilgamesh, who wants to overcome death, cannot even conquer sleep.

As Gilgamesh is leaving, Utnapishtim's wife asks her husband to offer a parting gift. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh of a boxthorn-like plant at the very bottom of the ocean that will make him young again. Gilgamesh obtains the plant by binding stones to his feet so he can walk on the bottom of the sea. He recovers the plant and plans to test it on an old man when he returns to Uruk. Unfortunately, when Gilgamesh stops to bathe it is stolen by a serpent that sheds its skin as it departs, apparently reborn. Gilgamesh, having failed both chances, returns to Uruk, where the sight of its massive walls provokes him to praise this enduring work of mortal men. The implication may be that mortals can achieve immortality through lasting works of civilization and culture.

Flood myth section, (first 2/3 of Tablet XI)

Lines 1-203, Tablet XI [36] (note: with supplemental sub-titles and line numbers added for clarity)

The god Ea leaks the secret plan

- Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh a secret story that begins in the old city of Shuruppak on the banks of the Euphrates River.

- The "great gods" Anu, Enlil, Ninurta, Ennugi, and Ea were sworn to secrecy about their plan to cause the flood.

- But the god Ea (Sumerian god Enki) repeated the plan to Utnapishtim through a reed wall in a reed house.

- Ea commanded Utnapishtim to demolish his house and build a boat, regardless of the cost, to keep living beings alive.

- The boat must have equal dimensions with corresponding width and length and be covered over like Apsu boats.

- Utnapishtim promised to do what Ea commanded.

- He asked Ea what he should say to the city elders and the population.

- Ea tells him to say that Enlil has rejected him and he can no longer reside in the city or set foot in Enlil's territory.

- He should also say that he will go down to the Apsu "to live with my lord Ea".

- Note: 'Apsu' can refer to a fresh water marsh near the temple of Ea/Enki at the city of Eridu.[37]

- Ea will provide abundant rain, a profusion of fowl and fish, and a wealthy harvest of wheat and bread.

Building and launching the boat

- Carpenters, reed workers, and other people assembled one morning.

- [missing lines]

- Five days later, Utnapishtim laid out the exterior walls of the boat of 120 cubits.

- The sides of the superstructure had equal lengths of 120 cubits. He also made a drawing of the interior structure.

- The boat had six decks [?] divided into seven and nine compartments.

- Water plugs were driven into the middle part.

- Punting poles and other necessary things were laid in.

- Three times 3,600 units of raw bitumen were melted in a kiln and three times 3,600 units of oil were used in addition to two times 3,600 units of oil that were stored in the boat.

- Oxen and sheep were slaughtered and ale, beer, oil, and wine were distributed to the workmen, like at a new year's festival.

- When the boat was finished, the launching was very difficult. A runway of poles was used to slide the boat into the water.

- Two-thirds of the boat was in the water.

- Utnapishtim loaded his silver and gold into the boat.

- He loaded "all the living beings that I had."

- His relatives and craftsmen, and "all the beasts and animals of the field" boarded the boat.

- The time arrived, as stated by the god Shamash, to seal the entry door.

The storm

- Early in the morning at dawn a black cloud arose from the horizon.

- The weather was frightful.

- Utnapishtim boarded the boat and entrusted the boat and its contents to his boatmaster Puzurammurri who sealed the entry.

- The thunder god Adad rumbled in the cloud and storm gods Shullar and Hanish went over mountains and land.

- Erragal pulled out the mooring poles and the dikes overflowed.

- The Annunnaki gods lit up the land with their lightning.

- There was stunned shock at Adad's deeds which turned everything to blackness. The land was shattered like a pot.

- All day long the south wind blew rapidly and the water overwhelmed the people like an attack.

- No one could see his fellows. They could not recognize each other in the torrent.

- The gods were frightened by the flood, and retreated up to the Anu heaven. They cowered like dogs lying by the outer wall.

- Ishtar shrieked like a woman in childbirth.

- The Mistress of the Gods wailed that the old days had turned to clay because "I said evil things in the Assembly of the Gods, ordering a catastrophe to destroy my people who fill the sea like fish."

- The other gods were weeping with her and sat sobbing with grief, their lips burning, parched with thirst.

- The flood and wind lasted six days and six nights, flattening the land.

- On the seventh day, the storm was pounding [intermittently?] like a woman in labor.

Calm after the storm

- The sea calmed and the whirlwind and flood stopped. All day long there was quiet. All humans had turned to clay.

- The terrain was as flat as a roof top. Utnapishtim opened a window and felt fresh air on his face.

- He fell to his knees and sat weeping, tears streaming down his face. He looked for coastlines at the horizon and saw a region of land.

- The boat lodged firmly on mount Nimush which held the boat for several days, allowing no swaying.

- On the seventh day he released a dove which flew away, but came back to him. He released a swallow, but it also came back to him.

- He released a raven which was able to eat and scratch, and did not circle back to the boat.

- He then sent his livestock out in various directions.

The sacrifice

- He sacrificed a sheep and offered incense at a mountainous ziggurat where he placed 14 sacrificial vessels and poured reeds, cedar, and myrtle into the fire.

- The gods smelled the sweet odor of the sacrificial animal and gathered like flies over the sacrifice.

- Then the great goddess arrived, lifted up her flies (beads), and said

- "Ye gods, as surely as I shall not forget this lapis lazuli [amulet] around my neck, I shall be mindful of these days and never forget them! The gods may come to the sacrificial offering. But Enlil may not come, because he brought about the flood and annihilated my people without considering [the consequences]."

- When Enlil arrived, he saw the boat and became furious at the Igigi gods. He said "Where did a living being escape? No man was to survive the annihilation!"

- Ninurta spoke to Enlil saying "Who else but Ea could do such a thing? It is Ea who knew all of our plans."

- Ea spoke to Enlil saying "It was you, the Sage of the Gods. How could you bring about a flood without consideration?"

- Ea then accuses Enlil of sending a disproportionate punishment, and reminds him of the need for compassion.

- Ea denies leaking the god's secret plan to Atrahasis (= Utnapishtim), admitting only sending him a dream and deflecting Enlil's attention to the flood hero.

The flood hero and his wife are granted immortality and are transported far away

- He then boards a boat and grasping Utnapishtim's hand, helps him and his wife aboard where they kneel. Standing between Utnapishtim and his wife, he touches their foreheads and blesses them. "Formerly Utnapishtim was a human being, but now he and his wife have become gods like us. Let Utnapishtim reside far away, at the mouth of the rivers."

- Utnapishtim and his wife are transported and settled at the "mouth of the rivers".

Last third of Tablet XI-Outline

In addition to the flood story material, (lines 1–203), tablet XI contains the following flood story elements:

List of titled subparts, Tablet XI-(by Kovacs):[38]

- The Story of the Flood–(1-203)

- A Chance at Immortality–(204-240)

- Home Empty-Handed–(241-265)

- A Second Chance at Life–(266-309)

Comparison between Atrahasis and Gilgamesh

These are some of the sentences copied more or less directly from the Atrahasis version to the Gilgamesh epic:[39]

| Atrahasis Epic | Gilgamesh Epic, tablet XI |

|---|---|

| "Wall, listen to me." Atrahasis III,i,20 | "Wall, pay attention" Gilgamesh XI,22 |

| "Like the apsu you shall roof it" Atrahasis III,i,29 | "Like the apsu you shall roof it" Gilgamesh XI,31 |

| "I cannot live in [your city]" Atrahasis III,i,47 | "I cannot live in your city" Gilgamesh XI,40 |

| "Ninurta went forth making the dikes [overflow]" Atrahasis U rev,14 | "Ninurta went forth making the dikes overflow" Gilgamesh XI,102 |

| "One person could [not] see another" Atrahasis III,iii,13 | "One person could not see another" Gilgamesh XI,111 |

| "For seven days and seven nights came the storm" Atrahasis III,iv,24 | "Six days and seven nights the wind and storm flood" Gilgamesh XI,127 |

| "He offered [a sacrifice]" Atrahasis III,v,31 | "And offered a sacrifice" Gilgamesh XI,155 |

| "the lapis around my neck" Atrahasis III,vi,2 | "the lapis lazuli on my neck" Gilgamesh XI,164 |

| "How did man survive the destruction?" Atrahasis III,vi,10 | "No man was to survive the destruction" Gilgamesh XI,173 |

Material altered or omitted

The Epic of Atrahasis provides additional information on the flood and flood hero that is omitted in Gilgamesh XI and other versions of the Ancient Near East flood myth. According to Atrahasis III ii, lines 40–47 the flood hero was at a banquet when the storm and flood began: "He invited his people ... to a banquet ... He sent his family on board. They ate and they drank. But he (Atrahasis) was in and out. He could not sit, could not crouch, for his heart was broken and he was vomiting gall."[40]

According to Tigay, Atrahasis tablet III iv, lines 6–9 clearly identify the flood as a local river flood: "Like dragonflies they [dead bodies] have filled the river. Like a raft they have moved in to the edge [of the boat]. Like a raft they have moved in to the riverbank." The sentence "Like dragonflies they have filled the river." was changed in Gilgamesh XI line 123 to "Like the spawn of fishes, they fill the sea."[41] Tigay holds that we can see the mythmaker's hand at work here, changing a local river flood into an ocean deluge.

Most other authorities interpret the Atrahasis flood as universal. A. R. George, and Lambert and Millard make it clear that the gods' intention in Atrahasis is to "wipe out mankind".[42] The flood destroys "all of the earth".[43] The use of a comparable metaphor in the Gilgamesh epic suggests that the reference to "dragonflies [filling] the river" is simply an evocative image of death rather than a literal description of the flood[44] However, the local river flood in Atrahasis could accomplish destruction of all "mankind" and "all of the earth" if the scope of "mankind" is limited to all of the people living on "all of the land" of the flood plains in the lower river valley known to the Atrahasis writer.

Other editorial changes were made to the Atrahasis text in Gilgamesh to lessen the suggestion that the gods may have experienced human needs. For example, Atrahasis OB III, 30–31 "The Anunnaki, the great gods [were sitt]ing in thirst and hunger" was changed in Gilgamesh XI, line 113 to "The gods feared the deluge." Sentences in Atrahasis III iv were omitted in Gilgamesh, e.g. "She was surfeited with grief and thirsted for beer" and "From hunger they were suffering cramp."[45]

These and other editorial changes to Atrahasis are documented and described in the book by Prof. Tigay (see below) who is associate professor of Hebrew and Semitic Languages and Literature in the University of Pennsylvania. Prof. Tigay comments: "The dropping of individual lines between others which are preserved, but are not synonymous with them, appears to be a more deliberate editorial act. These lines share a common theme, the hunger and thirst of the gods during the flood."[45]

Although the 18th century BC copy of the Atrahasis (Atra-Hasis) epic post-dates the early Gilgamesh epic, we do not know whether the Old-Akkadian Gilgamesh tablets included the flood story, because of the fragmentary nature of surviving tablets. Some scholars argue that they did not.[46] Tigay, for example, maintains that three major additions to the Gilgamesh epic, namely the prologue, the flood story (tablet XI), and tablet XII, were added by an editor or editors, possibly by Sin-leqi-unninni, to whom the entire epic was later attributed. According to this view, the flood story in tablet XI was based on a late version of the Atrahasis story.[47]

Alternative translations

As with most translations, especially from an ancient, dead language, scholars differ on the meaning of ambiguous sentences.

For example, line 57 in Gilgamesh XI is usually translated (with reference to the boat) "ten rods the height of her sides",[48] or "its walls were each 10 times 12 cubits in height".[49] A rod was a dozen cubits, and a Sumerian cubit was about 20 inches. Hence these translations imply that the boat was about 200 feet high, which would be impractical[50] with the technology in Gilgamesh's time (about 2700 BC).[51] There is no Akkadian word for "height" in line 57. The sentence literally reads "Ten dozen-cubits each I-raised its-walls."[52] A similar example from an unrelated house building tablet reads: "he shall build the wall [of the house] and raise it four ninda and two cubits." This measurement (about 83 feet) means wall length not height.[53]

Line 142 in Gilgamesh XI is usually translated "Mount Niṣir held the boat, allowing no motion." Niṣir is often spelled Nimush.[54] The Akkadian words translated "Mount Niṣir" are "KUR-ú KUR ni-ṣir".[55] The word KUR is capitalized because it was a Sumerian word and could mean hill or country.[56] The first KUR is followed by a phonetic complement -ú which indicates that KUR-ú is to be read in Akkadian as šadú (hill) and not as mātu (country). Since šadú (hill) could also be translated as mountain in Akkadian and scholars knew the Biblical expression Mount Ararat, it has become customary to translate šadú as mountain or mount. The flood hero was Sumerian, according to the WB-62 Sumerian King List,[57] and in Sumerian the word KUR meant hill or country, not mountain. The second KUR lacks a phonetic complement and is therefore read in Akkadian as mātu (country). Hence, the entire clause reads "The hill/mound country niṣir held the boat".

Lines 146-147 in Gilgamesh XI are usually translated "I ... made sacrifice, incense I placed on the peak of the mountain."[58] Similarly "I poured out a libation on the peak of the mountain."[59] But Kovacs[60] provides this translation of line 156: "I offered incense in front of the mountain-ziggurat." Parpola provides the original Akkadian for this sentence: "áš-kun sur-qin-nu ina UGU ziq-qur-rat KUR-i"[61] Áš-kun means I-placed; sur-qin-nu means offering; ina-(the preposition) means on-(upon); UGU means top-of; ziq-qur-rat means temple tower; and KUR-i means hilly. Parpola's glossary (page 145) defines ziq-qur-rat as "temple tower, ziggurat" and refers to line 157 so he translates ziq-qur-rat as temple tower in this context. The sentence literally reads "I placed an offering on top of a hilly ziggurat." A ziggurat was an elevated platform or temple tower where priests made offerings to the temple god. Most translators of line 157 disregard ziq-qur-rat as a redundant metaphor for peak. There is no authority for this other than previous translations of line 157.[62] Kovacs' translation retains the word ziggurat on page 102.

One of the Sumerian cities with a ziggurat was Eridu located on the southern branch of the Euphrates River next to a large swampy low-lying depression known as the apsû.[63] The only ziggurat at Eridu was at the temple of the god Ea (Enki), known as the apsû-house.[64] In Gilgamesh XI, line 42 the flood hero said "I will go down [the river] to the apsû to live with Ea, my Lord."[65]

Lines 189–192 (lines 198–201) in Gilgamesh XI are usually translated "Then godEnlil came aboard the boat. He took hold of my hand and brought me on board. He brought aboard my wife and made her kneel at my side. Standing between us, he touched our foreheads to bless us."[66] In the first sentence "Then dingir-kabtu came aboard the boat" the Akkadian determinative dingir is usually translated as "god", but can also mean "priest"[67] Dingir-kabtu literally means "divine important-person".[68] Translating this as Enlil is the translator's conjecture.

See also

Bibliography

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. (1982), 《The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic》, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, ISBN 0-8122-7805-4

- W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard, Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood, Eisenbrauns, 1999, ISBN 1-57506-039-6.

- George, Andrew R., trans. & edit. (1999 (reprinted with corrections 2003), 《The Epic of Gilgamesh》, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-044919-1

- Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. (1985,1989), 《The Epic of Gilgamesh》, Stanford University Press: Stanford, California, ISBN 0-8047-1711-7 Glossary, Appendices, Appendix (Chapter XII=Tablet XII). A line-by-line translation (Chapters I-XI).

- Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius (1997), 《The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh》, The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, ISBN 951-45-7760-4 (Volume 1) in the original Akkadian cuneiform and transliteration. Commentary and glossary are in English

- Heidel, Alexander (1946), 《The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels》, University of Chicago, ISBN 0-226-32398-6

- Bailey, Lloyd R. (1989), 《Noah, the Person and the Story》, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-637-6

External links

- (영어) Gilgamesh - Curlie

- Comparison of equivalent lines in six ancient versions of the flood story

- Ancient Near East flood myths All texts: (Ziusudra, Atrahasis, Gilgamesh, Genesis, Berossus), commentary, and a table with parallels

- Gilgamesh Tablet XI (The Flood Chapter)

| 이전 15: Early writing tablet |

A History of the World in 100 Objects Object 16 |

이후 17: en:Rhind Mathematical Papyrus |

Utnapishtim (or Utanapishtim) is a character in Gilgamesh epic who is asked by Enki, (Ea) to abandon his world possessions and create a giant ship to be called The Preserver of Life. He was also tasked with bringing his wife, family, and relatives along with the craftsmen of his village, baby animals and grains.[69] The oncoming flood would wipe out all animals and humans that were not on the ship, similar to that of the later Noah's Ark story. After twelve days on the water, Utanapishtim opened the hatch of his ship to look around and saw the slopes of Mount Nisir, where he rested his ship for seven days. On the seventh day, he sent a dove out to see if the water had receded, and the dove could find nothing but water, so it returned. Then he sent out a swallow, and just as before, it returned, having found nothing. Finally, Utanapishtim sent out a raven, and the raven saw that the waters had receded, so it circled around, but did not return. Utanapishtim then set all the animals free, and made a sacrifice to the gods. The gods came, and because he had preserved the seed of man while remaining loyal and trusting of his gods, Utanapishtim and his wife were given immortality, as well as a place among the heavenly gods.

Role in the epic

In the Epic, overcome with the death of his friend Enkidu, the hero Gilgamesh sets out on a series of journeys to search for his ancestor Utanapishtim (xisouthros) who lives at the mouth of the rivers and has been given eternal life. Utnapishtim counsels Gilgamesh to abandon his search for immortality but tells him about a plant that can make him young again. Gilgamesh obtains the plant from the bottom of a river but a snake steals it, and Gilgamesh returns home to the city of Uruk having abandoned hope of either immortality or renewed youth.

See also

Classical Antiquity[편집]

Ancient Greek flood myths[편집]

Greek mythology describes three floods, the flood of Ogyges, the flood of Deucalion, and the flood of Dardanus. Two of the Greek Ages of Man concluded with a flood: The Ogygian Deluge ended the Silver Age, and the flood of Deucalion ended the First Bronze Age (Heroic age). In addition to these floods, Greek mythology says the world was also periodically destroyed by fire. See Phaëton.

Flood of Ogyges[편집]

| "Many great deluges have taken place during the nine thousand years, for that is the number of years which have elapsed since the time of which I am speaking; and during all of this time and through so many changes, there has never been any considerable accumulation of the soil coming down from the mountains, as in other places, but the earth has fallen away all round and sunk out of sight. The consequence is, that in comparison of what then was, there are remaining only the bones of the wasted body, as they may be called, as in the case of small islands, all the richer and softer parts of the soil having fallen away, and the mere skeleton of the land being left." |

| Plato’s Critias (111b)[70] |

The Ogygian flood is so called because it occurred in the time of Ogyges,[71] a mythical king of Attica. The name "Ogyges" and "Ogygian" is synonymous with "primeval", "primal" and "earliest dawn". Others say he was the founder and king of Thebes. In many traditions the Ogygian flood is said to have covered the whole world and was so devastating that Attica remained without kings until the reign of Cecrops.[72]

Plato in his Laws, Book III,[73] argues that this flood had occurred ten thousand years[74] before his time, as opposed to only "one or two thousand years that have elapsed" since the discovery of music, and other inventions. Also in Timaeus (22) and in Critias (111-112) he describes the "great deluge of all" as having been preceded by 9,000 years of history before the time of his contemporary Solon, during the 10th millennium BCE. In addition, the texts report that "many great deluges have taken place during the nine thousand years" since Athens and Atlantis were preeminent.[75]

Flood of Deucalion[편집]

The Deucalion legend as told by the Bibliotheca has some similarity to other deluge myths such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the story of Noah's Ark. The titan Prometheus advised his son Deucalion to build a chest. All other men perished except for a few who escaped to high mountains. The mountains in Thessaly were parted, and all the world beyond the Isthmus and Peloponnese was overwhelmed. Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha, after floating in the chest for nine days and nights, landed on Parnassus. An older version of the story told by Hellanicus has Deucalion's "ark" landing on Mount Othrys in Thessaly. Another account has him landing on a peak, probably Phouka, in Argolis, later called Nemea. When the rains ceased, he sacrificed to Zeus. Then, at the bidding of Zeus, he threw stones behind him, and they became men, and the stones Pyrrha threw became women. The Bibliotheca gives this as an etymology for Greek Laos "people" as derived from laas "stone".[76] The Megarians told that Megarus, son of Zeus and a Sithnid nymph, escaped Deucalion's flood by swimming to the top of Mount Gerania, guided by the cries of cranes.[77]

Flood of Deucalion from The Theogony of the Bibliotheca'

According to the Theogony of the Bibliotheca, Prometheus moulded men out of water and earth and gave them fire which, unknown to Zeus, he had hidden in a stalk of fennel. When Zeus learned of it, he ordered Hephaestus to nail Prometheus to Mount Caucasus, a Scythian mountain. Prometheus was nailed to the mountain and kept bound for many years. Every day an eagle swooped on him and devoured the lobes of his liver, which grew by night. That was the penalty that Prometheus paid for the theft of fire until Hercules afterwards released him.

Prometheus had a son Deucalion. He reigning in the regions about Phthia, married Pyrrha, the daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora, the first woman fashioned by the gods. And when Zeus would destroy the men of the Bronze Age, Deucalion by the advice of Prometheus constructed a chest, and having stored it with provisions he embarked in it with Pyrrha. But Zeus by pouring heavy rain from heaven flooded the greater part of Greece, so that all men were destroyed, except a few who fled to the high mountains in the neighbourhood and Peloponnesus was overwhelmed. But Deucalion, floating in the chest over the sea for nine days and as many nights, drifted to Parnassus, and there, when the rain ceased, he landed and sacrificed to Zeus, the god of Escape. And Zeus sent Hermes to him and allowed him to choose what he would, and he chose to get men.

At the bidding of Zeus he took up stones and threw them over his head, and the stones Deucalion threw became men, and the stones Pyrrha threw became women. Hence people were called metaphorically people (Laos) from laas, "a stone." And Deucalion had children by Pyrrha, first Hellen, whose father some say was Zeus, and second Amphictyon, who reigned over Attica after Cranaus, and third a daughter Protogonia, who became the mother of Aethlius by Zeus. Hellen had Dorus, Xuthus, and Aeolus by a nymph Orseis. Those who were called Greeks he named Hellenes after himself, and divided the country among his sons. Xuthus received Peloponnese and begat Achaeus and Ion by Creusa, daughter of Erechtheus, and from Achaeus and Ion the Achaeans and lonians derive their names. Dorus received the country over against Peloponnese and called the settlers Dorians after himself.

Aeolus reigned over the regions about Thessaly and named the inhabitants Aeolians. He married Enarete, daughter of Deimachus, and begat seven sons, Cretheus, Sisyphus, Athamas, Salmoneus, Deion, Magnes, Perieres, and five daughters, Canace, Alcyone, Pisidice, Calyce, Perimede. Perimede had Hippodamas and Orestes by Achelous; and Pisidice had Antiphus and Actor by Myrmidon. Alcyone was married by Ceyx, son of Lucifer. These perished by reason of their pride, for he said that his wife was Hera, and she said that her husband was Zeus. But Zeus turned them into birds; her he made a kingfisher (alcyon) and him a gannet (ceyx).

Flood of Dardanus[편집]

This one has the same basic story line. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Dardanus left Pheneus in Arcadia to colonize a land in the North-East Aegean Sea. When the Dardanus' deluge occurred, the land was flooded and the mountain where he and his family survived formed the island of Samothrace. He left Samothrace on an inflated skin to the opposite shores of Asia Minor and settled on Mount Ida. Due to the fear of another flood, they refrained from building a city and lived in the open for fifty years. His grandson Tros eventually moved from the highlands down to a large plain, on a hill that had many rivers flowing down from Ida above. There he built a city, which was named Troy after him.[78]

Medieval Europe[편집]

Germanic: The Louse and the Flea[편집]

The Louse and the Flea or Little Louse and Little Flea is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm, number 30.[79]

It is Aarne-Thompson type 2022, An Animal Mourns the Death of a Spouse,[80] and takes the form of a chain tale, sometimes known as a cumulative tale.

Synopsis

A louse and a flea are married until the louse drowns while brewing. The flea mourns, inspiring a door to ask why and start creaking, which inspires a broom to ask why and start sweeping -- through a sequence of objects until a spring overflows at the news and drowns them all.

External links

- "Mourning the Death of a Spouse:chain tales of Aarne-Thompson type 2022" by D.L. Ashliman

Irish: Lebor Gabála Érenn - Cessair[편집]

Cessair

This book, according to Macalister's scheme, constitutes the first interpolation in the Liber Occupationis. Cessair is the granddaughter of the Biblical Noah, who advises her and her father, Bith, to flee to the western edge of the world on account of the impending Flood. They set out in three ships, but when they arrive in Ireland two of the ships are lost. The only survivors are Cessair, forty-nine other women, and three men (Cessair's husband Fintán mac Bóchra, her father Bith, and the pilot Ladra). The women are divided among the men, Fintán taking Cessair and sixteen women, Bith taking Cessair's companion Bairrfhind and sixteen women, and Ladra taking the remaining sixteen women. Ladra, however, soon dies (the first man to be buried on Irish soil). Forty days later the Flood ensues. Fintán alone survives by spending a year under the waters in a cave called "Fintán's Grave". Afterwards known as "The White Ancient", he lives for 5500 years after the Deluge and witnesses the later settlements of the island in the guises of a salmon, an eagle and a hawk.

Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland) is the Middle Irish title of a loose collection of poems and prose narratives recounting the mythical origins and history of the Irish from the creation of the world down to the Middle Ages. An important record of the folkloric history of Ireland, it was compiled and edited by an anonymous scholar in the 11th century, and might be described as a mélange of mythology, legend, history, folklore and Christian historiography. It is usually known in English as The Book of Invasions or The Book of Conquests, and in Modern Irish as Leabhar Gabhála Éireann or Leabhar Gabhála na hÉireann.

Origins

Purporting to be a literal and accurate account of the history of the Irish, Lebor Gabála Érenn (hereinafter abbreviated as LGE) may be seen as an attempt to provide the Irish with a written history comparable to that which the Israelites provided for themselves in the Old Testament. Drawing upon the pagan myths of Celtic Ireland — both Gaelic and pre-Gaelic — but reinterpreting them in the light of Judaeo-Christian theology and historiography, it describes how the island was subjected to a succession of invasions, each one adding a new chapter to the nation's history. Biblical paradigms provided the mythologers with ready-made stories which could be adapted to their purpose. Thus we find the ancestors of the Irish enslaved in a foreign land, or fleeing into exile, or wandering in the wilderness, or sighting the "Promised Land" from afar.

Four Christian works in particular seem to have had a significant bearing on the formation of LGE:

- St Augustine's De Civitate Dei, The City of God, (413-426 AD)

- Orosius's Historiae adversum paganos, "Histories," (417)

- Eusebius's Chronicon, translated into Latin by St Jerome as the Temporum liber (379)

- Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae ("Etymologies"), or Origines ("Origins") (early 7th century)

The pre-Christian elements, however, were never entirely effaced. One of the poems in LGE, for instance, recounts how goddesses from among the Tuatha Dé Danann took Gaelic husbands when the Gael invaded and colonised Ireland. Furthermore, the pattern of successive invasions which LGE preserves is curiously reminiscent of Timagenes of Alexandria's account of the origins of another Celtic people, the Gauls of continental Europe. Cited by the 4th-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus, Timagenes (1st century BC) describes how the ancestors of the Gauls were driven from their native lands in eastern Europe by a succession of wars and floods.[81]

Numerous fragments of Irish pseudohistory are scattered throughout the 7th and 8th centuries, but the earliest extant account is to be found in the Historia Brittonum or "History of the Britons," considered by some to have been written by the Welsh priest Nennius in 829-830. This text gives two separate accounts of early Irish history. The first consists of a series of successive colonisations from Iberia by the pre-Gaelic races of Ireland, all of which found their way into LGE. The second recounts the origins of the Gael themselves, and tells how they in turn came to be the masters of the country and the ancestors of all the Irish.

These two stories continued to be enriched and elaborated upon by Irish bards throughout the 9th century. In the 10th and 11th centuries, several long historical poems were written that were later incorporated into the scheme of LGE. However, most of the poems on which the original version of LGE was based were written by the following four poets:

- Eochaidh Ua Floinn (936-1004) from Armagh – Poems 30, 41, 53, 65, 98, 109, 111

- Flann Mainistrech mac Echthigrin (died 1056), lector and historian of Monasterboice Abbey – Poems ?42, 56, 67, ?82

- Tanaide (died c. 1075) – Poems 47, 54, 86

- Gilla Cómáin mac Gilla Samthainde (fl. 1072) – Poems 13, 96, 115

It was late in the 11th century that a single anonymous scholar appears to have brought together these and numerous other poems and fitted them into an elaborate prose framework - partly of his own composition and partly drawn from older, no longer extant sources - which paraphrased and enlarged upon the verse. The result was the earliest version of LGE. It was written in Middle Irish, a form of Irish Gaelic used between 900 and 1200.

Textual variants and sources

From the beginning, LGE proved to be an enormously popular and influential document, quickly acquiring canonical status. Older texts were altered to bring their narratives into closer accord with its version of history, and numerous new poems were written and inserted into it. Within a century of its compilation there existed a plethora of copies and revisions, with as many as 136 poems between them. Five recensions of LGE are now extant, surviving in more than a dozen medieval manuscripts:

- First Redaction (R¹): preserved in The Book of Leinster (c. 1150) and The Book of Fermoy (1373).

- Míniugud (Min): this recension is closely related to the Second Redaction. It is probably older than the surviving MSS of that redaction, though not older than the now lost exemplar on which those MSS were based. The surviving sources are suffixed to copies of the Second Redaction.

- Second Redaction (R²): survives in no less than seven separate texts, the best known of which is The Great Book of Lecan (1418).

- Third Redaction (R³): preserved in both The Book of Ballymote (1391) and The Great Book of Lecan.

- O'Clery's Redaction (K): written in 1631 by Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, a Franciscan scribe and one of the Four Masters. Unlike the earlier versions of LGE, this redaction is in Early Modern Irish but was admitted as an independent redaction by Macalister because there are indications that the author had access to sources which are no longer extant and which were not used by the compilers of the other four redactions. The work was compiled in the convent of Lisgool, near Enniskillen. O'Clery was assisted by Gillapatrick O'Luinin and Peregrine O'Clery (Michael O Clery's third cousin once removed, and one of the Four Masters).

The following table summarizes the extant manuscripts that contain versions of LGE. Most of the abbreviations used are taken from R. A. S. Macalister's critical edition of the work (see references for details):

| Sigla | Manuscript | Location | Redactions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Stowe A.2.4 | Royal Irish Academy | R² | A direct and poor copy of D |

| B | The Book of Ballymote | Royal Irish Academy | R³ | B lost one folio after β, β¹ and β² were derived from it |

| β | H.2.4 | Trinity College, Dublin | R³ | A transcript of B made in 1728 by Richard Tipper |

| β¹ | H.1.15 | Trinity College, Dublin | R³ | A copy, made around 1745 by Tadgh Ó Neachtáin, of a lost transcript of B |

| β² | Stowe D.3.2 | Royal Irish Academy | R³ | An anonymous copy of the same lost transcript of B |

| D | Stowe D.4.3 | Royal Irish Academy | R² | |

| E | E.3.5. no. 2 | Trinity College, Dublin | R² | |

| F¹ | The Book of Fermoy | Royal Irish Academy | R¹ | F¹ and F² are parts of one dismembered MS, F |

| F² | Stowe D.3.1 | Royal Irish Academy | R¹ | |

| H | H.2.15. no. 1 | Trinity College, Dublin | R³ | |

| L | The Book of Leinster | Trinity College, Dublin | R¹ | |

| Λ | The Book of Lecan | Royal Irish Academy | R², Min | First text of LGE in The Book of Lecan |

| M | The Book of Lecan | Royal Irish Academy | R³ | Second text of LGE in The Book of Lecan |

| P | P.10266 | National Library of Ireland | R² | |

| R | Rawl.B.512 | Bodleian Library | R², Min | Only the prose text is written out in full: the poems are truncated |

| V¹ | Stowe D.5.1 | Royal Irish Academy | R², Min | V¹, V² and V³ are parts of one dismembered MS, V |

| V² | Stowe D.4.1 | Royal Irish Academy | R², Min | |

| V³ | Stowe D.1.3 | Royal Irish Academy | R², Min | |

| K¹ | 23 K 32 | Royal Irish Academy | K | Fair copy of the author Michael O Clery's autograph |

- K is contained in several paper manuscripts, but K¹, the "authoritative autograph", takes precedence.[82]

Modern criticism

For many centuries LGE was accepted without question as an accurate and reliable account of the history of Ireland. As late as the 17th century, Geoffrey Keating drew on it while writing his history of Ireland, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, and it was also used extensively by the authors of the Annals of the Four Masters. In 1905 Charles Squire defended the antiquity of these legends with this statement: "The scribes of the earlier Gaelic manuscripts very often found, in the documents from which they themselves were copying, words so archaic as to be unintelligible to the readers of their own period. To render them comprehensible, they were obliged to insert marginal notes which explained these obsolete words by reference to other manuscripts more ancient still".[83] Recently, however, the work has been subjected to greater critical scrutiny. One contemporary scholar has placed it in "the tradition of historical fabrication or pseudohistory";[84] another has written of its "generally spurious character" and has drawn attention to its many "fictions", while acknowledging that it "embodies some popular traditions.[85] The Irish archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister, who translated the work into English, was particularly dismissive of it: "There is not a single element of genuine historical detail, in the strict sense of the word, anywhere in the whole compilation".[86]

While scholars are still highly critical of the work, there is a general consensus that LGE does contain an account of the early history of Ireland, albeit a distorted one. The most contested claim in the work is the assertion that the Gaelic conquest took place in the remote past—around 1500 BC—and that all the inhabitants of Christian Ireland were descendants of these early Gaelic invaders. O'Rahilly, however, believed that the Gaelic conquest - depicted in LGE as the Milesian settlement - was the latest of the Celtic occupations of Ireland, taking place probably after 150 BC, and that many of Ireland's pre-Gaelic peoples continued to flourish for centuries after it.[87]

The British poet and mythologist Robert Graves may be cited as one of the relatively few modern scholars who did not share the scepticism of Macalister and O'Rahilly. In his seminal work The White Goddess (1948), Graves argued that ancient knowledge was transmitted orally from generation to generation by the druids of pre-literate Ireland. Taking issue with Macalister, with whom he corresponded on this and other matters, he declared some of LGE's traditions "archaeologically plausible".[88] The White Goddess itself has been the subject of critical and skeptical comment; nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that Graves did find some striking links between Celtic and Near Eastern mythology that are difficult to explain unless one is willing to accept that myths brought to Ireland centuries before the introduction of writing were preserved and transmitted accurately by word of mouth before being written down in the Christian Era.[89]

LGE was translated into French in 1884. The first complete English translation was made by R. A. Stewart Macalister between 1937 and 1942. It was accompanied by an apparatus criticus, Macalister's own notes and an introduction, in which he made clear his own view that LGE was a conflation of two originally independent works: a History of the Gaedil, modelled after the history of the Israelites as set forth in the Old Testament, and an account of several pre-Gaelic settlements of Ireland (to the historicity of which Macalister gave very little credence). The latter was then inserted into the middle of the other work, interrupting it at a crucial point of the narrative. Macalister theorized that the quasi-Biblical text had been a scholarly Latin work entitled Liber Occupationis Hiberniae ("The Book of the Taking of Ireland"), thus explaining why the Middle Irish title of LGE refers to only one "taking", while the text recounts more than half a dozen.

Contents

There now follows a brief outline of the text of LGE. The work can be divided into ten "books":

Genesis

A retelling of the familiar Judaeo-Christian story of the creation, the fall of Man and the early history of the world. In addition to Genesis, the author draws upon several recondite works for many of his details (e.g. the Syriac Cave of Treasures), as well as the four Christian works mentioned earlier (i.e. The City of God, etc.).

Early history of the Gaels

A pseudo-Biblical account of the origin of the Gaels as the descendants of the Scythian prince Fénius Farsaid, one of seventy-two chieftains who built the Tower of Babel. His grandson Goídel Glas, whose mother is Scota, daughter of a Pharaoh of Egypt, creates the Irish language from the original seventy-two languages that arose at the time of the dispersal of the nations. His descendants, the Gaels, undergo a series of trials and tribulations that are clearly modelled on those with which the Israelites are tried in the Old Testament. They flourish in Egypt at the time of Moses and leave during the Exodus; they wander the world for four hundred and forty years before eventually settling in the Iberian Peninsula. There, Goídel's descendant Breogán founds a city called Brigantia, and builds a tower from the top of which his son Íth glimpses Ireland. Brigantia can probably be identified with Corunna, north-west Galicia, known as Brigantium in Roman times;[90] A Roman lighthouse there known as the Tower of Hercules has been claimed to have been built on the site of Breogán's tower.[91]

Cessair

This book, according to Macalister's scheme, constitutes the first interpolation in the Liber Occupationis. Cessair is the granddaughter of the Biblical Noah, who advises her and her father, Bith, to flee to the western edge of the world on account of the impending Flood. They set out in three ships, but when they arrive in Ireland two of the ships are lost. The only survivors are Cessair, forty-nine other women, and three men (Cessair's husband Fintán mac Bóchra, her father Bith, and the pilot Ladra). The women are divided among the men, Fintán taking Cessair and sixteen women, Bith taking Cessair's companion Bairrfhind and sixteen women, and Ladra taking the remaining sixteen women. Ladra, however, soon dies (the first man to be buried on Irish soil). Forty days later the Flood ensues. Fintán alone survives by spending a year under the waters in a cave called "Fintán's Grave". Afterwards known as "The White Ancient", he lives for 5500 years after the Deluge and witnesses the later settlements of the island in the guises of a salmon, an eagle and a hawk.

Partholón

Three hundred years after the Flood, Partholón, who, like the Gaels, is a descendant of Noah's son Japheth, settles in Ireland with his three sons and their people. After ten years of peace, war breaks out with the Fomorians, a race of evil seafarers led by Cichol Gricenchos. The Partholonians are victorious, but their victory is short-lived. In a single week, they are wiped out by a plague — five thousand men and four thousand women — and are buried on the Plain of Elta to the southwest of Dublin, in an area that is still called Tallaght, which means "plague grave". A single man survives the plague, Tuan mac Cairill, who (like Fintán mac Bóchra) survives for centuries and undergoes a succession of metamorphoses, so that he can act as a witness of later Irish history. This book also includes the story of Delgnat, Partholón's wife, who commits adultery with a henchman.

Nemed

Thirty years after the extinction of the Partholonians, Ireland is settled by the people of Nemed, whose great-grandfather was a brother of Partholón's. During their occupation, the land is once again ravaged by the Fomorians and a lengthy war ensues. Nemed wins three great battles against the Fomorians, but after his death his people are subjugated by two Fomorian leaders, Morc and Conand. Eventually, however, they rise up and assault Conand's Tower on Tory Island. They are victorious, but an ensuing sea battle against Morc results in the destruction of both armies. A flood covers Ireland, wiping out most of the Nemedians. A handful of survivors are scattered to the four corners of the world.

Fir Bolg

One group of the seed of Nemed settled in Greece, where they were enslaved. Two hundred and thirty years after Nemed they flee and return to Ireland. There they separate into three nations: the Fir Bolg, Fir Domnann and the Fir Gálioin. They hold Ireland for just thirty-seven years before the invasion of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuatha Dé Danann are descendants of another group of the scattered seed of Nemed. They return to Ireland from the far north, where they have learned the arts of pagan magic and druidry, on or about May 1. They contest the ownership of Ireland with the Fir Bolg and their allies in the First Battle of Moytura (or Mag Tuired). The Tuatha Dé are victorious and drive the Fir Bolg into exile among the neighbouring islands. But Nuada, the king of the Tuatha Dé, loses his right arm in the battle and is forced to renounce his crown. For seven unhappy years the kingship is held by the half-Fomorian Bres before Nuada's physician Dian Cécht fashions for him a silver arm, and he is restored. War with the Fomorians breaks out and a decisive battle is fought: the Second Battle of Moytura. Nuada falls to Balor of the Evil Eye, but Balor's grandson, Lugh of the Long Arm, kills him and becomes king. The Tuatha Dé Danann enjoy one hundred and fifty years of unbroken rule.

Milesians

The story of the Gaels, which was interrupted at the end of Book 2, is now resumed. Íth, who has spied Ireland from the top of Breogán's Tower, journeys to Ireland to investigate his discovery. There he is welcomed by the rulers, but jealous nobles kill him and his men return to Iberia with his body. The Milesians, or sons of his uncle Míl Espáine, set out to avenge his death and conquer the island. When they arrive in Ireland, they advance to Tara, the royal seat, to demand the kingship. On the way they are greeted in turn by three women, Banba, Fodla and Ériu, who are the queens of the three co-regents of the land. Each woman welcomes the Milesians and tells them that her name is the name by which the land is known, and asks that it remain so if the Milesians are victorious in battle. One of the Milesians, the poet Amergin, promises that it shall be so. At Tara they are greeted by the three kings of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who defend their claim to the joint kingship of the land. It is decided that the Milesians must return to their ships and sail out to sea to a distance of nine waves from the shore, so that the Tuatha Dé Danann may have a chance to mobilise their forces. But when the Milesians are "beyond nine waves", the druids of the Tuatha Dé Danann conjure up a ferocious storm. The Milesian fleet is driven out to sea but Amergin dispels the wind with his poetry. Of the surviving ships those of Éber land at Inber Scéine (the Shannon estuary) in the west of the country, while those of Érimón land at Inber Colptha (the mouth of the Boyne). In two ensuing battles at Sliabh Mis and Tailtiu, the Tuatha Dé Danann are defeated. They are eventually driven out and the lordship of Ireland is divided between Éber and Éremón.

Roll of the pagan kings of Ireland

Modelled on the Biblical Books of Kings, this book recounts the deeds of various kings of Ireland, most of them legendary or semi-legendary, from the time of Éber and Érimón to the early 5th century of the Christian era.

Roll of the Christian kings of Ireland

A continuation of the previous book. This book is the most accurate part of LGE, being concerned with historical kings of Ireland whose deeds and dates are preserved in contemporary written records.

O'Rahilly's interpretation

The manner in which Celtic-speaking peoples came to be in possession of the island of Ireland is still a matter of conjecture. However, four separate invasions or migrations were distinguished by the Celtic scholar T. F. O'Rahilly (see O'Rahilly's historical model; the dates given below are highly doubtful):

- Pretanic - Between about 700 and 500 BC P-Celtic-speaking people colonised Britain and Ireland from the continent. There is no real evidence of an organised military invasion, but by the 6th century ancient Greek geographers knew these islands as "the Pretanic Isles". In Britain they were absorbed by later invaders, except in the extreme north, where they were known to the Romans as Picti, or "painted peoples." In Ireland their descendants — wherever they managed to preserve some measure of cultural, if not political, independence — were known as the Cruthin, a Gaelic or Q-Celtic form of Priteni, which is believed to be their original name for themselves. The name "Britain" is thought to be derived from Priteni.

- Bolgic or Ernean - The Builg or Érainn were various names of another P-Celtic-speaking people who invaded Ireland around 500 BC. They might be linked with the continental Belgae, and of the same stock as the Britons. According to their own traditions, they came to Ireland via Britain. In Irish pseudohistory they appear as the Fir Bolg, a name which was variously interpreted as meaning "men of bags" (Latin viri bulgarum) or "belly men", though "men of the thunderbolt" would probably be more accurate.

- Laginian - Around 300 BC three closely related tribes arrived in Ireland, known as the Laigin, the Domnainn and the Gálioin. They are speculated to have been P-Celtic-speaking tribes from Armorica (Brittany). In Ireland they conquered the southeastern quarter of the country — which became known as Laighean, or Leinster, after them — and the west (Connacht). The Érainn, however, would have remained in control of the north and south. This is perhaps how Ireland first came to be divided into four provinces. Some of these tribes also settled in Britain (possibly from Ireland). In the southwest the Domnainn (Latin: Dumnonii) gave their name to Devon, while in the northwest they founded Dumbarton and the Kingdom of Strathclyde.

- Goidelic or Gaelic - Around 100 BC a Q-Celtic-speaking people invaded Ireland, traditionally said to be people from north-western Iberia where Gallaecian was spoken although O'Rahilly favoured Aquitania, in southwest Gaul. They arrived in two separate contingents: the Connachta, who landed at the mouth of the Boyne and carved out a fifth province for themselves (later known as Meath) around Tara between Ulster and Leinster; and the Eoganachta, who insinuated themselves into Munster and gradually became the dominant force in the south of the country. Goidel — or Gael — may have originated as a P-Celtic name that the native population gave to these invaders, but in any event they themselves adopted the name.

So how is this reconstruction of the history reflected in LGE? To begin with, if the Cruthin had an invasion myth, no trace of it remains in LGE, which supports the belief that their colonisation of the country was a lengthy process of gradual migration. And the first two "takings" of Ireland — those of Cessair and Partholón — seem to be wholly fanciful, with no direct historical value at all.

The next taking, however, that of the Nemedians, may well have been a mythologised version of the historical Bolgic invasion of the 5th or 6th century BC. This belief is supported by many details in the text of LGE, a discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article.

The next two takings would also seem to have a historical basis. We can identify the Fir Bolg and their allies with the Érainn again, invading the country for a second time because their ancestors the Nemedians were portrayed as having abandoned the country (which the historical Érainn probably never did). The Tuatha Dé Danann might be a wholly mythical people who have been substituted for the historical Lagin, Domnainn and Gálioin. It has been suggested that this confused state of affairs arose because the Laginian invasion was not a true taking, since the Laginians only conquered about half the country. Nevertheless, the First Battle of Moytura probably does reflect an historical victory of the Lagin over the Érainn in County Sligo (the location of two townlands known as West and East Moytirra), by virtue of which the Lagin conquered the western province. The Second Battle of Moytura, however, would then have been entirely fictional, as most likely were the Fomorians.

The Milesian invasion is clearly a semi-legendary version of the historical Goidelic invasion. Éber and Éremón (whose names mean simply "Irishman" and "Ireland", respectively) have replaced the historical leaders of the Eoganachta and Connachta respectively. In the case of Éber, the allusion may be to Iberia, an ancient name for the Iberian Peninsula, whence doubtless warriors of Celtiberian stock originated and emigrated to Ireland. The name of their father Míl Espáne is similarly derived from the Latin Miles Hispaniae, "a soldier of Hispania."[92] O'Rahilly, however, believed that the Goidelic invaders of Ireland came from south-western Gaul and not Iberia. See O'Rahilly (1946) for further discussion.

The Roll of the Kings before the Introduction of Christianity contains much that is of interest to historians, but a lot of it is confused and bowdlerised. For example, the story of Túathal Techtmar, who is depicted as a High King of Ireland in the early 2nd century of the Christian era, is thought to be another version of the Goidelic invasion, Túathal Techtmar being in reality the historical antecedent of Éremón. Éber's real antecedent, Mug Nuadat, would then be similarly displaced. There are also doublets of the Bolgic and Laginian invasions in the stories of two other kings, Lugaid mac Dáire and Labraid Loingsech. These bowdlerisations may have been politically motivated: by providing the pre-Gaelic peoples of the island with pedigrees going back to Míl, the Gaels hoped to deny them any prior claim to the country, and so justify the Gaelic conquest.

As mentioned earlier, The Roll of the Kings after the Introduction of Christianity is the most accurate part of LGE. For the most part, these kings are familiar to us from other sources. It should also be pointed out that whereas the first eight books of LGE are usually regarded as part of the Early Mythological Cycle, the last two books are properly assigned to the Historical Cycle.

See also

- Leabhar na nGenealach

- James Ware (historian)

- The Book of Invasions - a rock concept album by Horslips

Sources

Edition

- Lebor Gabála Érenn, original text edited and translated by R A Stewart Macalister, D. Litt

- Part I: Irish Texts Society, Volume 34, London 1938, reprinted 1993. ISBN 1-870166-34-5.

- Part II: Irish Texts Society, Volume 35, London 1939. ISBN 1-870166-35-3.

- Part III: Irish Texts Society, Volume 39, London 1940. ISBN 1-870166-39-6.

- Part IV: Irish Texts Society, Volume 41, London 1941. ISBN 1-870166-41-8.

- Part V: Irish Texts Society, Volume 44, London 1956. ISBN 1-870166-44-2.

References

- O'Rahilly, T.F. Early Irish History and Mythology. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1946.

- Scowcroft, R.M. "Leabhar Gabhála Part I: The growth of the text’, Ériu 36 (1987). 79–140.

- Scowcroft, R.M. "Leabhar Gabhála Part II: The growth of the tradition." Ériu 39 (1988). 1–66.

Further reading

- Carey, John. "Lebor Gabála and the Legendary History of Ireland." In Medieval Celtic Literature and Society, ed. Helen Fulton. Dublin: Four Courts, 2005. pp. 32–48.

- Carey, John. A new introduction to Lebor Gabála Érenn. The Book of the taking of Ireland, edited and translated by R.A. Stewart Macalister. Dublin: Irish Texts Society, 1993.

- Carey, John. The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory. Quiggin Pamphlets on the Sources of Mediaeval Gaelic History. 1994.

- Ó Buachalla, Liam. "The Lebor Gabala or book of invasions of Ireland." Journal of the Cork Historical & Archaeological Society 67 (1962): 70-9.

- Ó Concheanainn, Tomás. "Lebor Gabála in the Book of Lecan." In A Miracle of Learning. Studies in Manuscripts and Irish Learning. Essays in Honour of William O'Sullivan, ed. Toby Barnard et al. Aldershot and Bookfield: Ashgate, 1998. 40-51.

External links

- Online Index to the Lebor Gabála Érenn (Book of Invasions) based on R.A.S. Macalister's translations and notes, CELT.

- Lebor Gabála Érenn, Books 1-8, Mary Jones' Celtic Literature Collective.

- Book of Invasions, Timeless Myths.

- Irish genes, Breakingnews.i.e.

- Myths of British ancestry, Prospect magazine.

- A brief overview and large genealogical chart of Mythological Cycle narratives in the LGE are hosted at Jones' Celtic Encyclopedia.

| Part of a series on |

| Celtic mythology |

|---|

|

| Gaelic mythology |

| Brythonic mythology |

| Religious vocations |

| Festivals |

The Mythological Cycle [93][94] is a somewhat outdated coined term[95] still used to refer collectively to an ancient literary tradition that concerns the godlike peoples who allegedly arrived in five migratory invasions into Ireland and principally recounts the doings of the Tuatha Dé Danann.[96]

It comprises one of the four major cycles of early Irish literary tradition, the others being the Ulster cycle, the Fenian Cycle and the Cycle of the Kings.[97]

The topic is also surveyed under Irish mythology, Mythological cycle. A list of literature belonging to the cycle is given below.

Overview

The characters appearing in the cycle are essentially gods from the pre-Christian pagan past in Ireland. Commentators exercising caution, however, qualify them as representing only "godlike" beings, and not gods. This is because the Christian scribes who composed the writings were generally (though not always) careful not to refer to the Tuatha Dé Danann and other beings explicitly as deities. The disguises are thinly veiled nonetheless, and these writings contain discernable vestiges of early Irish polytheistic cosmology (World view).[98]

Examples of works from the cycle include numerous prose tales, verse texts, as well as pseudo-historical chronicles (primarily the Lebor Gabála Érenn (LGE), commonly called The Book of Invasions) found in medieval vellum manuscripts or later copies. Some of the romances are of later composition and found only in paper manuscripts dating to near-modern times (Cath Maige Tuired and The Fate of the Children of Tuireann).

Near-modern histories such as the Annals of the Four Masters and Geoffrey Keating's History of Ireland (=Seathrún Céitinn, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn) are also sometimes considered viable sources, since they may offer additional insights with their annotated and interpolated reworkings of LGE accounts.

Orally transmitted folk-tales may also be, in a broad sense, considered mythological cycle material, notably, the folk-tales that describe Cian's tryst with Balor's daughter while attempting to recover the bountiful cow Glas Gaibhnenn.