자궁경부암: 두 판 사이의 차이

잔글 봇: 틀 이름 및 스타일 정리 |

편집 요약 없음 |

||

| 100번째 줄: | 100번째 줄: | ||

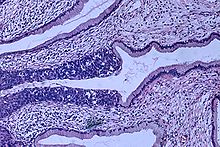

파일:Histopathology_of_squamous_cell_carcinoma_of_the_cervix.png|침습성 편평상피세포암은 문합하는 세포 둥지 또는 단일 세포의 침윤이 특징적이다.<ref>{{웹 인용|url=https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cervixscc.html|title=Squamous cell carcinoma and variants|work=Pathology Outlines|vauthors=Turashvili G}}</ref> 이 사진은 분화도가 낮은 저분자암이다. H&E 염색 |

파일:Histopathology_of_squamous_cell_carcinoma_of_the_cervix.png|침습성 편평상피세포암은 문합하는 세포 둥지 또는 단일 세포의 침윤이 특징적이다.<ref>{{웹 인용|url=https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cervixscc.html|title=Squamous cell carcinoma and variants|work=Pathology Outlines|vauthors=Turashvili G}}</ref> 이 사진은 분화도가 낮은 저분자암이다. H&E 염색 |

||

파일:Cervix_quadrants_and_directions.svg|자궁경부암의 위치는 사분면으로 설명할 수 있으며, [[:en:Lithotomy|쇄석위]] 자세에서 시계방향으로도 표현할 수 있다. |

파일:Cervix_quadrants_and_directions.svg|자궁경부암의 위치는 사분면으로 설명할 수 있으며, [[:en:Lithotomy|쇄석위]] 자세에서 시계방향으로도 표현할 수 있다. |

||

</gallery>비록 편평상피세포암이 자궁경부암 중 가장 높은 발병률을 가지고 있지만, 최근 수십년간 샘암종의 발생률이 증가하고 있다.<ref name="Robbins4">{{서적 인용|title=Robbins Basic Pathology|year=2007|edition=8th|publisher=Saunders Elsevier|pages=718–721|isbn=978-1-4160-2973-1|vauthors=Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN}}</ref> 자궁경관내막선암은 자궁경부암의 조직학 유형중 20-25%를 차지한다. |

</gallery>비록 편평상피세포암이 자궁경부암 중 가장 높은 발병률을 가지고 있지만, 최근 수십년간 샘암종의 발생률이 증가하고 있다.<ref name="Robbins4">{{서적 인용|title=Robbins Basic Pathology|year=2007|edition=8th|publisher=Saunders Elsevier|pages=718–721|isbn=978-1-4160-2973-1|vauthors=Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN}}</ref> 자궁경관내막선암은 자궁경부암의 조직학 유형중 20-25%를 차지한다. 위형(Gastric-type) 점액성 선암은 공격적인 성향을 보이는 아주 드문 유형의 암이다. 이 종류의 악성종양은 고위험 인간 유두종바이러스 (HPV)와 관련되어 있지 않다.<ref>{{저널 인용|title=A rare case of gastric-type mucinous endocervical adenocarcinoma in a 59-year-old woman|journal=Przeglad Menopauzalny = Menopause Review|date=September 2020|volume=19|issue=3|pages=147–150|doi=10.5114/pm.2020.99563|pmc=7573334|pmid=33100952|vauthors=Mulita F, Iliopoulos F, Kehagias I}}</ref> 자궁경부에서 드물게 발생할 수 있는 비암성 악성종양으로는 [[흑색종]]과 [[림프종]]이 있다. [[:en:International_Federation_of_Gynecology_and_Obstetrics|International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics]] (FIGO) 병기는 다른 대부분의 암의 [[TNM 분류|TNM 병기]]와는 달리 [[림프절]] 침범을 다루지 않는다. 수술을 한 경우, 병리학자들로부터 얻은 정보를 이용하여 별도의 병리 병기를 설정할 수 있지만, 원래의 임상적 병기를 대체하지는 않는다. {{출처|date=September 2020}} |

||

=== 병기 결정 (Staging) === |

=== 병기 결정 (Staging) === |

||

| 119번째 줄: | 119번째 줄: | ||

=== 선별검사 === |

=== 선별검사 === |

||

[[파일:Cervical_screening_Test_Vehicle_in_Minsheng_Community_20120421.jpg|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cervical_screening_Test_Vehicle_in_Minsheng_Community_20120421.jpg|섬네일|대만의 자궁경부암 선별검사 차량 ]] |

[[파일:Cervical_screening_Test_Vehicle_in_Minsheng_Community_20120421.jpg|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cervical_screening_Test_Vehicle_in_Minsheng_Community_20120421.jpg|섬네일|대만의 자궁경부암 선별검사 차량 ]] |

||

[[파일:VIANeg.gif|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:VIANeg.gif|섬네일| |

[[파일:VIANeg.gif|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:VIANeg.gif|섬네일|아세트산을 도포한 후 자궁경부 시진- 음성]] |

||

[[파일:VIAPosCIN1.gif|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:VIAPosCIN1.gif|섬네일| |

[[파일:VIAPosCIN1.gif|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:VIAPosCIN1.gif|섬네일|아세트산을 도포한 후 자궁경부 시진 -양성, CIN1]] |

||

{{본문|Cervical screening|Pap test}} |

{{본문|Cervical screening|Pap test}} |

||

| 147번째 줄: | 147번째 줄: | ||

=== 영양 === |

=== 영양 === |

||

비타민 A , 비타민 B12, 비타민 C, 비타민 E 그리고 베타카로틴은 발병 위험도를 낮추는 것과 관련이 있다.<ref>{{저널 인용|title=Vitamin A and risk of cervical cancer: a meta-analysis|journal=Gynecologic Oncology|date=February 2012|volume=124|issue=2|pages=366–373|doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.012|pmid=22005522|vauthors=Zhang X, Dai B, Zhang B, Wang Z}}</ref><ref>{{저널 인용|title=Vitamin or antioxidant intake (or serum level) and risk of cervical neoplasm: a meta-analysis|journal=BJOG|date=October 2011|volume=118|issue=11|pages=1285–1291|doi=10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03032.x|pmid=21749626|vauthors=Myung SK, Ju W, Kim SC, Kim H|hdl-access=free|s2cid=38761694|hdl=2027.42/86903}}</ref> |

비타민 A , 비타민 B12, 비타민 C, 비타민 E 그리고 베타카로틴은 발병 위험도를 낮추는 것과 관련이 있다.<ref>{{저널 인용|title=Vitamin A and risk of cervical cancer: a meta-analysis|journal=Gynecologic Oncology|date=February 2012|volume=124|issue=2|pages=366–373|doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.012|pmid=22005522|vauthors=Zhang X, Dai B, Zhang B, Wang Z}}</ref><ref>{{저널 인용|title=Vitamin or antioxidant intake (or serum level) and risk of cervical neoplasm: a meta-analysis|journal=BJOG|date=October 2011|volume=118|issue=11|pages=1285–1291|doi=10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03032.x|pmid=21749626|vauthors=Myung SK, Ju W, Kim SC, Kim H|hdl-access=free|s2cid=38761694|hdl=2027.42/86903}}</ref> |

||

== 치료 == |

|||

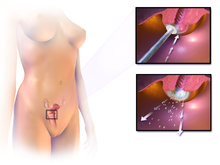

[[File:Cervical_Cryotherapy.png|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cervical_Cryotherapy.png|섬네일|자궁경부 냉동요법]] |

|||

근치적 골반 수술에 능숙한 외과의사에 대한 접근이나 선진국에서의 생싱 능력 유지 요법의 등장으로 인해 자궁경부암에 대한 치료는 전세계적으로 다양하다. 초기 자궁경부암의 경우 일반적으로 환자가 원하면 생신능력을 유지할수 있는 치료 방법이 있다.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/treating/by-stage.html|title=Cervical Cancer Treatment Options {{!}} Treatment Choices by Stage|website=www.cancer.org|access-date=12 September 2020}}</ref> 자궁경부암이 방사선에 민감하기 때문에, 방사선 치료는 수술을 하지 못하는 모든 병기에서 사용된다. 수술적 치료가 방사선 치료보다 더 나은 결과를 가지고는 한다.<ref name="BaalbergenVeenstra2013">{{cite journal|title=Primary surgery versus primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy for early adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=January 2013|volume=2021|issue=1|pages=CD006248|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006248.pub3|pmc=7387233|pmid=23440805|vauthors=Baalbergen A, Veenstra Y, Stalpers L}}</ref> 또한 항암화학요법이 사용될수 있고, 방사선 단독으로 치료하는 것보다 더 효과적으로 알려져있다.<ref>{{cite journal|title=A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in cervical cancer (cervix uteri)|journal=Acta Oncologica|date=2003|volume=42|issue=5–6|pages=546–556|doi=10.1080/02841860310014660|pmid=14596512|vauthors=Einhorn N, Tropé C, Ridderheim M, Boman K, Sorbe B, Cavallin-Ståhl E|doi-access=free}}</ref> 방사선 단독 치료와 비교하였을 때, 동시 항암 화학 방사선 치료를 시행 했을 경우 전체 생존율을 증가시키고 병의 재발 위험을 감소시키는 것으로 나타났다. <ref>{{cite journal|title=Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: individual patient data meta-analysis|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|author1=Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration (CCCMAC)|date=January 2010|volume=2010|issue=1|pages=CD008285|doi=10.1002/14651858.cd008285|pmc=7105912|pmid=20091664}}</ref> '패스트 트랙 수술' 또는 '상향된 회복 프로그램'과 같은 수술 전후의 처치 방법이 수술로 인한 스트레스를 낮추고 부인과적 종양 수술이후의 회복을 돕는다는 것에 대한 증거는 낮은 신뢰도을 가진다. <ref>{{cite journal|title=Perioperative enhanced recovery programmes for women with gynaecological cancers|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=March 2022|volume=2022|issue=3|pages=CD008239|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008239.pub5|pmc=8922407|pmid=35289396|vauthors=Chau JP, Liu X, Lo SH, Chien WT, Hui SK, Choi KC, Zhao J}}</ref> |

|||

미세침윤성 암 (stage IA) 은 [[:en:Hysterectomy|자궁절제술]]([[:en:Vagina|질]]을 포함한 자궁 전체를 제거하는 것)을 통해 치료할 수 있다.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Microinvasive carcinoma of the cervix|journal=American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology|date=April 1983|volume=145|issue=8|pages=981–991|doi=10.1016/0002-9378(83)90852-9|pmid=6837683|vauthors=van Nagell JR, Greenwell N, Powell DF, Donaldson ES, Hanson MB, Gay EC}}</ref> stage IA2일 경우에는 [[:en:Lymph_node|림프절]] 또한 제거되어야 한다. 국소 수술인 [[:en:Loop_electrical_excision_procedure|고리 전기 절제술 (LEEP)]] <!--(LEEP)--> 또는 [[:en:Cervical_conization|원추 절제술]]이 대안이 될 수 있다.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/cancer/cervical-cancer/cone-biopsy-conization-for-abnormal-cervical-cell-changes|title=Cone biopsy (conization) for abnormal cervical cell changes|date=12 January 2007|website=[[WebMD]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071119114319/http://www.webmd.com/cancer/cervical-cancer/cone-biopsy-conization-for-abnormal-cervical-cell-changes|archive-date=19 November 2007|url-status=live|access-date=2 December 2007|vauthors=Erstad S}}</ref><ref name="LinZhou2017">{{cite journal|title=Vaginectomy and vaginoplasty for isolated vaginal recurrence 8 years after cervical cancer radical hysterectomy: A case report and literature review|journal=The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research|date=September 2017|volume=43|issue=9|pages=1493–1497|doi=10.1111/jog.13375|pmid=28691384|vauthors=Lin Y, Zhou J, Dai L, Cheng Y, Wang J|s2cid=42161609}}</ref> 체계적 검토에 따르,면 stage IA2 자궁경부암을 가진 여성에서 다양한 수술 기법을 결정하기 위한 더 많은 증거가 필요하다고 결론내렸다.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Surgical treatment of stage IA2 cervical cancer|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=May 2014|volume=2018|issue=5|pages=CD010870|doi=10.1002/14651858.cd010870.pub2|pmc=6513277|pmid=24874726|vauthors=Kokka F, Bryant A, Brockbank E, Jeyarajah A}}</ref> |

|||

원추 절제술에서 깨끗한 절제면<ref name="pmid8244170">{{cite journal|title=Early invasive carcinoma of the cervix|journal=Gynecologic Oncology|date=October 1993|volume=51|issue=1|pages=26–32|doi=10.1006/gyno.1993.1241|pmid=8244170|vauthors=Jones WB, Mercer GO, Lewis JL, Rubin SC, Hoskins WJ}}</ref> (조직 생검에서 종양이 암이 아닌 조직으로 둘러싸여 있다는 결과가 나오는 경우, 즉 종양이 완전히 제거되었다는 것이다.) 을 얻지 못한 경우, 생식 능력을 보존하고자 하는 여성에서 선택할 수 있는 치료 방법은 [[:en:Trachelectomy|자궁경부절제술]]이다.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.baymoon.com/~gyncancer/library/glossary/bldeftrachelect.htm|title=Trachelectomy|year=2001|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927143641/http://www.baymoon.com/~gyncancer/library/glossary/bldeftrachelect.htm|archive-date=27 September 2007|url-status=dead|access-date=2 December 2007|vauthors=Dolson L}}</ref> 난소와 자궁을 보전하면서 수술적으로 암을 제거하려는 시도는 자궁절제술보다 더 보수적인 수술을 하게 한다. 이는 주변으로 확산하지 않은 stage I 자궁경부암에서의 바람직한 선택지이지만 이에 숙련된 의사가 적기 때문에 아직 표준치료로 간주되지는 않는다. <ref name="pmid16493253">{{cite journal|title=Radical trachelectomy with laparoscopic lymphadenectomy: review of oncologic and obstetrical outcomes|journal=Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology|date=February 2006|volume=18|issue=1|pages=8–13|doi=10.1097/01.gco.0000192968.75190.dc|pmid=16493253|vauthors=Burnett AF|s2cid=22958941}}</ref> 암이 얼마나 주변으로 확산되었는지 알 수 없기 때문에 가장 경험이 풍부한 외과의사 조차 수술 현미경 검사 이후까지 자궁경부절제술을 시행하는 것을 장담하지 못한다. 만약 수술방에서 환자가 전신마취가 되어 있을 때 외과의사가 현미경적으로 절제면이 깨끗하다고 확신을 하지 못하는 경우, 자궁절제술이 필요하게 된다. 물론 이는 환자가 수술 전 동의한 경우에만 수술 중에 수술 방법을 변경할 수 있다. stage 1B와 몇몇 stage 1A 암에서 림프절에 확산이 되었을 가능성이 있기 때문에 외과의사는 병리학적 평가를 위해 자궁 주변 림프절 절제를 하게 된다.{{citation needed|date=September 2017}} |

|||

근치자궁절제술은 복부<ref name="pmid15918265">{{cite journal|title=[Abdominal radical trachelectomy--technique and experience]|journal=Ceska Gynekologie|date=March 2005|volume=70|issue=2|pages=117–122|language=cs|pmid=15918265|vauthors=Cibula D, Ungár L, Svárovský J, Zivný J, Freitag P}}</ref> 또는 질<ref name="pmid15936061">{{cite journal|title=Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early-stage cervical cancer. A series of 50 pregnancies and review of the literature|journal=Gynecologic Oncology|date=July 2005|volume=98|issue=1|pages=3–10|doi=10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.014|pmid=15936061|vauthors=Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, Roy M}}</ref> 을 통해서 이루어질 수 있고, 어느것이 더 나은지에 대해서는 의견이 분분하다.<ref name="pmid8812529">{{cite journal|title=Vaginal radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer|journal=Gynecologic Oncology|date=September 1996|volume=62|issue=3|pages=336–339|doi=10.1006/gyno.1996.0245|pmid=8812529|vauthors=Roy M, Plante M, Renaud MC, Têtu B}}</ref> 림프절 절제를 포함한 복부 근치 자궁경부절제술은 2~3일의 입원기간이 요구되며 대부분의 여성들이 약 6주 정도의 빠른 회복기간을 가진다. 합병증은 흔하지 않지만 수술후 임신한 여성의 경우 조산이나 후기 유산의 가능성이 높다.<ref name="pmid10760765">{{cite journal|title=Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a treatment to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients|journal=Cancer|date=April 2000|volume=88|issue=8|pages=1877–1882|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000415)88:8<1877::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-W|pmid=10760765|vauthors=Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P|doi-access=free}}</ref> 수술후 임신을 시도하기 전 적어도 1년정도 기다리는 것이 권장된다.<ref name="pmid12548192">{{cite journal|title=Radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with uterine preservation in the treatment of cervical cancer|journal=American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology|date=January 2003|volume=188|issue=1|pages=29–34|doi=10.1067/mob.2003.124|pmid=12548192|vauthors=Schlaerth JB, Spirtos NM, Schlaerth AC}}</ref> 자궁경부절제술로 깨끗하게 암이 제거된 경우 남은 경부에서의 재발은 드물다.<ref name="pmid16493253" /> 그럼에도 불구하고 적극적으로 임신을 시도하기 전까지 안전한 성생활을 통해 HPV에 대한 노출을 줄이는 것 뿐만 아니라, 재발을 모니터링 할 필요가 있어 잔존한 하부 자궁부분의 생검, 자궁경부암에 대한 민감한 예방, 자궁경부 세포진 검사 및 질확대경 검사를 포함한 추적관찰이 권장된다. |

|||

Early stages (IB1 and IIA less than 4 cm) can be treated with radical hysterectomy with removal of the lymph nodes or [[:en:Radiation_therapy|radiation therapy]]. Radiation therapy is given as external beam radiotherapy to the pelvis and [[:en:Brachytherapy|brachytherapy]] (internal radiation). Women treated with surgery who have high-risk features found on pathologic examination are given radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy to reduce the risk of relapse.{{citation needed|date=September 2017}} A Cochrane review has found moderate-certainty evidence that radiation decreases the risk of disease progression in people with stage IB cervical cancer, when compared to no further treatment.<ref name="Rogers_2012">{{cite journal|title=Radiotherapy and chemoradiation after surgery for early cervical cancer|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=May 2012|volume=5|issue=5|pages=CD007583|doi=10.1002/14651858.cd007583.pub3|pmc=4171000|pmid=22592722|vauthors=Rogers L, Siu SS, Luesley D, Bryant A, Dickinson HO}}</ref> However, little evidence was found on its effects on overall survival.<ref name="Rogers_2012" /> |

|||

[[File:Diagram_showing_the_position_of_the_applicators_for_internal_radiotherapy_for_cervical_cancer_CRUK_344.svg|링크=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diagram_showing_the_position_of_the_applicators_for_internal_radiotherapy_for_cervical_cancer_CRUK_344.svg|오른쪽|섬네일|Brachytherapy for cervical cancer]] |

|||

Larger early-stage tumors (IB2 and IIA more than 4 cm) may be treated with radiation therapy and [[:en:Cisplatin|cisplatin]]-based chemotherapy, hysterectomy (which then usually requires [[:en:Adjuvant|adjuvant]] radiation therapy), or cisplatin chemotherapy followed by hysterectomy. When cisplatin is present, it is thought to be the most active single agent in periodic diseases.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Cervical cancer|journal=Lancet|date=June 2003|volume=361|issue=9376|pages=2217–2225|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13778-6|pmid=12842378|vauthors=Waggoner SE|s2cid=24115541}}</ref> Such addition of platinum-based chemotherapy to chemoradiation seems not only to improve survival but also reduces risk of recurrence in women with early stage cervical cancer (IA2–IIA).<ref>{{cite journal|title=Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy for early stage cervical cancer|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=November 2016|volume=11|issue=11|pages=CD005342|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD005342.pub4|pmc=4164460|pmid=27873308|vauthors=Falcetta FS, Medeiros LR, Edelweiss MI, Pohlmann PR, Stein AT, Rosa DD}}</ref> A Cochrane review found a lack of evidence on the benefits and harms of primary hysterectomy compared to primary chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer in stage IB2.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Type II or type III radical hysterectomy compared to chemoradiotherapy as a primary intervention for stage IB2 cervical cancer|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=October 2018|volume=2018|issue=10|pages=CD011478|doi=10.1002/14651858.cd011478.pub2|pmc=6516889|pmid=30311942|vauthors=Nama V, Angelopoulos G, Twigg J, Murdoch JB, Bailey J, Lawrie TA}}</ref> |

|||

Advanced-stage tumors (IIB-IVA) are treated with radiation therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy. On 15 June 2006, the US [[:en:Food_and_Drug_Administration|Food and Drug Administration]] approved the use of a combination of two chemotherapy drugs, [[:en:Hycamtin|hycamtin]] and cisplatin, for women with late-stage (IVB) cervical cancer treatment.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01391.html|title=FDA Approves First Drug Treatment for Late-Stage Cervical Cancer|date=15 June 2006|publisher=[[Food and Drug Administration|U.S. Food and Drug Administration]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071010035641/https://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01391.html|archive-date=10 October 2007|url-status=live|access-date=2 December 2007}}</ref> Combination treatment has significant risk of [[:en:Neutropenia|neutropenia]], [[:en:Anemia|anemia]], and [[:en:Thrombocytopenia|thrombocytopenia]] side effects.<ref>{{cite journal|title=The combination of cisplatin and topotecan as a second-line treatment for patients with advanced/recurrent uterine cervix cancer|journal=Medicine|date=April 2018|volume=97|issue=14|pages=e0340|doi=10.1097/MD.0000000000010340|pmc=5902288|pmid=29620661|vauthors=Moon JY, Song IC, Ko YB, Lee HJ}}</ref> |

|||

There is insufficient evidence whether anticancer drugs after standard care help women with locally advanced cervical cancer to live longer.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Adjuvant chemotherapy after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=December 2014|volume=2019|issue=12|pages=CD010401|doi=10.1002/14651858.cd010401.pub2|pmc=6402532|pmid=25470408|vauthors=Tangjitgamol S, Katanyoo K, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, Manusirivithaya S, Supawattanabodee B}}</ref> |

|||

For surgery to be curative, the entire cancer must be removed with no cancer found at the margins of the removed tissue on examination under a microscope.<ref name="Sar2015">{{cite journal|title=Curative pelvic exenteration for recurrent cervical carcinoma in the era of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A systematic review|journal=European Journal of Surgical Oncology|url=https://hal-univ-rennes1.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01147372/file/Curative%20Pelvic%20Exenteration%20For%20Recurrent%20Cervical.pdf|date=August 2015|volume=41|issue=8|pages=975–985|doi=10.1016/j.ejso.2015.03.235|pmid=25922209|vauthors=Sardain H, Lavoue V, Redpath M, Bertheuil N, Foucher F, Levêque J|s2cid=21911045}}</ref> This procedure is known as exenteration.<ref name="Sar2015" /> |

|||

No evidence is available to suggest that any form of follow‐up approach is better or worse in terms of prolonging survival, improving quality of life or guiding the management of problems that can arise because of the treatment and that in the case of radiotherapy treatment worsen with time.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Follow-up protocols for women with cervical cancer after primary treatment|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=November 2013|volume=2014|issue=11|pages=CD008767|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008767.pub2|pmc=8969617|pmid=24277645|vauthors=Lanceley A, Fiander A, McCormack M, Bryant A|collaboration=Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro-oncology and Orphan Cancer Group}}</ref> A 2019 review found no controlled trials regarding the efficacy and safety of interventions for vaginal bleeding in women with advanced cervical cancer.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Palliative interventions for controlling vaginal bleeding in advanced cervical cancer|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|date=March 2019|volume=3|issue=3|pages=CD011000|doi=10.1002/14651858.cd011000.pub3|pmc=6423555|pmid=30888060|vauthors=Eleje GU, Eke AC, Igberase GO, Igwegbe AO, Eleje LI}}</ref> |

|||

[[:en:Tisotumab_vedotin|Tisotumab vedotin]] (Tivdak) was approved for medical use in the United States in September 2021.<ref name="Tivdak FDA label">{{Cite web|url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761208s000lbl.pdf|title=Enforcement Reports}}</ref><ref name="Seagen PR">{{cite web|url=https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210920005921/en/|title=Seagen and Genmab Announce FDA Accelerated Approval for Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin-tftv) in Previously Treated Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical Cancer|date=20 September 2021|publisher=Seagen|access-date=20 September 2021|via=Business Wire}}</ref><gallery> |

|||

File:Diagram_showing_the_area_removed_with_a_posterior_exenteration_for_cancer_of_the_cervix_CRUK_288.svg|Diagram showing the area removed with a posterior surgery |

|||

File:Diagram_showing_the_area_removed_with_a_total_exenteration_operation_for_cancer_of_the_cervix_CRUK_289.svg|Diagram showing the area removed with a total operation |

|||

File:Diagram_showing_the_area_removed_with_an_anterior_exenteration_operation_for_cancer_of_the_cervix_CRUK_290.svg|Diagram showing the area removed with an anterior operation |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Prognosis == |

|||

== HPV 백신의 부작용사례 == |

== HPV 백신의 부작용사례 == |

||

2023년 9월 1일 (금) 23:57 판

| |

|---|---|

| |

| 진료과 | 종양학 |

| 증상 | 조기: 없음[1] 후기: 질출혈, 골반통, 성교통[1] |

| 통상적 발병 시기 | 10~20년 후[2] |

| 유형 | 편평상피세포암, 선암, 기타[3] |

| 병인 | 인유두종 바이러스 (HPV)[4][5],인간 면역 결핍 바이러스, 헤르페스 바이러스 등 바이러스 감염, 흡연, 이른 성경험, 성병 감염, 장기간 경구피임약 사용, 많은 출산 경험 등 |

| 위험 인자 | 흡연, 면역결핍, 경구피임약, 어린나이에 성관계, 많은 성관계 파트너[1][3][6] |

| 진단 방식 | 자궁경부세포진검사 원추 절제 생체 검사, 자기공명영상 검사, 방광경 검사[1] |

| 예방 | 정기적 자궁경부암 선별검사, 인유두종 바이러스 (HPV) 백신, 성관계시 콘돔사용[7][8] |

| 치료 | 수술, 화학 요법, 방사선치료, 면역항암요법[1] |

| 예후 | 5년생존률: 68% 미국 46% (인도)[9] |

| 빈도 | 604,127 new cases (2020)[10] |

| 사망 | 341,831 (2020)[10] |

자궁경부암(子宮頸部癌, Cervical cancer)은 자궁목(자궁경부)에서 발생하는 암이다.[1] 체내의 다른 부위로 침범하거나 전이될 수 있는 비정상 세포에 의해 발생한다.[11] 일반적으로 초기에는 증상이 발현하지 않지만,[1] 후기 증상으로는 비정상적인 질출혈, 골반통 또는 성교통이 발생할 수 있다.[1] 성관계후 발생하는 출혈은 심각한 경우가 아닐 수 있지만, 자궁경부암의 존재를 나타내는 지표가 되기도 한다.[12]

원인 및 진단

인유두종 바이러스 감염 (HPV)이 자궁경부암 발생의 90% 이상을 차지하는 원인이다.[4][5] 그러나 인유두종 바이러스 감염자의 대부분이 자궁경부암에 걸린다는 것은 아니다.[2][13] HPV 16과 18 균주가 고등급 전암병변 원인의 약 50%를 차지한다.[14] 다른 위험 요소로는 흡연, 면역결핍, 경구피임약, 첫 성관계 시기가 이른 경우, 많은 성관계 파트너를 갖는 경우가 있지만, 상대적으로 중요하지 않다.[1][3] 유전적 요인 또한 자궁경부암의 위험을 증가시킨다.[15] 자궁경부암은 일반적으로 10~20년간의 전암성 변화를 거쳐 발생한다.[2] 자궁경부암 중 약 90%는 편평상피세포암, 10%는 선암, 그리고 소수의 경우가 다른 유형들이다.[3] 일반적으로 자궁경부암은 자궁경 검진과 조직 생검을 통해 진단된다.[1] 영상 검사는 암이 전이가 되었는지를 확인하는 데에 쓰인다.[1]

예방 및 선별검사

인유두종 바이러스 (HPV) 백신을 통해 바이러스군의 2가지~7가지의 고위험 균주를 예방할 수 있고, 자궁 경부암의 최대 90%를 예방할 수 있다.[8][16][17] 발암에 대한 위험이 존재하기 때문에, 가이드라인에 따르면 정기적인 자궁경부세포진검사 (Pap smear)가 권고된다.[8] 우리나라의 경우에는 만 20세 이상 여성인 경우 2년에 1회 자궁경부세포진검사를 하는것이 국가건강검진으로 지정되어 있다[18]. 다른 예방 방법으로는 성관계 파트너를 적게 또는 아예 갖지 않는 것이나, 콘돔을 사용하는 것이 있다.[7] 자궁경부세포진검사 (Pap smear) 또는 아세트산 (VIA) 을 이용한 자궁경부암 선별검사는 전암병변을 확인할 수 있고, 치료를 통해 암으로 변하는 것을 예방할 수 있다.[19] 치료방법으로는 수술, 항암치료, 방사선 치료를 적절히 조합하여 적용한다.[1] 자궁경부암의 미국 5년 생존률 은 68%이다.[20] 치료에 대한 결과는 얼마나 빠르게 암이 발견되었는지에 매우 의존한다.[3]

역학

전 세계적으로, 자궁경부암은 부인과암 중에서 4번째로 흔한 암이자 4번째로 흔한 암으로 인한 사망원인이다. 2012년에는 약 528,000건의 자궁경부암이 발생했고 266,000명이 사망했다.[2] 이는 암으로 인한 전체 사망건의 약 8%를 차지한다.[21] 자궁경부암의 약 70%의 발생과, 90%의 사망이 개발도상국에서 발생한다.[2][22] 저소득 국가에서는 여성 10만명당 유병률이 47.3으로 암 사망의 가장 흔한 원인 중 하나이다.[23][19] 선진국에서는 선별검사 프로그램을 도입하여 자궁경부암 발생률을 현저히 감소시켰다.[24] (특히 저소득 국가에서) 자궁경부암으로 인한 전세계 사망률 감소에 대한 예상 시나리오는 WHO에서 정의한 3중 개입 전략을 통해 권장된 예방 목표의 달성에 관한 가정을 고려하여 검토되었다.[25] 의학연구에서, HeLa로 알려진 가장 유명한 불사화 세포주는 Henrietta Lacks라는 여성의 자궁 경부 세포로 만들어 졌다.[26]

징후 및 증상

자궁경부암의 초기단계에서는 증상이 없을 수 있다.[27][28] 질출혈, 접촉 출혈 (가장 흔한 형태로는 성관계 후 출혈), 또는 (드물게) 질 내 종괴가 악성 종양의 존재를 가리킬 수 있다. 성관계중 나타나는 중등도의 통증과 질 분비물 또한 자궁경부암의 증상 일 수 있다.[29] 진행암의 경우, 복부, 폐, 기타부위에 전이될 수 있다.[30]

진행된 자궁경부암의 증상에는: 식욕부진, 체중감소, 피로, 골반통, 허리통증, 다리 통증, 다리 부종, 심한 질 출혈, 골절, (드물게) 질을 통한 소변 또는 대변의 누출 이 포함 될 수 있다.[31] 질세척(douching) 또는 골반 내진 후에 발생하는 출혈은 자궁경부암의 흔한 증상 중 하나이다.

원인

몇몇 종류의 인유두종 바이러스 감염이 자궁경부암의 가장 큰 위험 요인이고, 흡연이 두번째 요인이다.[32] 인간면역결핍바이러스 (HIV) 감염 또한 위험요인이다.[32] 자궁경부암의 모든 원인이 밝혀지지는 않았지만, 몇가지의 요소들이 연관되어 있다.[33][34]

인유두종 바이러스

인유두종 바이러스 (HPV) 16번과 18번은 전세계 자궁경부암의 원인 중 75%를 차지한다. 31번과 45번은 10%를 차지한다.[35]

여러 명의 성 파트너를 가지거나, 성별에 관계없이 여러 명의 성 파트너를 가진 파트너가 있는 여성은 더 높은 자궁경부암 가능성을 가진다.[36][37]

150-200 종류의 인유두종 바이러스 (HPV) 중,[38][39] 15개가 고위험군으로 분류되고 (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82), 3개는 잠재적 고위험군 (26, 53, and 66), 12개는 저위험군으로 분류된다. (6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, and CP6108).[40]

상피의 양성 종양의 일종인 생식기 사마귀 역시 여러 종류의 HPV에 의해 발생할 수 있다. 그러나 사마귀를 일으키는 혈청형은 대개 자궁경부

암과는 연관되어있지 않다. 동시에 여러 종류의 HPV에 감염되는 것이 흔하여, 자궁경부암을 일으키는 종류와 사마귀를 일으키는 종류에 동시에 감염되어 있는 경우도 많다. 한편 자궁경부암이 발생하려면 HPV 감염이 선행해야 한다는 것이 일반적으로 통용되는 사실이다.[41]

흡연

직접 흡연이든 간접 흡연이든, 흡연은 자궁경부암 확률을 높인다. 인유두종 바이러스(HPV)에 감염된 여성중, 현재 혹은 과거 흡연자는 침습성 암에대한 발병률이 대략 2~3배 높다. 간접흡연 또한 더 낮은 수준이지만 발병확률을 높이는 것과 관련있다.[42]

흡연은 또한 자궁경부암의 진행과 관련 있다.[43][44][45] 흡연은 여러가지 방법으로 여성의 위험도를 높이는데, 자궁경부암을 직,간접적으로 유발할 수 있다.[43][45][46] 직접적으로 발암을 유발하는 방법은 자궁경부암으로 진행할 가능성이 있는 자궁목상피내종양 (CIN3)의 발생확률을 높이는 것이다.[43] CIN3 병변이 암으로 진행될 때에 대부분 인유두종 바이러스가 기여하지만, 항상 그런것은 아니므로 자궁경부암과 직접적인 연관이 있다고 말할 수 있다.[46] 흡연량이 많거나 오랜 기간 흡연을 해왔을 경우 아닌 경우보다 CIN3 병변이 생길 위험도가 더 높아진다.[47] 흡연은 자궁경부암에 직접적으로 영향을 주는 것과 동시에, HPV의 발달에도 도움을 주고, 간접적으로 발암의 원인이 된다.[45] 이미 HPV 양성인 여성의 경우, 자궁경부암 발병 확률이 더 높아진다.[47]

경구 피임약

장기간의 경구 피임약 사용은 HPV 감염 여성에서 자궁경부암 발병률을 높이는 것과 관련있다. 5~9년간 경구 피임약을 복용해온 여성의 경우 침습성 암의 유발율이 3배정도 높고, 10년간 복용해온 사람은 약 4배정도 위험하다.[48]

많은 임신 경험

임신경험이 많은 것은 자궁경부암 위험을 높이는 것과 관련있다. HPV 감염 여성에서, 7번 이상 만기 임신을 한 여성은 미분만부에 비해 약 4배의 위험도를 가지고, 한번 또는 두번의 만기 임신을 한 여성에 비해 약 3배의 위험도를 가진다.[48]

진단

생검

자궁경부 세포진검사 (Pap smear)는 선별 검사로 사용될 수 있지만, 최대 50%에서 거짓 음성 이 발생한다.[49][50] 다른 우려사항은 자궁경부 세포진검사의 비용으로, 세계의 많은 영역에서 감당하기 어렵다.[51]

자궁경부암 또는 전암병변을 확진하기 위해서는 자궁경부의 생검이 필요하다. 생검은 때때로 질확대경을 이용한다. 희석된 아세트산 용액을 이용하여 자궁경부 표면의 비정상세포를 강조하고, 루골용액으로 정상세포를 갈색으로 염색하여 대비를 준 뒤, 질확대경을 통해 확대하여 눈으로 직접 확인 후 생검한다.[52][53]

자궁경부 생검에 사용되는 의료기기는 펀치 포셉을 포함한다. 질확대경 시진을 바탕으로 추정한 질병의 심각도는 진단의 한 부분을 차지한다. 이후 진단 및 치료 방법은 병리학적 검사를 위해 자궁경부 내부 조직을 채취하는 과정인 고리 전기 절제술 (LEEP) 과 자궁경부원추절제술이다. 이 절차는 생검에서 고도의 자궁목상피내종양 (CIN)으로 확진이되었을때 시행한다.

생검전에, 증상에 대한 다른 원인을 배제하기위해 의사가 영상검사를 제안하기도 한다. 초음파, CT, MRI와 같은 영상 진단장비는 감별질환, 암의 확산, 인접 구조에 대한 영향을 찾기 위해 사용된다. 일반적으로 자궁경부암은 자궁목에 비균질 종양으로 보입니다.[54]

검사 중 음악을 재생하거나 모니터로 검사과정을 보여주는 등의 개입은 검사와 관련된 불안감을 줄일 수 있습니다.[55]

전암 병변

자궁경부암의 잠재력을 가진 자궁목상피내종양 (CIN)은 병리학자에 의한 자궁목 생검을 통해 진단된다. 전암성 이형성 변화에 있어서 자궁목상피내종양 병기가 사용된다.

자궁경부암 전암병변의 이름 및 조직학적 분류는 20세기 동안 변화되어 왔다. 세계보건기구 분류 체계[56][57] 에서는 경증, 중등증, 중증 이형성 , 자궁 상피내 암종 (CIS)으로 명명하고 설명한다. 자궁목상피내종양 (CIN) 이라는 용어는 이러한 병변의 비정상성에 관한 스펙트럼을 강조하고, 치료의 표준화를 위해 개발되었다.[57] 경증의 이형성을 CIN1, 중등도의 이형성을 CIN2, 중증의 이형성 및 CIS를 CIN3로 분류한다. 최근에는 CIN2 와 CIN3 가 CIN2/3로 병합되었다. 병리학자들은 조직검사를 통해 이러한 결과를 보고한다.

자궁경부세포진 검사 (Pap smear) 결과에 대한 베데스다 시스템 용어와 혼동되어서는 안된다. 베데스다 결과에 포함된 것은 다음과 같다 : 저등급편평상피내병터 (LSIL),고등급편평상피내병터 (HSIL). LSIL은 CIN1에 해당할 수 있고, HSIL은 CIN2 과 CIN3에 해당 할 수 있지만[57] 서로 다른 검사 결과이며 자궁경부세포진 검사 결과가 조직학적 소견과 반드시 일치하지는 않는다.

암의 아형

침습적 자궁경부암의 조직학적 아형은 다음을 포함한다.:[58][59]

-

침습성 편평상피세포암은 문합하는 세포 둥지 또는 단일 세포의 침윤이 특징적이다.[63] 이 사진은 분화도가 낮은 저분자암이다. H&E 염색

-

자궁경부암의 위치는 사분면으로 설명할 수 있으며, 쇄석위 자세에서 시계방향으로도 표현할 수 있다.

비록 편평상피세포암이 자궁경부암 중 가장 높은 발병률을 가지고 있지만, 최근 수십년간 샘암종의 발생률이 증가하고 있다.[64] 자궁경관내막선암은 자궁경부암의 조직학 유형중 20-25%를 차지한다. 위형(Gastric-type) 점액성 선암은 공격적인 성향을 보이는 아주 드문 유형의 암이다. 이 종류의 악성종양은 고위험 인간 유두종바이러스 (HPV)와 관련되어 있지 않다.[65] 자궁경부에서 드물게 발생할 수 있는 비암성 악성종양으로는 흑색종과 림프종이 있다. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 병기는 다른 대부분의 암의 TNM 병기와는 달리 림프절 침범을 다루지 않는다. 수술을 한 경우, 병리학자들로부터 얻은 정보를 이용하여 별도의 병리 병기를 설정할 수 있지만, 원래의 임상적 병기를 대체하지는 않는다. [출처 필요]

병기 결정 (Staging)

자궁경부암은 수술 결과가 아닌 임상 검사를 바탕으로 FIGO 시스템을 따라 병기가 결정된다. 2018년 FIGO 병기 분류 개정 이전에는 다음과 같은 진단 검사만이 병기를 결정하는 데에 사용할 수 있었다 : 촉진, 시진, 질확대경 검사, 자궁목긁어냄술, 자궁경 검사, 방광경 검사, 직장경검사, 정맥 요로조영술, 폐와 골격계의 X-ray 촬영, 자궁경부 원추절제술. 그러나 현재 시스템에서는 병기 결정시에 영상검사 또는 병리학적 검사를 사용할 수 있다.[66]

-

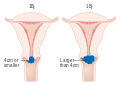

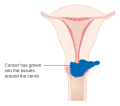

Stage 1A 자궁경부암

-

Stage 1B 자궁경부암

-

Stage 2A 자궁경부암

-

Stage 2B 자궁경부암

-

Stage 3B 자궁경부암

-

Stage 4A 자궁경부암

-

Stage 4B 자궁경부암

예방

선별검사

자궁경부세포진검사 (Pap test)를 통해 자궁목 세포를 확인하는 것은 자궁경부암의 발병 건수와 사망률을 현저히 줄였다.[67] 액상 세포 검사는 불충분한 검체의 수를 줄일 수 있다.[68][69][70] 매 3~5년마다 자궁경부세포진검사 (Pap test)와 적절한 후속 조치를 하는것은 자궁경부암 발생을 80% 까지 줄일 수 있다.[71] 비정상 결과로는 전암병변의 존재가 있을 수 있고 , 이 경우 자궁확대경 검사를 통해 진단하고 예방적으로 치료해야한다. 저등급 병변의 치료는 이후 부작용으로 생식능력과 임신에 영향 줄 수 있다.[72]

여성들이 선별검사를 받도록 권장하는 개인적인 초청은 검사를 받을 확률을 높인다. 교육 자료 도한 여성들이 선별검사를 받을 확률을 높이지만, 개인적인 초청만큼 효과적이지는 않다.[73]

2010 유럽 가이드라인에 따르면 선별검사를 시작하는 나이는 20세에서 30세 사이지만, 가능하면 25세 또는 30세 이전이 좋으며, 인구내 질병 부담과 이용 가능한 자원에 따라 다르다.[71]

미국에서는 성관계를 언제 시작했는지 등의 위험 요소와는 관계 없이 21세에 선별검사를 시작하는것이 권고된다.[74] 자궁 경부 세포진검사는 21세에서 65세 사이에 3년마다 시행 해야 한다.[74] 65세 이상의 여성은 이전 10년간의 선별검사에서 비정상으로 나온 결과가 없는 경우, 그리고 CIN2 이상의 병변이 없었던 경우 선별검사를 중단 할 수 있다.[74][75][76] HPV 백신 접종 상태는 검사 비율에 영향을 주지 않는다.[75]

30세에서 65세 사이 여성은 여러가지 권장되는 검사방법이 있다.[77] 3년마다 자궁경부 세포진 검사, 5년마다 HPV 검사, 5년마다 자궁경부 세포진 검사와 HPV 검사를 동시에 하는 것이다.[77][75] Screening is not beneficial before age 25, as the rate of disease is low. 유병률이 낮기 때문에 25세 이하의 여성에서는 선별검사가 비용적으로 효율적이지 않다. 60세 이상의 여성에서도 과거 부정적인 소견이 없었다면 마찬가지이다.[72] 미국 임상 종양학회 가이드라인은 이용가능한 자원의 수준에 따라 다른 수준의 권장사항을 제공하고 있다.[78]

개발도상국에서는 자궁경부세포진 검사가 그리 효과적이지 않다[79] 이는 많은 곳이 의료 인프라가 열악하고, 검사를 하고 해석하는 능숙하고 훈련된 전문의들이 부족하며, 추적관찰을 하지 않는 정보가 부족한 여성들이 많고, 결과를 얻기까지 긴 시간이 걸리기 때문이다.[79] 아세트산을 이용한 시진과 HPV DNA 검사가 시도되었지만, 애매한 성공을 거두었다.[79]

차단 피임법

성관계 중 차단 피임법 (콘돔, 질격막, 자궁경부 캡) 또는 살정효과가 있는 젤을 이용하는것은 감염 확률을 줄일 수 있지만 완전히 위험하지 않은 것은 아니다.[80] 콘돔을 사용하는 것은 생식기 사마귀를 예방할 수 있고[81] , HIV와 클라미디아와 같은 자궁경부암을 유발할 수 있는 위험요소인 다른 성 매개 감염으로부터 보호할 수 있다.

백신 접종

세가지의 HPV 백신 (가다실, 가다실9, 서바릭스)은 자궁경부와 회음부의 암 및 전암병변 위험률을 각각 93%, 62% 가량 줄인다.[82] 백신은 적어도 8년간 HPV 16번과 18번에 대해 92%에서 100%의 예방효과를 가진다.[80]

HPV 백신은 일반적으로 바이러스 감염이 발생하기 전인 9세~26세 사이에 접종된다. 백신의 효과가 지속되는 기간과 부스터샷이 필요한지에 대한 것은 알려져 있지 않다. The high cost of this vaccine has been a cause for concern. 우려가 되는 부분은 백신의 높은 비용이다. 몇몇 국가에서는 HPV 백신을 지원하기 위한 프로그램을 고려하고 있거나, 이미 시행중이다. 미국 임상 종양학회는 이용가능한 자원의 수준에 따라 가이드라인을 구성했다.[83]

Since 2010, young women in Japan have been eligible to receive the cervical cancer vaccination for free. 2010년부터 일본의 젊은 여성들은 무료로 자궁경부암 예방접종을 받을 수 있다.[84] 2013년 6월, 일본 보건복지부인 후생노동성은 백신을 투여하기 전에 , 의료기관은 접종대상자에게 보건복지부에서는 백신을 권장하지 않는다는 것을 알려야 한다고 명령했다.[84] 하지만 여전히 예방접종을 원하는 일본 여성에게 백신은 무료로 제공된다.[84]

영양

비타민 A , 비타민 B12, 비타민 C, 비타민 E 그리고 베타카로틴은 발병 위험도를 낮추는 것과 관련이 있다.[85][86]

치료

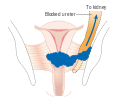

근치적 골반 수술에 능숙한 외과의사에 대한 접근이나 선진국에서의 생싱 능력 유지 요법의 등장으로 인해 자궁경부암에 대한 치료는 전세계적으로 다양하다. 초기 자궁경부암의 경우 일반적으로 환자가 원하면 생신능력을 유지할수 있는 치료 방법이 있다.[87] 자궁경부암이 방사선에 민감하기 때문에, 방사선 치료는 수술을 하지 못하는 모든 병기에서 사용된다. 수술적 치료가 방사선 치료보다 더 나은 결과를 가지고는 한다.[88] 또한 항암화학요법이 사용될수 있고, 방사선 단독으로 치료하는 것보다 더 효과적으로 알려져있다.[89] 방사선 단독 치료와 비교하였을 때, 동시 항암 화학 방사선 치료를 시행 했을 경우 전체 생존율을 증가시키고 병의 재발 위험을 감소시키는 것으로 나타났다. [90] '패스트 트랙 수술' 또는 '상향된 회복 프로그램'과 같은 수술 전후의 처치 방법이 수술로 인한 스트레스를 낮추고 부인과적 종양 수술이후의 회복을 돕는다는 것에 대한 증거는 낮은 신뢰도을 가진다. [91]

미세침윤성 암 (stage IA) 은 자궁절제술(질을 포함한 자궁 전체를 제거하는 것)을 통해 치료할 수 있다.[92] stage IA2일 경우에는 림프절 또한 제거되어야 한다. 국소 수술인 고리 전기 절제술 (LEEP) 또는 원추 절제술이 대안이 될 수 있다.[93][94] 체계적 검토에 따르,면 stage IA2 자궁경부암을 가진 여성에서 다양한 수술 기법을 결정하기 위한 더 많은 증거가 필요하다고 결론내렸다.[95]

원추 절제술에서 깨끗한 절제면[96] (조직 생검에서 종양이 암이 아닌 조직으로 둘러싸여 있다는 결과가 나오는 경우, 즉 종양이 완전히 제거되었다는 것이다.) 을 얻지 못한 경우, 생식 능력을 보존하고자 하는 여성에서 선택할 수 있는 치료 방법은 자궁경부절제술이다.[97] 난소와 자궁을 보전하면서 수술적으로 암을 제거하려는 시도는 자궁절제술보다 더 보수적인 수술을 하게 한다. 이는 주변으로 확산하지 않은 stage I 자궁경부암에서의 바람직한 선택지이지만 이에 숙련된 의사가 적기 때문에 아직 표준치료로 간주되지는 않는다. [98] 암이 얼마나 주변으로 확산되었는지 알 수 없기 때문에 가장 경험이 풍부한 외과의사 조차 수술 현미경 검사 이후까지 자궁경부절제술을 시행하는 것을 장담하지 못한다. 만약 수술방에서 환자가 전신마취가 되어 있을 때 외과의사가 현미경적으로 절제면이 깨끗하다고 확신을 하지 못하는 경우, 자궁절제술이 필요하게 된다. 물론 이는 환자가 수술 전 동의한 경우에만 수술 중에 수술 방법을 변경할 수 있다. stage 1B와 몇몇 stage 1A 암에서 림프절에 확산이 되었을 가능성이 있기 때문에 외과의사는 병리학적 평가를 위해 자궁 주변 림프절 절제를 하게 된다.[출처 필요]

근치자궁절제술은 복부[99] 또는 질[100] 을 통해서 이루어질 수 있고, 어느것이 더 나은지에 대해서는 의견이 분분하다.[101] 림프절 절제를 포함한 복부 근치 자궁경부절제술은 2~3일의 입원기간이 요구되며 대부분의 여성들이 약 6주 정도의 빠른 회복기간을 가진다. 합병증은 흔하지 않지만 수술후 임신한 여성의 경우 조산이나 후기 유산의 가능성이 높다.[102] 수술후 임신을 시도하기 전 적어도 1년정도 기다리는 것이 권장된다.[103] 자궁경부절제술로 깨끗하게 암이 제거된 경우 남은 경부에서의 재발은 드물다.[98] 그럼에도 불구하고 적극적으로 임신을 시도하기 전까지 안전한 성생활을 통해 HPV에 대한 노출을 줄이는 것 뿐만 아니라, 재발을 모니터링 할 필요가 있어 잔존한 하부 자궁부분의 생검, 자궁경부암에 대한 민감한 예방, 자궁경부 세포진 검사 및 질확대경 검사를 포함한 추적관찰이 권장된다.

Early stages (IB1 and IIA less than 4 cm) can be treated with radical hysterectomy with removal of the lymph nodes or radiation therapy. Radiation therapy is given as external beam radiotherapy to the pelvis and brachytherapy (internal radiation). Women treated with surgery who have high-risk features found on pathologic examination are given radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy to reduce the risk of relapse.[출처 필요] A Cochrane review has found moderate-certainty evidence that radiation decreases the risk of disease progression in people with stage IB cervical cancer, when compared to no further treatment.[104] However, little evidence was found on its effects on overall survival.[104]

Larger early-stage tumors (IB2 and IIA more than 4 cm) may be treated with radiation therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy, hysterectomy (which then usually requires adjuvant radiation therapy), or cisplatin chemotherapy followed by hysterectomy. When cisplatin is present, it is thought to be the most active single agent in periodic diseases.[105] Such addition of platinum-based chemotherapy to chemoradiation seems not only to improve survival but also reduces risk of recurrence in women with early stage cervical cancer (IA2–IIA).[106] A Cochrane review found a lack of evidence on the benefits and harms of primary hysterectomy compared to primary chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer in stage IB2.[107]

Advanced-stage tumors (IIB-IVA) are treated with radiation therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy. On 15 June 2006, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a combination of two chemotherapy drugs, hycamtin and cisplatin, for women with late-stage (IVB) cervical cancer treatment.[108] Combination treatment has significant risk of neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia side effects.[109]

There is insufficient evidence whether anticancer drugs after standard care help women with locally advanced cervical cancer to live longer.[110]

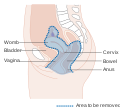

For surgery to be curative, the entire cancer must be removed with no cancer found at the margins of the removed tissue on examination under a microscope.[111] This procedure is known as exenteration.[111]

No evidence is available to suggest that any form of follow‐up approach is better or worse in terms of prolonging survival, improving quality of life or guiding the management of problems that can arise because of the treatment and that in the case of radiotherapy treatment worsen with time.[112] A 2019 review found no controlled trials regarding the efficacy and safety of interventions for vaginal bleeding in women with advanced cervical cancer.[113]

Tisotumab vedotin (Tivdak) was approved for medical use in the United States in September 2021.[114][115]

-

Diagram showing the area removed with a posterior surgery

-

Diagram showing the area removed with a total operation

-

Diagram showing the area removed with an anterior operation

Prognosis

HPV 백신의 부작용사례

2016년 4월 17일: 영국 북서부 그레이터 맨체스터(Greater Manchester)주의 13살의 쉐즐 자만(Shazel Zaman) 사망. HPV 백신을 맞은 뒤 4일 후 사망하였다. 아직 부검중.[116]

미국의 의료전문매체 ‘백신임팩트’는 6월 7일, 백신으로 인한 피해여성 34명의 사례를 보도.[116]

- 뉴질랜드, 12살 소녀 앰버 스미스, 엄마의 증언에 따르면 HPV 백신을 맞은 뒤, 온 몸에 통증을 느껴 잘 걷지도 못하는 상태가 되었다고 함.

- 미국, 매디와 올리비아 자매, “HPV 백신을 맞고 나서 임신할 수 없는 불구의 몸이 됐다”고 증언

- 펜실베니아의 27세 소녀 케이티 로빈슨, 11살 때 처음 HPV 백신을 맞고, 피로와 두통, 복통, 메스꺼움, 관절통, 기억 상실증, 현기증, 피부 질환 등에 시달렸다.

한국의 사례

식약처는 “우리나라에서도 일시마비, 운동장애 등 14건(2013년 기준)의 부작용 사례가 보고됐다”고 발표했다.[116]

2020년 8월 기준 사람유두종바이러스 감염증 백신 국가예방접종 도입 후 약 150만 건 접종 후 113건(0.007%)의 이상반응이 신고되었다.[117] 이 중 심인성 반응인 일시적인 실신 및 실신 전 어지러움 등의 증상(59건, 52.2%)이 가장 많았다.[117]

| 총계 | 국소 | 전신이상반응 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 실신 | 실신전증상 | 알레르기 및

피부이상반응 |

발열, 두통,

오심, 구토 등 (비특이적 전신반응) |

신경계 및

근골격계a) |

기타b) | ||

| 113 | 12 | 42 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 8 |

- a) 신경계 및 근골격계: 편두통, 안면신경마비, 하지 통증, 접종 중 양팔떨림, 실신 중 경련 등(대부분 증상 지속없이 소실됨)

- b) 기타: 염좌, 탈모, 설사 등

- ※ 신고 된 이상반응 사례들은 의료진 또는 보호자가 신고한 자료로 예방접종과의 인과성이 증명되지 않았다.[117] 또한 증상이 경미하여 신고하지 않은 사례들은 포함되지 않아, 실제 이상반응 발생률과 차이가 있을 수 있다.[117]

일본의 사례[116]

일본은 2013년 4월부터 HPV 백신을 '필수 정기 접종'으로 의무적으로 지정되어, 만 12세 이상의 여성 청소년들에게 무상으로 맞게 했다. 2014년 11월까지 338만명의 초·중·고교생들이 HPV 백신을 맞았다. 두달 만인 2013년 6월부터 “이 백신을 맞은 13~16세 소녀들에게 만성 통증증후군인 ‘CRPS(복합부위통증증후군)’ 등의 이상 반응이 발생했다”는 보고가 잇따랐다. 주사를 맞은 338만명 중 2584명이 부작용을 호소, 이 가운데 186명은 증상이 나아지지 않은 것으로 파악됐다. 그러자 일본 후생노동성은 2013년 6월 ‘HPV 백신 필수 접종 정책’을 철회했다.

HPV 백신과 만성피로증후군[116]

일본 센다이사회보험 병원의 오사무 호타 박사는 “만성피로증후군(CFS)을 호소하는 환자 가운데 상당수가 HPV 백신을 맞은 여성이었다”면서 그 관찰 결과를 2016년 4월 독일에서 열린 국제 백신 심포지움에서 발표했다.

호타 박사는 2014년 10월~2015년 9월까지 약 1년 동안 HPV 백신을 맞은 여성 중 이상증세를 보이는 41명을 관찰하였다.

환자들은 아래 증상들을 호소했다고 한다.

- 수면장애

- 두통

- 피로

- 어지럼증

- 광선혐기증(빛을 보면 눈에 이상이 나타나는 증상)

- 관절 통증

박사는 “41명 중 34명(82%)은 이같은 증상 때문에 학교에도 가지 못했다”고 했다.

호타 박사는 이에 대해 “인후염이 심할 때 나타나는 증상”이라고 설명했다. 인후염은 미국 질병관리예방본부(CDC)와 일본 후생성이 만성피로증후군(CFS)을 유발하는 질환 중 하나로 꼽고 있는 질병이다.

호타 박사는 “인후염은 면역체계 손상이란 측면에서 살펴봐야 한다”고 강조했다.

박사의 연설을 주최한 "아동 의료안전 연구기관(CMSRI)"은 홈페이지를 통해 “백신은 면역체계를 자극해 신경 장애를 일으키며, 이는 만성피로증후군(CFS)의 원인이 될 가능성이 높다”고 발표했다.

이 부분에 대해서 WHO(세계보건기구)는 일본이 작은 증거를 바탕으로 정책을 결정해서 안전하고 효과적인 백신의 사용을 줄이게 만들었다. 그것이 진짜 위험을 나을 수 있을 것이라고 경고하였다.

HPV 해외 부작용에 대한 전문단체의 입장

HPV 예방접종 때문에 걷지 못하게 되었다는데?

일본에서는 HPV 백신 8백만 건 이상이 공급되었으며, 복합부위통증증후군(case of complex regional pain syndrome, CRPS) 5사례가 보고되었다.[117]

그러나 2014년 일본 후생노동성의 조사결과 전형적인 복합부위통증증후군에 부합하지 않았으며, 백신과의 관련성은 인정하기 힘들고, 접종대상자의 심리적 불안과 긴장에 의한 것으로 잠정결론 내렸다.[117]

또한 2016년 4월 소아과학회, 산부인과학회 등 17개 단체로 이루어진 일본의 예방접종추진 전문협의회는 HPV 예방접종을 적극 권장하는 입장을 밝혔다.[117]

또한 일본 내에서 HPV 예방접종에 대해 공포를 키운 논문(실험쥐에 HPV 백신을 접종 한 후 신경학적 손상을 보이는 결과를 보여줌)이 동물연구의 실험조건을 부풀린 것으로 밝혀져 해당 학회지는 논문 게재를 철회한다⁑(Scientific Reports, ’18.5월)고 밝혔다.[117]

⁑(철회사유) 고농도의 HPV백신과 백일해 독소를 함께 주입함으로써 뇌-신경계에 대한 영향을 최대화 하도록 디자인되어 있으며, 백일해 독소를 함께 주입하는 것은 HPV 백신 자체로 인한 신경학적 손상을 보려고 한 연구의 목적에 부합하지 않음[117]

유럽의약청(EMA) 역시 ’16년 초 HPV 백신과 복합부위통증증후군의 관련성이 없다고 공식 발표하였다.(’16.1.12.)[117][118]

HPV 예방접종 때문에 임신할 수 없게 되었다는데?

미국질병관리본부(CDC)는 난소부전 증상이 HPV 백신과 관련성이 없으며, 오히려 자궁경부암에 걸렸을 경우 치료 과정에서 임신이 어렵게 될 위험을 백신접종을 통한 암 예방으로 줄일 수 있다고 밝히고 있다.[117]

각주

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 아 자 차 카 타 “Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)”. 《NCI》. 2014년 3월 14일. 2014년 7월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 24일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 《World Cancer Report 2014》. World Health Organization. 2014. Chapter 5.12쪽. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 “Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)”. 《National Cancer Institute》. 2014년 3월 14일. 2014년 7월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). 《Robbins Basic Pathology》 8판. Saunders Elsevier. 718–721쪽. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ 가 나 Kufe D (2009). 《Holland-Frei cancer medicine》 8판. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 1299쪽. ISBN 9781607950141. 2015년 12월 1일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S (2007). “The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer”. 《Disease Markers》 23 (4): 213–227. doi:10.1155/2007/914823. PMC 3850867. PMID 17627057.

- ↑ 가 나 “Cervical Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)”. 《National Cancer Institute》. 2014년 2월 27일. 2014년 7월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 “Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines”. 《National Cancer Institute》. 2011년 12월 29일. 2014년 7월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Global Cancer Facts & Figures 3rd Edition” (PDF). 2015. 9쪽. 2017년 8월 22일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 8월 29일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (May 2021). “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries”. 《CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians》 71 (3): 209–249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. PMID 33538338. S2CID 231804598.

- ↑ “Defining Cancer”. 《National Cancer Institute》. 2007년 9월 17일. 2014년 6월 25일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ Tarney CM, Han J (2014). “Postcoital bleeding: a review on etiology, diagnosis, and management”. 《Obstetrics and Gynecology International》 2014: 192087. doi:10.1155/2014/192087. PMC 4086375. PMID 25045355.

- ↑ Dunne EF, Park IU (December 2013). “HPV and HPV-associated diseases”. 《Infectious Disease Clinics of North America》 27 (4): 765–778. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2013.09.001. PMID 24275269.

- ↑ “Cervical cancer”. 《www.who.int》 (영어). 2022년 5월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ramachandran D, Dörk T (October 2021). “Genomic Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer”. 《Cancers》 13 (20): 5137. doi:10.3390/cancers13205137. PMC 8533931. PMID 34680286.

- ↑ “FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV”. 《U.S. Food and Drug Administration》. 2014년 12월 10일. 2015년 1월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2015년 3월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Tran NP, Hung CF, Roden R, Wu TC (2014). 〈Control of HPV Infection and Related Cancer Through Vaccination〉. 《Viruses and Human Cancer》. Recent Results in Cancer Research 193. 149–171쪽. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38965-8_9. ISBN 978-3-642-38964-1. PMID 24008298.

- ↑ 한국건강관리협회. “한국건강관리협회>국가건강검진>암검진”. 《한국건강관리협회》.

- ↑ 가 나 World Health Organization (February 2014). “Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer”. 2014년 2월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 24일에 확인함.

- ↑ “SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Cervix Uteri Cancer”. 《NCI》. National Cancer Institute. 2014년 11월 10일. 2014년 7월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 6월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ 《World Cancer Report 2014》. World Health Organization. 2014. Chapter 1.1쪽. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ “Cervical cancer prevention and control saves lives in the Republic of Korea”. 《World Health Organization》. 2018년 11월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ Donnez, Jacques (2020년 4월 1일). “An update on uterine cervix pathologies related to infertility”. 《Fertility and Sterility》 113 (4): 683–684. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.02.107. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 32228872.

- ↑ Canavan TP, Doshi NR (March 2000). “Cervical cancer”. 《American Family Physician》 61 (5): 1369–1376. PMID 10735343. 2005년 2월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M, Keane A, Simms KT, Caruana M, 외. (February 2020). “Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries”. 《Lancet》 395 (10224): 591–603. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30157-4. PMC 7043006. PMID 32007142.

- ↑ Carraher Jr CE (2014). 《Carraher's polymer chemistry》 9판. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. 385쪽. ISBN 9781466552036. 2015년 10월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). 《Robbins Basic Pathology》 8판. Saunders Elsevier. 718–721쪽. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ Canavan TP, Doshi NR (March 2000). “Cervical cancer”. 《American Family Physician》 61 (5): 1369–1376. PMID 10735343. 2005년 2월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Cervical Cancer Symptoms, Signs, Causes, Stages & Treatment”. 《medicinenet.com》.

- ↑ Li H, Wu X, Cheng X (July 2016). “Advances in diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer”. 《Journal of Gynecologic Oncology》 27 (4): e43. doi:10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e43. PMC 4864519. PMID 27171673.

- ↑ Nanda R (2006년 6월 9일). 〈Cervical cancer〉. 《MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia》. National Institutes of Health. 2007년 10월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Gadducci A, Barsotti C, Cosio S, Domenici L, Riccardo Genazzani A (August 2011). “Smoking habit, immune suppression, oral contraceptive use, and hormone replacement therapy use and cervical carcinogenesis: a review of the literature”. 《Gynecological Endocrinology》 27 (8): 597–604. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.558953. PMID 21438669. S2CID 25447563.

- ↑ Campbell S, Monga A (2006). 《Gynaecology by Ten Teachers》 18판. Hodder Education. ISBN 978-0-340-81662-2.

- ↑ “Cervical Cancer Symptoms, Signs, Causes, Stages & Treatment”. 《medicinenet.com》.

- ↑ Dillman RK, Oldham RO, 편집. (2009). 《Principles of cancer biotherapy》 5판. Dordrecht: Springer. 149쪽. ISBN 9789048122899. 2015년 10월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “What Causes Cancer of the Cervix?”. American Cancer Society. 2006년 11월 30일. 2007년 10월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, Kuypers JM, Stine K (June 2001). “Papanicolaou test screening and prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among women who have sex with women”. 《American Journal of Public Health》 91 (6): 947–952. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.947. PMC 1446473. PMID 11392939.

- ↑ “HPV Type-Detect”. Medical Diagnostic Laboratories. 2007년 10월 30일. 2007년 9월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gottlieb N (2002년 4월 24일). “A Primer on HPV”. 《Benchmarks》. National Cancer Institute. 2007년 10월 26일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, 외. (February 2003). “Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer”. 《The New England Journal of Medicine》 348 (6): 518–527. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641. hdl:2445/122831. PMID 12571259. S2CID 1451343.

- ↑ Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, Heideman DA, Meijer CJ (January 2006). “HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis: concepts and clinical implications”. 《The Journal of Pathology》 208 (2): 152–164. doi:10.1002/path.1866. PMID 16362994. S2CID 25400770.

- ↑ “Cervical Cancer Prevention”. 《PDQ》. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. 2022년 12월 26일.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Luhn P, Walker J, Schiffman M, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, Gold MA, 외. (February 2013). “The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer”. 《Gynecologic Oncology》 128 (2): 265–270. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.003. PMC 4627848. PMID 23146688.

- ↑ Remschmidt C, Kaufmann AM, Hagemann I, Vartazarova E, Wichmann O, Deleré Y (March 2013). “Risk factors for cervical human papillomavirus infection and high-grade intraepithelial lesion in women aged 20 to 31 years in Germany”. 《International Journal of Gynecological Cancer》 23 (3): 519–526. doi:10.1097/IGC.0b013e318285a4b2. PMID 23360813. S2CID 205679729.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Gadducci A, Barsotti C, Cosio S, Domenici L, Riccardo Genazzani A (August 2011). “Smoking habit, immune suppression, oral contraceptive use, and hormone replacement therapy use and cervical carcinogenesis: a review of the literature”. 《Gynecological Endocrinology》 27 (8): 597–604. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.558953. PMID 21438669. S2CID 25447563.

- ↑ 가 나 Agorastos T, Miliaras D, Lambropoulos AF, Chrisafi S, Kotsis A, Manthos A, Bontis J (July 2005). “Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in uterine cervices with coexistent grade I and grade III intraepithelial neoplasia: biologic progression or independent lesions?”. 《European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology》 121 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.024. PMID 15949888.

- ↑ 가 나 Jensen KE, Schmiedel S, Frederiksen K, Norrild B, Iftner T, Kjær SK (November 2012). “Risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse in relation to smoking among women with persistent human papillomavirus infection”. 《Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention》 21 (11): 1949–1955. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0663. PMC 3970163. PMID 23019238.

- ↑ 가 나 “Cervical Cancer Prevention”. 《PDQ》. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. 2022년 12월 26일.

- ↑ Cecil Medicine: Expert Consult Premium Edition . ISBN 1437736084, 9781437736083. Page 1317.

- ↑ Berek and Hacker's Gynecologic Oncology. ISBN 0781795125, 9780781795128. Page 342

- ↑ Cronjé HS (February 2004). “Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries”. 《International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics》 84 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.09.009. PMID 14871510. S2CID 21356776.

- ↑ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). 《Robbins Basic Pathology》 8판. Saunders Elsevier. 718–721쪽. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ Sellors JW (2003). 〈Chapter 4: An introduction to colposcopy: indications for colposcopy, instrumentation, principles and documentation of results〉. 《Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners' manual》. International Agency for Research on Cancer. ISBN 978-92-832-0412-1.

- ↑ Pannu HK, Corl FM, Fishman EK (September–October 2001). “CT evaluation of cervical cancer: spectrum of disease”. 《Radiographics》 21 (5): 1155–1168. doi:10.1148/radiographics.21.5.g01se311155. PMID 11553823.

- ↑ Galaal K, Bryant A, Deane KH, Al-Khaduri M, Lopes AD (December 2011). “Interventions for reducing anxiety in women undergoing colposcopy”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2022 (12): CD006013. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006013.pub3. PMC 4161490. PMID 22161395.

- ↑ “Cancer Research UK website”. 2009년 1월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2009년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 DeMay M (2007). 《Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition.》. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-549-7.

- ↑ Garcia A, Hamid O, El-Khoueiry A (2006년 7월 6일). “Cervical Cancer”. 《eMedicine》. WebMD. 2007년 12월 9일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Dolinsky C (2006년 7월 17일). “Cervical Cancer: The Basics”. 《OncoLink》 (Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania). 2008년 1월 18일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ “What Is Cervical Cancer?”. American Cancer Society.

- ↑ “Cervical cancer – Types and grades”. Cancer Research UK.

- ↑ “Cancer Research UK website”. 2009년 1월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2009년 1월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Turashvili G. “Squamous cell carcinoma and variants”. 《Pathology Outlines》.

- ↑ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). 《Robbins Basic Pathology》 8판. Saunders Elsevier. 718–721쪽. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ↑ Mulita F, Iliopoulos F, Kehagias I (September 2020). “A rare case of gastric-type mucinous endocervical adenocarcinoma in a 59-year-old woman”. 《Przeglad Menopauzalny = Menopause Review》 19 (3): 147–150. doi:10.5114/pm.2020.99563. PMC 7573334. PMID 33100952.

- ↑ Bhatla N, Berek JS, Cuello Fredes M, Denny LA, Grenman S, Karunaratne K, 외. (April 2019). “Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri”. 《International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics》 145 (1): 129–135. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12749. PMID 30656645. S2CID 58656013.

- ↑ Canavan TP, Doshi NR (March 2000). “Cervical cancer”. 《American Family Physician》 61 (5): 1369–1376. PMID 10735343. 2005년 2월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Payne N, Chilcott J, McGoogan E (2000). “Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: a rapid and systematic review”. 《Health Technology Assessment》 4 (18): 1–73. doi:10.3310/hta4180. PMID 10932023.

- ↑ Karnon J, Peters J, Platt J, Chilcott J, McGoogan E, Brewer N (May 2004). “Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: an updated rapid and systematic review and economic analysis”. 《Health Technology Assessment》 8 (20): iii, 1–iii, 78. doi:10.3310/hta8200. PMID 15147611.

- ↑ “Liquid Based Cytology (LBC): NHS Cervical Screening Programme”. 2011년 1월 8일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2010년 10월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, 외. (March 2010). “European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. Second edition--summary document”. 《Annals of Oncology》 21 (3): 448–458. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC 2826099. PMID 20176693.

- ↑ 가 나 “Cervical Cancer Prevention”. 《PDQ》. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. 2022년 12월 26일.

- ↑ Staley H, Shiraz A, Shreeve N, Bryant A, Martin-Hirsch PP, Gajjar K (September 2021). “Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2021 (9): CD002834. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002834.pub3. PMC 8543674. PMID 34694000.

- ↑ 가 나 다 “Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines for Average-Risk Women” (PDF). 《cdc.gov》. 2015년 2월 1일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 11월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (November 2012). “ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131: Screening for cervical cancer”. 《Obstetrics and Gynecology》 120 (5): 1222–1238. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318277c92a. PMID 23090560.

- ↑ Karjane N, Chelmow D (June 2013). “New cervical cancer screening guidelines, again”. 《Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America》 40 (2): 211–223. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2013.03.001. PMID 23732026.

- ↑ 가 나 Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, 외. (August 2018). “Screening for Cervical Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement”. 《JAMA》 320 (7): 674–686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897. PMID 30140884.

- ↑ Arrossi S, Temin S, Garland S, Eckert LO, Bhatla N, Castellsagué X, 외. (October 2017). “Primary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Resource-Stratified Guideline”. 《Journal of Global Oncology》 3 (5): 611–634. doi:10.1200/JGO.2016.008151. PMC 5646902. PMID 29094100.

- ↑ 가 나 다 《Comprehensive cervical cancer control. A guide to essential practice》 Seco판. World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-92-4-154895-3. 2015년 5월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ 가 나 “Cervical Cancer Prevention”. 《PDQ》. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. 2022년 12월 26일.

- ↑ Manhart LE, Koutsky LA (November 2002). “Do condoms prevent genital HPV infection, external genital warts, or cervical neoplasia? A meta-analysis”. 《Sexually Transmitted Diseases》 29 (11): 725–735. doi:10.1097/00007435-200211000-00018. PMID 12438912. S2CID 9869956.

- ↑ Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, da Rosa MI, Bozzetti MC, Zanini RR (October 2009). “Efficacy of human papillomavirus vaccines: a systematic quantitative review”. 《International Journal of Gynecological Cancer》 19 (7): 1166–1176. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3d100. PMID 19823051. S2CID 24695684.

- ↑ Arrossi S, Temin S, Garland S, Eckert LO, Bhatla N, Castellsagué X, 외. (October 2017). “Primary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Resource-Stratified Guideline”. 《Journal of Global Oncology》 3 (5): 611–634. doi:10.1200/JGO.2016.008151. PMC 5646902. PMID 29094100.

- ↑ 가 나 다 “Health ministry withdraws recommendation for cervical cancer vaccine”. 《The Asahi Shimbun》. 2013년 6월 15일. 2013년 6월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Zhang X, Dai B, Zhang B, Wang Z (February 2012). “Vitamin A and risk of cervical cancer: a meta-analysis”. 《Gynecologic Oncology》 124 (2): 366–373. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.012. PMID 22005522.

- ↑ Myung SK, Ju W, Kim SC, Kim H (October 2011). “Vitamin or antioxidant intake (or serum level) and risk of cervical neoplasm: a meta-analysis”. 《BJOG》 118 (11): 1285–1291. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03032.x. hdl:2027.42/86903. PMID 21749626. S2CID 38761694.

- ↑ “Cervical Cancer Treatment Options | Treatment Choices by Stage”. 《www.cancer.org》. 2020년 9월 12일에 확인함.

- ↑ Baalbergen A, Veenstra Y, Stalpers L (January 2013). “Primary surgery versus primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy for early adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2021 (1): CD006248. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006248.pub3. PMC 7387233. PMID 23440805.

- ↑ Einhorn N, Tropé C, Ridderheim M, Boman K, Sorbe B, Cavallin-Ståhl E (2003). “A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in cervical cancer (cervix uteri)”. 《Acta Oncologica》 42 (5–6): 546–556. doi:10.1080/02841860310014660. PMID 14596512.

- ↑ Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration (CCCMAC) (January 2010). “Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: individual patient data meta-analysis”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2010 (1): CD008285. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008285. PMC 7105912. PMID 20091664.

- ↑ Chau JP, Liu X, Lo SH, Chien WT, Hui SK, Choi KC, Zhao J (March 2022). “Perioperative enhanced recovery programmes for women with gynaecological cancers”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2022 (3): CD008239. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008239.pub5. PMC 8922407. PMID 35289396.

- ↑ van Nagell JR, Greenwell N, Powell DF, Donaldson ES, Hanson MB, Gay EC (April 1983). “Microinvasive carcinoma of the cervix”. 《American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology》 145 (8): 981–991. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(83)90852-9. PMID 6837683.

- ↑ Erstad S (2007년 1월 12일). “Cone biopsy (conization) for abnormal cervical cell changes”. 《WebMD》. 2007년 11월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lin Y, Zhou J, Dai L, Cheng Y, Wang J (September 2017). “Vaginectomy and vaginoplasty for isolated vaginal recurrence 8 years after cervical cancer radical hysterectomy: A case report and literature review”. 《The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research》 43 (9): 1493–1497. doi:10.1111/jog.13375. PMID 28691384. S2CID 42161609.

- ↑ Kokka F, Bryant A, Brockbank E, Jeyarajah A (May 2014). “Surgical treatment of stage IA2 cervical cancer”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2018 (5): CD010870. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010870.pub2. PMC 6513277. PMID 24874726.

- ↑ Jones WB, Mercer GO, Lewis JL, Rubin SC, Hoskins WJ (October 1993). “Early invasive carcinoma of the cervix”. 《Gynecologic Oncology》 51 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1006/gyno.1993.1241. PMID 8244170.

- ↑ Dolson L (2001). “Trachelectomy”. 2007년 9월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Burnett AF (February 2006). “Radical trachelectomy with laparoscopic lymphadenectomy: review of oncologic and obstetrical outcomes”. 《Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology》 18 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000192968.75190.dc. PMID 16493253. S2CID 22958941.

- ↑ Cibula D, Ungár L, Svárovský J, Zivný J, Freitag P (March 2005). “[Abdominal radical trachelectomy--technique and experience]”. 《Ceska Gynekologie》 (체코어) 70 (2): 117–122. PMID 15918265.

- ↑ Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, Roy M (July 2005). “Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early-stage cervical cancer. A series of 50 pregnancies and review of the literature”. 《Gynecologic Oncology》 98 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.014. PMID 15936061.

- ↑ Roy M, Plante M, Renaud MC, Têtu B (September 1996). “Vaginal radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer”. 《Gynecologic Oncology》 62 (3): 336–339. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0245. PMID 8812529.

- ↑ Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P (April 2000). “Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a treatment to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients”. 《Cancer》 88 (8): 1877–1882. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000415)88:8<1877::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 10760765.

- ↑ Schlaerth JB, Spirtos NM, Schlaerth AC (January 2003). “Radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with uterine preservation in the treatment of cervical cancer”. 《American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology》 188 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.124. PMID 12548192.

- ↑ 가 나 Rogers L, Siu SS, Luesley D, Bryant A, Dickinson HO (May 2012). “Radiotherapy and chemoradiation after surgery for early cervical cancer”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 5 (5): CD007583. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007583.pub3. PMC 4171000. PMID 22592722.

- ↑ Waggoner SE (June 2003). “Cervical cancer”. 《Lancet》 361 (9376): 2217–2225. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13778-6. PMID 12842378. S2CID 24115541.

- ↑ Falcetta FS, Medeiros LR, Edelweiss MI, Pohlmann PR, Stein AT, Rosa DD (November 2016). “Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy for early stage cervical cancer”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 11 (11): CD005342. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005342.pub4. PMC 4164460. PMID 27873308.

- ↑ Nama V, Angelopoulos G, Twigg J, Murdoch JB, Bailey J, Lawrie TA (October 2018). “Type II or type III radical hysterectomy compared to chemoradiotherapy as a primary intervention for stage IB2 cervical cancer”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2018 (10): CD011478. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011478.pub2. PMC 6516889. PMID 30311942.

- ↑ “FDA Approves First Drug Treatment for Late-Stage Cervical Cancer”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2006년 6월 15일. 2007년 10월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 12월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Moon JY, Song IC, Ko YB, Lee HJ (April 2018). “The combination of cisplatin and topotecan as a second-line treatment for patients with advanced/recurrent uterine cervix cancer”. 《Medicine》 97 (14): e0340. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010340. PMC 5902288. PMID 29620661.

- ↑ Tangjitgamol S, Katanyoo K, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, Manusirivithaya S, Supawattanabodee B (December 2014). “Adjuvant chemotherapy after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2019 (12): CD010401. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010401.pub2. PMC 6402532. PMID 25470408.

- ↑ 가 나 Sardain H, Lavoue V, Redpath M, Bertheuil N, Foucher F, Levêque J (August 2015). “Curative pelvic exenteration for recurrent cervical carcinoma in the era of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A systematic review” (PDF). 《European Journal of Surgical Oncology》 41 (8): 975–985. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2015.03.235. PMID 25922209. S2CID 21911045.

- ↑ Lanceley A, Fiander A, McCormack M, Bryant A, 외. (Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro-oncology and Orphan Cancer Group) (November 2013). “Follow-up protocols for women with cervical cancer after primary treatment”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 2014 (11): CD008767. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008767.pub2. PMC 8969617. PMID 24277645.

- ↑ Eleje GU, Eke AC, Igberase GO, Igwegbe AO, Eleje LI (March 2019). “Palliative interventions for controlling vaginal bleeding in advanced cervical cancer”. 《The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews》 3 (3): CD011000. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011000.pub3. PMC 6423555. PMID 30888060.

- ↑ “Enforcement Reports” (PDF).

- ↑ “Seagen and Genmab Announce FDA Accelerated Approval for Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin-tftv) in Previously Treated Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical Cancer”. Seagen. 2021년 9월 20일. 2021년 9월 20일에 확인함 – Business Wire 경유.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 “‘자궁경부암 백신’ 여학생 47만명에 무료 접종, 그런데… 보도되지 않은 ‘심각한’ 부작용”. 2016년 7월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 7월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 아 자 차 카 타 “예방접종 도우미 > 예방접종길잡이 > 국가 예방접종 사업 소개 > 건강여성 첫걸음 클리닉 사업 > HPV 백신 알아보기”. 2020년 9월 27일에 확인함.

- ↑ “EMA to further clarify safety profile of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines”. 13/07/2015.

참고 문헌

- 국가건강정보포털 자궁경부암의 방사선치료: 자궁경부암의 원인

- 김영태, <<자궁경부암의 원인 및 진단>>, 대한의사협회지, 2006년

- 국가암정보센터 암의종류

- 자궁경부암의 원인과 증상 및 치료. 2010

![침습성 편평상피세포암은 문합하는 세포 둥지 또는 단일 세포의 침윤이 특징적이다.[63] 이 사진은 분화도가 낮은 저분자암이다. H&E 염색](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Histopathology_of_squamous_cell_carcinoma_of_the_cervix.png/380px-Histopathology_of_squamous_cell_carcinoma_of_the_cervix.png)