사용자:배우는사람/문서:Chapter I - The Gods Of Egypt (32-41)

Chapter I - The Gods Of Egypt (pp. 32~41)

[편집]The Goddess Nit

[편집]네이트 컬트의 중심지: 사이스

[편집]The cult of Nit, or Neith, must have been very general in Egypt, although in dynastic times the chief seat thereof was at Saïs in the Delta, and we know that devotees of the goddess lived as far south as Naḳâda, a few miles to the north of Thebes, for several objects inscribed with the name of queen Nit-hetep have been found [Page 32] in a grave at that place.

| Neithhotep | |

|---|---|

| Queen consort of Egypt | |

Bone label of queen Neithhotep on display at the British Museum. | |

| Full name | Neithhotep |

| Buried | Naqada, "Great Tomb" |

| Consort | King Narmer |

| Issue | King Hor-Aha and maybe Benerib |

| Dynasty | 1st dynasty of Egypt |

| ||

| Neithhotep [1] | ||

|---|---|---|

| 구왕국 시대 (2686–2181 BC) | ||

| 신성문자 표기 |

Neithhotep (or Hetepu-Neith) was the first queen of ancient Egypt, cofounder of the First dynasty, and is the earliest woman in history whose name is known. The name Neithhotep means "[The Goddess] Neith is satisfied".

Biography

Neithhotep's dynastic marriage to Narmer, which could represent the start of the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt, c. 3200 BCE with the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt, may be represented on the Narmer Macehead.[2] Indeed, in this view Neithhotep was originally a princess of Lower Egypt, before marriage to Narmer (Thinite king of Upper Egypt). An alternative theory, based on the location of her tomb, holds that Neithhotep was a member of the royal line of Naqada.

Neithhotep was the wife of Narmer[1][3] or wife[4] or mother of Hor-Aha and possibly the mother of Benerib, Hor-Aha's wife.

Neithhotep's name was found in several locations:

- Clay sealing in the tomb at Naqada with the names of Hor-Aha and Neithhotep.[3][5]

- Clay sealing with the name of Neithhotep alone, also from the royal tomb in Naqada. Some of these are now in the Cairo Museum.[6]

- Two inscribed vases were found in the tomb of Djer, Neithhotep's grandson.[7]

- Ivory fragments with the name of Neithhotep were discovered in the subsidiary tombs near Djer's funerary complex.[7]

- A fragment of an alabaster vase with the name of Neithhotep was found in the general vicinity of the royal tombs in Umm el-Qaab.[8]

- On labels from Helwan.[3]

Her titles were: ḫntỉ (Foremost of Women), sm3ỉ.t nb.tỉ (Consort of the Two Ladies). Both were titles given to queens during the First dynasty.[1]

Tomb

Neithhotep tomb was a large mastaba first excavated by Jacques de Morgan [9] at the end of the 19th century and now lost due to erosion.

Vessel inscriptions, labels and sealings from the graves of both Hor-Aha and Queen Neithhotep suggest that this queen died during the reign of Hor-Aha and that she was his mother.[10] The selection of the cemetery of Naqada as the resting place of Neithhotep is a strong indication that she came from this province. This, in turn, supports the view that Narmer married her because she was a member of the ancient royal line of Naqada.[11]

네이트: 사냥의 여신

[편집]Of the early worship of the goddess nothing is known, but it is most probable that she was adored as a great hunting spirit as were adored (숭배하다) spirits of like character by primitive peoples in other parts of the world. The crossed arrows and shield indicate that she was a hunting spirit in the earliest times,

| Neith | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

the Egyptian goddess Neith bearing her war goddess symbols, the crossed arrows and shield on her head, the ankh and the was staff. She sometimes wears the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. | |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||||

| Major cult center | Sais | ||||

| Symbol | the bow, the shield, the crossed arrows | ||||

| Consort | Khnum or Set (mythology) | ||||

| Offspring | Sobek or Ra and Apep | ||||

Neith (/neɪθ/ or /niːθ/; also spelled Nit, Net, or Neit) was an early goddess in the Egyptian pantheon. She was the patron deity of Sais, where her cult was centered in the Western Nile Delta of Egypt and attested as early as the First Dynasty.[12] The Ancient Egyptian name of this city was Zau.

Neith also was one of the three tutelary deities of the ancient Egyptian southern city of Ta-senet or Iunyt now known as Esna (Arabic: إسنا), Greek: Λατόπολις (Latopolis), or πόλις Λάτων (Polis Laton), or Λάττων (Laton); Latin: Lato), which is located on the west bank of the River Nile, some 55 km south of Luxor, in the modern Qena Governorate.

Name and symbolism

Neith was a goddess of war and of hunting and had as her symbol, two arrows crossed over a shield. Her symbol also identified the city of Sais.[13] This symbol was displayed on top of her head in Egyptian art. In her form as a goddess of war, she was said to make the weapons of warriors and to guard their bodies when they died.

Her name also may be interpreted as meaning water. In time, this led to her being considered as the personification of the primordial waters of creation. She is identified as a great mother goddess in this role as a creator.

Neith's symbol and part of her hieroglyph also bore a resemblance to a loom, and so later in the history of Egyptian myths, she also became goddess of weaving, and gained this version of her name, Neith, which means weaver. At this time her role as a creator changed from being water-based to that of the deity who wove all of the world and existence into being on her loom.

In art, Neith sometimes appears as a woman with a weavers’ shuttle atop her head, holding a bow and arrows in her hands. At other times she is depicted as a woman with the head of a lioness, as a snake, or as a cow.

Sometimes Neith was pictured as a woman nursing a baby crocodile, and she was titled "Nurse of Crocodiles". As the personification of the concept of the primordial waters of creation in the Ogdoad theology, she had no gender. As mother of Ra, she was sometimes described as the "Great Cow who gave birth to Ra".

Neith was considered to be a goddess of wisdom and was appealed to as an arbiter in the dispute between Horus and Seth.

Attributes

As a goddess of weaving and the domestic arts she was a protector of women and a guardian of marriage, so royal women often named themselves after Neith, in her honor. Since she also was goddess of war, and thus had an additional association with death, it was said that she wove the bandages and shrouds worn by the mummified dead as a gift to them, and thus she began to be viewed as a protector of one of the Four sons of Horus, specifically, of Duamutef, the deification of the canopic jar storing the stomach, since the abdomen (often mistakenly associated as the stomach) was the most vulnerable portion of the body and a prime target during battle. It was said that she shot arrows at any evil spirits who attacked the canopic jar she protected.

Mythology

In the late pantheon of the Ogdoad myths, she became identified as the mother of Ra and Apep. When she was identified as a water goddess, she was also viewed as the mother of Sobek, the crocodile.[14] It was this association with water, i.e. the Nile, that led to her sometimes being considered the wife of Khnum, and associated with the source of the River Nile. She was associated with the Nile Perch as well as the goddess of the triad in that cult center.

As the goddess of creation and weaving, she was said to reweave the world on her loom daily. An interior wall of the temple at Esna records an account of creation in which Neith brings forth from the primeval waters of the Nun the first land ex nihilo. All that she conceived in her heart comes into being including the thirty gods. Having no known husband she has been described as "Virgin Mother Goddess":

Unique Goddess, mysterious and great who came to be in the beginning and caused everything to come to be . . . the divine mother of Re, who shines on the horizon . . .[15]

Proclus (412–485 AD) wrote that the adyton of the temple of Neith in Sais (of which nothing now remains) carried the following inscription:

I am the things that are, that will be, and that have been. No one has ever laid open the garment by which I am concealed. The fruit which I brought forth was the sun.[16]

It was said that Neith interceded in the kingly war between Horus and Set, over the Egyptian throne, recommending that Horus rule.

A great festival, called the Feast of Lamps, was held annually in her honor and, according to Herodotus, her devotees burned a multitude of lights in the open air all night during the celebration.

Syncretic relationships

A Hellenistic royal family ruled over Egypt for three centuries, a period called the Ptolemaic dynasty until the Roman conquest in 30 B.C. Anouke, a goddess from Asia Minor was worshiped by immigrants to ancient Egypt. This war goddess was shown wearing a curved and feathered crown and carrying a spear, or bow and arrows. Within Egypt, she was later assimilated and identified as Neith, who by that time had developed her aspects as a war goddess.

The Greek historian, Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC), noted that the Egyptian citizens of Sais in Egypt worshipped Neith and that they identified her with Athena. The Timaeus, a Socratic dialogue written by Plato, mirrors that identification with Athena, possibly as a result of the identification of both goddesses with war and weaving.[17]

E. A. Wallis Budge argued that the spread of Christianity in Egypt was influenced by the likeness of attributes between the Mother of Christ and goddesses such as Isis and Neith. Partheno-genesis was associated with Neith long before the birth of Christ and other properties belonging to her and Isis were transferred to the Mother of Christ by way of the apocryphal gospels as a mark of honour.[18]

See also

People named after Neith:

- Neithhotep, first recorded Egyptian queen

- Merneith, queen regent

네이트: 악어신 세베트의 어머니

[편집]but a picture of the dynastic period represents her (즉, Neith) with two crocodiles20) sucking one at each breast, and thus she appears in later times to have had ascribed to her power over the river.

| Sobek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| The Nile, The Army and Military, Fertility | |||||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

or

| ||||||

| Major cult center | Crocodilopolis, Faiyum, Kom Ombo | ||||||

| Symbol | crocodile | ||||||

| Parents | Set and Neith | ||||||

| Siblings | Anubis | ||||||

Sobek (also called Sebek, Sochet, Sobk, and Sobki), and in Greek, Suchos (Σοῦχος) was an ancient Egyptian deity with a complex and fluid nature.[19] He is associated with the Nile crocodile and is either represented in its form or as a human with a crocodile head. Sobek was also associated with pharaonic power, fertility, and military prowess, but served additionally as a protective deity with apotropaic qualities, invoked particularly for protection against the dangers presented by the Nile river.

History

Sobek enjoyed a longstanding presence in the ancient Egyptian pantheon, from the Old Kingdom (c. 2686—2181 BCE) through the Roman period (c. 30 BCE—350 CE). He is first known from several different Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, particularly from spell PT 317.[20] The spell, which praises the pharaoh as living incarnation of the crocodile god, reads:

As one can understand from this text alone, Sobek was considered a violent, hyper-sexual, and erratic deity, prone to his primal whims. The origin of his name, Sbk[22] in ancient Egyptian, is debated among scholars, but many believe that it is derived from a causative of the verb "to impregnate."[23]

Though Sobek was worshipped in the Old Kingdom, he truly gained prominence in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055—1650 BCE), most notably under the Twelfth Dynasty king, Amenemhat III. Amenemhat III had taken a particular interest in the Faiyum region of Egypt, a region heavily associated with Sobek. Amenemhat and many of his dynastic contemporaries engaged in building projects to promote Sobek – projects that were often executed in the Faiyum. In this period, Sobek also underwent an important change: he was often fused with the falcon-headed god of divine kingship, Horus. This brought Sobek even closer with the kings of Egypt, thereby giving him a place of greater prominence in the Egyptian pantheon.[24] The fusion added a finer level of complexity to the god’s nature, as he was adopted into the divine triad of Horus and his two parents: Osiris and Isis.[25]

Sobek first acquired a role as a solar deity through his connection to Horus, but this was further strengthened in later periods with the emergence of Sobek-Ra, a fusion of Sobek and Egypt’s primary sun god, Ra. Sobek-Horus persisted as a figure in the New Kingdom (1550—1069 BCE), but it was not until the last dynasties of Egypt that Sobek-Ra gained prominence. This understanding of the god was maintained after the fall of Egypt’s last native dynasty in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt (c. 332 BCE—390 CE). The prestige of both Sobek and Sobek-Ra endured in this time period and tributes to him attained greater prominence – both through the expansion of his dedicated cultic sites and a concerted scholarly effort to make him the subject of religious doctrine.[26]

Cult centers

The entire Faiyum region — the "Land of the Lake" in Egyptian (specifically referring to Lake Moeris) — served as a cult center of Sobek.[27] Most Faiyum towns developed their own localized versions of the god, such as Soknebtunis at Tebtunis, Sokonnokonni at Bacchias, and Souxei at an unknown site in the area. At Karanis, two forms of the god were worshipped: Pnepheros and Petsuchos. There, mummified crocodiles were employed as cult images of Petsuchos.[28]

Sobek Shedety, the patron of the Faiyum's centrally located capital, Crocodilopolis (or Egyptian "Shedet"), was the most prominent form of the god. Extensive building programs honoring Sobek were realized in Shedet, as it was the capital of the entire Arsinoite nome and consequently the most important city in the region. It is thought that the effort to expand Sobek's main temple was initially driven by Ptolemy II.[27] Specialized priests in the main temple at Shedet functioned solely to serve Sobek, boasting titles like "prophet of the crocodile-gods" and "one who buries of the bodies of the crocodile-gods of the Land of the Lake."[29]

Outside the Faiyum, Kom Ombo, in southern Egypt, was the biggest cultic center of Sobek, particularly during the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. The temple at this site was called the "Per-Sobek," meaning the "house of Sobek."[29]

Character and surrounding mythologies

Sobek is, above all else, an aggressive and animalistic deity who lives up to the vicious reputation of his patron animal, the large and violent Nile crocodile. Some of his common epithets betray this nature succinctly, the most notable of which being: "he who loves robbery," "he who eats while he also mates," and "pointed of teeth."[30] However, he also displays grand benevolence in more than one celebrated myth. After his association with Horus and consequent adoption into the Osirian triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus in the Middle Kingdom, Sobek became associated with Isis as a healer of the deceased Osiris (following his violent murder by Set in the central Osiris myth).[31] In fact, though many scholars believe that the name of Sobek, Sbk, is derived from s-bAk, "to impregnate," others postulate that it is a participial form of the verb sbq,[32] an alternative writing of sAq, "to unite," thereby meaning Sbk could roughly translate to "he who unites (the dismembered limbs of Osiris)."[33]

It is from this association with healing that Sobek was considered a protective deity. His fierceness was able to ward off evil while simultaneously defending the innocent. He was thusly made a subject of personal piety and a common recipient of votive offerings, particularly in the later periods of ancient Egyptian history. It was not uncommon, particularly in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, for crocodiles to be preserved as mummies in order to present at Sobek’s cultic centers.[34] Sobek was also offered mummified crocodile eggs, meant to emphasize the cyclical nature of his solar attributes as Sobek-Ra.[35] Likewise, crocodiles were raised on religious grounds as living incarnations of Sobek. Upon their deaths, they were mummified in a grand ritual display as sacred, but earthly, manifestations of their patron god. This practice was executed specifically at the main temple of Crocodilopolis.[36] It should also be mentioned that these mummified crocodiles have been found with baby crocodiles in their mouths and on their backs. The crocodile – one of the few non-mammals that diligently care for their young – often transports its offspring in this manner. The practice of preserving this aspect of the animal’s behavior via mummification is likely intended to emphasize the protective and nurturing aspects of the fierce Sobek, as he protects the Egyptian people in the same manner that the crocodile protects its young.[37]

In Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, a "local monograph" called the Book of the Faiyum centered on Sobek with a considerable portion devoted to the journey made by Sobek-Ra each day with the movement of the sun through the sky. The text also focuses heavily on Sobek’s central role in creation as a manifestation of Ra, as he is said to have risen from the primal waters of Lake Moeris, not unlike the Ogdoad in the traditional creation myth of Hermopolis.[38]

Many varied copies of the book exist and many scholars feel that it was produced in large quantities as a "best-seller" in antiquity. The integral relationship between the Faiyum and Sobek is highlighted via this text, and his far reaching influence is seen in localities that are outside of the Faiyum as well; a portion of the book is copied on the Upper Egyptian (meaning southern Egyptian) Temple of Kom Ombo.[39]

Gallery

-

Sobek in his crocodile form, 12th Dynasty. Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich.

-

This New Kingdom statue shows pharaoh Amenhotep III with a solar form of Sobek, likely Sobek-Horus. Luxor Museum, Luxor.

-

Crocodiles of various ages mummified in honor of Sobek. The Crocodile Museum, Aswan.

-

Mummified crocodiles. The Crocodile Museum, Aswan.

-

A wall relief from Kom Ombo showing Sobek with solar attributes.

-

This dark blue glass head served as an inlay. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Bibliography

- Allen, James P. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005.

- Bresciani, Edda. “Sobek, Lord of the Land of the Lake.” In Divine Creatures : Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, edited by Salima Ikram, 199-206. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

- Frankfurter, David. Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-691-07054-7.

- Ikram, Salima. “Protecting Pets and Cleaning Crocodiles: The Animal Mummy Project.” Divine Creatures : Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, edited by Salima Ikram, 207-227. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

- Murray, Mary Alice. The Splendor that was Egypt. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1963.

- O’Connor, David. “From Topography to Cosmos: Ancient Egypt’s Multiple Maps.” In Ancient Perspectives: Maps and Their Place in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome, edited by Richard J.A. Talbert, 47 – 79. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Tait, John. “The ‘Book of the Fayum’: Mystery in a Known Landscape.” In Mysterious Lands, edited by David O’Connor and Stephen Quirke, 183 – 202. Portland: Cavendish Publishing, 2003.

- Zecchi, Marco. Sobek of Shedet : The Crocodile God in the Fayyum in the Dynastic Period. Umbria: Tau Editrice, 2010.

Further reading

- Beinlich, Horst. Das Buch vom Fayum : zum religiösen Eigenverständnis einer ägyptischen Landschaft. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1991.

- Dolzani, Claudia. Il Dio Sobk. Roma: Accademia nazionale dei Lincei, 1961.

See also

- Amenemhat III

- Animal mummy

- Book of the Faiyum

- Crocodilopolis

- Faiyum

- Horus

- Kom Ombo

- Nile crocodile

- Ra

External links

![]() 위키미디어 공용에 Sobek 관련 미디어 분류가 있습니다.

위키미디어 공용에 Sobek 관련 미디어 분류가 있습니다.

이집트인들의 신에 대한 관념: 인간과 닮았음

[편집]It has already been said that the primitive Egyptians, though believing that their gods possessed powers superior to their own, regarded them as beings who were liable to grow old and die, and who were moved to love and to hate, and to take pleasure in meat and drink like man; they were even supposed to intermarry with human beings and to have the power of begetting offspring like the “sons of God,” as recorded in the Book of Genesis (vi. 2, 4).

These ideas were common in all periods of Egyptian history, and it is clear that the Egyptians never wholly freed themselves from them; there is, in fact, abundant proof that even in the times when monotheism had developed in a remarkable degree they clung to them with a tenacity which is surprising (놀라운, 놀랄).

The religious texts contain numerous references to them, and beliefs which were conceived by the Egyptians in their lowest states of civilization are mingled with those which reveal the existence of high spiritual conceptions. The great storehouse of religious thought is the Book of the Dead, and in one of the earliest Recensions of that remarkable work we may examine its various layers with good result. In these are preserved many passages which throw light upon the views which were held concerning the gods, and the powers which they possessed, and the place where they dwelt in company with the beatified (시복하다) dead.

King Unȧs as a God

[편집]Unȧs 피라미드 텍스트

[편집]One of the most instructive of these passages for our purpose forms one of the texts which are inscribed on the walls and corridors of the chambers in the pyramid tombs of Unȧs, a king of the Vth Dynasty, and of Tetȧ, a king of the VIth Dynasty.

[Page 33] The paragraphs in general of the great Heliopolitan Recension deal, as we should expect, with the offerings which were to be made at stated intervals in the little chapels attached to the pyramids, and many were devoted to the object of removing enemies of every kind from the paths of the king in the Underworld ; others contain hymns, and short prayers for his welfare, and magical formulae, and incantations. A few describe the great power which the beatified king enjoys in the world beyond the grave, and, of course, declare that the king is as great a lord in heaven as he was upon earth.

| Unas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Funerary chamber of Unas' pyramid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh of Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2375–2345 BC, 5th Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Djedkare Isesi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Teti | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort(s) | Nebet, Khenut | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Unas-ankh, Iput, Hemetre, Khentkaues, Neferut, Nefertkaues, Sesheshet Idut | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Unas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unas /ˈjuːnəs/ or Oenas (/ˈiːnəs/; also spelled Unis or Wenis) was a Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, and the last ruler of the Fifth dynasty from the Old Kingdom.[40] His reign has been dated between 2375 BC and 2345 BC.[41] Unas is believed to have had two queens, Nebet and Khenut, based on their burials near his tomb.[42]

With his death, the Fifth dynasty came to an end, according to Manetho; he probably had no sons. Furthermore, the Turin King List inserts a break at this point, which "gives us some food for thought," writes Jaromir Malek, "because the criterion for such divisions in the Turin Canon invariably was the change of location of the capital and royal residence."[43] However, there are several instances of uninterrupted continuity between the Fifth and the sixth dynasties: Kagemni, the vizer of Unas's successor Teti, began his career under Djedkare Isesi and Unas. Teti's queen, Iput, is believed to have been the daughter of Unas, which shows Teti, Nicolas Grimal argues, "made no conscious break with the preceding dynasty."[44] The break between the two dynasties may have been more as an official act than in fact.

The Pyramid Texts

He built a small pyramid at Saqqara, originally named "Beautiful are the places of Unas", close to the Step Pyramid of Djoser. It has been excavated by Vyse, Barsanti, Gaston Maspero, Firth, Selim Hassan, A. Husein, and Alexandre Piankoff.[45] Its interior is decorated with a number of reliefs detailing events during his reign as well as a number of inscriptions. However, Jaromir Malek considers "the main innovation of Unas' pyramid, and one that was to be characteristic of the remaining pyramids of the Old Kingdom (including some of the queens), was the first appearance of the Pyramid Texts".[46] These texts were inscribed in Sixth Dynasty royal versions, but Unas's texts contains verses and spells which were not included in the later 6th dynasty copies.[47] The pyramid texts were intended to help the king in overcoming hostile forces and powers in the Underworld and thus join with the Sun God Ra, his divine father in the afterlife.[48] The king would then spend his days in eternity sailing with Ra across the sky in a solar boat.[49]

An example of a pyramid Text here is given below:

- Re-Atum, this Unas comes to you, A spirit indestructible...Your son comes to you, This Unas comes to you, May you cross the sky united in the dark. May you rise in lightland, the place in which you shine! (Utterance 217)[49]

Technology

The causeway of Unas's pyramid complex includes a bas relief showing how they transported a palm column by boat on the Nile.[50]

In popular culture

- The American technical death metal band Nile have an 11:43-minute long song named "Unas, Slayer of the Gods" based on a myth about how Unas killed and ate the gods in order to achieve immortality. It appears on their 2002 album In Their Darkened Shrines.

- In the Sci-Fi TV series Stargate SG1, Unas is a species of sentient homonid and original host to the parasitic goa'uld - the main antagonist species throughout the story arc.

Gallery

-

Unas's name on a stela at Saqqara

-

Causeway of the Pyramid of Unas.

-

Palmiform column from the funeral complex of Unas in Saqqara. Now at the Louvre.

See also

| Teti | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sistrum inscribed with the name of Teti. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2345–2333 BC, 6th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Unas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Userkare | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort(s) | Iput I, Khuit, Khent(kaus III), Weret-Imtes? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Pepi I, Teti-ankh-kem, Seshseshet Watet-khet-her, Nebty-nubkhet Sesheshet (D), Inty? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Teti | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Teti, less commonly known as Othoes, was the first Pharaoh of the Sixth dynasty of Egypt and is buried at Saqqara. The exact length of his reign has been destroyed on the Turin King List, but is believed to have been about 12 years.

Biography

Teti had several wives:

- Queen Iput, likely the daughter of King Unas, the last king of the Fifth dynasty. Iput I was the mother of Pepi I

- Queen Khuit, who may have been the mother of Userkare (according to Jonosi and Callender) [51]

- Queen Khent (or Khentkaus III). Known from a relief of Pepi I's mortuary temple. She may have been buried in a mastaba.[51]

- Weret-Imtes? This queen is mentioned in the autobiography of Wenis. It may be a reference to the title of the queen instead of her personal name. She was involved in a harem plot to overthrow Pepi, but apparently was caught before she succeeded. In the tomb of the official Wenis there is mention of “a secret charge in the royal harem against the Great of Sceptre”.

Teti is known to have had several children. He was the father of at least three sons and probably ten daughters.[52] Of the sons, two are well attested, a third one is likely :

- Pepi I, whose mother is Queen Iput I

- Tetiankh, "eldest King’s son", whose mastaba is located on the east side of Queen Iput’s funerary complex[53]

- Nebkauhor, with the beautiful name of Idu, "king’s eldest son of his body", buried in the mastaba of Vizier Akhethetep/Hemi, in King Unis’cemetery. He is most probably Teti’s son, born of Queen Iput I and buried in a fallen Vizier’s tomb, within the funerary complex of his maternal grandfather [54]

According to N. Kanawati, King Teti had at least 9 daughters, by a number of wives, and the fact that they were named after his mother, Sesheshet, allows to trace his family. At least three princesses bearing the name Seshseshet are designated as " king’s eldest daughter ", meaning that there were at least three different queens. It seems that there was a tenth one, born of a fourth queen as she is also designated as " king’s eldest daughter ".

- Seshseshet whose beautiful name was Waatetkhéthor, married to Vizier Mereruka, in whose mastaba she has a chapel. She is designated as " king’s eldest daughter of his body ". She may have been the eldest daughter of Queen Iput I [55]

- Seshseshet with the beautiful name of Idut, "king’s daughter of his body", who died very young at the beginning of her father’s reign and was buried in the mastaba of Vizier Ihy, in King Unis’cemetery. She is most certainly Teti’s daughter, born of Queen Iput I and buried within the funerary complex of her maternal [55]

- Seshseshet called Nubkhetnebty, "king’s daughter of his body", wife of Vizier Kagemni, et represented in her husband’s mastaba. She was maybe also born of Queen Iout I [56]

- Seshseshet, also called Sathor, married to Isi, resident governor at Edfu and also totled vizier. She also would have been born of Queen Iput I.[57]

- Seshseshet, with the beautiful name of Sheshit, " king’s eldest daughter of his body and wife of the overseer of the great court Neferseshemptah, and is depicted in her husband’s mastaba. As she is an eldest daughter of the king, she cannot be born of the same mother as Waatkhetethor and therefore may have been a daughter of Queen Khuit [58]

- Seshseshet also called Sheshti, "king’s daughter of his body", married to the keeper of the head ornaments Shepsipuptah, and depicted in her husband’s mastaba.[59]

- Seshseshet with the beautiful name of Merout, entitled " king’s eldest daughter " but without the addition " of his body " and therefore born of a third, maybe a minor queen, and married to Ptahemhat [60]

- Seshseshet, wife of Remni, "sole companion" and overseer of the department of the palace guards[61]

- Seshseshet, married to Pepyankh Senior of Meir [62]

- the so-called " queen of the West Pyramid in King Pepy I cemetery. She is called " king’s eldest daughter of his body " and kings wife of Meryre mennefer (the name of Pepy I’s pyramid). Therefore she is a wife of King Pepi and most certainly his –half- sister [63] As she is also an eldest daughter of the king, her mother must be a fourth queen of Teti

Another possible daughter is princess Inti.[64]

During Teti's reign, high officials were beginning to build funerary monuments that rivaled that of the Pharaoh. His vizier, Mereruka, built a mastaba tomb at Saqqara which consisted of 33 richly carved rooms, the biggest known tomb for an Egyptian nobleman.[65] This is considered to be a sign that Egypt's wealth was being transferred from the central court to the officials, a slow process that culminated in the end to the Old Kingdom[출처 필요].

Manetho states that Teti was murdered by his palace bodyguards in a harem plot, but he may have been assassinated by the usurper Userkare . He was buried in the royal necropolis at Saqqara. His pyramid complex is associated with the mastabas of officials from his reign. Teti's Highest date is his Year after the 6th Count 3rd Month of Summer day lost (Year 12 if the count was biannual) from Hatnub Graffito No.1.[66] This information is confirmed by the South Saqqara Stone Annal document from Pepi II's reign which gives him a reign of around 12 years.

3rd "subsidiary" pyramid to Teti's tomb

Teti's mother was the Queen Sesheshet, who was instrumental in her son's accession to the throne and a reconciling of two warring factions of the royal family.[67] Sesheshet lived between 2323 BC to 2291 BC. Egypt's chief archaeologist Zahi Hawass, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, announced, on November 11, 2008, that she was entombed, in a 4,300-year-old headless 5 metre (16-foot-tall) Saqqara most complete subsidiary pyramid. This is the 118th pyramid discovered thus far in Egypt, the largest portion of its 2 metres wide beautiful casing was built with a superstructure 5 metres high. It originally reached 14 metres, with sides 22 metres long.[68][69]

Once 5 stories tall, it lay beneath 23 feet (7 meters) of sand, a small shrine and mud-brick walls from later periods. The 3rd known "subsidiary" pyramid to Teti's tomb, was originally 46 feet (14 meters) tall and 72 feet (22 meters) square at its base, due to its walls having stood at a 51-degree angle. Buried next to the Saqqara Step Pyramid, its base lies 65 feet underground and is believed to have been 50 feet tall when it was built.[70][71][72]

See also

Further reading

- Naguib Kanawati, Conspiracies in the Egyptian Palace: Unis to Pepy I, Routledge (2002), ISBN 0-415-27107-X.

External links

The Pyramid Complex of Unas is located in the pyramid field at Saqqara, near Cairo in Egypt.

The pyramid of Unas of the Fifth Dynasty (originally known as Beautiful are the places of Unas) is now ruined, and looks more like a small hill than a royal pyramid.

It was investigated by Perring and then Lepsius, but it was Gaston Maspero who first gained entry to the chambers in 1881, where he found texts covering the walls of the burial chambers. These together with others found in nearby pyramids of successive pharaohs are now known as the Pyramid Texts. He was the first pharaoh to include this, and he created the concept of having a number of magic spells inscribed on the walls of his tomb, intended to assist with the pharaoh's journey through the Duat and into the afterlife. This concept was thought to be so successful by other pharaohs that it soon evolved into the Coffin Texts in the Middle Kingdom, and then into the Book of the Dead from the beginning of the New Kingdom until the end of the Ptolemaic Period, when new texts began appearing.

In the burial chamber itself the remains of a mummy were found, including the skull, right arm and shin, but whether these belong to Unas is not certain. Near to the main pyramid, to the north east, there are mastabas that contain the burials of the consorts of the king.

The pyramid was built close to the pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara. The causeway was approximately 750m long and the unusual shape is because it follows a wadi. Material was taken from the complex of Djoser that was used to plug gaps in the wadi. The roof of the causeway was covered over to make a closed tunnel, with the exception of a long 'slot' that illuminated the walls that were decorated with brightly painted reliefs. [73]

It is believed that within the inscriptions of the Pyramid Text in Unas's tomb, there are also some lines of a Semitic dialect, written in Egyptian script and comprising the earliest evidence of written Semitic language.[74]

|

|

|

See also

- Verner, Miroslav, "The Pyramids – Their Archaeology and History", Atlantic Books, 2001, ISBN 1-84354-171-8

External links

- Pyramid Texts Online - Read the texts in situ. View the hieroglyphs and the complete translation.

Unȧs 피라미드 텍스트의 구절

[편집]The passage in question from the pyramid of Unȧs is of such interest and importance that it21) is given in the Appendix to this Chapter, with interlinear translation and transliteration, and with the variant readings from the pyramid of Tetȧ, but the following general rendering of its contents may be useful.

21) The hieroglyphic texts are given by Maspero, Les Inscriptions des Pyramides de Saqqarah, Paris, 1894, p. 67, 1. 496, and p. 134, 1. 319.

- “The sky poureth down rain, the stars tremble, the bow-bearers run about with hasty steps, the bones of Aker tremble, and those who are ministrants (보좌역) unto them betake themselves to flight (쏜살같이 도망치다) when they see Unȧs rising [in the heavens] like a god who liveth upon his fathers and feedeth upon his mothers.

- Unȧs is the lord of wisdom whose name his mother knoweth not. The noble estate (토지) of Unȧs is in heaven, and his strength in the horizon is like unto that of the god Tem his father, indeed, he is stronger than his father who gave him birth. The doubles (kau) of Unȧs are behind him, and those whom he hath conquered are beneath his feet.

- His gods are upon him, his uraei are upon his brow, his serpent-guide is before him, and his soul looketh upon the spirit of flame; the powers of Unȧs protect him.”

| Aker in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

ꜣkr | ||||

| ||||

In Egyptian mythology, Aker (also spelt Akar) was one of the earliest gods worshipped, and was the deification of the horizon. There are strong indications that Aker was worshipped before other known Egyptian gods of the earth, such as Geb.[출처 필요] Aker itself means (one who) curves because it was perceived that the horizon bends all around us. The Pyramid texts make an assertive statement that the Akeru (= 'those of the horizon', from the plural of aker) will not seize the pharaoh, stressing the power of the Egyptian pharaoh over the surrounding non-Egyptian peoples.

As the horizon, Aker was also seen as symbolic of the borders between each day, and so was originally depicted as a narrow strip of land (i.e. a horizon), with heads on either side, facing away from one another, a symbol of borders. These heads were usually those of lions. Over time, the heads became full figures of lions (still facing away from each other), one representing the concept of yesterday (Sef in Egyptian), and the other the concept of tomorrow (Duau in Egyptian).[76]

Consequently, Aker often became referred to as Ruti, the Egyptian word meaning two lions. Between them would often appear the hieroglyph for horizon, which was the sun's disc placed between two mountains. Sometimes the lions were depicted as being covered with leopard-like spots, leading some to think it a depiction of the extinct Barbary lion, which, unlike African species, had a spotted coat.

Since the horizon was where night became day, Aker was said to guard the entrance and exit to the underworld, opening them for the sun to pass through during the night. As the guard, it was said that the dead had to request Aker to open the underworld's gates, so that they might enter. Also, as all who had died had to pass Aker, it was said that Aker annulled the causes of death, such as extracting the poison from any snakes that had bitten the deceased, or from any scorpions that had stung them.

As the Egyptians believed that the gates of the morning and evening were guarded by Aker, they sometimes placed twin statues of lions at the doors of their palaces and tombs. This was to guard the households and tombs from evil spirits and other malevolent beings. This practice was adopted by the Greeks and Romans, and is still unknowingly followed by some today. Unlike most of the other Egyptian deities, the worship of Aker remained popular well into the Greco-Roman era. Aker had no temples of his own like the main gods in the Egyptian religion, since he was more connected to the primeval concepts of the very old earth powers.

See also

Tem may refer to:

- Tem, Tajikistan, a small town just outside Khorugh in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province

- Tem (Togo tribe), a tribe in the African country Togo living around Sokodé

- Tem another name for Atum, an Egyptian deity

- Tem, an ancient Egyptian queen consort

| Pyramid of Teti | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Teti | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 북위 29° 52′ 31″ 동경 31° 13′ 18″ / 북위 29.87528° 동경 31.22167° | ||||||||||||||

| Ancient Name |

Ḏd-jswt-Ttj Djed-isut-Teti Teti's Places Are Enduring | ||||||||||||||

| Type | Smooth-sided Pyramid | ||||||||||||||

| Height | 100 cubits (45.72 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Base | 150 cubits (68.58 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Slope | 53° 07' 48" | ||||||||||||||

The Pyramid of Teti is a smooth-sided pyramid situated in the pyramid field at Saqqara in Egypt. It is historically the second known pyramid containing pyramid texts. Excavations have revealed a satellite pyramid, two pyramids of queens accompanied by cult structures, and a funerary temple. The pyramid was opened by Gaston Maspero in 1882 and the complex explored during several campaigns ranging from 1907 to 1965.[77] It was originally called Teti's Places Are Enduring. The preservation above ground is very poor, and it now resembles a small hill. Below ground the chambers and corridors are very well preserved.

The Funerary Complex

The pyramid complex of Teti follows a model established during the reign of Djedkare Isesi, the arrangement of which is inherited from the funerary complexes of Abusir.

A valley temple, now lost, was probably destroyed in antiquity due to the place of an Old Kingdom temple dedicated to Anubis constructed there. A better known funerary temple revealed by James Edward Quibell in 1906, is connected to the valley temple by a causeway. The plan of the temple of Teti is also comparable in many respects to that of Unas, which is its immediate predecessor. Teti's temple has a somewhat special plan, however, due to a deviation of the floor which traditionally should have been located in the axis of the temple but here is moved south.[78] It then accesses the temple through a hallway of the north-south facade joining the east-west axis of the monument. Followed in this main axis is a second hall. The thickness of the walls suggests a vaulted cover. It was probably the Room of the Greats, on the walls of which the royal family and influential members of the court were to be represented assisting and accompanying the eternal journey of their sovereign.

This hall opened into an open courtyard surrounded on all four sides by colonnades whose main purpose was the presentation of daily offerings and ritual libations. The only way out is centered to the west and provides access to the innermost part the sanctuary.

Included in the Peribolos, a sacred part of the royal pyramid reserved for priests of the king, was a chapel containing the five Naos, housing five statues of the King appearing in the aspect of the five principal deities of the realm. This part also included a private room containing the false door stela of the King, a veritable object of funeral worship, and a double row of stores on both sides of the axis of the temple. The first row frames the party host and is accessible by a long corridor along the entire width of the building that leads to the south and north within the peribolos of the pyramid. The second set frames the sanctuary and the hall of statues of gods and was only accessible from the latter.

Finally the last element essential to the funerary cult, the satellite-pyramid encircled in its own peribolos, is located southeast of the royal pyramid and therefore was accessible only through a corridor of stores and halls of worship. This small pyramid covers an underground plan consisting of a short ramp leading to a single underground chamber. In the middle of the courtyard of the paribolos, facing east and west, are two landscaped basins in the granite floor. Their use is disputed by Egyptologists, but the location of these basins, following the path of the sun, suggests ritual practices that shed some light on the role of this monument.

The Pyramid

The orientation of the pyramid is not aligned with the four cardinal points. However, the proportions and plan of the pyramid follow exactly the same pattern as that of the Pyramid of Djedkare-Isesi. The internal dimensions and slope are the same and it is otherwise very similar.

Access to the burial chambers are located inside the adjoining chapel against the north face of the pyramid. The entrance hallway leads to a long descent of eighteen hundred and twenty-three metres. The entrance was once blocked by a plug of granite now lost. The descending passage was probably clogged along its length by large blocks of limestone that thieves have broken up. The debris still littered the passage at the time of discovery. In the descending corridor is a successive horizontal hallway, a vestibule, another hallway, a bedroom with harrows, a final corridor, and a final granite passage which opens into the funerary apartments of the King.

The room with harrows spans more than six metres and is designed with alternating limestone and granite. The three granite harrows, originally lowered, are now broken into several pieces leaving the way open to visitors.

The horizontal passage leads to rooms consisting of a funeral serdab, an antechamber, and a burial chamber. All three are aligned along an east-west axis. The only peculiarity of the serdab is the size of the block ensuring its coverage, measuring 6.72 metres long with a weight of forty tons. The antechamber and burial chamber are covered with huge vaulted rafters. They are connected by a passage where access was closed by a double door. The walls of these rooms are covered with inscriptions commonly called Pyramid Texts. The pyramid of Teti is the second royal monument to contain the complex theological corpus to assist and support the rebirth of the king.

The burial chamber contains an unfinished greywacke sarcophagus, a fragment of a lid and a canopic container that is nothing more than a simple hole in the ground. And for the first time, a royal sarcophagus contains inscriptions, here slightly etched on the hollow interior of the vessel.

Although looted since ancient times, remains of the king's grave goods were found during the first excavation of the monument. Consisting mainly of stone materials, these objects have been abandoned by looters, probably considered useless or worthless. Thus, a series of club heads with the names of Teti has reached us and one of the canopic jars containing the viscera of the king. The most troubling item found among the debris of the funeral viaticum is the plaster mold of a death mask. The reproduced molding transmits to us the face of a man with eyes closed, mouth slightly open. The expression is striking and it is purported to be an image of Teti making it the only true royal portrait that has survived from the Old Kingdom. The Egyptian Royal Cubit is estimated at 525mm. Teti's pyramid measures 78.5 per side at the base and the height is 52.5m. These are equal to 150 cubits per side at the base and 100 cubits high. The core was a built in steps and accretions made of small, locally quarried stone and debris fill.[79] This was covered with a layer of dressed limestone which has been removed, causing the core to slump

Photos

-

Sarcophagus of Teti

-

Engraved texts of the Burial Chamber

-

Another view of the Pyramid Texts in the antechamber of the pyramid of Teti

-

Detail with the cartouche of Teti

The Necropolis of Teti

All around the funerary complex of the king extends one of the richest parts of the necropolis of Saqqara. The king, whose special destiny seems to have impressed his contemporaries, will be revered later as a divine mediator along with a few courtiers who have in some sense inherited it by reputation. The king was also accompanied by his two principal wives who each had a pyramid accompanied with a temple of worship.

Among the many tombs that form this necropolis of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt include:

- The pyramid complex of Khuit II;

- The pyramid complex of Iput I;

- The pyramid complex of Sesheshet I, the king's mother;

- The mastaba of Tetiankh Khem, royal prince, son of Teti and Khouit;

- The mastaba of Kagemni, Vizier of Teti;

- The mastaba of Ankhmahor;

- The mastaba of Mereruka.

Menkauhor Kaiu, a pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty built his pyramid and is one of the predecessors near Teti's pyramid.

During the Middle Kingdom, the cult of the king was assured as evidenced by recent discoveries in the east of Teti's pyramid tombs of Sa-Hathor-Ipy Sekoueskhet and two priests attached to the worship of the famous pharaoh.[80]

In the New Kingdom, other graves are arranged near the funerary complex of Teti, who is sometimes referred to as a true deity. Under the reign of Ramses II, Khaemwaset, the royal prince and High Priest of Ptah, would even restore the pyramid of the distant ruler, taking care to re-register his name on one side of his pyramid.

Finally, in the Late Period, popular enthusiasm for the gods of Saqqara increased to the point that a temple dedicated to Anubis is built on the funerary complex of Teti whose pyramid continued to dominate the entire valley and would remain a sacred monument to all the devotees who borrowed while along dromos leading to the Serapeum of Saqqara and which skirted the venerable pyramid of Teti.

See also

References

Work cited in the text

- David P. Silverman, Middle Kingdom tombs in the Teti pyramid cemetery, Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000, Praque, 2000

Other articles

- Cecil Mallaby Firth, The Teti pyramid cemeteries, Excavations at Saqqara, Egyptian Department of Antiquities, Cairo, 1926;

- Jean-Philippe Lauer & Jean Leclant, Le temple haut du complexe funéraire du roi Téti, Bulletin d'Études n°51, 1972;

- Sydney Aufrère & Jean-Claude Golvin, L'Égypte restituée, 1997;

- Jean-Pierre Adam & Christiane Ziegler, Les pyramides d'Égypte, 1999;

- Audran Labrousse, L'architecture des pyramides à textes, 2000.

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

| Ancient Egypt portal |

The ancient Egyptians believed that a human soul was made up of five parts: the Ren, the Ba, the Ka, the Sheut, and the Ib. In addition to these components of the soul there was the human body (called the ha, occasionally a plural haw, meaning approximately sum of bodily parts). The other souls were aakhu, khaibut, and khat.

Ib (heart)

| ||

| jb (F34) "heart" | ||

|---|---|---|

| 신성문자 표기 |

An important part of the Egyptian soul was thought to be the Ib (jb), or heart. The Ib[81] or metaphysical heart was believed to be formed from one drop of blood from the child's mother's heart, taken at conception.[82]

To ancient Egyptians, the heart was the seat of emotion, thought, will and intention. This is evidenced by the many expressions in the Egyptian language which incorporate the word ib, Awt-ib: happiness (literally, wideness of heart), Xak-ib: estranged (literally, truncated of heart). This word was transcribed by Wallis Budge as Ab.

In Egyptian religion, the heart was the key to the afterlife. It was conceived as surviving death in the nether world, where it gave evidence for, or against, its possessor. It was thought that the heart was examined by Anubis and the deities during the Weighing of the Heart ceremony. If the heart weighed more than the feather of Maat, it was immediately consumed by the monster Ammit.

Sheut (shadow)

A person's shadow, Sheut (šwt in Egyptian), is always present. Because of this, Egyptians surmised that a shadow contains something of the person it represents. Through this association, statues of people and deities were sometimes referred to as shadows.

The shadow was also representative to Egyptians of a figure of death, or servant of Anubis, and was depicted graphically as a small human figure painted completely black.

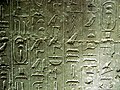

Ren (name)

As a part of the soul, a person's ren (rn 'name') was given to them at birth and the Egyptians believed that it would live for as long as that name was spoken, which explains why efforts were made to protect it and the practice of placing it in numerous writings. For example, part of the Book of Breathings, a derivative of the Book of the Dead, was a means to ensure the survival of the name. A cartouche (magical rope) often was used to surround the name and protect it. Conversely, the names of deceased enemies of the state, such as Akhenaten, were hacked out of monuments in a form of damnatio memoriae. Sometimes, however, they were removed in order to make room for the economical insertion of the name of a successor, without having to build another monument. The greater the number of places a name was used, the greater the possibility it would survive to be read and spoken.

Ba

| ||

| bꜣ (G29) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 신성문자 표기 |

| ||

| bꜣ (G53) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 신성문자 표기 |

The 'Ba' (bꜣ) was everything that makes an individual unique, similar to the notion of 'personality'. (In this sense, inanimate objects could also have a 'Ba', a unique character, and indeed Old Kingdom pyramids often were called the 'Ba' of their owner). The 'Ba' is an aspect of a person that the Egyptians believed would live after the body died, and it is sometimes depicted as a human-headed bird flying out of the tomb to join with the 'Ka' in the afterlife.

In the Coffin Texts one form of the Ba that comes into existence after death is corporeal, eating, drinking and copulating. Louis Žabkar argued that the Ba is not part of the person but is the person himself, unlike the soul in Greek, or late Judaic, Christian or Muslim thought. The idea of a purely immaterial existence was so foreign to Egyptian thought that when Christianity spread in Egypt they borrowed the Greek word psyche to describe the concept of soul and not the term Ba. Žabkar concludes that so particular was the concept of Ba to ancient Egyptian thought that it ought not to be translated but instead the concept be footnoted or parenthetically explained as one of the modes of existence for a person.[83]

In another mode of existence the Ba of the deceased is depicted in the Book of Going Forth by Day returning to the mummy and participating in life outside the tomb in non-corporeal form, echoing the solar theology of Re (or Ra) uniting with Osiris each night.[84]

The word 'bau' (bꜣw), plural of the word ba, meant something similar to 'impressiveness', 'power', and 'reputation', particularly of a deity. When a deity intervened in human affairs, it was said that the 'Bau' of the deity were at work [Borghouts 1982]. In this regard, the ruler was regarded as a 'Ba' of a deity, or one deity was believed to be the 'Ba' of another.

Ka

| ||

| kꜣ (D28) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 신성문자 표기 |

The Ka (kꜣ) was the Egyptian concept of vital essence, that which distinguishes the difference between a living and a dead person, with death occurring when the ka left the body. The Egyptians believed that Khnum created the bodies of children on a potter's wheel and inserted them into their mothers' bodies. Depending on the region, Egyptians believed that Heket or Meskhenet was the creator of each person's Ka, breathing it into them at the instant of their birth as the part of their soul that made them be alive. This resembles the concept of spirit in other religions.

The Egyptians also believed that the ka was sustained through food and drink. For this reason food and drink offerings were presented to the dead, although it was the kau (kꜣw) within the offerings that was consumed, not the physical aspect. The ka was often represented in Egyptian iconography as a second image of the king, leading earlier works to attempt to translate ka as double.

Akh

The Akh (Ꜣḫ meaning '(magically) effective one'),[85] was a concept of the dead that varied over the long history of ancient Egyptian belief.

It was associated with thought, but not as an action of the mind; rather, it was intellect as a living entity. The Akh also played a role in the afterlife. Following the death of the Khat, the Ba and Ka were reunited to reanimate the Akh.[86] The reanimation of the Akh was only possible if the proper funeral rites were executed and followed by constant offerings. The ritual was termed: se-akh 'to make (a dead person) into an (living) akh.' In this sense, it even developed into a sort of ghost or roaming 'dead being' (when the tomb was not in order any more) during the Ramesside Period. An Akh could do either harm or good to persons still living, depending on the circumstances, causing e.g., nightmares, feelings of guilt, sickness, etc. It could be evoked by prayers or written letters left in the tomb's offering chapel also in order to help living family members, e.g., by intervening in disputes, by making an appeal to other dead persons or deities with any authority to influence things on earth for the better, but also to inflict punishments.

The separation of Akh and the unification of Ka and Ba were brought about after death by having the proper offerings made and knowing the proper, efficacious spell, but there was an attendant risk of dying again. Egyptian funerary literature (such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead) were intended to aid the deceased in "not dying a second time" and becoming an akh.

Relationships

Ancient Egyptians believed that death occurs when a person's ka leaves the body. Ceremonies conducted by priests after death, including the "opening of the mouth (wp r)", aimed not only to restore a person's physical abilities in death, but also to release a Ba's attachment to the body. This allowed the Ba to be united with the Ka in the afterlife, creating an entity known as an "Akh" (ꜣḫ, meaning "effective one").

Egyptians conceived of an afterlife as quite similar to normal physical existence — but with a difference. The model for this new existence was the journey of the Sun. At night the Sun descended into the Duat (the underworld). Eventually the Sun meets the body of the mummified Osiris. Osiris and the Sun, re-energized by each other, rise to new life for another day. For the deceased, their body and their tomb were their personal Osiris and a personal Duat. For this reason they are often addressed as "Osiris". For this process to work, some sort of bodily preservation was required, to allow the Ba to return during the night, and to rise to new life in the morning. However, the complete Akhu were also thought to appear as stars.[87] Until the Late Period, non-royal Egyptians did not expect to unite with the Sun deity, it being reserved for the royals.[88]

The Book of the Dead, the collection of spells which aided a person in the afterlife, had the Egyptian name of the Book of going forth by day. They helped people avoid the perils of the afterlife and also aided their existence, containing spells to assure "not dying a second time in the underworld", and to "grant memory always" to a person. In the Egyptian religion it was possible to die in the afterlife and this death was permanent.

The tomb of Paheri, an Eighteenth dynasty nomarch of Nekhen, has an eloquent description of this existence, and is translated by James P. Allen as:

Your life happening again, without your ba being kept away from your divine corpse, with your ba being together with the akh ... You shall emerge each day and return each evening. A lamp will be lit for you in the night until the sunlight shines forth on your breast. You shall be told: "Welcome, welcome, into this your house of the living!"

See also

References

- Wisner, Kerry E. (2001), http://www.hwt-hrw.com/Bodies.php, 2011년 3월 3일에 확인함

|제목=이(가) 없거나 비었음 (도움말) - EGYPTOLOGY ONLINE (2001), http://web.archive.org/web/20080421124839re_/www.egyptologyonline.com/the_afterlife.htm, 2008년 4월 21일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서, 2009에 확인함

|제목=이(가) 없거나 비었음 (도움말)

Further reading

- Allen, James Paul. 2001. "Ba". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 1 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 161–162.

- Allen, James P. 2000. "Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs", Cambridge University Press.

- Borghouts, Joris Frans. 1982. "Divine Intervention in Ancient Egypt and Its Manifestation (b3w)". In Gleanings from Deir el-Medîna, edited by Robert Johannes Demarée and Jacobus Johannes Janssen. Egyptologische Uitgaven 1. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. 1–70.

- Borioni, Giacomo C. 2005. "Der Ka aus religionswissenschaftlicher Sicht", Veröffentlichungen der Institute für Afrikanistik und Ägyptologie der Universität Wien.

- Burroughs, William S. 1987. "The Western Lands", Viking Press. (fiction).

- Friedman, Florence Margaret Dunn. 1981. On the Meaning of Akh (3ḫ) in Egyptian Mortuary Texts. Doctoral dissertation; Waltham: Brandeis University, Department of Classical and Oriental Studies.

- ———. 2001. "Akh". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 1 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 47–48.

- Jaynes, Julian. 1976. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, Princeton University.

- Žabkar, Louis Vico. 1968. A Study of the Ba Concept in Ancient Egyptian Texts. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 34. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Unȧs 피라미드 텍스트 (1)의 해석

[편집]| Aker in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

ꜣkr | ||||

| ||||

From this paragraph we see that Unȧs is declared to be the son of Tem, and has made himself stronger than his father, and that when the king, who lives upon his fathers and mothers, enters the sky as a god, all creation is smitten with terror. The sky dissolves in rain, the stars shake in their places, and even the bones of the great double lion-headed earth-god Aker, [Gods1 49], quake (전율하다), and all the lesser powers of heaven flee in fear.

He is considered to have been a mighty conqueror upon earth, for those whom he has vanquished are [Page 34] beneath his feet; there is no reason why this statement should not be taken literally, and not as referring to the mere pictures of enemies which were sometimes painted on the cartonnage (고대 이집트 미라의 관) coverings of mummies under the feet, and upon the sandals of mummies, and upon the outside of the feet of coffins.

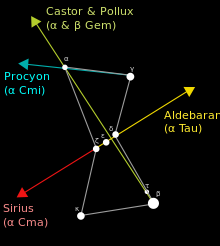

An ordinary man possessed one ka or “double,” but a king or a god was believed to possess many kau or “doubles.” Thus in one text22) the god Rā is said to possess seven souls (bau) and fourteen doubles (kau), and prayers were addressed to each soul and double of Rā as well as to the god himself; elsewhere23) we are told that the fourteen kau of Rā, [Gods1 50], were given to him by Thoth.

22) Dümichen, Tempelinschriſten, vol. i., pi. 29.

23) Lepsius, Denkmäler, iii., Bl. 194.

Unȧs appears in heaven with his “gods” upon him, the serpents are on his brow, he is led by a serpent-guide, and is endowed with his powers. It is difficult to say what the “gods” here referred to really are, for it is unlikely that the allusion is to the small figures of gods which, in later times, were laid upon the bodies of the dead, and it seems that we are to understand that he, Unȧs, was accompanied by a number of divine beings who had laid their protecting strength upon him. The uraei on his brow and his serpent-guide were the emblems of similar beings whose help he had bespoken (보여주다; 시사하다)—in other words, they represented spirits of serpents which were made friendly towards man.

Unȧs 피라미드 텍스트 (2)

[편집]The passage in the text of Unȧs continues,

- “Unȧs is the Bull of heaven which overcometh by his will, and which feedeth upon that which cometh into being from every god, and he eateth of the provender (여물) of those who fill themselves with words of power and come from the Lake of Flame.

- Unȧs is provided with power sufficient to resist his spirits (khu), and he riseth [in heaven] like a mighty god who is the lord of the seat of the hand (i.e., power) [of the gods].

- He taketh his seat and his back is towards Seb. Unȧs weigheth his speech with the god whose name is hidden on the day of slaughtering the oldest [gods].

- Unȧs is the master of the offering and he tieth the knot, and provideth meals for himself; he eateth men and he [Page 35] liveth upon gods, he is the lord of offerings, and he keepeth count of the lists of the same.”

The ancient Egyptians believed that a human soul was made up of five parts: the Ren, the Ba, the Ka, the Sheut, and the Ib. In addition to these components of the soul there was the human body (called the ha, occasionally a plural haw, meaning approximately sum of bodily parts). The other souls were aakhu, khaibut, and khat.

Ka

| ||

| kꜣ (D28) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 신성문자 표기 |

The Ka (kꜣ) was the Egyptian concept of vital essence, that which distinguishes the difference between a living and a dead person, with death occurring when the ka left the body. The Egyptians believed that Khnum created the bodies of children on a potter's wheel and inserted them into their mothers' bodies. Depending on the region, Egyptians believed that Heket or Meskhenet was the creator of each person's Ka, breathing it into them at the instant of their birth as the part of their soul that made them be alive. This resembles the concept of spirit in other religions.

The Egyptians also believed that the ka was sustained through food and drink. For this reason food and drink offerings were presented to the dead, although it was the kau (kꜣw) within the offerings that was consumed, not the physical aspect. The ka was often represented in Egyptian iconography as a second image of the king, leading earlier works to attempt to translate ka as double.

Unȧs 피라미드 텍스트 (2)의 해석

[편집]Unȧs의 음식

[편집]The dead king (즉 Unȧs) is next likened to a young and vigorous bull which feeds upon what is produced by every god and upon those that come from theFiery Lake to eat words of power. Here we have a survival of the old worship of the bull, which began in the earliest times in Egypt, and lasted until the Roman period. His food is that which is produced by every god, and when we remember that the Egyptians believed that every object, animate and inanimate, was the habitation of a spirit or god, it is easy to see that the allusion in these words is to the green herbage (목초) which the bull ordinarily eats, for from this point of view, every blade of grass was the abode of a god.

In connexion with this may be quoted the words of Sankhôn-yâthân, the Sanchoniatho of the Greeks, as given by Eusebius, who says,

- “But these first men consecrated the productions of the earth, and judged them gods, and worshipped those things, upon which they themselves lived, and all their posterity, and all before them; to these they made libations and sacrifices.” 24)

24) Eusebius, Praep. Evan., lib. i., c. 10 (in Cory, Ancient Fragments, London, 1832, p. 5).

Sanchuniathon (Greek: Σαγχουνιάθων; gen.: Σαγχουνιάθωνος) is the purported Phoenician author of three lost works originally in the Phoenician language, surviving only in partial paraphrase and summary of a Greek translation by Philo of Byblos, according to the Christian bishop Eusebius of Caesarea. These few fragments comprise the most extended literary source concerning Phoenician religion in either Greek or Latin: Phoenician sources, along with all of Phoenician literature, were lost with the parchment on which they were habitually written. He is also known as Sancuniates.

The author

The compilers of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica warned that Sanchuniathon "belongs more to legend than to history." All our knowledge of Sanchuniathon and his work comes from Eusebius's Praeparatio Evangelica, (I. chs ix-x)[90] which contains some information about him along with the only surviving excerpts from his writing, as summarized and quoted from his supposed translator, Philo of Byblos.

Eusebius also quotes the neo-Platonist writer Porphyry as stating that Sanchuniathon of Berytus (Beirut) wrote the truest history about the Jews because he obtained records from "Hierombalus" ("Jerubbaal"? or "Hiram'baal" ?) priest of the god Ieuo (Yahweh), that Sanchuniathon dedicated his history to Abibalus king of Berytus, and that it was approved by the king and other investigators, the date of this writing being before the Trojan war[91] approaching close to the time of Moses, "when Semiramis was queen of the Assyrians."[92] Thus Sanchuniathon is placed firmly in the mythic context of the pre-Homeric heroic age, an antiquity from which no other Greek or Phoenician writings are known to have survived to the time of Philo. Curiously, however, he is made to refer disparagingly to Hesiod at one point, who lived in Greece ca. 700 BC.

The supposed Sanchuniathon claimed to have based his work on "collections of secret writings of the Ammouneis[93] discovered in the shrines", sacred lore deciphered from mystic inscriptions on the pillars which stood in the Phoenician temples, lore which exposed the truth—later covered up by invented allegories and myths—that the gods were originally human beings who came to be worshipped after their deaths and that the Phoenicians had taken what were originally names of their kings and applied them to elements of the cosmos (compare euhemerism) as well as also worshipping forces of nature and the sun, moon, and stars. Eusebius' intent in mentioning Sanchuniathon is to discredit pagan religion based on such foundations.

This rationalizing euhemeristic slant and the emphasis on Beirut, a city of great importance in the late classical period but apparently of little importance in ancient times, suggests that the work itself is not nearly as old as it claims to be. Some have suggested it was forged by Philo of Byblos himself, or assembled from various traditions and presented within an authenticating pseudepigraphical format, in order to give the material more believable weight. Or Philo may have translated genuine Phoenician works ascribed to an ancient writer known as Sanchuniathon, but in fact written in more recent times.

Not all readers have taken such a critical view. Squier Payne remarked in a preface to Richard Cumberland's Sanchoniatho's Phoenician History (1720)

- "The Humour which prevail'd with several learned Men to reject Sanchuniatho as a counterfeit because they knew not what to make of him, his Lordship always blam'd Philo Byblius, Porphyry and Eusebius, who were better able to judge than any Moderns, never call in question his being genuine."[94]

However that may be,[95] much of what has been preserved in this writing, despite the euhemeristic interpretation given it, turned out to be supported by the Ugaritic mythological texts excavated at Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit) in Syria since 1929; Otto Eissfeldt demonstrated in 1952[96] that it does incorporate genuine Semitic elements that can now be related to the Ugaritic texts, some of which is shown in our versions of Sanchuniathon, remained unchanged since the second millennium BC. The modern consensus is that Philo's treatment of Sanchuniathon offered a Hellenistic view of Phoenician materials[97] written between the time of Alexander the Great and the first century BC, if it was not a literary invention of Philo.[98]

In what follows, it is sometimes difficult to tell whether Eusebius is citing Philo's translation of Sanchuniathon or speaking in his own voice. Another difficulty is the use of Greek proper names instead of Phoenician ones and the possible corruption of some of the Phoenician names that do appear. There may be other garblings.

The work

The fragments that come down to us contain: Philosophical creation story

A philosophical creation story traced to "the cosmogony of Taautus, whom Philo explicitly identified with the Egyptian Thoth—"the first who thought of the invention of letters, and began the writing of records"— which begins with Erebus and Wind, between which Eros 'Desire' came to be. From this was produced Môt which seems to be the Phoenician/Ge'ez/Hebrew/Arabic/Ancient Egyptian word for 'Death' but which the account says may mean 'mud'. In a mixed confusion, the germs of life appear, and intelligent animals called Zophasemin (explained probably correctly as 'observers of heaven') formed together as an egg, perhaps. The account is not clear. Then Môt burst forth into light and the heavens were created and the various elements found their stations.

Following the etymological line of Jacob Bryant one might also consider with regard to the meaning of Môt, that according to the Ancient Egyptians Ma'at was the personification of the fundamental order of the universe, without which all of creation would perish. She was also considered the wife of Thoth.

Allegorical culture heroes

Copias and his wife Baau (translated as Nyx 'Night') give birth to Aeon and Protogonus ("first-born"), who are mortal men; "and that when droughts occurred, they stretched out their hands to heaven towards the sun; for him alone (he says) they regarded as god the lord of heaven, calling him Beelsamen, which is in the Phoenician language 'lord of heaven,' and in Greek 'Zeus.'" (Eusebius, I, x). A race of Titan-like mountain beings arose, "sons of surpassing size and stature, whose names were applied to the mountains which they occupied... and they got their names, he says, from their mothers, as the women in those days had free intercourse with any whom they met." Various descendants are listed, many of whom have allegorical names but are described in the quotations from Philo as mortals who first made particular discoveries or who established particular customs.

The history of the gods

Then comes a genealogy and history of various northwest Semitic gods who were widely worshipped, sometimes hidden under Greek names. Greek names appear below in parentheses and italics. Only equations made in the text appear here but many of the hyperlinks point to the northwest Semitic deity that is probably intended.

Elioun = Beruth (Hypsistus)| | +-------+------+ | | | | (Uranus)/(Epigeius) = (Ge) (Autochthon) | | +-----------+------------------------------+-----------+--------+----------------+-------+ | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Elus Baetylus (Uranus) = ? = Dagon/(Siton) (Atlas) Astarte = Elus = (Rhea) Baaltis (Cronus) | (Zeus Arotrios) (Aphrodite)| | (Dione) | | | | +-----------+--------+ | +++++++-------+-------+-+ +++++++----+ | | | | ||||||| | | ||||||| | | | | | ||||||| | | ||||||| | (Persephone) (Athena) (Sadidus) Demarûs Sydyc = (Titanides) (Pothos) (Eros) 7 sons Muth Adodus/(Zeus) | | (Artemides) (Qetesh) (Thanatos) | | | (Pluto) +------+ +++++++ +------+ | ||||||| | | ||||||| | Melcarthus (Cabeiri) (Asclepius) (Heracles) (Corybantes) (Samothraces) (Dioscuri)

Elus = Anobret (Nereus) born in Peraea | | | | | | +---------------+------------+ +----+ | | | | | | | | | | | (Cronus II) (Zeus) Belus (Apollo) Iedud (Pontus) Mot | | | | | | Sidon

Translations of Greek forms: arotrios, 'of husbandry, farming'; autochthon (for autokhthon) 'produced from the ground', epigeius (for epigeios) 'from the earth', eros 'desire', ge 'earth', hypsistos 'most high', pluto (for plouton) 'wealthy', pontus (for pontos) 'sea', pothos 'longing', siton 'grain', thanatos 'death', uranus (for ouranos) 'sky'.

As in the Greek and Hittite theogonies, Sanchuniathon's Elus/Cronus overthrows his father Sky or Uranus and castrates him. However Zeus Demarûs, that is Hadad Ramman, purported son of Dagon but actually son of Uranus, eventually joins with Uranus and wages war against Cronus. To El/Cronus is attributed the practice of circumcision. Twice we are told that El/Cronus sacrificed his own son. At some point peace is made and Zeus Adados (Hadad) and Astarte reign over the land with Cronus' permission. An account of the events is written by the Cabeiri and by Asclepius, under Thoth's direction.

About serpents