사용자:배우는사람/문서:Nimrod 1.1 (1-16) - Orion

ORION[편집]

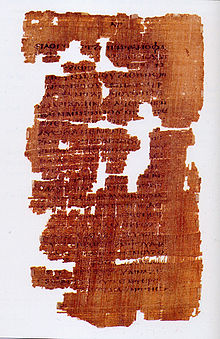

[Page 1] [PDF Page 16]

로마 시대에 많은 저술가들 야만인의 문헌에서 이교도의 수수께끼의 열쇠를 발견하였다[편집]

[Page 1] [S. I.] THE elder Greek writers, being ignorant themselves of the real meaning of their Theogonies, Heroogonies, and pretended (가짜[상상]의) ancient Histories, were of course unable to furnish us with any sufficient explanation of them. But in later times of what still must be called antiquity, when the united empire of the Greeks and Latins extended from the Rhine and Danube to Euphrates and the Thebais, many writers having access to other and, what were sometimes called, barbarous sources, discovered in them the keys to many riddles of paganism ;

The Thebaid or Thebais (Θηβαΐδα, Thēbaïda or Θηβαΐς, Thēbaïs) is the region of ancient Egypt containing the thirteen southernmost nomes of Upper Egypt, from Abydos to Aswan. It acquired its name from its proximity to the ancient Egyptian capital of Thebes.

In Ptolemaic Egypt, the Thebaid formed a single administrative district under the Epistrategos of Thebes, who was also responsible for overseeing navigation in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

During the Roman Empire, Diocletian created the province of Thebais, guarded by the legions I Maximiana Thebanorum and II Flavia Constantia. This was later divided into Upper (Thebais Superior, Ἄνω Θηβαΐς, Anō Thēbaïs), comprising the southern half with its capital at Thebes, and Lower or Nearer (Thebais Inferior, Θηβαΐς Ἐγγίστη, Thēbaïs Engistē), comprising the northern half with capital at Ptolemais.

Around the 5th century, since it was a desert, the Thebaid became a place of retreat of a number of Christian hermits, and was the birthplace of Pachomius.[1] In Christian art, the Thebaid was represented as a place with numerous monks.

이러한 저술가들이 권위자가 되었다[편집]

and these men, grammarians, sophists, fathers of the church, and various others, immeasurably (헤아릴 수 없을 정도로) as (~에도 불구하고) they may fall short of (~에 미치지 못하다) antique genius and acumen (감각), became in many things, by reason of the increase of positive (확실한, 분명한, 결정적인) knowledge, more useful authorities than even the greatest of the writers who went before them: not to say that their works comprehend (포괄하다, 충분히 이해하다), either avowedly (명백히), or by necessary (필연적인) inference, the contents of many truly ancient works, to which we have no access.

Macedonian dynasties 와 Roman governments 아래의 그리스의 학문[편집]

The literature of the Greeks began to enlarge its field, and to rifle (샅샅이 뒤지다) the unexplored treasures of the original East, under the Macedonian dynasties ; and the like investigation, carried on under the Roman governments, has not yet nearly arrived at its completion.

And so far from (…라기보다는 반대로) deserving rebuke (비난), we do but follow the light of human learning as it opens to our view, when we at times consult omnia omnium1) hominum et temporum commenta (= [구글 번역] all men of all times and the comments), and endeavour from such sources to improve and enlarge the circumscribed (제한[억제]하다) views of the mighty dead, [Page2] gravissimorum hominum Thucydidis et Aristotelis (= [구글 번역] most impressive of Thucydides and Aristotle).

1) V. Payne, Knight Proleg, s. 53.

Thucydides (/θjuːˈsɪd[미지원 입력]diːz/; Θουκυδίδης, Thoukydídēs; c. 460 – c. 395 BC) was a Greek historian and Athenian general. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientific history", because of his strict standards of evidence-gathering and analysis in terms of cause and effect without reference to intervention by the gods, as outlined in his introduction to his work.[2]

He has also been called the father of the school of political realism, which views the relations between nations as based on might rather than right.[3] His text is still studied at advanced military colleges worldwide, and the Melian dialogue remains a seminal work of international relations theory.

More generally, Thucydides showed an interest in developing an understanding of human nature to explain behaviour in such crises as plague, massacres, as in that of the Melians, and civil war.

Thucydides versus Herodotus

Thucydides (c. 460 – c. 395 BC) and his immediate predecessor Herodotus (c. 484–425 BC) both exerted a significant influence on Western historiography. Thucydides does not mention his counterpart by name, but his famous introductory statement is thought to refer to him:[4][5]

| “ | To hear this history rehearsed, for that there be inserted in it no fables, shall be perhaps not delightful. But he that desires to look into the truth of things done, and which (according to the condition of humanity) may be done again, or at least their like, shall find enough herein to make him think it profitable. And it is compiled rather for an everlasting possession than to be rehearsed for a prize. | ” |

Herodotus records in his Histories not only the events of the Persian Wars but also geographical and ethnographical information, as well as the fables related to him during his extensive travels. Typically, he passes no definitive judgment on what he has heard. In the case of conflicting or unlikely accounts, he presents both sides, says what he believes and then invites readers to decide for themselves.[6] The work of Herodotus is reported to have been recited at festivals, where prizes were awarded, as for example, during the games at Olympia.[7]

Herodotus views history as a source of moral lessons, with conflicts and wars as misfortunes flowing from initial acts of injustice perpetuated through cycles of revenge.[8] In contrast, Thucydides claims to confine himself to factual reports of contemporary political and military events, based on unambiguous, first-hand, eye-witness accounts,[9] although, unlike Herodotus, he does not reveal his sources. Thucydides views life exclusively as political life, and history in terms of political history. Conventional moral considerations play no role in his analysis of political events while geographic and ethnographic aspects are omitted or, at best, of secondary importance. Subsequent Greek historians — such as Ctesias, Diodorus, Strabo, Polybius and Plutarch — held up Thucydides' writings as a model of truthful history. Lucian[10] refers to Thucydides as having given Greek historians their law, requiring them to say what had been done (ὡς ἐπράχθη). Greek historians of the fourth century BC accepted that history was political and that contemporary history was the proper domain of a historian.[11] Cicero calls Herodotus the "father of history;"[12] yet the Greek writer Plutarch, in his Moralia (Ethics) denigrated Herodotus, as the "father of lies".[13] Unlike Thucydides, however, these historians all continued to view history as a source of moral lessons.

Due to the loss of the ability to read Greek, Thucydides and Herodotus were largely forgotten during the Middle Ages in Western Europe, although their influence continued in the Byzantine world. In Europe, Herodotus become known and highly respected only in the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth century as an ethnographer, in part due to the discovery of America, where customs and animals were encountered even more surprising than what he had related. During the Reformation, moreover, information about Middle Eastern countries in the Histories provided a basis for establishing Biblical chronology as advocated by Isaac Newton.

The first European translation of Thucydides (into Latin) was made by the humanist Lorenzo Valla between 1448 and 1452, and the first Greek edition was published by Aldo Manunzio in 1502. During the Renaissance, however, Thucydides attracted less interest among Western European historians as a political philosopher than his successor, Polybius,[14] although Poggio Bracciolini claimed to have been influenced by him. There is not much trace of Thucydides' influence in Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince (1513), which held that the chief aim of a new prince must be to "maintain his state" [i.e., his power] and that in so doing he is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion. Later historians, such as J. B. Bury, however, have noted parallels between them:In the seventeenth century, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose Leviathan advocated absolute monarchy, admired Thucydides and in 1628 was the first to translate his writings into English directly from Greek. Thucydides, Hobbes and Machiavelli are together considered the founding fathers of political realism, according to which state policy must primarily or solely focus on the need to maintain military and economic power rather than on ideals or ethics. Nineteenth-century positivist historians stressed what they saw as Thucydides' seriousness, his scientific objectivity and his advanced handling of evidence. A virtual cult following developed among such German philosophers as Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Schlegel and Friedrich Nietzsche, who claimed that, "[in Thucydides], the portrayer of man, that culture of the most impartial knowledge of the world finds its last glorious flower." For Eduard Meyer, Macaulay and Leopold von Ranke, who initiated modern source-based history writing,[16] Thucydides was again the model historian.[17][18]If, instead of a history, Thucydides had written an analytical treatise on politics, with particular reference to the Athenian empire, it is probable that . . . he could have forestalled Machiavelli. . . .[since] the whole innuendo of the Thucydidean treatment of history agrees with the fundamental postulate of Machiavelli, the supremacy of reason of state. To maintain a state said the Florentine thinker, "a statesman is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion." . . . But . . . the true Machiavelli, not the Machiavelli of fable. . . entertained an ideal: Italy for the Italians, Italy freed from the stranger: and in the service of this ideal he desired to see his speculative science of politics applied. Thucydides has no political aim in view: he was purely a historian. But it was part of the method of both alike to eliminate conventional sentiment and morality.[15]

Generals and statesmen loved him: the world he drew was theirs, an exclusive power-brokers' club. It is no accident that even today Thucydides turns up as a guiding spirit in military academies, neocon think tanks and the writings of men like Henry Kissinger; whereas Herodotus has been the choice of imaginative novelists (Michael Ondaatje's novel The English Patient and the film based on it boosted the sale of the Histories to a wholly unforeseen degree) and — as food for a starved soul — of an equally imaginative foreign correspondent from Iron Curtain Poland, Ryszard Kapuscinski.[19]

These historians also admired Herodotus, however, as social and ethnographic history increasingly came to be recognized as complementary to political history.[20] In the twentieth century, this trend gave rise to the works of Johan Huizinga, Marc Bloch and Braudel, who pioneered the study of long-term cultural and economic developments and the patterns of everyday life. The Annales School, which exemplifies this direction, has been viewed as extending the tradition of Herodotus.[21]

At the same time, Thucydides' influence was increasingly important in the area of international relations during the Cold War, through the work of Hans Morgenthau, Leo Strauss[22] and Edward Carr.[23]

The tension between the Thucydidean and Herodotean traditions extends beyond historical research. According to Irving Kristol, self-described founder of American Neoconservatism, Thucydides wrote "the favorite neoconservative text on foreign affairs";[24] and Thucydides is a required text at the Naval War College, an American institution located in Rhode Island. On the other hand, Daniel Mendelsohn, in a review of a recent edition of Herodotus, suggests that, at least in his graduate school days during the Cold War, professing admiration of Thucydides served as a form of self-presentation:

To be an admirer of Thucydides' History, with its deep cynicism about political, rhetorical and ideological hypocrisy, with its all too recognizable protagonists — a liberal yet imperialistic democracy and an authoritarian oligarchy, engaged in a war of attrition fought by proxy at the remote fringes of empire — was to advertise yourself as a hardheaded connoisseur of global Realpolitik.[25]

Another author, Thomas Geoghegan, whose speciality is labour rights, comes down on the side of Herodotus when it comes to drawing lessons relevant to Americans, who, he notes, tend to be rather isolationist in their habits (if not in their political theorizing): "We should also spend more funds to get our young people out of the library where they're reading Thucydides and get them to start living like Herodotus — going out and seeing the world."[26]

고대 전통의 분석을 위한 길이 닦였다[편집]

Mr. Bryant의 etymology 사용과 G. S. Faber의 추구[편집]

Thus was the way paved for that fuller analysis of ancient traditions, which Mr. Bryant (Jacob Bryant: 1715~1804) attempted with so large a display of learning and cleverness, however little we may respect some of his reasonings, and his general use of that formidable (가공할, 어마어마한) engine, which he misnames etymology (어원 연구).

A living divine (즉, George Stanley Faber: 1773~1854; 저자 Algernon Herbert는 1792~1855) has pursued the same path with more caution, and has added to the results obtained by Mr. Bryant such confirmation, as must for ever prevent (예방/방지) the history of the Gentiles from relapsing into complete obscurity (잊혀짐, 모호함, 어려움)2).

2) Origin of Pagan Idolatry, 3 vols. 1816.

It should be remembered that the first-named of these writers (즉, Mr. Bryant), striking out (만들다) a path for himself, or building [if you will (말하자면)] a bridge over Chaos itself, has every excuse for imperfection, and challenges (이의를 제기하다[도전하다]) admiration for what he has done ;

- [greek] O ?' iireira, [LST% \yyiat. tcuve Osoio.

| Jacob Bryant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1715 Plymouth, Devon |

| Died | 14 November 1804 (aged 88–89) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | scholar, mythographer |

Jacob Bryant (1715–1804) was a British scholar and mythographer, who has been described as "the outstanding figure among the mythagogues who flourished in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries".[27]

Life

Bryant was born at Plymouth. His father worked in the customs there, but was afterwards moved to Chatham. Bryant was first sent to a school near Rochester, and then to Eton College. In 1736 he was elected to a scholarship at King's College, Cambridge, where he took his degrees of B.A. (1740) and M.A. (1744), later being elected a fellow.[28] He returned to Eton as private tutor to the Duke of Marlborough. In 1756 he accompanied the duke, who was master-general of ordnance and commander-in-chief of the forces in Germany, to the Continent as private secretary. He was rewarded by a lucrative appointment in the ordnance department, which allowed him time to indulge his literary tastes. He was twice offered the mastership of Charterhouse school, but turned it down.

Bryant died on the 14th of November 1804 at Cippenham near Windsor. He left his library to King's College, having previously made some valuable presents from it to the king and the Duke of Marlborough. He bequeathed £2000 to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, and £1000 for the use of the retired collegers of Eton.

Works

His chief works were A New System or Analysis of Ancient Mythology[29] (1774–76, and later editions), Observations on the Plain of Troy (1795), and Dissertation concerning the Wars of Troy (1796). He also wrote on theological, political and literary subjects.

Mythographer

Bryant saw all mythology as derived from the Hebrew Scriptures, with Greek mythology arising via the Egyptians.[30] The New System attempted to link the mythologies of the world to the stories recorded in Genesis. Bryant argued that the descendents of Ham had been the most energetic, but also the most rebellious peoples of the world and had given rise to the great ancient and classical civilisations. He called these people "Amonians", because he believed that the Egyptian god Amon was a deified form of Ham. He argued that Ham had been identified with the sun, and that much of pagan European religion derived from Amonian sun worship.

John Richardson, with Sir William Jones., was Bryant's chief opponent, in the preface to his Persian Dictionary. In an anonymous pamphlet, An Apology, Bryant sustained his opinions. Richardson then revised the dissertation on languages prefixed to the dictionary, and added a second part: Further Remarks on the New Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1778). Bryant also wrote a pamphlet in answer to Daniel Wyttenbach of Amsterdam, about the same time.[31]

Bryant in the New System acknowledges help from William Barford.[32] His theories are widely credited as an influence on the mythological system of William Blake, who had worked in his capacity as an engraver on the illustrations to Bryant's New System.

Classical scholar

In his books on Troy Bryant endeavoured to show that the existence of Troy and the Greek expedition were purely mythological, with no basis in real history. Andrew Dalzel in 1791 translated a work of Jean Baptiste Le Chevalier as Description of the Plain of Troy.[33] It provoked Bryant's Observations upon a Treatise ... (on) the Plain of Troy (1795) and A Dissertation concerning the War of Troy (1796?). A fierce controversy resulted, with Bryant attacked by Thomas Falconer, John Morritt, William Vincent, and Gilbert Wakefield.[31]

Other works

- Bryant's first work was Observations and Enquiries relating to various parts of Ancient History, ... the Wind Euroclydon, the island Melite, the Shepherd Kings, (Cambridge, 1767). Bryant attacked the opinions of Bochart, Beza, Grotius, and Bentley.[31]

- When his account of the Apamean medal was disputed in the Gentleman's Magazine, Bryant defended himself in Apamean Medal and of the Inscription ΝΩΕ, London, 1775. Joseph Hilarius Eckhel upheld his views, but Daines Barrington and others opposed him in the Society of Antiquaries of London.[31]

- After his friend Robert Wood died in 1771, Bryant edited one of his works as An Essay on the Original Genius and Writings of Homer, with a Comparative View of the Troade (1775).

- Vindiciæ Flavianæ: a Vindication of the Testimony of Josephus concerning Jesus Christ (1777) was anonymous; the second edition, with Bryant's name, was in 1780. The sequel was A Farther Illustration of the Analysis (1778). This work had an impact on Joseph Priestley.[31]

- An Address to Dr. Priestley ... upon Philosophical Necessity (1780); Priestley printed a reply the same year.[31]

- Bryant was an believer in the authenticity of Thomas Chatterton's fabrications. Chatterton had created poems written in mock Middle English and had attributed them to Thomas Rowley, an imaginary monk of the 15th century. When Thomas Tyrwhitt issued his work The Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others,' Bryant with Robert Glynn followed with his Observations on the Poems of Thomas Rowley in which the Authenticity of those Poems is ascertained (2 vols., 1781).[31]

- Gemmarum Antiquarum Delectus (1783) was privately printed at the expense of the Duke of Marlborough, with engravings by Francesco Bartolozzi. The first volume was written in Latin by Bryant, and translated into French by Matthew Maty; the second by William Cole, with the French by Louis Dutens.[31]

- On the Zingara or Gypsey Language (1785) was read by Bryant to the Royal Society, and printed in the seventh volume of Archæologia.[31]

- A disquisition On the Land of Goshen, written about 1767, was published in William Bowyer's Miscellaneous Tracts, 1785.[31]

- A Treatise on the Authenticity of the Scriptures (1791) was anonymous; second edition, with author's name, 1793; third edition, 1810. This work was written at the instigation of the Dowager Countess Pembroke, daughter of his patron, and the profits were given to the hospital for smallpox and inoculation.[31]

- Observations on a controverted passage in Justyn Martyr; also upon the "Worship of Angels", London, 1793.[31]

- Observations upon the Plagues inflicted upon the Egyptians, with maps, London, 1794.[31]

- The Sentiments of Philo-Judæus concerning the Logos or Word of God (1797).

- A treatise against Tom Paine.[31]

- 'Observations upon some Passages in Scripture' (relating to Balaam, Joshua, Samson, and Jonah), London, 1803.[31]

A projected work on the Gods of Greece and Rome was not produced by his executors. Some of his humorous verse in Latin and Greek was published.[31]

References

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bryant, Jacob. |

| George Stanley Faber | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1773년 10월 25일 |

| Died | 1854년 1월 27일(80세) |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza Sophie |

| Theological work | |

| Language | English |

George Stanley Faber (often written G. S. Faber; 25 October 1773 – 27 January 1854) was an Anglican theologian and prolific author.

He was a typologist, who believed that all the world's myths were corrupted versions of the original stories in the Bible, and an advocate of Day-Age Theory. He was a contemporary of John Nelson Darby. Faber's writings had an influence on Historicism[34] and Dispensationalism.

Life

Faber, eldest son of the Rev. Thomas Faber, vicar of Calverley, Yorkshire, by Anne, daughter of the Rev. David Traviss, was born at Calverley parsonage on 25 October 1773, and educated at Hipperholme Grammar School, near Halifax, where he remained until he went to Oxford. On 10 June 1789 he matriculated from University College, being then only in his sixteenth year; he was elected a scholar on 25 March following, and took his B.A. degree when in his twentieth year. On 3 July 1793 he was elected a fellow and tutor of Lincoln College. He proceeded M.A. 1796 and B.D. 1803, served the office of proctor in 1801, and in the same year as Bampton lecturer preached a discourse, which he published under the title of Horæ Mosaicæ.

By his marriage, 31 May 1803, with Eliza Sophia, younger daughter of Major John Scott-Waring of Ince, Cheshire, he vacated his fellowship, and for the next two years acted as his father's curate at Calverley. In 1805 he was collated by Bishop Barrington to the vicarage of Stockton-on-Tees, which he resigned three years afterwards for the rectory of Redmarshall, also in Durham, and in 1811 he was presented by the same prelate to the rectory of Longnewton, in the same county, where he remained twenty-one years. Bishop Burgess collated him to a prebendal stall in Salisbury Cathedral in 1830, and Bishop van Mildert gave him the mastership of Sherburn Hospital in 1832, when he resigned the rectory of Longnewton. At Sherburn he devoted a very considerable part of his income to the permanent improvement of the hospital estates, and at his death left the buildings and the farms in perfect condition.

Views and work

Throughout his career he strenuously advocated the evangelical doctrines of the necessity of conversion, justification by faith, and the sole authority of scripture as the rule of faith. By this conduct, as well as by his able writings, he obtained the friendship of Bishop Burgess, Bishop van Mildert, Bishop Barrington, the Marquis of Bath, Lord Bexley, and Dr. Routh.

His work on The Origin of Pagan Idolatry, 1816, is prescientific in its character. He considers that all the pagan nations worshipped the same gods, who were only deified men. This began at the Tower of Babel, and the triads of supreme gods among the heathens represent the three sons of Noah. He also wrote on the Arkite Egg’ and some of his views on this subject may likewise be found in his Bampton Lectures. His treatises on the Revelations and on the Seven Vials belong to the older school of prophetic interpretation, and the restoration of the French empire under Napoleon III was brought into his scheme.

His books on the primitive doctrines of election and justification retain some importance. He laid stress on the evangelical view of these doctrines in opposition to the opinion of contemporary writers of very different schools, such as Vicesimus Knox and Joseph Milner. His works show some research and careful writing, but are not of much permanent value. He died at Sherburn Hospital, near Durham, 27 January 1854, and was buried in the chapel of the hospital on 1 February His wife died at Sherburn House 28 November 1851, aged 75.

Works

His works include:

- ‘Two Sermons before the University of Oxford, an attempt to explain by recent events five of the Seven Vials mentioned in the Revelations,’ 1799.

- ‘Horæ Mosaicæ, or a View of the Mosaical Records with respect to their coincidence with Profane Antiquity and their connection with Christianity,’ ‘Bampton Lectures,’ 1801.

- ‘A Dissertation on the Mysteries of the Cabiri, or the Great Gods of Phœnicia, Samothrace, Egypt, Troas, Greece, Italy, and Crete,’ 2 vols. 1803.

- ‘Thoughts on the Calvinistic and Arminian Controversy,’ 1803.

- ‘A Dissertation on the Prophecies relative to the Great Period of 1,200 Years, the Papal and Mahomedan Apostasies, the Reign of Antichrist, and the Restoration of the Jews,’ 2 vols. 1807; 5th ed., 3 vols. 1814–18.

- ‘A General and Connected View of the Prophecies relative to the Conversion of Judah and Israel, the Overthrow of the Confederacy in Palestine, and the Diffusion of Christianity,’ 2 vols. 1808.

- ‘A Practical Treatise on the Ordinary Operations of the Holy Spirit,’ 1813; 3rd ed. 1823.

- ‘Remarks on the Fifth Apocalyptic Vial and the Restoration of the Imperial Government of France,’ 1815.

- ‘The Origin of Pagan Idolatry ascertained from Historical Testimony and Circumstantial Evidence,’ 3 vols. 1816.

- ‘A Treatise on the Genius and Object of the Patriarchal, the Levitical, and the Christian Dispensations,’ 2 vols. 1823.

- ‘The Difficulties of Infidelity,’ 1824.

- ‘The Difficulties of Romanism,’ 1826; 3rd ed. 1853.

- ‘A Treatise on the Origin of Expiatory Sacrifice,’ 1827.

- ‘The Testimony of Antiquity against the Peculiarities of the Latin Church,’ 1828.

- ‘The Sacred Calendar of Prophecy, or a Dissertation on the Prophecies of the Grand Period of Seven Times, and of its Second Moiety, or the latter three times and a half,’ 3 vols. 1828; 2nd ed. 1844.

- ‘Letters on Catholic Emancipation,’ 1829.

- ‘The Fruits of Infidelity contrasted with the Fruits of Christianity,’ 1831.

- ‘The Apostolicity of Trinitarianism, the Testimony of History to the Antiquity and to the Apostolical Inculcation of the Doctrine of the Holy Trinity,’ 2 vols. 1832.

- ‘The Primitive Doctrine of Election, or an Enquiry into Scriptural Election as received in the Primitive Church of Christ,’ 1836; 2nd ed. 1842.

- ‘The Primitive Doctrine of Justification investigated, relatively to the Definitions of the Church of Rome and the Church of England,’ 1837.

- ‘An Enquiry into the History and Theology of the Vallenses and Albigenses, as exhibiting the Perpetuity of the Sincere Church of Christ,’ 1838.

- ‘Christ's Discourse at Capernaum fatal to the Doctrine of Transubstantiation on the very Principle of Exposition adopted by the Divines of the Roman Church,’ 1840.

- ‘Eight Dissertations on Prophetical Passages of Holy Scripture bearing upon the promise of a Mighty Deliverer,’ 2 vols. 1845.

- ‘Letters on Tractarian Secessions to Popery,’ 1846.

- ‘Papal Infallibility, a Letter to a Dignitary of the Church of Rome,’ 1851.

- ‘The Predicted Downfall of the Turkish Power, the Preparation for the Return of the Ten Tribes,’ 1853.

- ‘The Revival of the French Emperorship, anticipated from the Necessity of Prophecy,’ 1852; 5th ed. 1859.

- 'An Inquiry into the History and Theology of the Ancient Vallenses and Albigenses,' originally 1838, reprinted 1990, Church History Research & Archives

Many of these works were answered in print, and among those who wrote against Faber's views were Thomas Arnold, Shute Barrington (bishop of Durham), Christopher Bethell (bishop of Gloucester), George Corless, James Hatley Frere, Richard Hastings Graves, Thomas Harding (vicar of Bexley), Frederic Charles Husenbeth, Samuel Lee, D.D., Samuel Roffey Maitland, D.D., N. Nisbett, Thomas Pinder Pantin, Le Pappe de Trévern, and Edward William Whitaker.

Neologiser

He also coined the following words:

![]() 이 글은 퍼블릭 도메인: 〈Faber, George Stanley〉. 《영국인명사전》. 런던: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. 에서 나온 글과 연관되어 있습니다.

이 글은 퍼블릭 도메인: 〈Faber, George Stanley〉. 《영국인명사전》. 런던: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. 에서 나온 글과 연관되어 있습니다.

External links

- Works available on-line:

- The Origin of Pagan Idolatry, Vol 1. (2MB PDF.)

- Napoleon III. The Man of Prophecy (Scanned pages, 1859 American edition.)

- The Apostolicity of Trinitarianism

Algernon Herbert (12 July 1792 – 11 June 1855) was an English antiquary.[35]

Biography

Herbert was the sixth and youngest son of Henry Herbert, 1st Earl of Carnarvon by Elizabeth Alicia Maria, elder daughter of Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont. He was educated at Eton from 1805 onwards, and progressed to Christ Church, Oxford, where he matriculated on 23 October 1810. He went on to study at Exeter College, and graduated B.A. in 1813 and M.A. in 1825. He was elected a fellow of Merton College in 1814; became sub-warden in 1826, and dean in 1828.[35]

On 27 November 1818 he was called to the bar at the Inner Temple. Herbert was the author of some remarkable works replete with abstruse learning. They are, however, discursive, and his arguments are inconclusive.[35]

He married, on 2 August 1830, Marianne, sixth daughter of Thomas Lempriere of La Motte, Jersey; she died on 7 August 1870. They had one son, Sir Robert George Wyndham Herbert, and two daughters. Herbert died at Ickleton, Cambridgeshire.[35]

Works

His works were:[35]

- Nimrod, a Discourse upon Certain Passages of History and Fable, 1826; reprinted and remodelled in 2 vols., 1828, with a third volume in the same year, and vol. iv in 1829–30.

- An article on Werewolves, by A. Herbert, pp. 1–45, in The Ancient English Romance of William and the Werwolf (ed. F. Madden, Roxburghe Club, 1832).

- Britannia after the Romans, 1836–41, 2 vols.

- Nennius, the Irish version of the Historia Britonum. Introduction and Notes by A. Herbert, 1848.

- Cyclops Christianus, or the supposed Antiquity of Stonehenge, 1849.

- On the Poems of the Poor of Lyons, and three other articles in the Appendix to J. H. Todd's Books of the Vaudois (1865), pp. 93, 126, 135, 172.

Mr. Bryant의 etymology 사용과 G. S. Faber의 추구의 미진한 점: 상징의 분석과 해석에 치우치고 인간의 동기와 행동에 대해서는 덜 조사함[편집]

But it has appeared to me, in reflecting upon these subjects from time to time, that the writers who have handled them, have left their task incomplete, and in some instances taken up erroneous judgments, by confining their research too much to the analysis and interpretation of symbols, being (if I may so say) the causa materialis (즉, cause material) of Paganism, while they have but imperfectly examined and discovered the efficient and the final causes of the same, that is to say, the human motives and actions, by which the most ancient transactions (처리) on record were brought about.

이전 저술가들이 놓은 토대에 대한 저자의 입장과 태도[편집]

In giving to the public these observations of my own, I build upon the foundations which others have laid, as far as I believe in their soundness; but, knowing well the paralysing effects of a mass of ready prepared materials upon an indolent (게으른, 나태한) temper of mind, once indulged, and the inaccurate mode in which even respectable authours make their references and quotations, I have in most instances withheld myself [Page 3] the use of former compilations (편집본, 모음집), and offer little or nothing but what I have been at the pains of fetching with my own hands from the fountain head.

대홍수 이전에 일어난 일에 대한 자료는 적다[편집]

[S. II.] What passed before the flood is so little known from historical sources, and so much (그만큼의) the smaller portion of the mythological narrations relate to (~에 대해 언급하다) it (= What passed before the flood), that whatever is to be said concerning it, will better come in by way of inference from other things of more recent date, and in subsequent parts of my Essay.

대홍수 후의 배교자, 특히 님로드가 전설과 우화의 자료의 대부분을 제공한 것으로 보인다[편집]

The apostates (변절자; 배교자) after the deluge, and Nimrod especially, appear to have furnished the materials of most of the legends and fables, which exist among the various nations. Of this man, and of certain other persons, there are nearly as many names and titles, as there are mythi (신화, mythus의 복수형) or ancient romances in existence.

The Genesis flood narrative is a flood myth in the Hebrew Bible, comprising chapters 6-9 in the Book of Genesis. The narrative indicates that the God of Israel intended to return the Earth to its pre-Creation state of watery chaos by flooding the Earth for 370 days (the 150 days of flooding + the 220 days it took to dry up the floodwaters) because of the world's evil doings and then remake it using the microcosm of Noah's ark. Thus, the flood was no ordinary overflow but a reversal of creation.[36] The narrative discusses the evil of mankind that moved God to destroy the world by the way of the flood, the preparation of the ark for certain animals, Noah, and his family, and God's guarantee for the continued existence of life under the promise that he would never send another flood.[37]

Origins

Composition

According to most exegetes, the Genesis narrative is composed of two different stories (the Jahwist (YHWH) source and the Priestly (Elohim) source) that were interwoven into the final canonical form of Genesis 6-9.[38] Although there are differences in characteristic style and vocabulary, overall they are not contradictory. [36] However, where apparent contradictions do exist, they were not typically viewed as mistakes by Jewish scholars, but as allusions to deeper meanings. Even later interpreters sought to discover the basic harmony that underlies the narrative whether written by different authors, at different times, or within different cultures.[39]

Notable difficulties are:

- the two different reasons for bringing a destructive flood,

- Noah being given different instructions about what animals and birds to take on board the ark,

- the two different time frames for how long the flood lasts,

- the source of the flood waters,

- the circumstances by which Noah and the animals leave the ark, and

- the use of two different names in reference to God.[38]

Setting

The Masoretic text of the Torah, or Pentateuch, places the Great Deluge 1,656 years after Creation, or 1656 AM (Anno Mundi, "Year of the World"). Many attempts have been made to place this time-span to a specific date in history.[40] At the turn of the 17th century, Joseph Scaliger placed Creation at 3950 BC, Petavius calculated 3982 BC,[41][42] and according to James Ussher's Ussher chronology, Creation begun in 4004 BC, dating the Great Deluge to 2348 BC.[43]

- Flood Geology

The development of scientific geology had a profound impact on attitudes towards the biblical Flood narrative. Without the support of the Biblical chronology, which placed the Creation and the Flood in a history which stretched back no more than a few thousand years, the historicity of the ark itself was undermined. In 1823, William Buckland interpreted geological phenomena as Reliquiae Diluvianae: relics of the flood which "attested the action of a universal deluge". His views were supported by other English clergymen and naturalists at the time, including the influential Adam Sedgwick, but by 1830 Sedgwick considered that the evidence only showed local floods. The deposits were subsequently explained by Louis Agassiz as the results of glaciation.[44]

In 1862, William Thompson, later Lord Kelvin, calculated the age of the Earth at between 24 million and 400 million years, and for the remainder of the 19th century, discussion focused not on whether this theory of deep time was viable, but on the derivation of a more precise figure for the age of the Earth.[45] Lux Mundi, an 1889 volume of theological essays which is usually held to mark a stage in the acceptance of a more critical approach to scripture, took the stance that the gospels could be relied upon as completely historical, but that the earlier chapters of Genesis should not be taken literally.[46]

Flood narrative

Nephilim

Genesis 6:1–4 presents the Sons of God marrying the daughters of men and siring a race of giants, the "mighty men that were of old, the men of renown." Genesis continues, "And the LORD saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually."[47] God decided to destroy what he had made and start again with the righteous Noah. God chose the flood as the instrument for destruction which is portrayed as a veritable reversal of creation.[48]

Preparing the ark

Beginning with Genesis 6:14, God gives instructions to Noah to build a waterproof vessel that would house his immediate family, along with a sample of animal life.[49] The vessel is an ark made of gopher wood covered in pitch inside and outside. The ark was to be 300 cubits long, 50 cubits wide, and 30 cubits high, and have an opening for daylight near the top, an entrance on its side, and three decks. God told Noah that he, his sons, his wife, his sons’ wives, and two of each kind of beast — male and female — would survive in the Ark (Genesis 6:1-22). Seven days before the Flood, God told Noah to enter the Ark with his household, and to take seven pairs of every clean animal and every bird, and one pair of every other animal, to keep their kind alive (Genesis 7:1–5).

Great deluge

The priestly (Elohim) source of Genesis 7:11;8:1-2 describes the nature of the flood waters as a cosmic cataclysm, by the opening of the springs of the deep and the floodgates, or windows, of heaven. This is the reverse of the separation of the waters recounted in the Genesis creation narrative of chapter 1. After Noah and the remnant of animals were secured, the fountains of the great deep and the floodgates, or windows, of the heavens were opened, causing rain to fall on the Earth for 960 hours, or 40 days. The waters elevated, with the summits of the highest mountains under 15 cubits (22 feet 6 inches) of water, [49] flooding the world for 150 days, and then receding in 220 days.[50]

The Jahwist (YHWH) version of how the flood waters came to be, is indicated in Genesis 7:12 where it develops by way of a torrential downpour that lasts 40 days, then recedes in seven day periods.[50] During this time, the Ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat where Noah opens the window and sends out a raven that went to and fro. Then he sends out a dove to see if the waters had decreased from the ground, but the dove could not find a resting place, and returned to the Ark. He waited another seven days, and again sent out the dove, and the dove came back toward evening with an olive leaf. He waited another seven days and sent out the dove, and it did not return. When Noah removed the covering of the Ark, he saw that the ground was drying. (Genesis 8:1-13)

Rainbow covenant

God makes a pledge of commitment to Noah in Genesis 9:1–17. The priestly (Elohim) version takes the form of a covenant arrangement. This is the first explicit act of a covenant in the Hebrew Bible and is used seven times in this episode. God commits to continue both human and animal life and vows to never again use a second deluge against humanity. The covenant is sealed with the sign of a rainbow, after a storm, as a reminder.[51]

God blesses Noah and his sons using the same language as the priestly source of the Genesis creation narrative, "Be fruitful and increase and fill the earth."[52] Before the flood, animals and humans coexisted in a realm of peace only knowing a vegetarian diet. After the flood, God maintained that mankind would be in charge over the animals, granting that they may be eaten for food under the condition that their blood be removed.[53] God set these purity rules well before any transaction with Ancient Israel, effectively not confining such precedence solely to the Jewish faith.[54] Human life receives special divine sanction because humanity is in the image of Elohim.[55]

Islam

The Qu'ran states that Noah (Nūḥ) was inspired by the God in Islam, believed in the oneness of God, and preached Islam.[56] God commands Noah to build a ship. As he was building it, the chieftains passed him and mocked him. Upon its completion, the ship was loaded with only the animals in Noah's care[출처 필요] as well as his immediate household,[57] along with 76 who did submit to God. The people who denied the message of Noah, including one of his own sons, drowned.[58] The final resting place of the ship was referred to as Mount Judi.[59]

Yazidi

According to the Yazidi Mishefa Reş, two flood events occur. The first Deluge involved Noah and his family whose ark landed at a place called Ain Sifni in the region of Nineveh Plains, 40 킬로미터 (25 mi) north-east of Mosul. In the second flood, the Yazidi race was preserved in the person of Na'mi (or Na'umi), surnamed Malik Miran, who became the second founder of their race.[60] His ship was pierced by a rock as it floated above Mount Sinjar, but settled in the same location as it is in Islamic tradition, Mount Judi.[출처 필요]

See also

Bibliography

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2009). 《Reading the Old Testament : an introduction to the Hebrew Bible》 4판. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning. 59–66쪽. ISBN 0495391050.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2004). 《Treasures old and new : essays in the theology of the Pentateuch》. Grand Rapids, Mich. [u.a.]: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. 45쪽. ISBN 0802826792.

- Cotter, David W. (2003). 《Genesis》. Collegeville (Minn.): Liturgical press. 49–64쪽. ISBN 0814650406.

Further reading

- Hamilton, Victor P (1990). 《The book of Genesis: chapters 1-17》. Eerdmans.

- Kessler, Martin; Deurloo, Karel Adriaan (2004). 《A commentary on Genesis: the book of beginnings》. Paulist Press.

- McKeown, James (2008). 《Genesis》. Eerdmans.

- Rogerson, John William (1991). 《Genesis 1-11》. T&T Clark.

- Sacks, Robert D (1990). 《A Commentary on the Book of Genesis》. Edwin Mellen.

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). 《Genesis》. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Wenham, Gordon (2003). 〈Genesis〉. James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson. 《Eerdmans Bible Commentary》. Eerdmans.

- Whybray, R.N (2001). 〈Genesis〉. John Barton. 《Oxford Bible Commentary》. Oxford University Press.

Nimrod (/ˈnɪm.rɒd/,[61] 히브리어: נִמְרוֹדֿ, 현대 히브리어: Nimrod, 티베리아 히브리어: Nimrōḏ ܢܡܪܘܕ نمرود), king of Shinar, was, according to the Book of Genesis and Books of Chronicles, the son of Cush and great-grandson of Noah. He is depicted in the Tanakh as a man of power in the earth, and a mighty hunter. Extra-biblical traditions associating him with the Tower of Babel led to his reputation as a king who was rebellious against God. Several Mesopotamian ruins were given Nimrod's name by 8th-century Arabs[62] (see Nimrud).

Biblical account

The first mention of Nimrod is in the Table of Nations.[62] He is described as the son of Cush, grandson of Ham, and great-grandson of Noah; and as "a mighty one on the earth" and "a mighty hunter before God". This is repeated in the First Book of Chronicles 1:10, and the "Land of Nimrod" used as a synonym for Assyria or Mesopotamia, is mentioned in the Book of Micah 5:6:

- And they shall waste the land of Assyria with the sword, and the land of Nimrod in the entrances thereof: thus shall he deliver us from the Assyrian, when he cometh into our land, and when he treadeth within our borders.

Genesis says that the "beginning of his kingdom" (reshit memelketo) was the towns of "Babel, Uruk, Akkad and Calneh in the land of Shinar" (Mesopotamia) — understood variously to imply that he either founded these cities, ruled over them, or both. Owing to an ambiguity in the original Hebrew text, it is unclear whether it is he or Asshur who additionally built Nineveh, Resen, Rehoboth-Ir and Calah (both interpretations are reflected in various English versions). (Genesis 10:8–12) (Genesis 10:8-12; 1 Chronicles 1:10, Micah 5:6). Sir Walter Raleigh devoted several pages in his History of the World (c. 1616) to reciting past scholarship regarding the question of whether it had been Nimrod or Ashur who built the cities in Assyria.[63]

Traditions and legends

In Hebrew and Christian tradition, Nimrod is traditionally considered the leader of those who built the Tower of Babel in the land of Shinar,[64] though the Bible never actually states this. Nimrod's kingdom included the cities of Babel, Erech, Accad, and Calneh, all in Shinar. (Ge 10:10) Therefore it was likely under his direction that the building of Babel and its tower began; in addition to Flavius Josephus, this is also the view found in the Talmud (Chullin 89a, Pesahim 94b, Erubin 53a, Avodah Zarah 53b), and later midrash such as Genesis Rabba. Several of these early Judaic sources also assert that the king Amraphel, who wars with Abraham later in Genesis, is none other than Nimrod himself.

Judaic interpreters as early as Philo and Yochanan ben Zakai (1st century AD) interpreted "a mighty hunter before the Lord" (Heb. : לפני יהוה, lit. "in the face of the Lord") as signifying "in opposition to the Lord"; a similar interpretation is found in Pseudo-Philo, as well as later in Symmachus. Some rabbinic commentators have also connected the name Nimrod with a Hebrew word meaning 'rebel'. In Pseudo-Philo (dated ca. AD 70), Nimrod is made leader of the Hamites; while Joktan as leader of the Semites, and Fenech as leader of the Japhethites, are also associated with the building of the Tower.[65] Versions of this story are again picked up in later works such as Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius (7th century AD).

The Book of Jubilees mentions the name of "Nebrod" (the Greek form of Nimrod) only as being the father of Azurad, the wife of Eber and mother of Peleg (8:7). This account would thus make him an ancestor of Abraham, and hence of all Hebrews.

Josephus wrote:

"Now it was Nimrod who excited them to such an affront (모욕) and contempt of God. He was the grandson of Ham, the son of Noah, a bold man, and of great strength of hand. He persuaded them not to ascribe it to God, as if it were through his means they were happy, but to believe that it was their own courage which procured that happiness. He also gradually changed the government into tyranny, seeing no other way of turning men from the fear of God, but to bring them into a constant dependence on his power. He also said he would be revenged on (…에게 복수하다) God, if he should have a mind to drown the world again; for that he would build a tower too high for the waters to reach. And that he would avenge himself on God for destroying their forefathers.

avenge / revenge

avenge는 동사이고, revenge는 (대개) 명사로 쓰인다.

- avenge는 ‘avenge something(~에 대해 복수하다)’이나 ‘avenge oneself on somebody(~에게 복수하다)’ 의 형태로 쓰인다:

- She vowed to avenge her brother’s death. (그녀는 오빠[동생]의 죽음에 대해 복수를 하리라 맹세했다.)

- He later avenged himself on his wife’s killers. (그는 나중에 아내를 죽인 자들에게 복수를 했다.)

- revenge는 ‘take revenge on a person(~에게 복수하다)’의 형태로 쓰인다.

더 격식체이거나 문예체인 영어에서는 revenge도 동사로 쓰일 수 있다. 이 때는 ‘revenge oneself on somebody (~에게 복수하다)’나 ‘are revenged on somebody (~에게 복수하다)’의 형태로 쓰인다:

- He was later revenged on his wife’s killers. (그는 나중에 아내를 죽인 자들에게 복수를 했다.)

- ‘revenge something’의 형태로는 쓸 수 없다: She vowed to revenge her brother’s death. (×)

출처:Oxford Advanced Learner's English-Korean Dictionary

Now the multitude were very ready to follow the determination of Nimrod, and to esteem (생각하다) it a piece of cowardice to submit to God; and they built a tower, neither sparing any pains (수고를 아끼지 않다), nor being in any degree negligent (태만한) about the work: and, by reason of the multitude of hands employed in it, it grew very high, sooner than any one could expect; but the thickness of it was so great, and it was so strongly built, that thereby its great height seemed, upon the view, to be less than it really was. It was built of burnt brick, cemented together with mortar, made of bitumen (역청), that it might not be liable to admit water. When God saw that they acted so madly, he did not resolve to destroy them utterly, since they were not grown wiser by the destruction of the former sinners; but he caused a tumult (소란) among them, by producing in them diverse languages, and causing that, through the multitude of those languages, they should not be able to understand one another. The place wherein they built the tower is now called Babylon, because of the confusion of that language which they readily understood before; for the Hebrews mean by the word Babel, confusion…"

An early Arabic work known as Kitab al-Magall or the Book of Rolls (part of Clementine literature) states that Nimrod built the towns of Hadâniûn, Ellasar, Seleucia, Ctesiphon, Rûhîn, Atrapatene, Telalôn, and others, that he began his reign as king over earth when Reu was 163, and that he reigned for 69 years, building Nisibis, Raha (Edessa) and Harran when Peleg was 50. It further adds that Nimrod "saw in the sky a piece of black cloth and a crown." He called upon Sasan the weaver and commanded him to make him a crown like it, which he set jewels on and wore. He was allegedly the first king to wear a crown. "For this reason people who knew nothing about it, said that a crown came down to him from heaven." Later, the book describes how Nimrod established fire worship and idolatry, then received instruction in divination for three years from Bouniter, the fourth son of Noah.[66]

In the Recognitions (R 4.29), one version of the Clementines, Nimrod is equated with the legendary Assyrian king Ninus, who first appears in the Greek historian Ctesias as the founder of Nineveh. However, in another version, the Homilies (H 9.4-6), Nimrod is made to be the same as Zoroaster.

The Syriac Cave of Treasures (ca. 350) contains an account of Nimrod very similar to that in the Kitab al-Magall, except that Nisibis, Edessa and Harran are said to be built by Nimrod when Reu was 50, and that he began his reign as the first king when Reu was 130. In this version, the weaver is called Sisan, and the fourth son of Noah is called Yonton.

Jerome, writing ca. 390, explains in Hebrew Questions on Genesis that after Nimrod reigned in Babel, "he also reigned in Arach [Erech], that is, in Edissa; and in Achad [Accad], which is now called Nisibis; and in Chalanne [Calneh], which was later called Seleucia after King Seleucus when its name had been changed, and which is now in actual fact called Ctesiphon." However, this traditional identification of the cities built by Nimrod in Genesis is no longer accepted by modern scholars, who consider them to be located in Sumer, not Syria.

The Ge'ez Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan (ca. 5th century) also contains a version similar to that in the Cave of Treasures', but the crown maker is called Santal, and the name of Noah's fourth son who instructs Nimrod is Barvin.

However, Ephrem the Syrian (306-373) relates a contradictory view, that Nimrod was righteous and opposed the builders of the Tower. Similarly, Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (date uncertain) mentions a Jewish tradition that Nimrod left Shinar and fled to Assyria, because he refused to take part in building the Tower — for which God rewarded him with the four cities in Assyria, to substitute for the ones in Babel.

Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer (c. 833) relates the Jewish traditions that Nimrod inherited the garments of Adam and Eve from his father Cush, and that these made him invincible. Nimrod's party then defeated the Japhethites to assume universal rulership. Later, Esau (grandson of Abraham), ambushed (매복했다가 습격하다), beheaded, and robbed Nimrod. These stories later reappear in other sources including the 16th century Sefer haYashar, which adds that Nimrod had a son named Mardon who was even more wicked.[67]

In the History of the Prophets and Kings by the 9th century Muslim historian al-Tabari, Nimrod has the tower built in Babil, Allah destroys it, and the language of mankind, formerly Syriac, is then confused into 72 languages. Another Muslim historian of the 13th century, Abu al-Fida, relates the same story, adding that the patriarch Eber (an ancestor of Abraham) was allowed to keep the original tongue, Hebrew in this case, because he would not partake in the building. The 10th-century Muslim historian Masudi recounts a legend making the Nimrod who built the tower to be the son of Mash, the son of Aram, son of Shem, adding that he reigned 500 years over the Nabateans. Later, Masudi lists Nimrod as the first king of Babylon, and states that he dug great canals and reigned 60 years. Still elsewhere, he mentions another king Nimrod, son of Canaan, as the one who introduced astrology and attempted to kill Abraham.

In Armenian legend, the ancestor of the Armenian people, Hayk, defeated Nimrod (sometimes equated with Bel) in a battle near Lake Van.

In the Hungarian legend of the Enchanted Stag (마법에 걸린 수사슴) (more commonly known as the White Stag [Fehér Szarvas] or Silver Stag), King Nimród (aka Ménrót and often described as "Nimród the Giant" or "the giant Nimród", descendant of one of Noah's "most wicked" sons, Kam - references abound in traditions, legends, several religions and historical sources to persons and nations bearing the name of Kam or Kám, and overwhelmingly, the connotations are negative), is the first person referred to as forefather of the Hungarians. He, along with his entire nation, is also the giant responsible for the building of the Tower of Babel - construction of which was supposedly started by him 201 years after the event of the Great Flood (see biblical story of Noah's Ark &c.). After the catastrophic failure (through God's will) of that most ambitious endeavour and in the midst of the ensuing linguistic cacophony (불협화음), Nimród the giant moved to the land of Evilát, where his wife, Enéh gave birth to twin brothers Hunor and Magyar (aka Magor). Father and sons were, all three of them, prodigious (엄청난) hunters, but Nimród especially is the archetypal, consummate (완벽한), legendary hunter and archer. Both the Huns' and Magyars' historically attested skill with the recurve (뒤로 휘다) bow and arrow are attributed to Nimród. (Simon Kézai, personal "court priest" of King László Kún, in his Gesta Hungarorum, 1282-85. This tradition can also be found in over twenty other medieval Hungarian chronicles, as well as a German one, according to Dr Antal Endrey in an article published in 1979).

The twin sons of King Nimród, Hunor and Magor, each with 100 warriors, followed the White Stag through the Meotis Marsh, where they lost sight of the magnificent animal. Hunor and Magor found the two daughters of King Dul of the Alans, together with their handmaidens (하녀), whom they kidnapped. Hungarian legends held Hunor and Magyar (aka Magor) to be ancestors of the Huns and the Magyars (Hungarians), respectively.

According to the Miholjanec legend, Stephen V of Hungary had in front of his tent a golden plate with the inscription: "Attila, the son of Bendeuci, grandson of the great Nimrod, born at Engedi: By the Grace of God King of the Huns, Medes, Goths, Dacians, the horrors of the world and the scourge (재앙, 골칫거리) of God."

The evil Nimrod vs. the righteous Abraham

The Bible does not mention any meeting between Nimrod and Abraham, although a confrontation between the two is said to have taken place, according to several Jewish and Islamic traditions. Some stories bring them both together in a cataclysmic (대격변) collision, seen as a symbol of the confrontation between Good and Evil, and/or as a symbol of monotheism against polytheism. On the other hand, some Jewish traditions say only that the two men met and had a discussion.[9]

According to K. van der Toorn; P. W. van der Horst, this tradition is first attested in the writings of Pseudo-Philo.[68] The story is also found in the Talmud, and in rabbinical writings in the Middle Ages.[69]

In some versions (as in Flavius Josephus), Nimrod is a man who sets his will against that of God. In others, he proclaims himself a god and is worshipped as such by his subjects, sometimes with his consort Semiramis worshipped as a goddess at his side. (See also Ninus.)

A portent (징조) in the stars tells Nimrod and his astrologers of the impending birth of Abraham, who would put an end to idolatry. Nimrod therefore orders the killing of all newborn babies. However, Abraham's mother escapes into the fields and gives birth secretly. At a young age, Abraham recognizes God and starts worshiping Him. He confronts Nimrod and tells him face-to-face to cease his idolatry, whereupon Nimrod orders him burned at the stake. In some versions, Nimrod has his subjects gather wood for four whole years, so as to burn Abraham in the biggest bonfire (모닥불) the world had ever seen. Yet when the fire is lit, Abraham walks out unscathed (하나도 다치지 않은).

In some versions, Nimrod then challenges Abraham to battle. When Nimrod appears at the head of enormous armies, Abraham produces an army of gnats (각다귀) which destroys Nimrod's army. Some accounts have a gnat or mosquito enter Nimrod's brain and drive him out of his mind (a divine retribution which Jewish tradition also assigned to the Roman Emperor Titus (39 - 81), destroyer of the Temple in Jerusalem).

In some versions, Nimrod repents and accepts God, offering numerous sacrifices that God rejects (as with Cain). Other versions have Nimrod give to Abraham, as a conciliatory (회유하기 위한) gift, the slave Eliezer, whom some accounts describe as Nimrod's own son. (The Bible also mentions Eliezer as Abraham's majordomo (집사), though not making any connection between him and Nimrod.)

Still other versions have Nimrod persisting in his rebellion against God, or resuming it. Indeed, Abraham's crucial act of leaving Mesopotamia and settling in Canaan is sometimes interpreted as an escape from Nimrod's revenge. Accounts considered canonical place the building of the Tower many generations before Abraham's birth (as in the Bible, also Jubilees); however in others, it is a later rebellion after Nimrod failed in his confrontation with Abraham. In still other versions, Nimrod does not give up after the Tower fails, but goes on to try storming (기습[급습]하다) Heaven in person, in a chariot driven by birds.

The story attributes to Abraham elements from the story of Moses' birth (the cruel king killing innocent babies, with the midwives (산파) ordered to kill them) and from the careers of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego who emerged unscathed from the fire. Nimrod is thus given attributes of two archetypal cruel and persecuting kings - Nebuchadnezzar and Pharaoh. Some Jewish traditions also identified him with Cyrus (c. 600 BC or 576 BC–530 BC) whose birth according to Herodotus was accompanied by portents which made his grandfather try to kill him.

A confrontation is also found in the Islamic Qur'an, between a king, not mentioned by name, and the Prophet Ibrahim (Arabic version of "Abraham"). Muslim commentators assign Nimrod as the king based on Jewish sources. In Ibrahim's confrontation with the king, the former argues that Allah (God) is the one who gives life and gives death. The king responds by bringing out two people sentenced to death. He releases one and kills the other as a poor attempt at making a point that he also brings life and death. Ibrahim refutes him by stating that Allah brings the Sun up from the East, and so he asks the king to bring it from the West. The king is then perplexed and angered.

Whether or not conceived as having ultimately repented, Nimrod remained in Jewish and Islamic tradition an emblematic (전형적인, 상징적인) evil person, an archetype of an idolater and a tyrannical king. In rabbinical writings up to the present, he is almost invariably referred to as "Nimrod the Evil" (נמרוד הרשע)"

The story of Abraham's confrontation with Nimrod did not remain within the confines of learned writings and religious treatises, but also conspicuously influenced popular culture. A notable example is "Quando el Rey Nimrod" ("When King Nimrod"), one of the most well-known folksongs in Ladino (the Judeo-Spanish language), apparently written during the reign of King Alfonso X of Castile. Beginning with the words: "When King Nimrod went out to the fields/ Looked at the heavens and at the stars/He saw a holy light in the Jewish quarter/A sign that Abraham, our father, was about to be born", the song gives a poetic account of the persecutions perpetrated (저지르다) by the cruel Nimrod and the miraculous birth and deeds of the savior Abraham.[70]

Text of the Midrash Rabba version

The following version of the Abraham vs. Nimrod confrontation appears in the Midrash Rabba, a major compilation of Jewish Scriptural exegesis. The part relating to Genesis, in which this appears (Chapter 38, 13), is considered to date from the sixth century.

|

נטלו ומסרו לנמרוד. אמר לו: עבוד לאש. אמר לו אברהם: ואעבוד למים, שמכבים את האש? אמר לו נמרוד: עבוד למים! אמר לו: אם כך, אעבוד לענן, שנושא את המים? אמר לו: עבוד לענן! אמר לו: אם כך, אעבוד לרוח, שמפזרת עננים? אמר לו: עבוד לרוח! אמר לו: ונעבוד לבן אדם, שסובל הרוחות? אמר לו: מילים אתה מכביר, אני איני משתחוה אלא לאוּר - הרי אני משליכך בתוכו, ויבא אלוה שאתה משתחוה לו ויצילך הימנו! היה שם הרן עומד. אמר: מה נפשך, אם ינצח אברהם - אומַר 'משל אברהם אני', ואם ינצח נמרוד - אומַר 'משל נמרוד אני'. כיון שירד אברהם לכבשן האש וניצול, אמרו לו: משל מי אתה? אמר להם: משל אברהם אני! נטלוהו והשליכוהו לאור, ונחמרו בני מעיו ויצא ומת על פני תרח אביו. וכך נאמר: וימת הרן על פני תרח אביו. (בראשית רבה ל"ח, יג) |

(...) He [Abraham] was given over to Nimrod. [Nimrod] told him: Worship the Fire! Abraham said to him: Shall I then worship the water, which puts off the fire! Nimrod told him: Worship the water! [Abraham] said to him: If so, shall I worship the cloud, which carries the water? [Nimrod] told him: Worship the cloud! [Abraham] said to him: If so, shall I worship the wind, which scatters the clouds? [Nimrod] said to him: Worship the wind! [Abraham] said to him: And shall we worship the human, who withstands the wind? Said [Nimrod] to him: You pile words upon words, I bow to none but the fire - in it shall I throw you, and let the God to whom you bow come and save you from it! |

Historical interpretations

Historians and mythographers have long tried to find links between Nimrod and attested historical figures. No king named Nimrod is to be found anywhere in the ancient and extensive Mesopotamian records, including the Assyrian King List, nor the king lists of the Sumerians, Akkadian Empire, Babylonia or Chaldea.

Nimrod as Euechoios · Euechoros · Enmerkar

The Christian Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea as early as the early 4th century, noting that the Chaldean historian Berossus in the 3rd century BC had stated that the first king after the flood was Euechoios of Chaldea, identified him with Nimrod. George Syncellus (c. 800) also had access to Berossus, and he too identified Euechoios with the biblical Nimrod.

More recently, Sumerologists have suggested [the same identifiation] additionally connecting both this Euechoios, and the king of Babylon and grandfather of Gilgamos who appears in the oldest copies of Aelian (c. 200 AD) as Euechoros, with the name of the founder of Uruk known from cuneiform sources as Enmerkar.[71]

Nimrod as Lord (Ni) of Marad

J.D.Prince, in 1920 also suggested a possible link between the Lord (Ni) of Marad and Nimrod.

Nimrod as Lugal-Banda

He (J.D.Prince) mentioned how Dr. Kraeling was now inclined to connect Nimrod historically with Lugal-Banda, a mythological king mentioned in Poebel, Historical Texts, 1914, whose seat was at the city Marad.[72] This is supported by Theodore Jacobson in 1989, writing on "Lugalbanda and Ninsuna".[73]

Nimrod as Ninurta

According to Ronald Hendel the name Nimrod is probably a polemical distortion of Ninurta, who had cult centers in Babel and Calah, and was a patron god of the Neo-Assyrian kings.[74]

Nimrod as Marduk

Marduk (Merodach), has been suggested as a possible archetype for Nimrod, especially at the beginning of the 20th century. [출처 필요]

Nimrod as Tukulti-Ninurta I

Nimrod's imperial ventures described in Genesis may be based on the conquests of the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (Dalley et al., 1998, p. 67). Julian Jaynes also indicates Tukulti-Ninurta I as the origin for Nimrod.[75]

Nimrod as Ninus

Alexander Hislop, in his tract The Two Babylons (Chapter 2, Section II, Sub-Section I) decided that Nimrod was to be identified with Ninus, who according to Greek legend was a Mesopotamian king and husband of Semiramis (see below);

Nimrod as a whole host of deities throughout the Mediterranean world

[Nimrod was identified] with a whole host of deities throughout the Mediterranean world,

Nimrod as Zoroaster

and [Nimrod was identified] with the Persian Zoroaster.

The identification with Ninus follows that of the Clementine Recognitions; the one with Zoroaster, that of the Clementine Homilies, both works part of Clementine literature.[76]

Nimrod as Asar · Baal · Dumuzi · Osiris · Enmerkar

David Rohl, like Hislop, identified Nimrod with a complex of Mediterranean deities; among those he picked were Asar, Baal, Dumuzi and Osiris. In Rohl's theory, Enmerkar the founder of Uruk was the original inspiration for Nimrod, because the story of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (see:[77]) bears a few similarities to the legend of Nimrod and the Tower of Babel, and because the -KAR in Enmerkar means "hunter". Additionally, Enmerkar is said to have had ziggurats built in both Uruk and Eridu, which Rohl postulates was the site of the original Babel.

Nimrod as Belus

George Rawlinson believed Nimrod was Belus based on the fact Babylonian and Assyrian inscriptions bear the names inscriptions Bel-Nimrod or Bel-Nibru.[78] The word Nibru comes from a root meaning to 'pursue' or to make 'one flee', and as Rawlinson pointed out not only does this closely resemble Nimrod’s name but it also perfectly fits the description of Nimrod in Genesis 10: 9 as a great hunter. The Belus-Nimrod equation or link is also found in many old works such as Moses of Chorene and the Book of the Bee.[79]

Nimrod as a king of the first dynasty or Uruk

Joseph Poplicha wrote in 1929 about the identification of Nimrod of [a king of Kingdom of Eanna] in the first dynasty or Uruk[80]

Nimrod as Sargon the Great

Because another of the cities said to have been built by Nimrod was Accad, an older theory, proposed by 1910,[81] connects him with Sargon the Great, grandfather of Naram-Sin, since, according to the Sumerian king list, that king first built Agade (Akkad). Sargon was known from archaeology by 1860, and for some time remained the earliest-known Mesopotamian ruler. The assertion of the king list that it was Sargon who built Akkad has since been called into question, however, with the discovery of inscriptions mentioning the place in the reigns of some of Sargon's predecessors, such as kings Enshakushanna and Lugal-Zage-Si of Uruk. Moreover, Sargon was credited with founding Babylon in the Babylonian Chronicle (ABC 19:51), another city (Babel) attributed to Nimrod in Genesis. However, a different tablet (ABC 20:18-19) suggests that Sargon merely "dug up the dirt of the pit" of the original Babylon, and rebuilt it in its later location fronting Akkad.

Nimrod as Sargon the Great · Naram-Sin

Yigal Levin (2002) suggests that Nimrod was a recollection of Sargon of Akkad and of his grandson Naram-Sin, with the name "Nimrod" derived from the latter.[82]

Nimrod as one of the founders of Masonry

Nimrod figures in some very early versions of the history of Freemasonry, where he was said to have been one of the fraternity's founders. According to the Encyclopedia of Freemasonry: The legend of the Craft in the Old Constitutions refers to Nimrod as one of the founders of Masonry. Thus in the York MS., No. 1, we read: "At ye making of ye toure of Babell there was a Masonrie first much esteemed of, and the King of Babilon yt called Nimrod was a Mason himself and loved well Masons." However, he does not figure in the current rituals.

Nimrod as Nyyrikki

The demon Nyyrikki, figuring in the Finnish Kalevala as a helper of Lemminkäinen, is associated with Nimrod by some researchers and linguists.[83]

Literature

- In the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (written 1308-21), Nimrod is a figure in the Inferno. Nimrod is portrayed as a giant (which was common in the Medieval period) and is found with the other giants Ephialtes, Antaeus, Briareus, Tityos, Typhon and the other unnamed giants chained up on the outskirts (변두리) of Hell's Circle of Treachery (배반). His only line is "Raphèl maí amèche zabí almi", an unintelligible statement which serves to accuse himself.[84]

Idiom

In 15th-century English, "Nimrod" had come to mean "tyrant". Coined in 20th-century American English, the term is now commonly used to mean "dimwitted (우둔한) or stupid fellow", a usage first recorded in 1932 and popularized by the cartoon character Bugs Bunny, who sarcastically (풍자적으로) refers to the hunter Elmer Fudd as "nimrod",[85][86] possibly as an ironic connection between "mighty hunter" and "poor little Nimrod", i.e. Fudd.[87]

See also

References

- The Legacy of Mesopotamia; Stephanie Dalley et al. (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998)

- Noah's Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery; Stephen R. Haynes (NY, Oxford University Press, 2002)

- "Nimrod before and after the Bible" K. van der Toorn; P. W. van der Horst, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 83, No. 1. (Jan., 1990), pp. 1–29

External links

- Nimrod, entry in the Jewish Encyclopedia

- WebBible entry

- Against World Powers: A Study of the Judeo-Christian Struggle in History and Prophecy - Modern Christian writings which follow David Rohl's view on the legends of Nimrod. Another page from this site summarizes Rohl's theory of Nimrod and Enmerkar

오리온은 님로드의 여러 다른 이름 가운데 하나로, 추론이 아닌 전통과 사실이 문제되는 유일한 경우이다[편집]

Orion is almost the only one of these names (즉, 님로드 혹은 이 유형의 다른 이들의 여러 이름) whereof (무엇[어떤 것]에 대해) the application to him is matter of tradition and fact, and not of inductive comparison.

오리온과 님로드에 대한 여러 원천문서의 진술들[편집]

구약성경에 따르면 오리온 즉 님로드는 son of Cush son of Ham이다[편집]

Scripture relates that he was the son of Cush son of Ham;

Paschal Chronicle의 모순된 언급[편집]

with which (즉 구약성경) the Paschal3) or Alexandrine Chronicle agrees, saying that,

- "Chus AEthiops was son of Cham, and that from him came Nembrod the Huntsman and Giant, the AEthiopian, from whom were the Mysians... He taught the Assyrians to worship fire."

3) p. 28. 29. ed. Paris. 1688.

But this work (즉, Paschal Chronicle) is in several places contradictory, and must have been interpolated long after its original composition; presently afterwards it says4),

- "Chus AEthiops of the tribe of Shem, begot Nembrod the giant, who founded Babylonia, who, as the Persians say, was deified and became that star in the heavens which they call Orion. This Nembrod first taught people how to hunt wild animals for food, and was the first great man among the Persians."

4) p. 36.

There may be reason to think that the errour here is not accidental, but arises from a wish to conciliate (달래다, 회유하다) to this great apostate the prophecy of Noah in favour [Page B2] [Page 4] of Shem.

Mysians (Mysi, Μυσοί) were the inhabitants of Mysia, a region in northwestern Asia Minor.

Origins according to ancient authors

Their first mention is by Homer, in his list of Trojans allies in the Iliad, and according to whom the Mysians fought in the Trojan War on the side of Troy, under the command of Chromis and Ennomus the Augur, and were lion-hearted spearmen who fought with their bare hands.[88]

Herodotus in his Histories wrote that the Mysians were brethren of the Carians and the Lydians, originally Lydian colonists in their country, and as such, they had the right to worship alongside their relative nations in the sanctuary dedicated to the Carian Zeus in Mylasa.[89] He also mentions a movement of Mysians and associated peoples from Asia into Europe still earlier than the Trojan War, wherein the Mysians and Teucrians had crossed the Bosphorus into Europe and, after conquering all of Thrace, pressed forward till they came to the Ionian Sea, while southward they reached as far as the river Peneus.[90] Herodotus adds an account and description of later Mysians who fought in Darius' army.

Strabo in his Geographica informs that, according to his sources, the Mysians in accordance with their religion abstained from eating any living thing, including from their flocks, and that they used as food honey and milk and cheese.[91] Citing the historian Xanthus, he also reports that the name of the people was derived from the Lydian name for the oxya tree.

Mysian language

Little is known about the Mysian language. Strabo noted that their language was, in a way, a mixture of the Lydian and Phrygian languages. As such, the Mysian language could be a language of the Anatolian group. However, a passage in Athenaeus suggests that the Mysian language was akin to the barely attested Paeonian language of Paeonia, north of Macedon.

A short inscription which could be in Mysian and which dates from between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC was found in Üyücek, near Kütahya, and seems to include Indo-European words, but it has not been deciphered.[92]

See also

Chronicon Paschale ("the Paschal Chronicle, also Chronicum Alexandrinum or Constantinopolitanum, or Fasti Siculi) is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name comes from its system of chronology based on the Christian paschal cycle; its Greek author named it "Epitome of the ages from Adam the first man to the 20th year of the reign of the most August Heraclius."

The Chronicon Paschale follows earlier chronicles. For the years 600 to 627 the author writes as a contemporary historian - that is, through the last years of emperor Maurice, the reign of Phocas, and the first seventeen years of the reign of Heraclius.

Like many chroniclers, the author of this popular account relates anecdotes, physical descriptions of the chief personages (which at times are careful portraits), extraordinary events such as earthquakes and the appearance of comets, and links Church history with a supposed Biblical chronology. Sempronius Asellio points out the difference in the public appeal and style of composition which distinguished the chroniclers (Annales) from the historians (Historia) of the Eastern Roman Empire.

The "Chronicon Paschale" is a huge compilation, attempting a chronological list of events from the creation of Adam. The principal manuscript, the 10th-century Codex Vaticanus græcus 1941, is damaged at the beginning and end and stops short at 627. The Chronicle proper is preceded by an introduction containing reflections on Christian chronology and on the calculation of the Paschal (Easter) cycle. The so-called 'Byzantine' or 'Roman' era (which continued in use in Greek Orthodox Christianity until the end of Turkish rule as the 'Julian calendar') was adopted in the Chronicum as the foundation of chronology; in accordance with which the date of the creation is given as the 21 March 5507.

The author identifies himself as a contemporary of the Emperor Heraclius (610-641), and was possibly a cleric attached to the suite of the œcumenical Patriarch Sergius. The work was probably written during the last ten years of the reign of Heraclius.

The chief authorities used were: Sextus Julius Africanus; the consular Fasti; the Chronicle and Church History of Eusebius; John Malalas; the Acta Martyrum; the treatise of Epiphanius, bishop of Constantia (the old Salamis) in Cyprus (fl. 4th century), on Weights and Measures.

Editions

- L. Dindorf (1832) in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae, with du Cange's preface and commentary

- J. P. Migne, Patrologia graeca, vol. 92.

- See also C. Wachsmuth, Einleitung in das Studien der alten Geschichte (1895)

- H. Gelzer, Sextus Julius Africanus und die byzantinische Chronographie, ii. I (1885)

- J. van der Hagen, Observationes in Heraclii imperatoris methodum paschalem (1736, but still considered indispensable)

- E. Schwarz in Pauly–Wissowa, Realencyclopädie, iii., Pt. 2 (1899)

- C. Krumbacher, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur (1897).

Partial English translation

- Chronicon Paschale 284–628 AD, translated by Michael Whitby and Mary Whitby (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1989) ISBN 0-85323-096-X

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Chronicon Paschale〉. 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Chronicon Paschale〉. 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press. 본 문서에는 현재 퍼블릭 도메인에 속한 1913년 가톨릭 백과사전의 "Chronicon Paschale" 항목을 기초로 작성된 내용이 포함되어 있습니다.

본 문서에는 현재 퍼블릭 도메인에 속한 1913년 가톨릭 백과사전의 "Chronicon Paschale" 항목을 기초로 작성된 내용이 포함되어 있습니다.

External links

- Chronicon Paschale (Catholic Encyclopedia)

- Paschal Chronicle (1911 Encyclopædia Britannica)

- Chronicon Paschale (Olympiads 112–187)

- 1832 Dindorf edition at Google Books: Vol.1; Vol. 2.

Revelations of Methodius의 진술: 님로드는 God의 영감을 받았다[편집]

There is a book to be found in some libraries, called the Revelations of Methodius, bishop of Tyre. The authour of which hath the impudence (뻔뻔스러움) to deliver the following statement.