사용자:구순돌/연습장/닥터 드레

| Dr. Dre | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dr. Dre in 2011 | |||||||||||

| 본명 | Andre Romelle Young | ||||||||||

| 출생 | 1965년 2월 18일(59세) Compton, California, U.S. | ||||||||||

| 별칭 |

| ||||||||||

| 직업 |

| ||||||||||

| 활동 기간 | 1985–present | ||||||||||

| 순자산 | US$800 million (2019) | ||||||||||

| 배우자 | Nicole Plotzker(1996;div. 2021년 결혼) | ||||||||||

| 자녀 | 8 | ||||||||||

| 친척 | Sir Jinx (cousin) Warren G (step-brother) Olaijah Griffin (step-nephew) | ||||||||||

| 상훈 | Full list | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Andre Romelle Young (born February 18, 1965), known professionally as Dr. Dre, is an American rapper, record producer, and entrepreneur. He is the founder and CEO of Aftermath Entertainment and Beats Electronics, and previously co-founded, co-owned, and was the president of Death Row Records. Dr. Dre began his career as a member of the World Class Wreckin' Cru in 1985 and later found fame with the gangsta rap group N.W.A. The group popularized explicit lyrics in hip hop to detail the violence of street life. During the early 1990s, Dre was credited as a key figure in the crafting and popularization of West Coast G-funk, a subgenre of hip hop characterized by a synthesizer foundation and slow, heavy beats.

Dre's solo debut studio album The Chronic (1992), released under Death Row Records, made him one of the best-selling American music artists of 1993. It earned him a Grammy Award for Best Rap Solo Performance for the single "Let Me Ride", as well as several accolades for the single "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang". That year, he produced Death Row labelmate Snoop Doggy Dogg's debut album Doggystyle and mentored producers such as his stepbrother Warren G (leading to the multi-platinum debut Regulate...G Funk Era in 1994) and Snoop Dogg's cousin Daz Dillinger (leading to the double-platinum debut Dogg Food by Tha Dogg Pound in 1995), as well as mentor to upcoming producers Sam Sneed and Mel-Man. In 1996, Dr. Dre left Death Row Records to establish his own label, Aftermath Entertainment. He produced a compilation album, Dr. Dre Presents the Aftermath, in 1996, and released a solo album, 2001, in 1999.

During the 2000s, Dre focused on producing other artists, occasionally contributing vocals. He signed Eminem in 1998 and 50 Cent in 2002, and co-produced their albums. He has produced albums for and overseen the careers of many other rappers, including the D.O.C., Snoop Dogg, Xzibit, Knoc-turn'al, the Game, Kendrick Lamar, and Anderson .Paak. Dre has also had acting roles in movies such as Set It Off, The Wash, and Training Day. He has won six Grammy Awards, including Producer of the Year, Non-Classical. Rolling Stone ranked him number 56 on the list of 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. He was the second-richest figure in hip hop as of 2018 with an estimated net worth of $800 million.

Accusations of Dre's violence against women have been widely publicized. Following his assault of television host Dee Barnes, he was fined $2,500, given two years' probation, ordered to perform 240 hours of community service, and given a spot on an anti-violence public service announcement. A civil suit was settled out of court. In 2015, Michel'le, the mother of one of his children, accused him of domestic violence during their time together as a couple. Their abusive relationship is portrayed in her 2016 biopic Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge & Michel'le. Lisa Johnson, the mother of three of Dr. Dre's children, stated that he beat her many times, including while she was pregnant. She was granted a restraining order against him. Former labelmate Tairrie B claimed that Dre assaulted her at a party in 1990, in response to her track "Ruthless Bitch". Two weeks following the release of his third album, Compton in August 2015, he issued an apology to the women "I've hurt".[1]

Early life[편집]

Dre was born Andre Romelle Young[2] in Compton, California, on February 18, 1965,[3] the son of Theodore and Verna Young. His middle name is derived from the Romells, his father's amateur R&B group. His parents married in 1964, separated in 1968, and divorced in 1972. His mother later remarried to Curtis Crayon and had three children: sons Jerome and Tyree (both deceased) and daughter Shameka.[4]

In 1976, Dre began attending Vanguard Junior High School in Compton, but due to gang violence, he transferred to the safer suburban Roosevelt Junior High School.[5] The family moved often and lived in apartments and houses in Compton, Carson, Long Beach, and the Watts and South Central neighborhoods of Los Angeles.[6] Dre has said that he was mostly raised by his grandmother in the New Wilmington Arms housing project in Compton.[7] His mother later married Warren Griffin,[8] which added three step-sisters and one step-brother to the family; the latter would eventually begin rapping under the name Warren G.[9] Dre is also the cousin of producer Sir Jinx. Dre attended Centennial High School in Compton during his freshman year in 1979, but transferred to Fremont High School in South Central Los Angeles due to poor grades. He attempted to enroll in an apprenticeship program at Northrop Aviation Company, but poor grades at school made him ineligible. Thereafter, he focused on his social life and entertainment for the remainder of his high school years.[10]

Dre's frequent absences from school jeopardized his position as a diver on his school's swim team. After high school, he attended Chester Adult School in Compton following his mother's demands for him to get a job or continue his education. After brief attendance at a radio broadcasting school, he relocated to the residence of his father and residence of his grandparents before returning to his mother's house.[11]

Musical career[편집]

1985–1986: World Class Wreckin' Cru[편집]

Inspired by the Grandmaster Flash song "The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel", Dr. Dre often attended a club called Eve's After Dark to watch many DJs and rappers performing live. He subsequently became a DJ in the club, initially under the name "Dr. J", based on the nickname of Julius Erving, his favorite basketball player. At the club, he met aspiring rapper Antoine Carraby, later to become member DJ Yella of N.W.A.[12] Soon afterwards he adopted the moniker Dr. Dre, a mix of previous alias Dr. J and his first name, referring to himself as the "Master of Mixology".[13]

Eve After Dark had a back room with a small four-track studio. In this studio, Dre and Yella recorded several demos. In their first recording session, they recorded a song entitled "Surgery".[14][15] Dr. Dre's earliest recordings were released in 1994 on a compilation titled Concrete Roots. Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine of allmusic described the compiled music, released "several years before Dre developed a distinctive style", as "surprisingly generic and unengaging" and "for dedicated fans only".[16]

Dre later joined the musical group World Class Wreckin' Cru, which released its debut album under the Kru-Cut label in 1985.[17] The group would become stars of the electro-hop scene that dominated early-mid 1980s West Coast hip hop. "Surgery", which was officially released after being recorded prior to the group's official formation, would prominently feature Dr. Dre on the turntable. The record would become the group's first hit, selling 50,000 copies within the Compton area.[18] Dr. Dre and DJ Yella also performed mixes for local radio station KDAY, boosting ratings for its afternoon rush-hour show The Traffic Jam.[19]

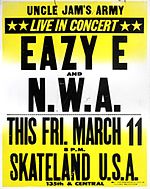

1986–1991: N.W.A and Ruthless Records[편집]

In 1986, Dr. Dre met rapper O'Shea Jackson—known as Ice Cube—who collaborated with him to record songs for Ruthless Records, a hip hop record label run by local rapper Eazy-E. N.W.A and fellow West Coast rapper Ice-T are widely credited as seminal artists of the gangsta rap genre, a profanity-heavy subgenre of hip hop, replete with gritty depictions of urban crime and gang lifestyle. Not feeling constricted to racially charged political issues pioneered by rap artists such as Public Enemy or Boogie Down Productions, N.W.A favored themes and uncompromising lyrics, offering stark descriptions of violent, inner-city streets. Propelled by the hit "Fuck tha Police", the group's first full album Straight Outta Compton became a major success, despite an almost complete absence of radio airplay or major concert tours. The Federal Bureau of Investigation sent Ruthless Records a warning letter in response to the song's content.[20]

After Ice Cube left N.W.A in 1989 over financial disputes, Dr. Dre produced and performed for much of the group's second album Efil4zaggin. He also produced tracks for a number of other acts on Ruthless Records, including Eazy-E's 1988 solo debut Eazy-Duz-It, Above the Law's 1990 debut Livin' Like Hustlers, Michel'le's 1989 self-titled debut, the D.O.C.'s 1989 debut No One Can Do It Better, J.J. Fad's 1988 debut Supersonic and funk rock musician Jimmy Z's 1991 album Muzical Madness.[21][22]

1991–1996: The Chronic and Death Row Records[편집]

After a dispute with Eazy-E, Dre left the group at the peak of its popularity in 1991 under the advice of friend, and N.W.A lyricist, the D.O.C. and his bodyguard at the time, Suge Knight. Knight, a notorious strongman and intimidator, was able to have Eazy-E release Young from his contract and, using Dr. Dre as his flagship artist, founded Death Row Records. In 1992, Young released his first single, the title track to the film Deep Cover, a collaboration with rapper Snoop Dogg, whom he met through Warren G.[20] Dr. Dre's debut solo album was The Chronic, released under Death Row Records with Suge Knight as executive producer. Young ushered in a new style of rap, both in terms of musical style and lyrical content, including introducing a number of artists to the industry including Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, Daz Dillinger, RBX, the Lady of Rage, Nate Dogg and Jewell.[23]

On the strength of singles such as "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang", "Let Me Ride", and "Fuck wit Dre Day (and Everybody's Celebratin')" (known as "Dre Day" for radio and television play), all of which featured Snoop Dogg as guest vocalist, The Chronic became a cultural phenomenon, its G-funk sound dominating much of hip hop music for the early 1990s.[20] In 1993, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) certified the album triple platinum,[24] and Dr. Dre also won the Grammy Award for Best Rap Solo Performance for his performance on "Let Me Ride".[25] For that year, Billboard magazine also ranked Dr. Dre as the eighth best-selling musical artist, The Chronic as the sixth best-selling album, and "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang" as the 11th best-selling single.[26]

Besides working on his own material, Dr. Dre produced Snoop Dogg's debut album Doggystyle, which became the first debut album for an artist to enter the Billboard 200 album charts at number one.[27] In 1994 Dr. Dre produced some songs on the soundtracks to the films Above the Rim and Murder Was the Case. He collaborated with fellow N.W.A member Ice Cube for the song "Natural Born Killaz" in 1995.[20] For the film Friday, Dre recorded "Keep Their Heads Ringin'", which reached number ten on the Billboard Hot 100 and number 1 on the Hot Rap Singles (now Hot Rap Tracks) charts.[28]

In 1995, Death Row Records signed rapper 2Pac, and began to position him as their major star: he collaborated with Dr. Dre on the commercially successful single "California Love", which became both artists' first song to top the Billboard Hot 100.[20][29] However, in March 1996 Young left the label amidst a contract dispute and growing concerns that label boss Suge Knight was corrupt, financially dishonest and out of control. Later that year, he formed his own label, Aftermath Entertainment, under the distribution label for Death Row Records, Interscope Records.[20] Subsequently, Death Row Records suffered poor sales by 1997, especially following the death of 2Pac and the racketeering charges brought against Knight.[30]

Dr. Dre also appeared on the single "No Diggity" by R&B group Blackstreet in 1996: it too was a sales success, topping the Hot 100 for four consecutive weeks, and later won the award for Best R&B Vocal by a Duo or Group at the 1997 Grammy Awards.[31] After hearing it for the first time, several of Dr. Dre's former Death Row colleagues, including 2Pac, recorded and attempted to release a song titled "Toss It Up", containing numerous insults aimed at Dr. Dre and using a deliberately similar instrumental to "No Diggity", but were forced to replace the production after Blackstreet issued the label with a cease and desist order stopping them from distributing the song.[32]

1996–2000: Move to Aftermath Entertainment and 2001[편집]

The Dr. Dre Presents the Aftermath album, released on November 26, 1996, featured songs by Dr. Dre himself, as well as by newly signed Aftermath Entertainment artists, and a solo track "Been There, Done That", intended as a symbolic farewell to gangsta rap.[33] Despite being classified platinum by the RIAA,[24] the album was not very popular among music fans.[20] In October 1996, Dre performed "Been There, Done That" on Saturday Night Live.[34] In 1997, Dr. Dre produced several tracks on the Firm's The Album; it was met with largely negative reviews from critics. Rumors began to abound that Aftermath was facing financial difficulties.[35] Aftermath Entertainment also faced a trademark infringement lawsuit by the underground thrash metal band Aftermath.[36]

First Round Knock Out, a compilation of various tracks produced and performed by Dr. Dre, was also released in 1996, with material ranging from World Class Wreckin' Cru to N.W.A to Death Row recordings.[37] Dr. Dre chose to take no part in the ongoing East Coast–West Coast hip hop rivalry of the time, instead producing for, and appearing on, several New York artists' releases, such as Nas' "Nas Is Coming", LL Cool J's "Zoom" and Jay-Z's "Watch Me".

The turning point for Aftermath came in 1998, when Jimmy Iovine, the head of Aftermath's parent label Interscope, suggested that Dr. Dre sign Eminem, a white rapper from Detroit. Dre produced three songs and provided vocals for two on Eminem's successful and controversial debut album The Slim Shady LP, released in 1999.[38] The Dr. Dre-produced lead single from that album, "My Name Is", brought Eminem to public attention for the first time, and the success of The Slim Shady LP – it reached number two on the Billboard 200 and received general acclaim from critics – revived the label's commercial ambitions and viability.[38][39][40]

Dr. Dre's second solo album, 2001, released on November 16, 1999, was considered an ostentatious return to his gangsta rap roots.[41] It was initially titled The Chronic 2000 to imply being a sequel to his debut solo effort The Chronic but was re-titled 2001 after Death Row Records released an unrelated compilation album with the title Suge Knight Represents: Chronic 2000 in May 1999. Other tentative titles included The Chronic 2001 and Dr. Dre.[42]

The album featured numerous collaborators, including Devin the Dude, Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, Xzibit, Nate Dogg, Eminem, Knoc-turn'al, King T, Defari, Kokane, Mary J. Blige and new protégé Hittman, as well as co-production between Dre and new Aftermath producer Mel-Man. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of the website AllMusic described the sound of the album as "adding ominous strings, soulful vocals, and reggae" to Dr. Dre's style.[41] The album was highly successful, charting at number two on the Billboard 200 charts[43] and has since been certified six times platinum,[24] validating a recurring theme on the album: Dr. Dre was still a force to be reckoned with, despite the lack of major releases in the previous few years. The album included popular hit singles "Still D.R.E." and "Forgot About Dre", both of which Dr. Dre performed on NBC's Saturday Night Live on October 23, 1999.[44] Dr. Dre won the Grammy Award for Producer of the Year, Non-Classical in 2000,[20] and joined the Up in Smoke Tour with fellow rappers Eminem, Snoop Dogg, and Ice Cube that year as well.[45]

During the course of 2001's popularity, Dr. Dre was involved in several lawsuits. Lucasfilm Ltd., the film company behind the Star Wars film franchise, sued him over the use of the THX-trademarked "Deep Note".[46] The Fatback Band also sued Dr. Dre over alleged infringement regarding its song "Backstrokin'" in his song "Let's Get High" from the 2001 album; Dr. Dre was ordered to pay $1.5 million to the band in 2003.[47] French jazz musician Jacques Loussier sued Aftermath for $10 million in March 2002, claiming that the Dr. Dre-produced Eminem track "Kill You" plagiarized his composition "Pulsion".[48][49] The online music file-sharing company Napster also settled a lawsuit with him and metal band Metallica in mid-2001, agreeing to block access to certain files that artists do not want to have shared on the network.[50]

2000–2010: Focus on production and Detox[편집]

Following the success of 2001, Dr. Dre focused on producing songs and albums for other artists. He co-produced six tracks on Eminem's landmark Marshall Mathers LP, including the Grammy-winning lead single, "The Real Slim Shady". The album itself earned a Grammy and proved to be the fastest-selling rap album of all time, moving 1.76 million units in its first week alone.[51] He produced the single "Family Affair" by R&B singer Mary J. Blige for her album No More Drama in 2001.[52] He also produced "Let Me Blow Ya Mind", a duet by rapper Eve and No Doubt lead singer Gwen Stefani[53] and signed R&B singer Truth Hurts to Aftermath in 2001.[54]

Dr. Dre produced and rapped on singer and Interscope labelmate Bilal's 2001 single "Fast Lane", which barely missed the Top 40 of the R&B charts.[55] He later assisted in the production of Bilal's second album, Love for Sale,[56] which Interscope controversially shelved because of its creative direction.[57] Dr. Dre was the executive producer of Eminem's 2002 release, The Eminem Show. He produced three songs on the album, one of which was released as a single, and he appeared in the award-winning video for "Without Me". He also produced the D.O.C.'s 2003 album Deuce, where he made a guest appearance on the tracks "Psychic Pymp Hotline", "Gorilla Pympin'" and "Judgment Day".

Another copyright-related lawsuit hit Dr. Dre in the fall of 2002, when Sa Re Ga Ma, a film and music company based in Calcutta, India, sued Aftermath Entertainment over an uncredited sample of the Lata Mangeshkar song "Thoda Resham Lagta Hai" on the Aftermath-produced song "Addictive" by singer Truth Hurts. In February 2003, a judge ruled that Aftermath would have to halt sales of Truth Hurts' album Truthfully Speaking if the company would not credit Mangeshkar.[58]

Another successful album on the Aftermath label was Get Rich or Die Tryin', the 2003 major-label debut album by Queens, New York-based rapper 50 Cent. Dr. Dre produced or co-produced four tracks on the album, including the hit single "In da Club", a joint production between Aftermath, Eminem's boutique label Shady Records and Interscope.[59] Eminem's fourth album since joining Aftermath, Encore, again saw Dre taking on the role of executive producer, and this time he was more actively involved in the music, producing or co-producing a total of eight tracks, including three singles.

In November 2004, at the Vibe magazine awards show in Los Angeles, Dr. Dre was attacked by a fan named Jimmy James Johnson, who was supposedly asking for an autograph. In the resulting scuffle, then-G-Unit rapper Young Buck stabbed the man.[60] Johnson claimed that Suge Knight, president of Death Row Records, paid him $5,000 to assault Dre in order to humiliate him before he received his Lifetime Achievement Award.[61] Knight immediately went on CBS's The Late Late Show to deny involvement and insisted that he supported Dr. Dre and wanted Johnson charged.[62] In September 2005, Johnson was sentenced to a year in prison and ordered to stay away from Dr. Dre until 2008.[63]

Dr. Dre also produced "How We Do", a 2005 hit single from rapper the Game from his album The Documentary,[64] as well as tracks on 50 Cent's successful second album The Massacre. For an issue of Rolling Stone magazine in April 2005, Dr. Dre was ranked 54th out of 100 artists for Rolling Stone magazine's list "The Immortals: The Greatest Artists of All Time". Kanye West wrote the summary for Dr. Dre, where he stated Dr. Dre's song "Xxplosive" as where he "got (his) whole sound from".[65]

In November 2006, Dr. Dre began working with Raekwon on his album Only Built 4 Cuban Linx II.[66] He also produced tracks for the rap albums Buck the World by Young Buck,[67] Curtis by 50 Cent,[68] Tha Blue Carpet Treatment by Snoop Dogg,[69] and Kingdom Come by Jay-Z.[70] Dre also appeared on Timbaland's track "Bounce", from his 2007 solo album, Timbaland Presents Shock Value alongside, Missy Elliott, and Justin Timberlake.[71] During this period, the D.O.C. stated that Dre had been working with him on his fourth album Voices through Hot Vessels, which he planned to release after Detox arrived.[72][73]

Planned but unreleased albums during Dr. Dre's tenure at Aftermath have included a full-length reunion with Snoop Dogg titled Breakup to Makeup, an album with fellow former N.W.A member Ice Cube which was to be titled Heltah Skeltah,[21] an N.W.A reunion album,[21] and a joint album with fellow producer Timbaland titled Chairmen of the Board.[74]

In 2007, Dr. Dre's third studio album, formerly known as Detox, was slated to be his final studio album.[75] Work for the upcoming album dates back to 2001,[76] where its first version was called "the most advanced rap album ever", by producer Scott Storch.[77] Later that same year, he decided to stop working on the album to focus on producing for other artists, but then changed his mind; the album had initially been set for a fall 2005 release.[78] Producers confirmed to work on the album include DJ Khalil, Nottz, Bernard "Focus" Edwards Jr.,[79] Hi-Tek,[80] J.R. Rotem,[81] RZA,[82] and Jay-Z.[83] Snoop Dogg claimed that Detox was finished, according to a June 2008 report by Rolling Stone magazine.[84]

After another delay based on producing other artists' work, Detox was then scheduled for a 2010 release, coming after 50 Cent's Before I Self Destruct and Eminem's Relapse, an album for which Dr. Dre handled the bulk of production duties.[85][86] In a Dr Pepper commercial that debuted on May 28, 2009, he premiered the first official snippet of Detox.[87][88] 50 Cent and Eminem asserted in a 2009 interview on BET's 106 & Park that Dr. Dre had around a dozen songs finished for Detox.[89]

On December 15, 2008, Dre appeared in the remix of the song "Set It Off" by Canadian rapper Kardinal Offishall (also with Pusha T); the remix debuted on DJ Skee's radio show.[90] At the beginning of 2009, Dre produced, and made a guest vocal performance on, the single "Crack a Bottle" by Eminem and the single sold a record 418,000 downloads in its first week[91] and reached the top of the Billboard Hot 100 chart on the week of February 12, 2009.[92] Along with this single, in 2009 Dr. Dre produced or co-produced 19 of 20 tracks on Eminem's album Relapse. These included other hit singles "We Made You", "Old Time's Sake", and "3 a.m." (The only track Dre did not produce was the Eminem-produced single "Beautiful".).

On April 20, 2010, "Under Pressure", featuring Jay-Z and co-produced with Scott Storch, was confirmed by Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre during an interview at Fenway Park as the album's first single.[93][94] The song leaked prior to its intended release in an unmixed, unmastered form without a chorus on June 16, 2010;[95] however, critical reaction to the song was lukewarm, and Dr. Dre later announced in an interview that the song, along with any other previously leaked tracks from Detox's recording process, would not appear on the final version of the album.[96]

Two genuine singles – "Kush", a collaboration with Snoop Dogg and fellow rapper Akon, and "I Need a Doctor" with Eminem and singer Skylar Grey – were released in the United States during November 2010 and February 2011 respectively:[97][98] the latter achieved international chart success, reaching number four on the Billboard Hot 100 and later being certified double platinum by the RIAA and the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA).[24][99] On June 25, 2010, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers honored Dr. Dre with its Founders Award for inspiring other musicians.[100][101]

2010–2020: The Planets, hiatus, Coachella, and Compton[편집]

In an August 2010 interview, Dr. Dre stated that an instrumental album titled The Planets is in its first stages of production; each song being named after a planet in the Solar System.[102] On September 3, Dr. Dre showed support to longtime protégé Eminem, and appeared on his and Jay-Z's Home & Home Tour, performing hit songs such as "Still D.R.E.", "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang", and "Crack a Bottle", alongside Eminem and another protégé, 50 Cent. Sporting an "R.I.P. Proof" shirt, Dre was honored by Eminem telling Detroit's Comerica Park to do the same. They did so, by chanting "DEEE-TOX", to which he replied, "I'm coming!"[103]

On November 14, 2011, Dre announced that he would be taking a break from music after he finished producing for artists Slim the Mobster and Kendrick Lamar. In this break, he stated that he would "work on bringing his Beats By Dre to a standard as high as Apple" and would also spend time with his family.[104] On January 9, 2012, Dre headlined the final nights of the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in April 2012.[105]

In June 2014, Marsha Ambrosius stated that she had been working on Detox, but added that the album would be known under another title .[106] In September 2014, Aftermath in-house producer Dawaun Parker confirmed the title change and stated that over 300 beats had been created for the album over the years, but few of them have had vocals recorded over them.[107]

The length of time that Detox had been recorded for, as well as the limited amount of material that had been officially released or leaked from the recording sessions, had given it considerable notoriety within the music industry.[108] Numerous release dates (including the ones mentioned above) had been given for the album over the years since it was first announced, although none of them transpired to be genuine.[109][110] Several musicians closely affiliated with Dr. Dre, including Snoop Dogg, fellow rappers 50 Cent, the Game and producer DJ Quik, had speculated in interviews that the album will never be released, due to Dr. Dre's business and entrepreneurial ventures having interfered with recording work, as well as causing him to lose motivation to record new material.[109][110][111][112]

On August 1, 2015, Dre announced that he would release what would be his final album, titled Compton. It is inspired by the N.W.A biopic Straight Outta Compton and is a compilation-style album, featuring a number of frequent collaborators, including Eminem, Snoop Dogg, Kendrick Lamar, Xzibit and the Game, among others. It was initially released on Apple Music on August 7, with a retail version releasing on August 21.[113][114] In an interview with Rolling Stone, he revealed that he had about 20 to 40 tracks for Detox but he did not release it because it did not meet his standards. Dre also revealed that he suffers from social anxiety and due to this, remains secluded and out of attention.[115]

On February 12, 2016, it was revealed that Apple would create its first original scripted television series and it would star Dr. Dre.[116] Called Vital Signs, it was set to reflect the life of Dr. Dre.[116] Dr. Dre was an executive producer on the show[117] before the show's cancellation sometime in 2017.[118] In October 2016, Sean Combs brought out Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg and others on his Bad Boy Reunion tour.[119]

In 2018, he produced 4 four songs on Oxnard by Anderson .Paak. He was the executive producer on the album. Same with Anderson .Paak's album, Ventura.

2020–present: Return to production and Super Bowl halftime show[편집]

Dr. Dre was the executive producer of Eminem's 2020 release, Music To Be Murdered By. He produced four songs on the album. He also produced two songs on the deluxe edition of the album, Side B and appeared on the song Gunz Blazing. On September 30, 2021, it was revealed that Dre would perform at the Super Bowl LVI halftime show alongside Eminem, Snoop Dogg, Mary J. Blige, and Kendrick Lamar. In December 2021, a update for the video game Grand Theft Auto Online predominantly featured Dre and added some of his previously unreleased tracks which was released as an EP, The Contract, on February 3, 2022.[120][121] Around this time, Dre announced he was collaborating with Marsha Ambrosius on Casablanco and with Mary J. Blige on an upcoming album.[122][123]

On February 13, 2022, Eminem performed at the Super Bowl LVI halftime show alongside Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Kendrick Lamar, and Mary J. Blige,[124] with surprise appearances from 50 Cent and Anderson. Paak.[125] In 2022, Dre produced the song "The King and I" a collaboration between Eminem and Ceelo Green for the 2022 biopic, Elvis.

Other ventures[편집]

Film appearances[편집]

Dr. Dre made his first on screen appearance as a weapons dealer in the 1996 bank robbery movie Set It Off.[126] In 2001, Dr. Dre also appeared in the movies The Wash and Training Day.[76] A song of his, "Bad Intentions" (featuring Knoc-Turn'Al) and produced by Mahogany, was featured on The Wash soundtrack.[127] Dr. Dre also appeared on two other songs "On the Blvd." and "The Wash" along with his co-star Snoop Dogg.

Crucial Films[편집]

| 창립 | 2007 |

|---|---|

| 창립자 | Dr. Dre |

| 산업 분야 | Film production company |

| 주요 주주 | New Line Cinema |

| 웹사이트 | crucialfilms |

In February 2007, it was announced that Dr. Dre would produce dark comedies and horror films for New Line Cinema-owned company Crucial Films, along with longtime video director Phillip Atwell. Dr. Dre announced "This is a natural switch for me, since I've directed a lot of music videos, and I eventually want to get into directing."[128] Along with fellow member Ice Cube, Dr. Dre produced Straight Outta Compton (2015), a biographical film about N.W.A.[129]

Entrepreneurship[편집]

In July 2008, Dr. Dre released his first brand of headphones, Beats by Dr. Dre. The line consisted of Beats Studio, a circumaural headphone; Beats Tour, an in-ear headphone; Beats Solo & Solo HD, a supra-aural headphone; Beats Spin; Heartbeats by Lady Gaga, also an in-ear headphone; and Diddy Beats.[130] In late 2009, Hewlett-Packard participated in a deal to bundle Beats By Dr. Dre with some HP laptops and headsets.[131] HP and Dr. Dre announced the deal on October 9, 2009, at a press event. An exclusive laptop, known as the HP ENVY 15 Beats limited edition, was released for sale October 22. In May 2014, technology giant Apple purchased the Beats brand for $3 billion.[132] The deal made Dr. Dre the "richest man in hip hop".[133] Dr. Dre became an Apple employee in an executive role,[134][135] and worked with Apple for years.[136]

Philanthropy[편집]

During May 2013, Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine donated a $70 million endowment to the University of Southern California to create the USC Jimmy Iovine and Andre Young Academy for Arts, Technology and the Business of Innovation. The goal of the academy has been stated as "to shape the future by nurturing the talents, passions, leadership and risk-taking of uniquely qualified students who are motivated to explore and create new art forms, technologies, and business models." The first class of the academy began in September 2014.[137]

In June 2017, it was announced that Dr. Dre has committed $10 million to the construction of a performing arts center for the new Compton High School. The center will encompass creative resources and a 1,200-seat theater, and is expected to break ground in 2020. The project is a partnership between Dr. Dre and the Compton Unified School District.[138]

Commercial endorsements[편집]

In 2002 and 2003, Dr. Dre appeared in TV commercials for Coors Light beer.[139]

Beginning in 2009, Dr. Dre appeared in TV commercials that also featured his Beats Electronics product line. A 2009 commercial for the Dr Pepper soft drink had Dr. Dre DJing with Beats headphones and playing a brief snippet off the never-released Detox album.[87][88] In 2010, Dr. Dre had a cameo in a commercial for HP laptops that featured a plug for Beats Audio.[139] Then in 2011, the Chrysler 300S "Imported from Detroit" ad campaign had a commercial narrated by Dr. Dre and including a plug for Beats Audio.[140]

Dr. Dre started Burning Man rumors[편집]

An urban legend surfaced in 2011 when a Tumblr blog titled Dr. Dre Started Burning Man[141][142] began promulgating the notion that the producer, rapper and entrepreneur had discovered Burning Man in 1995 during a music video shoot and offered to cover the cost of the event's permit from the Nevada Bureau of Land Management under an agreement with the festival's organizers that he could institute an entrance fee system, which had not existed before his participation.[143][144] This claim was supported by an alleged letter from Dre to Nicole Threatt Young that indicated that Dre had shared his experience witnessing the Burning Man festival with her.[145][146]

Business Insider mentions the portion of the letter where Dr. Dre purportedly states "someone should get behind this ... and make some money off these fools" and compares Dr. Dre's potential entrepreneurial engagement with Burning Man as a parallel to Steve Jobs' efforts to centralize and profit from the otherwise unorganized online music industry.[147] According to Salon, Dr. Dre's ethos seems to be aligned with seven of the ten principles of the Burning Man community: "radical self-reliance, radical self-expression, communal effort, civic responsibility, leaving no trace, participation and immediacy."[143]

Musical influences and style[편집]

The space, about the size of a college dorm room, is splattered with papers, ideas scribbled down in black ink. Nuthin' but G thangs waiting to happen. Those that don't happen end up in a round, purple L.A. Lakers trash can. A kitchen, red and stainless steel like a '50s diner, adjoins the control room

Production style[편집]

Dre is noted for his evolving production style, while always keeping in touch with his early musical sound and re-shaping elements from previous work. At the beginning of his career as a producer for the World Class Wreckin Cru with DJ Alonzo Williams in the mid-1980s, his music was in the electro-hop style pioneered by The Unknown DJ, and that of early hip-hop groups like the Beastie Boys and Whodini.

From Straight Outta Compton on, Dre uses live musicians to replay old melodies rather than sampling them. With Ruthless Records, collaborators included guitarist Mike "Crazy Neck" Sims, multi-instrumentalist Colin Wolfe, DJ Yella and sound engineer Donovan "The Dirt Biker" Sound. Dre is receptive of new ideas from other producers, one example being his fruitful collaboration with Above the Law's producer Cold 187um while at Ruthless. Cold 187 um was at the time experimenting with 1970s P-Funk samples (Parliament, Funkadelic, Bootsy Collins, George Clinton etc.), that Dre also utilized. Dre has since been accused of "stealing" the concept of G-funk from Cold 187 um.[149]

Upon leaving Ruthless and forming Death Row Records in 1991, Dre called on veteran West Coast DJ Chris "The Glove" Taylor and sound engineer Greg "Gregski" Royal, along with Colin Wolfe, to help him on future projects. His 1992 album The Chronic is thought to be one of the most well-produced hip-hop albums of all time.[150][151][152] Musical themes included hard-hitting synthesizer solos played by Wolfe, bass-heavy compositions, background female vocals and Dre fully embracing 1970s funk samples. Dre used a minimoog synth to replay the melody from Leon Haywood's 1972 song "I Wanna Do Somethin' Freaky to You" for the Chronic's first single "Nuthin' but a 'G' Thang" which became a global hit. For his new protégé Snoop Doggy Dogg's album Doggystyle, Dre collaborated with then 19-year-old producer Daz Dillinger, who received co-production credits on songs "Serial Killa" and "For all My Niggaz & Bitches", The Dramatics bass player Tony "T. Money" Green, guitarist Ricky Rouse, keyboardists Emanuel "Porkchop" Dean and Sean "Barney Rubble" Thomas and engineer Tommy Daugherty, as well as Warren G and Sam Sneed, who are credited with bringing several samples to the studio.[153]

The influence of The Chronic and Doggystyle on the popular music of the 1990s went not only far beyond the West Coast, but beyond hip-hop as a genre. Artists as diverse as Master P ("Bout It, Bout It"), George Michael ("Fastlove"), Mariah Carey ("Fantasy"), Adina Howard ("Freak Like Me"), Luis Miguel ("Dame"), and The Spice Girls ("Say You'll Be There") used G-funk instrumentation in their songs.[154][155] Bad Boy Records producer Chucky Thompson stated in the April 2004 issue of XXL magazine that the sound of Doggystyle and The Chronic was the basis for the Notorious B.I.G.'s 1995 hit single "Big Poppa":

At that time, we were listening to Snoop's album. We knew what was going on in the West through Dr. Dre. Big just knew the culture, he knew what was going on with hip-hop. It was more than just New York, it was all over.[156]

In 1994, starting with the Murder was the Case soundtrack, Dre attempted to push the boundaries of G-funk further into a darker sound. In songs such as "Murder was the Case" and "Natural Born Killaz", the synthesizer pitch is higher and the drum tempo is slowed down to 91 BPM[157] (87 BPM in the remix) to create a dark and gritty atmosphere. Percussion instruments, particularly sleigh bells, are also present. Dre's frequent collaborators from this period included Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania natives Stuart "Stu-B-Doo" Bullard, a multi-instrumentalist from the Ozanam Strings Orchestra,[158] Sam Sneed, Stephen "Bud'da" Anderson,[159] and percussionist Carl "Butch" Small. This style of production has been influential far beyond the West Coast. The beat for the Houston-based group Geto Boys 1996 song "Still" follows the same drum pattern as "Natural Born Killaz" and Eazy E's "Wut Would U Do" (a diss to Dre) is similar to the original "Murder was the Case" instrumental. This style of production is usually accompanied by horror and occult-themed lyrics and imagery, being crucial to the creation of horrorcore.

By 1996, Dre was again looking to innovate his sound. He recruited keyboardist Camara Kambon to play the keys on "Been There, Done That", and through Bud'da and Sam Sneed he was introduced to fellow Pittsburgh native Melvin "Mel-Man" Bradford. At this time, he also switched from using the E-mu SP-1200 to the Akai MPC3000 drum kit and sampler, which he still uses today. Beginning with his 1996 compilation Dr. Dre Presents the Aftermath, Dre's production has taken a less sample-based approach, with loud, layered snare drums dominating the mix, while synthesizers are still omnipresent. In his critically acclaimed second album, 2001, live instrumentation takes the place of sampling, a famous example being "The Next Episode", in which keyboardist Camara Kambon re-played live the main melody from David McCallum's 1967 jazz-funk work "The Edge". For every song on 2001, Dre had a keyboardist, guitarist and bassist create the basic parts of the beat, while he himself programmed the drums, did the sequencing and overdubbing and added sound effects, and later mixed the songs. During this period, Dre's signature "west coast whistle" riffs are still present albeit in a lower pitch, as in "Light Speed", "Housewife", "Some L.A. Niggaz" and Eminem's "Guilty Conscience" hook. The sound of "2001" had tremendous influence on hip-hop production, redefining the West Coast's sound and expanding the G-funk of the early 1990s. To produce the album, Dre and Mel-Man relied on the talents of Scott Storch and Camara Kambon on the keys, Mike Elizondo and Colin Wolfe on bass guitar, Sean Cruse on lead guitar and sound engineers Richard "Segal" Huredia and Mauricio "Veto" Iragorri.[160]

From the mid-2000s, Dr. Dre has taken on a more soulful production style, using more of a classical piano instead of a keyboard, and having claps replace snares, as evidenced in songs such as Snoop Dogg's "Imagine" and "Boss' Life", Busta Rhymes' "Get You Some" and "Been Through the Storm", Stat Quo's "Get Low" and "The Way It Be", Jay-Z's "Lost One", Nas' "Hustlers", and several beats on Eminem's Relapse album. Soul and R&B pianist Mark Batson, having previously worked with The Dave Matthews Band, Seal and Maroon 5 has been credited as the architect of this sound. Besides Batson, Aftermath producer and understudy of Dre's, Dawaun Parker, who has named Q-Tip and J Dilla as his primary influences, is thought to be responsible for giving Dre's newest beats an East Coast feel.[161]

Production equipment[편집]

Dr. Dre has said that his primary instrument in the studio is the Akai MPC3000, a drum machine and sampler, and that he often uses as many as four or five to produce a single recording. He cites 1970s funk musicians such as George Clinton, Isaac Hayes and Curtis Mayfield as his primary musical influences. Unlike most rap producers, he tries to avoid samples as much as possible, preferring to have studio musicians re-play pieces of music he wants to use, because it allows him more flexibility to change the pieces in rhythm and tempo.[162] In 2001 he told Time magazine, "I may hear something I like on an old record that may inspire me, but I'd rather use musicians to re-create the sound or elaborate on it. I can control it better."[163]

Other equipment he uses includes the E-mu SP-1200 drum machine and other keyboards from such manufacturers as Korg, Rhodes, Wurlitzer, Moog, and Roland.[164] Dr. Dre also stresses the importance of equalizing drums properly, telling Scratch magazine in 2004 that he "used the same drum sounds on a couple of different songs on one album before but you'd never be able to tell the difference because of the EQ."[162] Dr. Dre also uses the digital audio workstation Pro Tools and uses the software to combine hardware drum machines and vintage analog keyboards and synthesizers.[162][165]

After founding Aftermath Entertainment in 1996, Dr. Dre took on producer Mel-Man as a co-producer, and his music took on a more synthesizer-based sound, using fewer vocal samples (as he had used on "Lil' Ghetto Boy" and "Let Me Ride" on The Chronic, for example). Mel-Man has not shared co-production credits with Dr. Dre since approximately 2002, but fellow Aftermath producer Focus has credited Mel-Man as a key architect of the signature Aftermath sound.[166]

In 1999, Dr. Dre started working with Mike Elizondo, a bassist, guitarist, and keyboardist who has also produced, written and played on records for female singers such as Poe, Fiona Apple and Alanis Morissette,[167] In the past few years Elizondo has since worked for many of Dr. Dre's productions.[168][169] Dr. Dre also told Scratch magazine in a 2004 interview that he has been studying piano and music theory formally, and that a major goal is to accumulate enough musical theory to score movies. In the same interview he stated that he has collaborated with famed 1960s songwriter Burt Bacharach by sending him hip hop beats to play over, and hopes to have an in-person collaboration with him in the future.[162]

Work ethic[편집]

Dr. Dre has stated that he is a perfectionist and is known to pressure the artists with whom he records to give flawless performances.[162] In 2006, Snoop Dogg told the website Dubcnn.com that Dr. Dre had made new artist Bishop Lamont re-record a single bar of vocals 107 times.[170] Dr. Dre has also stated that Eminem is a fellow perfectionist, and attributes his success on Aftermath to his similar work ethic.[162] He gives a lot of input into the delivery of the vocals and will stop an MC during a take if it is not to his liking.[171] However, he gives MCs that he works with room to write lyrics without too much instruction unless it is a specifically conceptual record, as noted by Bishop Lamont in the book How to Rap.[172]

A consequence of his perfectionism is that some artists who initially sign deals with Dr. Dre's Aftermath label never release albums. In 2001, Aftermath released the soundtrack to the movie The Wash, featuring a number of Aftermath acts such as Shaunta, Daks, Joe Beast and Toi. To date, none have released full-length albums on Aftermath and have apparently ended their relationships with the label and Dr. Dre. Other noteworthy acts to leave Aftermath without releasing albums include King Tee, 2001 vocalist Hittman, Joell Ortiz, Raekwon and Rakim.[173]

Collaborators and co-producers[편집]

Over the years, word of other collaborators who have contributed to Dr. Dre's work has surfaced. During his tenure at Death Row Records, it was alleged that Dr. Dre's stepbrother Warren G and Tha Dogg Pound member Daz made many uncredited contributions to songs on his solo album The Chronic and Snoop Doggy Dogg's album Doggystyle (Daz received production credits on Snoop's similar-sounding, albeit less successful album Tha Doggfather after Young left Death Row Records).[174]

It is known that Scott Storch, who has since gone on to become a successful producer in his own right, contributed to Dr. Dre's second album 2001; Storch is credited as a songwriter on several songs and played keyboards on several tracks. In 2006 he told Rolling Stone:

"At the time, I saw Dr. Dre desperately needed something," Storch says. "He needed a fuel injection, and Dr. Dre utilized me as the nitrous oxide. He threw me into the mix, and I sort of tapped on a new flavor with my whole piano sound and the strings and orchestration. So I'd be on the keyboards, and Mike [Elizondo] was on the bass guitar, and Dr. Dre was on the drum machine".[175]

Current collaborator Mike Elizondo, when speaking about his work with Young, describes their recording process as a collaborative effort involving several musicians. In 2004 he claimed to Songwriter Universe magazine that he had written the foundations of the hit Eminem song "The Real Slim Shady", stating, "I initially played a bass line on the song, and Dr. Dre, Tommy Coster Jr. and I built the track from there. Eminem then heard the track, and he wrote the rap to it."[169] This account is essentially confirmed by Eminem in his book Angry Blonde, stating that the tune for the song was composed by a studio bassist and keyboardist while Dr. Dre was out of the studio but Young later programmed the song's beat after returning.[176]

A group of disgruntled former associates of Dr. Dre complained that they had not received their full due for work on the label in the September 2003 issue of The Source. A producer named Neff-U claimed to have produced the songs "Say What You Say" and "My Dad's Gone Crazy" on The Eminem Show, the songs "If I Can't" and "Back Down" on 50 Cent's Get Rich or Die Tryin', and the beat featured on Dr. Dre's commercial for Coors beer.[173]

Although Young studies piano and music theory, he serves as more of a conductor than a musician himself, as Josh Tyrangiel of Time magazine has noted:

Every Dre track begins the same way, with Dre behind a drum machine in a room full of trusted musicians. (They carry beepers. When he wants to work, they work.) He'll program a beat, then ask the musicians to play along; when Dre hears something he likes, he isolates the player and tells him how to refine the sound. "My greatest talent," Dre says, "is knowing exactly what I want to hear."[163]

Although Snoop Dogg retains working relationships with Warren G and Daz, who are alleged to be uncredited contributors on the hit albums The Chronic and Doggystyle, he states that Dr. Dre is capable of making beats without the help of collaborators, and that he is responsible for the success of his numerous albums.[177] Dr. Dre's prominent studio collaborators, including Scott Storch, Elizondo, Mark Batson and Dawaun Parker, have shared co-writing, instrumental, and more recently co-production credits on the songs where he is credited as the producer.

Anderson .Paak also praised Dr. Dre in a 2016 interview with Music Times, telling the publication that it was a dream come true to work with Dre.[178]

Ghostwriters[편집]

It is acknowledged that most of Dr. Dre's raps are written for him by others, though he retains ultimate control over his lyrics and the themes of his songs.[179] As Aftermath producer Mahogany told Scratch: "It's like a class room in [the booth]. He'll have three writers in there. They'll bring in something, he'll recite it, then he'll say, 'Change this line, change this word,' like he's grading papers."[180] As seen in the credits for tracks Young has appeared on, there are often multiple people who contribute to his songs (although often in hip hop many people are officially credited as a writer for a song, even the producer).

In the book How to Rap, RBX explains that writing The Chronic was a "team effort"[181] and details how he ghostwrote "Let Me Ride" for Dre.[181] In regard to ghostwriting lyrics he says, "Dre doesn't profess to be no super-duper rap dude – Dre is a super-duper producer".[181] As a member of N.W.A, the D.O.C. wrote lyrics for him while he stuck with producing.[21] New York City rapper Jay-Z ghostwrote lyrics for the single "Still D.R.E." from Dr. Dre's album 2001.[42]

Personal life[편집]

On December 15, 1981, when Dre was 16 years old and his then-girlfriend Cassandra Joy Greene was 15 years old, the two had a son named Curtis, who was brought up by Greene and first met Dre 20 years later.[182] Curtis performed as a rapper under the name Hood Surgeon.[183]

In 1983, Dre and Lisa Johnson had a daughter named La Tanya Danielle Young.[184][185] Dre and Johnson have three daughters together.[186]

In 1988, Dre and Jenita Porter had a son named Andre Young Jr. In 1990, Porter sued Dre, seeking $5,000 of child support per month.[187] On August 23, 2008, Andre died at the age of 20 from an overdose of heroin and morphine[188] at his mother's Woodland Hills home.[187]

From 1987 to 1996, Dre dated singer Michel'le, who frequently contributed vocals to Ruthless Records and Death Row Records albums.[189] In 1991, they had a son named Marcel.[190][191]

In 1996, Dre married Nicole (née Plotzker) Threatt, who was previously married to basketball player Sedale Threatt.[192][185] They have two children together: a son named Truice (born 1997) and a daughter named Truly (born 2001).[193]

In 2001, Dre earned a total of about US$52 million from selling part of his share of Aftermath Entertainment to Interscope Records and his production of such hit songs that year as "Family Affair" by Mary J. Blige. Rolling Stone magazine thus named him the second highest-paid artist of the year.[52] Dr. Dre was ranked 44th in 2004 from earnings of $11.4 million, primarily from production royalties from such projects as albums from G-Unit and D12 and the single "Rich Girl" by singer Gwen Stefani and rapper Eve.[194] Forbes estimated his net worth at US$270 million in 2012.[195] The same publication later reported that he acquired US$110 million via his various endeavors in 2012, making him the highest–paid artist of the year.[196] Income from the 2014 sale of Beats to Apple, contributing to what Forbes termed "the biggest single-year payday of any musician in history", made Dr. Dre the world's richest musical performer of 2015.[197]

In 2014, Dre purchased a $40 million home in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles from its previous owners, NFL player Tom Brady and supermodel Gisele Bundchen.[198]

It was reported that Dre suffered a brain aneurysm on January 5, 2021,[199] and that he was admitted to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center's ICU in Los Angeles, California.[200] Hours after his admission to the hospital, Dre's home was targeted for an attempted burglary.[201] He eventually received support from LeBron James, Martin Lawrence, LL Cool J, Missy Elliott, Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, 50 Cent, Ellen DeGeneres, Ciara, her husband Russell Wilson, T.I., Quincy Jones and others.[202][203] In February, he was released with a following message on Instagram: "Thanks to my family, friends and fans for their interest and well wishes. I'm doing great and getting excellent care from my medical team. I will be out of the hospital and back home soon. Shout out to all the great medical professionals at Cedars. One Love!!"[204][205]

Controversies and legal issues[편집]

Violence against women[편집]

Dre has been accused of multiple incidents of violence against women.[206] On January 27, 1991, at a music industry party at the Po Na Na Souk club in Hollywood, Dr. Dre assaulted television host Dee Barnes of the Fox television program Pump it Up!, following an episode of the show. Barnes had interviewed NWA, which was followed by an interview with Ice Cube in which Cube mocked NWA.[207] Barnes filed a $22.7 million lawsuit in response to the incident.[208] Subsequently, Dr. Dre was fined $2,500, given two years' probation, ordered to undergo 240 hours of community service, and given a spot on an anti-violence public service announcement on television.[209][210] The civil suit was settled out of court.[211] Barnes stated that he "began slamming her face and the right side of her body repeatedly against a wall near the stairway". Dr. Dre later commented: "People talk all this shit, but you know, somebody fucks with me, I'm gonna fuck with them. I just did it, you know. Ain't nothing you can do now by talking about it. Besides, it ain't no big thing – I just threw her through a door."[206]

In March 2015, Michel'le, the mother of one of Dre's children, accused him of subjecting her to domestic violence during their time together as a couple, but did not initiate legal action.[212][213] Their abusive relationship is portrayed in her 2016 biopic Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge & Michel'le.[214][215]

Interviewed by Ben Westhoff for the book Original Gangstas: the Untold Story of Dr Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Tupac Shakur, and the Birth of West Coast Rap, Lisa Johnson stated that Dre beat her many times, including while she was pregnant.[184] She was granted a restraining order against him.[216]

Former labelmate Tairrie B claimed that Dre assaulted her at a post-Grammy party in 1990, in response to her track "Ruthless Bitch".[217]

During press for the 2015 film Straight Outta Compton, questions about the portrayal and behavior of Dre and other prominent figures in the rap community about violence against women – and the question about its absence in the film – were raised.[218] The discussion about the film led to Dre addressing his past behavior in the press. In August 2015, in an interview with Rolling Stone,[219] Dre lamented his abusive past, saying, "I made some fucking horrible mistakes in my life. I was young, fucking stupid. I would say all the allegations aren't true—some of them are. Those are some of the things that I would like to take back. It was really fucked up. But I paid for those mistakes, and there's no way in hell that I will ever make another mistake like that again."[115][220]

In a statement to The New York Times on August 21, 2015, exactly two weeks after his album, Compton, was released, Dre again addressed his abusive past, stating, "25 years ago I was a young man drinking too much and in over my head with no real structure in my life. However, none of this is an excuse for what I did. I've been married for 19 years and every day I'm working to be a better man for my family, seeking guidance along the way. I'm doing everything I can so I never resemble that man again. ... I apologize to the women I've hurt. I deeply regret what I did and know that it has forever impacted all of our lives."[218]

In the 2017 film, The Defiant Ones, Dr. Dre explained about the Dee Barnes incident again, "This was a very low point in my life. I've done a lot of stupid shit in my life. A lot of things I wish I could go and take back. I've experienced abuse. I've watched my mother get abused. So there's absolutely no excuse for it. No woman should ever be treated that way. Any man that puts his hands on a female is a fucking idiot. He's out of his fucking mind, and I was out of my fucking mind at the time. I fucked up, I paid for it, I'm sorry for it, and I apologize for it. I have this dark cloud that follows me, and it's going to be attached to me forever. It's a major blemish on who I am as a man."[221]

Second divorce[편집]

Dre's wife, Nicole Plotzker-Young, filed for divorce in June 2020, citing irreconcileable differences.[222][223][224] In November 2020, she filed legal claims that Dre engaged in verbal violence and infidelity during their marriage.[225][226] She also stated that he tore up their prenuptial agreement that he wanted her to sign out of anger.[227] Dre's representative responded, calling her claims of infidelity and violence in their marriage "false".[228] Before being released from the Cedar-Sinai Medical Center, he was ordered to pay Plotzker-Young $2 million in temporary spousal support.[229] Between the spring and summer of the year, Dre was ordered by the Los Angeles County judge to pay his ex-wife over $300,000 a month in spousal support.[230] The $2 million extension request was also dismissed, due to insufficient claims.[231] In July 2021, Dr. Dre was ordered by the Los Angeles Superior Court Judge to pay an additional $293,306 a month to estranged wife in spousal support starting August 1 until she decides to remarry or "further order of the Court".[232] Then, in August, the judge denied his wife's request for a protective order, due to her being afraid of Dre after a snippet leaked on Instagram of him rapping about the divorce proceedings and his possible brain aneurysm earlier that February; in this snippet, he called his wife a "greedy bitch".[233][234][235] In mid-October, Dr. Dre was served more divorce papers, during his grandmother's funeral.[236][237] That same month, Dre was officially deemed "single" by the judge.[238] The financial owings in this case included expenses of Dre's Malibu, Palisades and Hollywood Hills homes, but not his stock in past ownership of Beats Electronics, prior to its sale to Apple in 2014.[239][240] As of December 2021, the divorce proceedings have entered its final stages.[241] On December 28, the divorce was settled with Dre keeping most of his assets and income due to the prenuptial agreement, although he would have to pay a 9-figure settlement within one year.[242]

Other[편집]

Dre pleaded guilty in October 1992 in a case of battery of a police officer and was convicted on two additional battery counts stemming from a brawl in the lobby of the New Orleans hotel in May 1991.[243]

On January 10, 1994, Dre was arrested after leading police on a 90 mph pursuit through Beverly Hills in his 1987 Ferrari. It was revealed Dr. Dre had a blood alcohol of 0.16, twice the state's legal limit. The conviction violated the conditions of parole following Dre's battery conviction; in September 1994 he was sentenced to eight months in prison.[244]

On April 4, 2016, TMZ and the New York Daily News reported that Suge Knight had accused Dre and the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department of a kill-for-hire plot in the 2014 shooting of Knight in club 1 OAK.[245][246] Three months later, in July, Dre was reportedly detained by police after confronting a next-door neighbor in Malibu about a test drive.[247] It was also alleged that Dre brandished a handgun on the neighbor, but no evidence would be linked and Dre was soon released.[248]

In August 2021, Dr. Dre's oldest daughter LaTanya Young spoke out about being homeless and unable to support her four children. She is currently working for UberEats and DoorDash, and she also works at warehouse jobs. She is living in debt in her SUV while her children are living with friends. Dr. Dre has allegedly stopped supporting LaTanya financially since January 2020 because she has "spoken about him in the press".[249][250]

Discography[편집]

Studio albums[편집]

- The Chronic (1992)

- 2001 (1999)

- Compton (2015)

EPs[편집]

- The Contract (2021)

Soundtrack albums[편집]

- The Wash (2001)

Collaboration albums[편집]

with World Class Wreckin' Cru

- World Class (1985)

- Rapped in Romance (1986)

with N.W.A.

- N.W.A. and the Posse (1987)

- Straight Outta Compton (1988)

- 100 Miles and Runnin' (1990)

- Niggaz4Life (1991)

Awards and nominations[편집]

BET Hip Hop Awards[편집]

| 연도 | 후보 | 수상 부문 | 결과 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Himself | Hustler of the Year | 수상 |

| 2015 | 후보 | ||

| 2016[251] | Producer of the Year | 후보 | |

| Compton | Album of the Year | 후보 |

Grammy Awards[편집]

Dr. Dre has won six Grammy Awards. Three of them are for his production work.[252][253][254]

MTV Video Music Awards[편집]

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | "Nuthin' But a 'G' Thang" | Best Rap Video | 후보 |

| 1994 | "Let Me Ride" | 후보 | |

| 1995 | "Keep Their Heads Ringin'" | 수상 | |

| 1997 | "Been There, Done That" | 후보 | |

| Best Choreography in a Video | 후보 | ||

| 1999 | "My Name Is" | Best Direction | 후보 |

| "Guilty Conscience" | Breakthrough Video | 후보 | |

| 2000 | "The Real Slim Shady" | Best Direction in a Video | 후보 |

| 2000 | "Forgot About Dre" | Best Rap Video | 수상 |

| 2001 | "Stan" | Best Direction in a Video | 후보 |

| 2009 | "Nuthin' But a 'G' Thang" | Best Video (That Should Have Won a Moonman) | 후보 |

Filmography[편집]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Niggaz4Life: The Only Home Video | Himself | Documentary |

| 1996 | Set It Off | Black Sam | Minor role |

| 1999 | Whiteboyz | Don Flip Crew #1 | Minor role |

| 2000 | Up in Smoke Tour | Himself | Concert film |

| 2001 | Training Day | Paul | Minor role |

| 2001 | The Wash | Sean | Main role |

| 2015 | Unity[255] | Narrator | Documentary |

| 2017 | The Defiant Ones[256] | Himself | Documentary |

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 50 Cent: Bulletproof | Grizz | Voice role and likeness |

| 2020 | Grand Theft Auto Online: The Cayo Perico Heist[257] | Himself | Voice role and likeness; cameo |

| 2021 | Grand Theft Auto Online: The Contract[258] | Voice role and likeness; update also features new music created by Dre for the game |

| Year | Title | Portrayed by | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | Corey Hawkins | Biographical film about N.W.A |

| 2016 | Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge & Michel'le | Chris Hamilton | Biographical film about Michel'le |

| 2017 | All Eyez on Me | Harold Moore[259] | Biographical film about Tupac Shakur |

References[편집]

- ↑ “Dr. Dre: 'I apologize to the women I've hurt'”. CBS News. 2021년 12월 29일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 1쪽.

- ↑ Naoreen, Nuzhat (2013년 2월 15일). “Monitor: Feb. 22 2013”. 《Entertainment Weekly》. 2020년 1월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 6–8, 25쪽.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 9쪽.

- ↑ *Westhoff, Ben (2016). 《Original Gangstas: Tupac Shakur, Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and the Birth of West Coast Rap》 (e-book). New York: Hachette Book Group. 21쪽. ISBN 9780316344869. OCLC 964683937.

- ↑ Ro, Ronin (November 1992). “Moving Target”. 《The Source》. 38호. 38–44쪽. 2020년 1월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 10쪽.

- ↑ Kenyatta 2001, 14쪽.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 2쪽.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 18–19쪽.

- ↑ Kenyatta 2001, 15쪽.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 14쪽.

- ↑ Williams, Justin A. (2012년 7월 10일). 〈Dr. Dre [Young, Andre Romelle]〉. 《Grove Music Online》. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2224243. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. 2020년 1월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 23쪽.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. “'Concrete Roots' > Overview”. 《AllMusic》. 2021년 12월 30일에 확인함.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 26쪽.

- ↑ Kenyatta 2001, 14–15쪽.

- ↑ Ro 2007, 17쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 사 아 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2016). “Dr. Dre – Biography”. 《AllMusic》. 2021년 12월 30일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 “Q&A w/The D.O.C.: From Ruthless to Death Row”. 《ThaFormula.com》. 2004. 2010년 4월 9일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “Concrete Roots - Dr. Dre - Songs, Reviews, Credits”. 《AllMusic》. 2020년 1월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Huey, Steve. [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/album/r70573 “'The Chronic' – Overview”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2007년 9월 22일에 확인함. - ↑ 가 나 다 라 “Gold & Platinum Dr. Dre”. Recording Industry Association of America. 2015년 12월 31일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 4일에 확인함.

- ↑ [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p26119 “Dr. Dre – Grammy Awards”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 2월 17일에 확인함. - ↑ Holden, Stephen (1994년 1월 14일). “The Pop Life”. 《The New York Times》. 2008년 3월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/album/r185654 “"Doggystyle" – Overview”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 2월 15일에 확인함. - ↑ [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p26119 “Dr. Dre – Awards”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2009년 1월 1일에 확인함. - ↑ “Bone Broken: 2Pac Takes Over At No. 1”. 《Billboard》. 108권 28호. July 1996. 118쪽. ISSN 0006-2510. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Huey, Steve (2003). [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p279843 “Suge Knight – Biography”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 2월 17일에 확인함. - ↑ Huey, Steve. “Blackstreet – Biography”. 《AllMusic》. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Arnold, Paul W. (2010년 5월 27일). “Danny Boy Tells All About Death Row Years, Part Two”. 《HipHopDX》. 2014년 7월 14일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/album/r243986 “'Dr. Dre Presents...The Aftermath' – Overview”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 2월 17일에 확인함. - ↑ 〈Dana Carvey/Dr. Dre〉. 《Saturday Night Live》. 제 22-4회. 1996년 10월 26일. NBC. 2008년 3월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Birchmeier, Jason. [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p276628 “The Firm – Biography”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2007년 9월 22일에 확인함. - ↑ Tsiolis v. Interscope. Records. Inc., 946 F.Supp. 1344, 1349 (N.D.III. 1996).

- ↑ Henderson, Alex. [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/album/r234875 “First Round Knock Out > Overview”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 6월 26일에 확인함. - ↑ 가 나 Ankeny, Jason; Torreano, Bradley (2006). [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p347307 “Eminem – Biography”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2007년 9월 22일에 확인함. - ↑ “The Slim Shady LP – Eminem – Awards”. 《AllMusic》. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Adaso, Henry. “Biography: Dr. Dre”. About.com. 2013년 3월 26일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ 가 나 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (1999). [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/album/r441973 “"2001" – Overview”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 2월 17일에 확인함. - ↑ 가 나 Gill, John (1999년 10월 13일). “Dr. Dre Changes Album Title... Again”. 《MTV News》. 2000년 1월 23일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p26119 “Dr. Dre – Billboard Albums”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2007년 9월 22일에 확인함. - ↑ 〈Norm Macdonald/Dr. Dre〉. 《Saturday Night Live》. 제 24-3회. 1999년 10월 23일. NBC. 2008년 3월 7일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Pareles, Jon (2000년 7월 17일). “Four Hours Of Swagger From Dr. Dre And Friends”. 《Slate》. 2022년 6월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Johnson, Tina (2000년 4월 19일). “Dr. Dre Sued By Lucasfilm”. 《MTV News》. 2000년 5월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2022년 6월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Moss, Corey (2003년 5월 7일). “Jury Orders Dr. Dre To Pay $1.5 Million For Copyright Infringement”. MTV News. 2003년 6월 1일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Dansby, Andrew (2002년 4월 3일). “Composer Addresses Eminem Suit”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2022년 6월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Eminem sued by jazz star”. 《BBC News》. 2002년 3월 31일. 2018년 5월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Napster settles suits”. 《CNN Money》. 2001년 7월 12일. 2002년 2월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Eminem Bounces Britney From Top Spot”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2000년 5월 31일. 2008년 5월 3일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ 가 나 LaFranco, Robert; Binelli, Mark; Goodman, Fred (2002년 6월 13일). “U2, Dre Highest Earning Artists”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2008년 2월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Moss, Corey; Gottlieb, Meredith (2001년 3월 15일). “Eve, Gwen Stefani Bust Loose In Video”. MTV News. 2001년 10월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2002년 4월 9일). “Truth Hurts”. 《You Hear It First》 (MTV News). 2002년 4월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2008년 6월 26일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reeves, Mosi (2017년 6월 29일). “25 Greatest Songs Produced by Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2020년 7월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kellman, Andy (n.d.). “Bilal”. 《AllMusic》. 2020년 7월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gray, Arielle (2018년 11월 26일). “Bilal Brings Creative Resistance To The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum”. The ARTery. WBUR. 2020년 7월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kaufman, Gil (2003년 2월 4일). “Judge Rules Truth Hurts' Album Must Be Pulled Or Stickered”. 《MTV News》. 2003년 2월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Birchmeier, Jason (2007년 9월 11일). [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/artist/p372609 “50 Cent – Biography”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 5월 24일에 확인함. - ↑ Moss, Corey (2004년 11월 16일). “Warrant Issued For Young Buck In Vibe Awards Stabbing”. 《MTV News》. 2004년 11월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Smith, Pam (2006년 11월 27일). “Dr. Dre Puncher Snitches On Suge Knight”. 《SOHH》. 2006년 11월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2008년 7월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Why the Lingering Hate”. 《ThugLifeArmy.com》. 2005년 1월 5일. 2008년 7월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kaufman, Gil (2005년 9월 15일). “Dr. Dre Attacker Sentenced To One Year In Jail”. 《MTV News》. 2005년 11월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Koerner, Brendan I. (2005년 3월 10일). “The Game Is Up: Why Dr. Dre's protégés always top the charts.”. 《Slate》. 2005년 11월 28일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2008년 5월 24일에 확인함.

- ↑ West, Kanye (2005년 4월 21일). “The Immortals – The Greatest Artists of All Time: 54) Dr. Dre”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2010년 6월 10일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2010년 6월 5일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2006년 11월 8일). “Raekwon Partners With Dr. Dre for Cuban Linx Sequel”. MTV News. 2007년 9월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Jeffries, David (2006년 11월 28일). [(영어) https://www.allmusic.com/album/r935536 “'Buck the World' – Overview”]

|url=값 확인 필요 (도움말). 《AllMusic》. 2008년 5월 26일에 확인함. - ↑ Reid, Shaheem; Rodriguez, Jayson (2007년 8월 30일). “50 Cent Album Preview: Eminem, Dr. Dre Help Curtis 'Keep It Funky'”. 《MTV News》. 2007년 10월 1일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Hoard, Christian (2006년 11월 27일). “Snoop Dogg: Tha Blue Carpet Treatment”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2008년 4월 17일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ J-23 (2006년 11월 7일). “Dr. Dre & Just Blaze Dominate Kingdom Come”. 《HipHopDX.com》. 2009년 1월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2008년 7월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Petridis, Alexis (2007년 3월 30일). “Timbaland, Shock Value”. 《The Guardian》 (London). 2007년 10월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Nima (December 2006). “The D.O.C. Interview (December 2006)”. 《dubcnn.com》. 2013년 1월 31일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kiser, Chad (April 2008). “The D.O.C. Interview (Part 1) (April 2008)”. 《dubcnn.com》. 2013년 1월 31일에 확인함.

- ↑ Moss, Corey (2002년 4월 24일). “N.W.A. May Still Have Attitude, But They Don't Have An Album”. MTV News. 2003년 10월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Crosley, Hillary (2007년 9월 21일). “Dr. Dre: 'Detox' To Be My Last Album”. 《Billboard》. 2007년 9월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Moss, Corey (2002년 4월 3일). “Dr. Dre's Final Album Will Be Hip-Hop Musical”. 《MTV News》. 2008년 4월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Wiederhorn, Jon (2004년 1월 29일). “Dr. Dre's Detox 'The Most Advanced Rap Album Ever,' Co-Producer Says”. MTV News. 2004년 12월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2004년 11월 3일). “Dr. Dre Gets His Groove Back, Revives Plans For Detox LP”. MTV News. 2004년 11월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kaufman, Gil (2008년 2월 29일). “Focus Is Busy With Eminem, Dr. Dre Albums – And A Free One Of His Own”. MTV News. 2008년 3월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Johnson, Dick (2006년 7월 24일). “Scratch Magazine 'Covers' Dr. Dre's 'Detox'”. 《SOHH》. 2007년 6월 21일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 8월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Crosley, Hillary (2007년 1월 5일). “Rotem Rolling with Dr. Dre, 50 Cent”. 《Billboard》. 2007년 9월 29일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Roland – MV-8800 | Production Studio”. Rolandus.com. 2015년 3월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Shake (2006년 11월 1일). “Jay Talks Dre, Detox and Beyonce”. 《HipHopDX》. 2007년 8월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2007년 8월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kreps, Daniel (2008년 6월 26일). “Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg Confirms Dr. Dre's 'Detox' is Finished”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2008년 8월 1일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2008년 12월 5일). “New Eminem Song 'Number One' – Apparently Produced By Dr. Dre – Drops On Mixtape”. MTV News. 2008년 12월 7일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Cohen, Jonathan (2008년 12월 12일). “Exclusive: Eminem Talks New Album, Book”. 《Billboard》. 2008년 12월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Concepcion, Mariel (2009년 5월 29일). “Dr. Dre Debut 'Detox' in Dr. Pepper Ad”. 《Billboard》. 2009년 6월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Interscope Records (2009년 6월 2일). “Dr. Dre and Dr. Pepper”. YouTube. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2009년 5월 28일). “50 Cent, Eminem On Relationship With Dr. Dre: 'We Understand Our Positions'”. MTV News. 2009년 5월 31일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2022년 6월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2008년 12월 16일). “Dr. Dre Raps On Leaked Remix Of Kardinal Offishall's 'Set It Off'”. MTV News. 2009년 7월 20일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Eminem's 'Bottle' breaks download record”. 《Reuters》. 2009년 2월 12일. 2009년 2월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Pietroluongo, Silvio (2009년 2월 11일). “Eminem's 'Bottle' Breaks Digital Record”. 《Billboard》. 2010년 6월 5일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2010년 4월 5일). “Dr. Dre Announces Jay-Z Collabo, 'Under Pressure'”. MTV News. 2010년 4월 9일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ n (2010년 4월 19일). “Scott Storch Produces Dre's 'Under Pressure'”. Rap Basement. 2015년 3월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Reid, Shaheem (2010년 6월 16일). “Dr. Dre's 'Under Pressure,' Featuring Jay-Z, Leaks Online – Music, Celebrity, Artist News”. MTV. 2010년 10월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kuperstein, Slava (2010년 9월 27일). “Dr. Dre Says 'Under Pressure' & Other Leaked 'Detox' Tracks Won't Make Album”. 《HipHopDX》. Cheri Media Group. 2012년 10월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Kush (feat. Snoop Dogg & Akon) – Single by Dr. Dre”. 《iTunes Store》. Apple. January 2010. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ “I Need a Doctor (feat. Eminem & Skylar Grey) – Single by Dr. Dre”. 《iTunes Store》. Apple. February 2011. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ “ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2011 Singles”. Australian Recording Industry Association. 2011년 5월 15일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Mitchell, Gail (2010년 6월 2일). “Dr. Dre To Be Honored By ASCAP”. 《Billboard》. 2010년 6월 5일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Founders Award Dr. Dre”. American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. 2012년 10월 16일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 9월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Barrow, Jerry (2010년 8월 3일). “Dr. Dre Talks The Detox Wait, 'Under Pressure' Frustration And Instrumental Album”. 《Vibe》. 2010년 8월 5일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Eminem And Jay-Z: We're Live From Detroit!”. Rapfix.mtv.com. 2012년 3월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2010년 9월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ Harling, Danielle (2011년 11월 14일). “Dr. Dre Says After 27 Years Of Working On Music He's Taking A Break”. HipHop DX. 2012년 2월 19일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 3월 30일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Coachella 2012: Full lineup revealed; Dr. Dre, Radiohead headline”. 《Los Angeles Times》. 2012년 1월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2021년 12월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ 《Marsha Ambrosius Talks Visual Album, 'Detox,' & Kanye West》. 《YouTube》. 2014년 6월 19일. 2021년 12월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ 《Dawaun Parker Talks Detox》. 《YouTube》. 2014년 9월 17일. 2021년 12월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Vasquez, Andrez (2011년 10월 25일). “Snoop Dogg, DJ Quik, The D.O.C. & Others Team Up For Dr. Dre's 'Detox'”. 《HipHopDX》. Cheri Media Group. 2013년 8월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Muhammad, Latifah (2012년 6월 22일). “7 Reasons Why Dr. Dre's Detox Will Never Drop”. Hip-Hop Wired. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 “3. Dr, Dre Detox – 50 Unreleased Albums We'd Kill To Hear”. 《Complex》. Complex Media. 2012년 8월 8일. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Vasquez, Andrez (2012년 3월 20일). “DJ Quik Does Not Believe Dr. Dre Will Ever Release 'Detox,' Says Dre Is 'Professional' But 'Mean' In Studio”. 《HipHopDX》. Cheri Media Group. 2014년 12월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ Horowitz, Steven J. (2012년 1월 19일). “Game Says Dr. Dre Will 'Never' Release 'Detox'”. 《HipHopDX》. Cheri Media Group. 2013년 3월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 4월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Dr. Dre Announces Final Album, "Compton"”. BallerStatus.com. 2015년 8월 1일.

- ↑ HipHopDX (2015년 8월 1일). “Dr. Dre 'Compton: A Soundtrack By Dr. Dre' Release Date, Cover Art & Tracklist”. 《HipHopDX》.

- ↑ 가 나 “Dr. Dre opens about 'Detox', abuse allegations, & social anxiety in Rolling Stone”. 《Rap-Up》. 2015년 8월 12일. 2015년 8월 15일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2015년 8월 19일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Pallota, Frank (2016년 2월 12일). “Dr. Dre to star in autobiographical series”. 《Money.CNN》. 2016년 2월 12일에 확인함.

- ↑ Benner, Katie (2016년 2월 12일). “Apple and Dr. Dre Are Said to Be Planning an Original TV Show”. 《The New York Times》.

- ↑ Kreps, Daniel (2018년 9월 24일). “Dr. Dre's Apple Music Series 'Vital Signs' Shelved Due to Graphic Content”. 《Rolling Stone》. 2019년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ Winslow, Mike (2016년 10월 5일). “Puff Daddy brings out Dr. Dre on last day of tour”. 《Allhiphop》. 2016년 10월 5일에 확인함.

- ↑ Rowley, Glenn (2021년 12월 8일). “Dr. Dre Set to Release New Music Through 'Grand Theft Auto'”. 《Billboard》. 2021년 12월 8일에 확인함.

- ↑ Schube, Will (2022년 2월 3일). “Listen To Dr. Dre's New EP From 'Grand Theft Auto: The Contract'”. 《UDiscoverMusic》. 2021년 2월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Dr. Dre announces new album with Marsha Ambrosius”. 《HiphopDX》. 2021년 12월 13일. 2021년 12월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Dr. Dre Says He Is Working on Mary J. Blige's New Album”. 《Rap-Up》. 2022년 2월 23일에 확인함.

- ↑ Garvey, Marianne. “Super Bowl LVI Halftime Show set to be a '90s lovefest”. CNN. 2022년 2월 20일에 확인함.