사용자:기록/작업장 2010-2

`31생산지구 - 바니시 - 해적 행위(=해적질) - ?

해적 행위

해적 행위(海賊 行爲, piracy)(=해적질)는 정부와 관게없이 해상에서 강도·약탈을 하기위해 사적으로 모인 범죄 집단의 습격·행위이다.

이는 해상 뿐만 아니라, 주요한 수역(水域)에서의 범죄 행위를 포함한다. 그러나 함께 승선한 사람간의 범죄 행위는 포함하지 않는다.(예를 들어, 같은 배에 탄 한 승객이 다른 승객으로 부터 훔치는 행위).

국가와 관계없는 무리의 해안을 습격·약탈 행위를 '해적 행위'라 일컫는데, 19세기까지 국가의 허가아래 상선을 나포하던 사나포선(私拿捕船,privateer)의 습격·나포 행위와는 구별되어야 할 것이다.

! 이미지 사용불가:Public domain in the US.

정의

1982 체결된 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)에 따르면 '해적 행위'란 사적으로인 다른 배나 항공기의 승객에 대한 구금·강간·약탈등의 범죄 행위를 말한다. 또 해적 행위는 국가의 사법권에서 벗어나 배,항공기,사람, 또는 야외의 공공 재산에 대한 범죄행위를 포함한다. 사실 해적 행위는 국가 사법권이 개입해야될 부분이다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 오늘 날의 국제 사회는 이같은 해적행위가 초래하는 문제에 직면해있다.[1]

어원

영어의 "pirate"는 라틴어의 pirata에 기원을 두는데, pirata는 그리스어 πειρατής (peiratēs) "약탈자"[2]from πειράομαι (peiráomai) "시도하다", from πεῖρα (peîra) "시도하다 경험하다".[3] 가 어원이다. 또한 peril과 어원이 같다.[4]

역사

고대의 기원

바다를 통한 교역만큼이나 해적의 역사도 오래되었다고 보아야 한다. 일찍히 문헌상으로 이미 기원전 13세기 에게해와 지중해를 위협하던 해적들에 대한 기록이 있다.[5] 고전고대에 그리스인은 물론이고 로마인에게까지 Illyrians와 Tyrrhenians는 해적으로 이름났다. Lemnos섬은 그리스 세력에 저항하며 트라키아 해적의 소굴로 살아남았다. 페니키아인들은 그들의 때때로 해적질에 기대어 항해를 하기도 하였고, 어린아이들을 붙잡아 노예로 팔기도 하였다.[6]

기원전 3세기, 해적들의 공격은 아나톨리아의 올림포스를 빈곤에 빠지게 하였다. 일찍히 고대 해적 중에 이름난 Illyians는 발칸반도 서쪽에 살았다. 끊임없이 아드리아해를 공격하며 Illyrians는 로마와 충돌을 빚게 된다. 이는 기원전 168년, 그들의 위협끝에 로마가 Illyria를 정복하여 속주로 삼을때까지 계속되었다.

기원전 1세기 동안, 아나톨리아 해변을 낀 해적국가가 있었는데, 동지중해 로마 제국의 교역을 위협했다. 기원전 75년 한 에게해 항해 때[7], 줄리어스 시저는 Cilician 해적에 의해 납치된다. 그리고 Dodecanese의 Pharmacusa에 억류되게 된다.[8] 포로로 붙잡혀 있는 동안 그는 몸가짐을 유지하였고, 도처로 응원을 받았다. 해적들이 몸값으로 20 talents of gold를 요구하기로 마음먹었을때, 시저는 그의 몸값이 최소한 50 talents of gold는 된다고 주장했고, 해적들은 정말로 50 talants로 몸값을 올렸다. 나중에 몸값이 지불되어 풀려난 시저는 함대를 이끌고 해적들을 모조리 사로잡아 사형에 처했다.

원로원은 마침내 기원전 67년, 해적을 처리하기 위해 힘쓰기로 하였고(Lex Gabinia), 폼페이우스는 3개월간 해전을 치러 해적들의 위협을 진압하였다.

서기 258년 초기, Gothic-Herulic 선단이 흑해와 마르마라해의 해변 도시를 파괴하였다. 에게해의 해변은 몇년 후 비슷한 공격을 받는다. 264년, Goths(고트) Galatia와 Cappadocia(카파도키아)까지 영향권에 두었고, 고트 해적은 키프로스와 크레타섬에 이르렀다. 그 과정에서 고트족은 막대한 노획물과 수천의 포로를 얻었다.

286년, a Roman military commander of Gaulish origins, Carausius는 Classis Britannica 함대에, Armorica 해변과 Belgic Gaul을 습격하는 프랑크족과 색슨족 해적을 섬멸하도록 명했다.

로마의 브리타니아 주에서, 성 패트릭이 아일랜드 해적에 붙잡혀 노예가 되기도 하였다.

일찌기 폴리네시아 전사들은 해변과, 강기슭의 마을을 공격하였다. 그들은 바다를 그들의 치고빠지기 전술을 쓰며 그들이 반격당할때 퇴각할 수 있는 안전지대로 삼았다.

지금까지 가장 널리 알려진 해적은 중세시대 초기, 스칸디나비아 일대에서 전사이자 약탈자로, 786년에서 1066년 사이 '바이킹 시대'를 열었던 '바이킹'이다. 그들은 서부 유럽 전역의 해변과 강가의 도시를 공격하였고, Seville는 844년 Norse에 습격당하기도 했다. 바이킹은 심지어 북부 아프리카와 이탈리아까지도 공격하였다. 그들은 또한 발트해 연안 일대, 강을 타고 동유럽의 흑해 그리고 페르시아까지 약탈하였다. 중앙집권화를 이루지 못한 유럽 대륙 전체가 해적들의 약탈 대상이 되었다.

한편, 이슬람 해적은 지중해를 넘나들었다. 9세기 말, 이슬람 해적은 남부 프랑스와 북부 이탈리아 일대에서 활동하였다.[9] 846년 이슬람 약탈자들은 로마를 약탈하고 바티칸을 파괴했다. 911년, Narbonne의 주교는 프랑스로 되돌아갈 수가없었다. Fraxinet의 이슬람교도가 모든 알프스의 길을 지배하고 있었기 때문이다. 10세기에 이슬람 해적들은 Balearic섬 밖으로 이동하였다. 824년에서 961년 사이, 크레타의 아랍 해적은 지중해 전역을 습격 대상으로 하였다. 14세기, 이슬람 해적세력의 습격으로 베네치아인인 크레타 군주는 베니스에 지속적인 함대 경계를 청하였다.[10]

5~6세기의 발칸반도의 슬라브 침략 이후, 슬라브 부족은 7세기 전반 Pagania와 Dalmatia 사이와 Zachlumia에 정착하였다. 이 슬라브인들은 고대 Illyrian의 해적질을 재개하였고, 종종 아드리아해를 습격했다. 642년 그들은 남부 이탈리아를 쳐들어가 Benevento의 Siponte를 습격했다. 그들의 아드리아 해역 습격은 빠르게 늘어, 전체 해역은 더이상 안전한여행이 불가능 했다.

827~82년 사이 베네치아 해군이 시칠리아 인근으로 나가서 활동하는 사이에 Narentines 이라 불린 그들은 그들의 습격대상을 찾는데 자유로웠다. 곧 베네치아 함대는 아드리아 해로 돌아왔고, Narentines는 일시 그들의 관습을 버렸다, 베니스에서 조약을 체결하고, 그들의 슬라브 이교도 지도자는 기독교 세례를 받았다. 834~835년, 그들은 협정을 깼고, Neretva 해적은 Benevento에서 돌아가는 베네치아 상인을 습격했다. 그리고 베니스 전군은 839~840년 그들을 토벌하려 했으나 완전히 실패했다. 나중에 그들이 종종 아랍 해적과 함께 베네치아를 습격하곤 했다. 846년 Narentines 베니스를 자체를 파괴하고, Caorle의 산호도시를 약탈했다. 870년 3월 중순 그들은 콘스탄티노플의 교회 평의회에서 돌아오던 로마 주교의 사자를 납치했다. 이 사건은 비잔틴 군대를 움직이게 했고, 그들에게 기독교를 전파했다.

나중에 아랍 약탈자들이 아라비아해 연안을 약탈했다. c. 872년 그리고 황제의 해군에 밀려 퇴각하였고, Narentines는 여전히 베네치아 연해에서 습격을 계속했다.이는 887년에서 888년 이탈리아인들과 충돌 원인이 되었다. 베네치아인들의 헛된 저항은 10세기에서 11세기동안 계속 되었다.

937년, 아일랜드 해적은 스코틀랜드인과, 바이킹, 픽트인, 웨일스인과 함께 영국에서의 침략을 함께했다. Athelstan이 그들을 처리했다.

1168년, Arkona의 Rani 성채를 덴마크인이 정복하면서 발트해의 슬라브 해적질은 끝났다. 12세기 서부 스칸디나비아 연안은, 발트 동부 해안에서 온 Curonians과 Oeselians에 의해 약탈당했다. 13세기와 14세기, 해적들은 한자 루트를 위협하여, 해상 교역의 단절을 초래했다. Gotland의 Victual Brothers는 사략선의 동료였는데 나중에 해적질로 전향한다. 약 1440년까지, 북해와 발트해의 해상교역은 해적들로 공격으로 진정으로 위험하였다.

H. Thomas Milhorn 이 말하길, 영국인 William Maurice는 1241년 해적 행위로 유죄를 선고받고, 처음으로 hanged, drawn and quartered[11] 형에 처한 인물이다. 이는 당시 왕인 헨라 3세가 특별히 이같은 범죄행위에 대한 엄중한 본보기로 삼은 것이다.

초기 비잔틴, Maniot - 거친 그리스 인중 하나 - 는 해적으로 알려졌다. Maniots는 척박한 자신들의 땅과 적은 소득을 이유로, 해적질이 정당하다고 여겼다. Maniot 해적의 주요한 희생자는 터키인들로이었으나, Maniots는 전유럽 국가를 역시 표적으로 삼았다.

Haida 그리고 Tlingit 부족은 남부 알래스카 해안과 북서부 브리티시 콜롬비아에 살았는데, 전통적으로 용맹한 전사, 해적과 그리고 노예상인으로 알려졌다. 이들은 멀리 캘리포니아까지도 습격했다.[12]

On the Indian coast

Instances of Piracy in India are recorded on Vedas. However the most interesting one is when the issue of piracy was utilized as a excuse for war. Invasion of Sindh, In the seventh century the new kingdom of Hajjaz wanted to expand Arab domination over India especially Sindh.The Arab Caliph of Baghdad was in search of an excuse to invade India. The excuse taken was that a ship enroute from Sri Lanka to Baghdad was carrying among valuables some slave girls was looted off Debal. The Caliph demanded compensation and the King Dahir of Sindh rightfully denied as the pirates were not in his control. This became an excuse for war between Arabs and Sindh.[13] Since the 14th century the Deccan (Southern Peninsular region of India) was divided into two entities: on the one side stood the Muslim-ruled Bahmani Sultanate, and on the other stood the Hindu kings rallied around the Vijayanagara Empire. Continuous wars demanded frequent resupplies of fresh horses, which were imported through sea routes from Persia and Africa. This trade was subjected to frequent raids by thriving bands of pirates based in the coastal cities of Western India. One of such was Timoji, who operated off Anjadip Island both as a privateer (by seizing horse traders, that he rendered to the raja of Honavar) and as a pirate who attacked the Kerala merchant fleets that traded pepper with Gujarat.

During the 16th and 17th centuries there was frequent European piracy against Mughal Indian vessels, especially those en route to Mecca for Hajj. The situation came to a head, when Portuguese attacked and captured the vessel Rahimi which belonged to Mariam Zamani the Mughal queen, which led to the Mughal seizure of the Portuguese town Daman.[14] In the 18th century, the famous Maratha privateer Kanhoji Angre ruled the seas between Mumbai and Goa.[15] The Marathas attacked British shipping and insisted that East India Company ships pay taxes if sailing through their waters.[16]

At one stage, the pirate population of Madagascar numbered close to 1000.[17] Île Sainte-Marie became a popular base for pirates throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. The most famous pirate utopia is that of Captain Misson and his pirate crew, who allegedly founded the free colony of Libertatia in northern Madagascar in the late 17th century. In 1694, it was destroyed in a surprise attack by the island natives.[18]

The southern coast of the Persian Gulf became known as the Pirate Coast as raiders based there harassed foreign shipping. Early British expeditions to protect the Indian Ocean trade from raiders at Ras al-Khaimah led to campaigns against that headquarters and other harbors along the coast in 1819.[19]

동아시아의 해적

동아시아의 해적, 왜구 왜구는 일본을 거점으로 동아시아를 활동무대로 삼아 13세기부터 300년 가까이 해적질을 지속했다.

동남아시아의 해적은 원나라의 함대가 자바동맹의 배신으로 퇴각하면서 시작되었다. 그들은 강화된 돛 구조를 가진 정크선을 선호하였다. Marooned navy officers는 대개 광둥인이나 Hokkien부족이었는데, 그들 무리는 주로 강어귀에 자리했는데, 대부분 그들 자신을 보호하기 위해서였다. 그들은 lang으로 알려진 현지의 보병을 모아 그들의 요새를 구축했다. 그들은 권투와, 해병과 같은 항해능력, 거의 Sumatran과 자바섬 강어귀에서 살아남았다. 그들의 강력함과 광포함은 비단과 향신료를 나르는 무역의 발전과 함께했다.

그러나, 대부분의 힘있는 동아시아의 해적함대는 청나라 중기에 존재했다. 해적함대는 19세기 초까지 계속해서 성장했다. 대규모의 해적 선단은 중국 경제에 큰 영향을 끼쳤다. 그들은 중국의 정크 무역선을 먹잇감으로 삼아 Fujian과 광둥 그리고 중요한 교역로에서 번창하였다. Pirate fleets exercised hegemony over villages on the coast, collecting revenue by exacting tribute and running extortion rackets. In 1802, the menacing Zheng Yi inherited the fleet of his cousin, captain Zheng Qi, whose death provided Zheng Yi with considerably more influence in the world of piracy. Zheng Yi와 그의 아내 Zheng Yi Sao (who would eventually inherit the leadership of his pirate confederacy)는 1804년, 천여명으로 구성된 해적 연합을 구성하였다. 그들은 충분히 청나라 해군과 맞설 수 있을 힘을 갖추었다. 그러나 기근과 청 해군의 개입, 그리고 내부의 균열은 1820년대 중국의 해적의 붕괴를 초래하였.그리고 이전과 같은 상태로 되돌아 가지 못했다.

남부 Sulawesi의 Buginese 항해사들은, 멀리 싱가포르 서부, 필리핀 북부 까지 해적질의 대상으로 삼아 해적만큼이나 악명을 떨쳤다.[20] Orang laut 해적은 말라카해협과 싱가포르 해역[21]을 영향권에 두었고, Malay 그리고 Sea Dayak 해적들은 보르네오섬을 근거지로 싱가포르와 홍콩 사이 해역을 오가는 무역선을 먹이로 삼았다.[22]

In Eastern Europe

One example of a pirate republic in Europe from the 16th through the 18th century was Zaporizhian Sich. Situated in the remote Steppe, it was populated with Ukrainian peasants that had run away from their feudal masters, outlaws of every sort, destitute gentry, run-away slaves from Turkish galleys, etc. The remoteness of the place and the rapids at the Dnepr river effectively guarded the place from invasions of vengeful powers. The main target of the inhabitants of Zaporizhian Sich who called themselves "Cossacks" were rich settlements at the Black Sea shores of Ottoman Empire and Crimean Khanate.[23] By 1615 and 1625, Zaporozhian Cossacks had even managed to raze townships on the outskirts of Istanbul, forcing the Ottoman Sultan to flee his palace.[24] Don Cossacks under Stenka Razin even ravaged the Persian coasts.[25]

In North Africa

The Barbary pirates were pirates and privateers that operated from North African (the "Barbary coast") ports of Tunis, Tripoli, Algiers, Salé and ports in Morocco, preying on shipping in the western Mediterranean Sea from the time of the Crusades as well as on ships on their way to Asia around Africa until the early 19th century. The coastal villages and towns of Italy, Spain and Mediterranean islands were frequently attacked by them and long stretches of the Italian and Spanish coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants; after 1600 Barbary pirates occasionally entered the Atlantic and struck as far north as Iceland. According to Robert Davis[26][27] between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa and Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 19th centuries. The most famous corsairs were the Ottoman Hayreddin and his older brother Oruç Reis (Redbeard), Turgut Reis (known as Dragut in the West), Kurtoğlu (known as Curtogoli in the West), Kemal Reis, Salih Reis and Koca Murat Reis. A few Barbary pirates, such as Jan Janszoon and John Ward [Yusuf Reis], were renegade English privateers who had converted to Islam.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the United States treated captured Barbary corsairs as prisoners of war, indicating that they were considered as legitimate privateers by at least some of their opponents, as well as by their home countries.

In the Caribbean

In 1523, Jean Fleury seized two Spanish treasure ships carrying Aztec treasures from Mexico to Spain.[28] The great or classic era of piracy in the Caribbean extends from around 1560 up until the mid 1720s. The period during which pirates were most successful was from 1700 until the 1730s. Many pirates came to the Caribbean after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession. Many people stayed in the Caribbean and became pirates shortly after that. Others, the buccaneers, arrived in the mid-to-late 17th century and made attempts at earning a living by farming and hunting on Hispaniola and nearby islands; pressed by Spanish raids and possibly failure of their means of making a living, they turned to a more lucrative occupation (not to mention more active and conducive to revenge). Caribbean piracy arose out of, and mirrored on a smaller scale, the conflicts over trade and colonization among the rival European powers of the time, including the empires of Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal and France. Most of these pirates were of English, Dutch and French origin. Because Spain controlled most of the Caribbean, many of the attacked cities and ships belonged to the Spanish Empire and along the East coast of America and the West coast of Africa. Dutch ships captured about 500 Spanish and Portuguese ships between 1623 and 1638.[5] Some of the best-known pirate bases were New Providence, in the Bahamas from 1715 to 1725,[29] Tortuga established in the 1640s and Port Royal after 1655. Among the most famous Caribbean pirates are Edward Teach or "Blackbeard", Calico Jack Rackham and Henry Morgan.

In 1827, Britain declared that participation in the slave trade was piracy, a crime punishable by death. The power of the Royal Navy was subsequently used to suppress the slave trade, and while some illegal trade, mostly with Brazil and Cuba, continued, the Atlantic slave trade would be eradicated by the middle of the 19th century.[30]

Popular Image

In the popular modern imagination, pirates of the classical period were rebellious, clever teams who operated outside the restricting bureaucracy of modern life. Pirates were also depicted as always raising their Jolly Roger flag when preparing to hijack a vessel. The Jolly Roger is the traditional name for the flags of European and American pirates and a symbol for piracy that has been adopted by film-makers and toy manufacturers.

Pirate democracy

Unlike traditional Western societies of the time, many pirate crews operated as limited democracies. Pirate communities were some of the first to instate a system of checks and balances similar to the one used by the present-day United States and many other countries. The first record of such a government aboard a pirate sloop dates to the 1600s.[31]

Both the captain and the quartermaster were elected by the crew; they, in turn, appointed the other ship's officers. The captain of a pirate ship was often a fierce fighter in whom the men could place their trust, rather than a more traditional authority figure sanctioned by an elite. However, when not in battle, the quartermaster usually had the real authority. Many groups of pirates shared in whatever they seized; pirates injured in battle might be afforded special compensation similar to medical or disability insurance.

There are contemporary records that many pirates placed a portion of any captured money into a central fund that was used to compensate the injuries sustained by the crew. Lists show standardised payments of 600 pieces of eight ($156,000 in modern currency) for the loss of a leg down to 100 pieces ($26,800) for loss of an eye. Often all of these terms were agreed upon and written down by the pirates, but these articles could also be used as incriminating proof that they were outlaws.

Pirates readily accepted outcasts from traditional societies, perhaps easily recognizing kindred spirits, and they were known to welcome them into the pirate fold. For example as many as 40% of the pirate vessels' crews were slaves liberated from captured slavers. Such practices within a pirate crew were tenuous, however, and did little to mitigate the brutality of the pirate's way of life.

Treasure

Even though pirates raided many ships, few, if any, buried their treasure. Often, the "treasure" that was stolen was food, water, alcohol, weapons, or clothing. Other things they stole were household items like bits of soap and gear like rope and anchors, or sometimes they would keep the ship they captured (either to sell off or because it was better than their ship). Such items were likely to be needed immediately, rather than saved for future trade. For this reason, there was no reason for the pirates to bury these goods. Pirates tended to kill few people aboard the ships they captured; oftentimes they would kill no one if the ship surrendered, because if it became known that pirates took no prisoners, their victims would fight to the last and make victory both very difficult and costly in lives. Contrariwise, ships would quickly surrender if they knew they would be spared. In one well-documented case 300 heavily armed soldiers on a ship attacked by Thomas Tew surrendered after a brief battle with none of Tew's 40-man crew being injured.[32]

Rewards

Pirates had a system of hierarchy on board their ships determining how captured money was distributed. However, pirates were more "egalitarian" than any other area of employment at the time. In fact pirate quartermasters were a counterbalance to the captain and had the power to veto his orders. The majority of plunder was in the form of cargo and ship's equipment with medicines the most highly prized. A vessel's doctor's chest would be worth anywhere from £300 to £400, or around $470,000 in today's values. Jewels were common plunder but not popular as they were hard to sell, and pirates, unlike the public of today, had little concept of their value. There is one case recorded where a pirate was given a large diamond worth a great deal more than the value of the handful of small diamonds given his crewmates as a share. He felt cheated and had it broken up to match what they received.[33]

Spanish pieces of eight minted in Mexico or Seville were the standard trade currency in the American colonies. However, every colony still used the monetary units of pounds, shillings and pence for bookkeeping while Spanish, German, French and Portuguese money were all standard mediums of exchange as British law prohibited the export of British silver coinage. Until the exchange rates were standardised in the late 1700s each colony legislated its own different exchange rates. In England, 1 piece of eight was worth 4s 3d while it was worth 8s in New York, 7s 6d in Pennsylvania and 6s 8d in Virginia. One 18th century English shilling was worth around $58 in modern currency so a piece of eight could be worth anywhere from $246 to $465. As such, the value of pirate plunder could vary considerably depending on who recorded it and where.[34][35]

Ordinary seamen received a part of the plunder at the captain's discretion but usually a single share. On average, a pirate could expect the equivalent of a year's wages as his share from each ship captured while the crew of the most successful pirates would often each receive a share valued at around £1,000 ($1.17 million) at least once in their career.[33] One of the larger amounts taken from a single ship was that by captain Thomas Tew from an Indian merchantman in 1692. Each ordinary seaman on his ship received a share worth £3,000 ($3.5 million) with officers receiving proportionally larger amounts as per the agreed shares with Tew himself receiving 2½ shares. It is known there were actions with multiple ships captured where a single share was worth almost double this.[33][36]

By contrast, an ordinary seamen in the Royal Navy received 19s per month to be paid in a lump sum at the end of a tour of duty which was around half the rate paid in the Merchant Navy. However, corrupt officers would often "tax" their crews' wage to supplement their own and the Royal Navy of the day was infamous for its reluctance to pay. From this wage, 6d per month was deducted for the maintenance of Greenwich Hospital with similar amounts deducted for the Chatham Chest, the chaplain and surgeon. Six months' pay was withheld to discourage desertion. That this was insufficient incentive is revealed in a report on proposed changes to the RN Admiral Nelson wrote in 1803; he noted that since 1793 more than 42,000 sailors had deserted. Roughly half of all RN crews were pressganged and these not only received lower wages than volunteers but were shackled while the vessel was docked and were never permitted to go ashore until released from service.[37][38]

Although the Royal Navy suffered from many morale issues, it answered the question of prize money via the 'Cruizers and Convoys' Act of 1708 which handed over the share previously gained by the Crown to the captors of the ship. Technically it was still possible for the Crown to get the money or a portion of it but this rarely happened. The process of condemnation of a captured vessel and its cargo and men was given to the High Court of the Admiralty and this was the process which remained in force with minor changes throughout the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

The share-out of prize-money is given below in its pre-1808 state.

(a) 1/8 Flag Officer (b) 2/8 Captain(s) (c) 1/8 Captains of Marines, Lieutenants, Masters, Surgeons (d) 1/8 Lieutenants of Marines, Secretary to Flag Officer, Principal Warrant Officers, Chaplains. (e) 1/8 Midshipmen, Inferior Warrant Officers, Principal Warrant Officer's Mates, Marine Sergeants (f) 2/8 The Rest.

After 1808 the regulations were changed to give the following:

(a) 1/3 of the Captain's share (b) 2/8 (c) 1/8 (d) 1/8 (e) & (f) 4/8

Even the flag officer's share was not quite straightforward; he would only get the full one-eighth if he had no junior flag officer beneath him. If this was the case then he would get a third share. If he had more than one then he would take one half while the rest was shared out equally.

There was a great deal of money to be made in this way. The record breaker, admittedly before our wars, was the capture of the Spanish frigate the Hermione, which was carrying treasure in 1762. The value of this was so great that each individual seaman netted £485 ($1.4 million in 2008 dollars).[39] The two captains responsible, Evans and Pownall, got just on £65,000 each ($188.4 million). In January 1807 the frigate Caroline took the Spanish San Rafael which brought in £52,000 for her captain, Peter Rainier (who had been only a Midshipman some thirteen months before). All through the wars there are examples of this kind of luck falling on captains. Another famous 'capture' was that of the Spanish frigates Thetis and Santa Brigada which were loaded with specie. They were taken by four British frigates who shared the money, each captain receiving £40,730. Each lieutenant got £5,091, the Warrant Officer group, £2,468, the midshipmen £791 and the individual seamen £182.

It should also be noted that it was usually only the frigates which took prizes; the ships of the line were far too ponderous to be able to chase and capture the smaller ships which generally carried treasure. Nelson always bemoaned that he had done badly out of prize money and even as a flag officer received little. This was not that he had a bad command of captains but rather that British mastery of the seas was so complete that few enemy ships dared to sail.[1]

Comparison chart using the share distribution known for three pirates against the shares for a Privateer and wages as paid by the Royal Navy.

| Rank | Bartholomew Roberts | George Lowther | William Phillips | Privateer (Sir William Monson) |

Royal Navy Per Month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Captain | 2 shares | 2 shares | 1½ shares | 10 shares | £8, 8s |

| Master | 1½ shares | 1½ shares | 1¼ shares | 7 or 8 shares | £4 |

| Boatswain | 1½ shares | 1¼ shares | 1¼ shares | 5 shares | £2 |

| Gunner | 1½ shares | 1¼ shares | 1¼ shares | 5 shares | £2 |

| Quartermaster | 2 shares | 4 shares | £1, 6s | ||

| Carpenter | 1¼ shares | 5 shares | £2 | ||

| Mate | 1¼ shares | 5 shares | £2, 2s | ||

| Doctor | 1¼ shares | 5 shares | £5 +2d per man aboard | ||

| "Other Officers" | 1¼ shares | various rates | various rates | ||

| Able Seamen (2 yrs experience) Ordinary Seamen (some exp) Landsmen (pressganged) |

1 share |

1 share |

1 share |

22s 19s 11s |

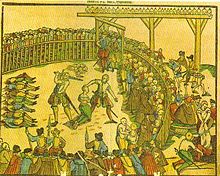

Punishment

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, once pirates were caught, justice was meted out in a summary fashion, and many ended their lives by "dancing the hempen jig", or hanging at the end of a rope. Public execution was a form of entertainment at the time, and people came out to watch them as they would to a sporting event today. Newspapers were glad to report every detail, such as recording the condemned men's last words, the prayers said by the priests for their immortal souls, and their final agonising moments on the gallows. In England most of these executions took place at Execution Dock on the River Thames in London.

In the cases of more famous prisoners, usually captains their punishments extended beyond death. Their bodies were enclosed in iron cages (for which they were measured before their execution) and left to swing in the air until the flesh rotted off them- a process that could take as long as two years. The bodies of captains such as William Kidd, Charles Vane, William Fly, and Jack Rackham were all treated this way.[40]

사나포선(私拿捕船, Privateer)

A privateer or corsair used similar methods to a pirate, but acted while in possession of a commission or letter of marque from a government or monarch authorizing the capture of merchant ships belonging to an enemy nation. For example, the United States Constitution of 1787 specifically authorized Congress to issue letters of marque and reprisal. The letter of marque was recognized by international convention and meant that a privateer could not technically be charged with piracy while attacking the targets named in his commission. This nicety of law did not always save the individuals concerned, however, as whether one was considered a pirate or a legally operating privateer often depended on whose custody the individual found himself in—that of the country that had issued the commission, or that of the object of attack. Spanish authorities were known to execute foreign privateers with their letters of marque hung around their necks to emphasize Spain's rejection of such defenses. Furthermore, many privateers exceeded the bounds of their letters of marque by attacking nations with which their sovereign was at peace (Thomas Tew and William Kidd are notable examples), and thus made themselves liable to conviction for piracy. However, a letter of marque did provide some cover for such pirates, as plunder seized from neutral or friendly shipping could be passed off later as taken from enemy merchants.

The famous Barbary Corsairs (authorized by theOttoman Empire) of the Mediterranean were privateers, as were the Maltese Corsairs, who were authorized by the Knights of St. John, and the Dunkirkers in the service of the Spanish Empire. From 1609 to 1616, England lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates.[41] One famous privateer was Sir Francis Drake. His patron was Queen Elizabeth I, and their relationship ultimately proved to be quite profitable for England.[42]

Privateers were a large proportion of the total military force at sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. During the Nine Years War, the French adopted a policy of strongly encouraging privateers, including the famous Jean Bart, to attack English and Dutch shipping. England lost roughly 4,000 merchant ships during the war.[43] In the following War of Spanish Succession, privateer attacks continued, Britain losing 3,250 merchant ships.[44] During the War of Austrian Succession, Britain lost 3,238 merchant ships and France lost 3,434 merchant ships to the British.[43]

During King George's War, approximately 36,000 Americans served aboard privateers at one time or another.[43] During the American Revolution, about 55,000 American seamen served aboard the privateers.[45] The American privateers had almost 1,700 ships, and they captured 2,283 enemy ships.[46] Between the end of the Revolutionary War and 1812, less than 30 years, Britain, France, Naples, the Barbary States, Spain, and the Netherlands seized approximately 2,500 American ships.[47] Payments in ransom and tribute to the Barbary states amounted to 20% of United States government annual revenues in 1800.[48] Throughout the American Civil War, Confederate privateers successfully harassed Union merchant ships.[49]

Privateering lost international sanction under the Declaration of Paris in 1856.

Modern age

개요

수송용 선박에 대한 해적행위 보고(전 세계적으로 130~160억 달러가량 피해)[50][51]에 따르면 특히 홍해와 인도양 사이, 소말리아 연안, 그리고 말라카해협과 싱가포르 사이의 바닷길을 연간 약 5만 척의 상선이 이용한다.

최근[52], 소말리아 연안의 해적행위가 늘면서, 미국을 주축으로 한 연합 함대는 순찰을 강화하게 되었다. 현대 해적은 소형 보트를 이용함으로써 소수의 승무원이 타고있는 화물선으로 부터 이익을 취한다.그들은 또한 대형선박을 이용해 소형 공격선에 보급을 한다. 배를 이용한 큰 규모의 국제상거래로, 이를 대상으로한 현대 해적의 해적 행위는 성공적이다. 아덴의 걸프만이나 말라카 해협과 같은 주요해로의 경우 좁은 수역이 모터보트를 이용한 해적 행위를 용이하게 한다.[53][54] 다른 활동 영역인 남중국해나 니제르 삼각주 역시 그렇다.많은 선박들이 왕래를 위해 낮은 속도로 항해하는데, 이 점이 해적들의 표적이 되게 한다. 또한 해적들은 종종 개발도상국의 작은 해군과 함께 움직인다. 해적들은 돛단배를 이용해 단속으로 부터 피하기도 한다.냉전시기 해군이 줄어들고, 그에 따라 순찰도 줄었다. 반면 무역은 늘어났는데, 이는 많은 해적이 조직되게 하는 원인이 되었다. 현대 해적은 가끔 신디케이트를 구성하기도 하지만 대개는 소규모 집단이다.

International Maritime Bureau(IMB)는 주장하는 통계치를 보면 해적행위는 1995년으로 돌아가고 있다. 이는 승무원들에 대한 납치가 압도적이라는 것이다. 예를 들어 2006년, 239회의 공격에, 77명의 승무원이 납치·억류 되었으며, 188명의 인질이 되었다. 그러나 오직 15명만이 살해 당했다.[55] 2007년에는 263회로 10%가량 공격 횟수가 줄었다. 하지만 총포를 이용한 해적들의 공격은 35% 늘었다. 이에따라 승무원들의 부상은 64명으로 2006년의 17명과 비교된다.[56]이 숫자는 부상당하지 않은 인질을 제외한다.

2009년 9개월간 아덴의 걸프만·소말리아 해안에서의 해적 행위 횟수는 이미 작년 동기를 넘어섰다.1월 부터 9월 까지 공격횟수는 293회에서 306회로 늘었다. 2009년 현재까지 114회의 해적 접근의 경우 중 34회 납치되었다.총포를 이용한 해적 행위는 176회로 지난해의 76회를 넘어섰다.[57]

현대 해적은 어떤 경우 짐이 아닌, 승무원 개인의 소지품이나, 임금·항구정박 수수료 지불을 위한 현금 등에 더 관심을 갖기도 한다.어떤 경우에는 배에서 선원을 떼어놓고, 새로 도장을 하여 부패한 공무원으로 부터 선박증명서를 손에 넣어 선박 기록을 세탁하기도 한다.[58] 현대 해적은 또한 정치적으로 불안한 곳에 자리한다. 예를 들어 베트남에서 미국의 철수 이후, 타이 해적은 보트로 탈출하려는 많은 베트남인을 겨냥 했다. 게다가 소말리아같이 정부기능이 붕괴된 경우, 지방 군벌이 UN식량계획의 구호물자 선박을 공격하기도 했다.[59]

Sea Shepherd 같은 환경 단체들은 두가지 사례(일본 포경선에 불법적으로 충각으로 사용하고, butyric acid를 갑판에 뿌림)에 대하여 해적 행위와 테터리즘에 관련한 비난 받는다. 비록 Sea Shepherd 선박이 치명적인 무기를 사용한 것은 아니지만, 일부는 그들의 전략과 방식이 해적 행위와 같다며 비난한다.[60][61]

2005년 11월 소말리아 앞바다에서 있었던 U.S 크루즈선박 Seabourn Spirit에 대한 공격은, 정교한 해적공격의 한 예이다. 해적들은 거의 100마일(160km)밖에서 모함으로부터 고속정을 내보냈다. 아울러 해적들은 자동화 화기와 Rocket-propelled grenade(RPG)로 무장했다.[62]

많은 국가들이 가능한 해적행위를 막기위하여, 배나 승무원이 무장하였을 경우 그들의 영해에 진입하거나 항구에 입항을 금한다.[63] 또한 해운 선사들은 때때로 무장한 경비요원을 고용한다.

현대적인 해적의 정의는 아래를 포함한다.

- 탑승 행위 Boarding

- 강탈 Extortion

- 인질 Hostage taking

- 보상금을 목적으로 한 납치 Kidnapping of people for ransom

- 살해 Murder

- 강도 Robbery

- 배가 침몰시킬 수 있는 파괴행위 Sabotage resulting in the ship subsequently sinking

- 배의 물품 장악 Seizure of items or the ship

- 의도적 난파 Shipwrecking done intentionally to a ship

현대 해적은 또한 첨단 과학기술을 사용한다. 다음은 보고된 해적 행위에 포함되는 것이다. 휴대폰, 위성전화, GPS, 음파탐지기, 현대식 모터보트, 마체테(칼), 전투용 소검, 저격용 라이플, 산탄총, 권총, 고정 기관총, 심지어 RPG나 유탄 발사기 까지.

Recent incidents

- During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, two coaster ships were hijacked and sunk by the IRA in the span of one year, between February 1981 and February 1982.

- A collision between the container ship Ocean Blessing and the hijacked tanker Nagasaki Spirit occurred in the Malacca Straits at about 23:20 on 19 September 1992. Pirates had boarded the Nagasaki Spirit, removed its captain from command, set the ship on autopilot and left with the ship's master for a ransom. The ship was left going at full speed with no one at the wheel. The collision and resulting fire took the lives of all the sailors of Ocean Blessing; from Nagasaki Spirit there were only 2 survivors. The fire on the Nagasaki Spirit lasted for six days; the fire aboard the Ocean Blessing burned for six weeks.[64]

- The cargo ship Chang Song boarded and taken over by pirates posing as customs officials in the South China Sea in 1998. Entire crew of 23 was killed and their bodies thrown overboard. Six bodies were eventually recovered in fishing nets. A crackdown by the Chinese government resulted in the arrest of 38 pirates and the group's leader, a corrupt customs official, and 11 other pirates who were then executed.[65]

- The New Zealand environmentalist, yachtsman and public figure Sir Peter Blake was killed by Brazilian pirates in 2001.[66]

- Pirates boarded the supertanker Dewi Madrim in March 2003 in the Malacca Strait. Articles like those written by the Economist indicate the pirates did not focus on robbing the crew or cargo, but instead focused on learning how to steer the ship and stole only manuals and technical information. However, the original incident report submitted to the IMO by the IMB would indicate these articles are incorrect and misleading. See also: Letter to the Editor of Foreign Affairs.

- The American luxury liner The Seabourn Spirit was attacked by pirates in November 2005 off the Somalian coast. There was one injury to a crewmember; he was hit by shrapnel.

- Pirates boarded the Danish bulk carrier Danica White in June 2007 near the coast of Somalia. USS Carter Hall tried to rescue the crew by firing several warning shots but wasn't able to follow the ship into Somali waters.[2]

- In April 2008 pirates seized control of the French luxury yacht Le Ponant carrying 30 crew members off the coast of Somalia.[67] The captives were released on payment of a ransom. The French military later captured some of the pirates, with the support of the provisional Somali government.[68] On June 2, 2008, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution enabling the patrolling of Somali waters following this and other incidents. The Security Council resolution provided permission for six months to states cooperating with Somalia's Transitional Federal Government (TFG) to enter the country's territorial waters and use "all necessary means" to stop "piracy and armed robbery at sea, in a manner consistent with international law."[69]

- Several more piracy incidents have occurred in 2008 including an Ukrainian ship, the MV Faina, containing an arms consignment for Kenya, including tanks and other heavy weapons, which was possibly heading towards an area of Somalia controlled by the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) after its hijacking by pirates[70] before anchoring off the Somali coast. The Somali pirates—in a standoff with US missile destroyer the USS Howard—asked for a $20 million ransom for the 20 crew members it held; shots were heard from the ship, supposedly because of a dispute between pirates who wanted to surrender and those who didn't.[71] In a separate incident, occurring near the same time (late September to early October), an Iranian cargo ship, MV Iran Deyanat, departing from China, was boarded by pirates off Somalia. The ship's cargo was a matter of dispute, though some pirates have apparently been sickened, lost hair, suffered burns, and even died while on the ship. Speculations of chemical or even radioactive contents have been made.[72]

- On November 15, 2008, Somali pirates seized the supertanker MV Sirius Star, 450 miles off the coast of Kenya. The ship was carrying around $100 million worth of oil and had a 25-man crew. This marked the largest tonnage vessel ever seized by pirates.[73]

- On April 8, 2009, Somali pirates briefly captured the MV Maersk Alabama, a 17,000-ton cargo ship containing emergency relief supplies destined for Kenya. It was the latest in a week-long series of attacks along the Somali coast, and the first of these attacks to target a U.S.-flagged vessel. The crew took back control of the ship although the Captain was taken by the escaping pirates to a lifeboat.[74] On Sunday, April 12, 2009, Capt. Richard Phillips was rescued, reportedly in good condition, from his pirate captors who were shot and killed by US Navy SEAL snipers.[75][76] Vice Admiral William E. Gortney reported the rescue began when Commander Frank Castellano, captain of the Bainbridge, determined that Phillips' life was in imminent danger and ordered the action.

- In July 2009 Finnish-owned ship MV Arctic Sea sailing under Maltese flag was allegedly hijacked in the territorial waters of Sweden by a group of eight to ten pirates disguised as policemen. According to some sources, the pirates held the ship for 12 hours, went through the cargo and later released the ship and the crew.[77] However, an investigation into the incident is underway amidst speculation regarding the ship's actual cargo, allegations of cover-up by Russian authorities and Israeli involvement.

Authorities estimate that only between 50%[78][79] to as low as 10%[80] of pirate attacks are actually reported (so as not to increase insurance premiums).

Successful attempts against piracy

International ships equipped with helicopters patrol the waters where pirate activity has been reported, but the area is very large. Some ships are equipped with anti-piracy weaponry such as a sonic device that sends a sonic wave out to a directed target, creating a sound so powerful that it bursts the eardrums and shocks pirates, causing them to become disoriented enough to drop their weapons, while the vessel being pursued increases speed and engages in evasive maneuvering.[81]

- MS Nautica, December 2008[82]

- US-flagged Maersk Alabama, April 2009,[83] November 2009

- Liberian-registered cargo ship, April 2009[84]

- US-flagged MV Liberty Sun, April 2009 [85]

- The Marshall Islands-flagged Handytankers Magic, April 2009 [86]

Legal authority

There are legal barriers to prosecuting individuals captured in international waters. Countries are struggling to apply existing maritime law, international law, and their own laws, which limits them to having jurisdiction over their own citizens. According to piracy experts, the goal is to "deter and disrupt" pirate activity, and pirates are often detained, interrogated, disarmed, and released. With millions of dollars at stake, pirates have little incentive to stop.

Prosecutions are rare for several reasons. Modern laws against piracy are almost non-existent. For example, the Dutch are using a 17th-century law against "sea robbery" to prosecute. Warships that capture pirates have no jurisdiction to try them, and NATO does not have a detention policy in place. Prosecutors have a hard time assembling witnesses and finding translators, and countries are reluctant to imprison pirates because they would be saddled with them upon their release.[87]

George Mason University professor Peter Leeson has suggested that the international community appropriate Somali territorial waters and sell them, together with the international portion of the Gulf of Aden, to a private company which would then provide security from piracy in exchange for charging tolls to world shipping through the Gulf.[88][89]

Self protection measures and increased patrol

First and foremost, the best protection against piracy is simply to avoid encountering them. This can be done using the regular radar, as well as by using more advanced forms thereof (e.g. BAE Systems HF SWR, BAE Systems PRISM, ... )[90]

In addition, while the non-wartime 20th century tradition has been for merchant vessels not to be armed, the U.S. Government has recently changed the rules so that it is now "best practice" for vessels to embark a team of armed private security guards.[91][92] In addition, the crew themselves can be given a weapons training,[93] and warning shots, less-lethal ammunition, ... can be fired legally in international waters and/or when sailing under Israeli or Russian flag틀:Dubious. Finally, similar to weapons training, remote weapon systems can be implemented to a vessel.[94]

Other measures vessels can take to protect themselves against piracy are implementing a high freewall [95] and vessel boarding protection systems (e.g. hot water wall, electricity-charged water wall, automated fire monitor, slippery foam, ...)[96][97]

Finally, in emergency situations, warships can be called upon. In some areas such as near Somalia, naval vessels from different nations are present that are able to intercept vessels attacking merchant vessels. For patrolling dangerous coastal waters (and/or keeping financial expenses down), robotic or remote-controlled USV's are also sometimes used.[98] Also, both shore-launched and vessel-launched UAV's are also used by the army.[99][100]

Commerce raiders

A wartime activity similar to piracy involves disguised warships called commerce raiders or merchant raiders, which attack enemy shipping commerce, approaching by stealth and then opening fire. Commerce raiders operated successfully during the American Revolution. During the American Civil War, the Confederacy sent out several commerce raiders, the most famous of which was the CSS Alabama. During World War I and World War II, Germany also made use of these tactics, both in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Since commissioned naval vessels were openly used, these commerce raiders should not be considered even privateers, much less pirates—although the opposing combatants were vocal in denouncing them as such.

In international law

Effects on international boundaries

During the 18th century, the British and the Dutch controlled opposite sides of the Straits of Malacca. The British and the Dutch drew a line separating the Straits into two halves. The agreement was that each party would be responsible for combating piracy in their respective half. Eventually this line became the border between Malaysia and Indonesia in the Straits.

Law of nations

Piracy is of note in international law as it is commonly held to represent the earliest invocation of the concept of universal jurisdiction. The crime of piracy is considered a breach of jus cogens, a conventional peremptory international norm that states must uphold. Those committing thefts on the high seas, inhibiting trade, and endangering maritime communication are considered by sovereign states to be hostis humani generis (enemies of humanity).[101]

For a different opinion on Pirates as Hostis Humani Generis see Caninas, Osvaldo Peçanha. Modern Maritime Piracy: History, Present Situation and Challenges to International Law. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the ISA - ABRI JOINT INTERNATIONAL MEETING, Pontifical Catholic University, Rio de Janeiro Campus (PUC-Rio), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Jul 22, 2009

In the United States, criminal prosecution of piracy is authorized in the U.S. Constitution, Art. I Sec. 8 cl. 10:

The Congress shall have Power ... To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations;

In English admiralty law, piracy was defined as petit treason during the medieval period, and offenders were accordingly liable to be drawn and quartered on conviction. Piracy was redefined as a felony during the reign of Henry VIII. In either case, piracy cases were cognizable in the courts of the Lord High Admiral. English admiralty vice-admiralty judges emphasized that "neither Faith nor Oath is to be kept" with pirates; i.e. contracts with pirates and oaths sworn to them were not legally binding. Pirates were legally subject to summary execution by their captors if captured in battle. In practice, instances of summary justice and annulment of oaths and contracts involving pirates do not appear to have been common.

Since piracy often takes place outside the territorial waters of any state, the prosecution of pirates by sovereign states represents a complex legal situation. The prosecution of pirates on the high seas contravenes the conventional freedom of the high seas. However, because of universal jurisdiction, action can be taken against pirates without objection from the flag state of the pirate vessel. This represents an exception to the principle extra territorium jus dicenti impune non paretur (the judgment of one who is exceeding his territorial jurisdiction may be disobeyed with impunity).[102]

In 2008 the British Foreign Office advised the Royal Navy not to detain pirates of certain nationalities as they might be able to claim asylum in Britain under British human rights legislation, if their national laws included execution, or mutilation as a judicial punishment for crimes committed as pirates.[103]

International conventions

UNCLOS Article 101: Definition

In the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982, "maritime piracy" consists of:

- (a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed:

- (i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

- (ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

- (b) any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

- (c) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (a) or (b).[104]

IMB Definition

The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) defines piracy as:

- the act of boarding any vessel with an intent to commit theft or any other crime, and with an intent or capacity to use force in furtherance of that act.[105]

In popular culture

Pirates are a frequent topic in fiction and are associated with certain stereotypical manners of speaking and dress, some of them wholly fictional: "nearly all our notions of their behavior come from the golden age of fictional piracy, which reached its zenith in 1881 with the appearance of Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island."[106] Some inventions of pirate culture such as "walking the plank" were popularized by J. M. Barrie's novel, Peter Pan, where Captain Hook's pirates helped define the fictional pirate archetype.[107] Robert Newton's portrayal of Long John Silver in Disney's 1950 film adaptation of Treasure Island also helped define the modern rendition of a pirate, including the stereotypical "pirate" accent.[107] Other influences include Sinbad the Sailor, and the recent Pirates of the Caribbean films have helped kindle modern interest in piracy and have performed well at the box office. The classic Gilbert and Sullivan operetta The Pirates of Penzance focuses on The Pirate King and his hopeless band of pirates on the South coast of England. The Pirate King is often believed to be inspiration for Jack Sparrow. Pirates are also common mascots and names of sports teams. See also

참조관계 문헌

추천 문헌

주석

바깥 고리

|