사용자:Sulgi/연습장

| 원저자 | Stephen Altschul, Warren Gish, Webb Miller, Eugene Myers, and David Lipman |

|---|---|

| 개발자 | NCBI |

| 안정화 버전 | 2.11.0+

/ 2020년 11월 3일 |

| 프로그래밍 언어 | C and C++[1] |

| 운영 체제 | UNIX, Linux, Mac, MS-Windows |

| 종류 | Bioinformatics tool |

| 라이선스 | Public domain |

| 웹사이트 | blast |

In bioinformatics, BLAST (basic local alignment search tool)[2] is an algorithm and program for comparing primary biological sequence information, such as the amino-acid sequences of proteins or the nucleotides of DNA and/or RNA sequences. A BLAST search enables a researcher to compare a subject protein or nucleotide sequence (called a query) with a library or database of sequences, and identify database sequences that resemble the query sequence above a certain threshold. For example, following the discovery of a previously unknown gene in the mouse, a scientist will typically perform a BLAST search of the human genome to see if humans carry a similar gene; BLAST will identify sequences in the human genome that resemble the mouse gene based on similarity of sequence.

Background[편집]

BLAST, which The New York Times called the Google of biological research,[2] is one of the most widely used bioinformatics programs for sequence searching.[3] It addresses a fundamental problem in bioinformatics research. The heuristic algorithm it uses is much faster than other approaches, such as calculating an optimal alignment. This emphasis on speed is vital to making the algorithm practical on the huge genome databases currently available, although subsequent algorithms can be even faster.

Before BLAST, FASTA was developed by David J. Lipman and William R. Pearson in 1985.[4]

Before fast algorithms such as BLAST and FASTA were developed, searching databases for protein or nucleic sequences was very time consuming because a full alignment procedure (e.g., the Smith–Waterman algorithm) was used.

BLAST came from the 1990 stochastic model of Samuel Karlin and Stephen Altschul[5] They proposed "a method for estimating similarities between the known DNA sequence of one organism with that of another",[2] and their work has been described as "the statistical foundation for BLAST."[6] Subsequently, Altschul, along with Warren Gish, Webb Miller, Eugene Myers, and David J. Lipman at the National Institutes of Health designed the BLAST algorithm, which was published in the Journal of Molecular Biology in 1990 and cited over 75,000 times.[7]

While BLAST is faster than any Smith-Waterman implementation for most cases, it cannot "guarantee the optimal alignments of the query and database sequences" as Smith-Waterman algorithm does. The optimality of Smith-Waterman "ensured the best performance on accuracy and the most precise results" at the expense of time and computer power.

BLAST is more time-efficient than FASTA by searching only for the more significant patterns in the sequences, yet with comparative sensitivity. This could be further realized by understanding the algorithm of BLAST introduced below.

Examples of other questions that researchers use BLAST to answer are:

- Which bacterial species have a protein that is related in lineage to a certain protein with known amino-acid sequence

- What other genes encode proteins that exhibit structures or motifs such as ones that have just been determined

BLAST is also often used as part of other algorithms that require approximate sequence matching.

BLAST is available on the web on the NCBI website. Different types of BLASTs are available according to the query sequences and the target databases. Alternative implementations include AB-BLAST (formerly known as WU-BLAST), FSA-BLAST (last updated in 2006), and ScalaBLAST.[8][9]

The original paper by Altschul, et al.[7] was the most highly cited paper published in the 1990s.[10]

Input[편집]

(FASTA 파일 혹은 Genbank 포맷의) 입력 서열들, 질의대상의 데이터베이스와 스코어링 행렬과 같은 다른 선택적인 파라미터들.

Output[편집]

BLAST output can be delivered in a variety of formats. These formats include HTML, plain text, and XML formatting. For NCBI's web-page, the default format for output is HTML. When performing a BLAST on NCBI, the results are given in a graphical format showing the hits found, a table showing sequence identifiers for the hits with scoring related data, as well as alignments for the sequence of interest and the hits received with corresponding BLAST scores for these. The easiest to read and most informative of these is probably the table.

If one is attempting to search for a proprietary sequence or simply one that is unavailable in databases available to the general public through sources such as NCBI, there is a BLAST program available for download to any computer, at no cost. This can be found at BLAST+ executables. There are also commercial programs available for purchase. Databases can be found from the NCBI site, as well as from Index of BLAST databases (FTP).

프로세스rocess[편집]

BLAST 는 휴리스틱 방법을 사용하여 두 서열 사이의 짧은 일치도를 찾음으로써 유사할 서열들을 찾는다. 유사한 서열을 찾는 이러한 과정을 씨딩 seeding 이라고 한다. 이러한 첫 매치를 찾은 이후에 BLAST 가 로컬 정렬을 하기 시작한다.서열들 사이의 유사성을 찾으려고 노력할 때에, 단어라고 알려진 공통된 단어 집합들이 매우 중요한다. 예를 들어, 한 서열이 다음 글자들, GLKFA 를 포함한다고 하자. BLAST 는 잉ㄹ반적인 상황에서 수행되고 있다면, 단어크기는 3 글자이다. 이 경우, 주어진 글자들을 사용하면 검색 단어들은 GLK, LKF, KFA 가 될 것이다. BLAST 의 휴리스틱 알고리즘은 관심있는 서열들과 히트서열 혹은 데이터베이스에 있는 서열들 사이의 모든 공통된 세글자 단어들의 위치를 찾아낸다. 이 결과를 사용하여 정렬을 만든다. 관심있는 서열을 위한 단어들을 만든 다음에, 단어의 나머지들이 어셈블된다. 이러한 단어들은 스코어링 행렬을 사용하여 비교하여, 최소한 문턱값 T 의 점수를 가져야 한다는 조건을 만족해야한다.

자주 사용되는 BLAST 검색의 스코어링 행렬은 BLOSUM62[11] 이지만, 사실 최적 스코어링 행렬은 서열 유사도에 따라 달라진다. 두 단어와 이웃한 단어들이 어셈들되고 컴파일되면, 매치를 찾기 위해 데이터베이스 안의 서열들과 비교된다. 문턱값 점수 T 는 특정한 단어가 정렬에 포함될지 아닐지를 결정한다. 씨딩이 이루어지면, 3 아미노산으로 이루어진 정렬이 BLAST 가 사용하는 알고리즘을 이용하여 양방향으로 연장된다. 각방향으로 연장되면 점수가 높아지던지 낮아져서 정렬 점수에 영향을 준다. 이 점수가 미리 결정된 문턱값 점수 T 보다 크면, 이 정렬된 것은 BLAST 결과들에 포함될 것이다. 그러나 이 점수가 T 보다 작으면, 정렬이 연장을 멈추어 정렬이 잘 안되는 영역이 BLAST 결과에 포함되지 않도록 한다. T 점수가 증가하면 검색이 가능한 공간의 크기를 제한하고, 이웃 단어들의 수를 감소시키지만, 동시에 BLAST 프로세스의 속도를 증가시킨다.

알고리즘[편집]

BLAST를 구동하기 위해서는 질의 주체가 되는 질의 서열과 (타겟 서열이라고도 부르는) 질의 대상이 되는 서열이나 이러한 서열들을 포함한 서열 데이터베이스가 필요하다. BLAST는 질의 서열의 하위서열들과 유사한 데이터베이스 안의 하위서열들을 찾는 알고리즘이다. 일반적으로 질의 서열은 데이터베이스보다 훨씬 작은데, 예를 들어, 질의서열은 길이가 천 핵산 정도인 반면, 데이터베이스는 수십억 핵산일 수 있다.

BLAST 의 핵심 아이디어는 고득점 조각 쌍 (High-scoring Segment Pairs, HSP) 이 통계적으로 유의하게 정렬되어 포함되어 있다는 것이다. BLAST는 스미스-워터맨 알고리즘Smith-Waterman algorithm을 근사하는 휴리스틱 heuristic 방법을 사용하여 질의 서열과 데이터베이스 안에 존재하는 서열들 사이의 고득점 정렬서열들 sequence alignments 을 찾는다. 그러나 모든 것을 다 살펴보는 스미스-워터맨 알고리즘은 GenBank와 같은 대용량의 유전체 데이터베이스를 검색하는데에는 너무 느리다. 따라서 BLAST 알고리즘은 스미스-워터맨 알고리즘보다 덜 정확하지만 50 배 이상 빠른 휴리스틱 방법을 사용한다. [8] BLAST의 속도와 상대적으로 나쁘지 않은 정확도때문에 BLAST 를 기반으로 한 프로그램들이 혁신적인 기술로 평가를 받는다.

An overview of the BLAST algorithm (a protein to protein search) is as follows:[12]

- 질의 서열 안에 있는 낮은 복잡도 영역이나 서열 반복을 제거한다.

- "Low-complexity region" means a region of a sequence composed of few kinds of elements. These regions might give high scores that confuse the program to find the actual significant sequences in the database, so they should be filtered out. The regions will be marked with an X (protein sequences) or N (nucleic acid sequences) and then be ignored by the BLAST program. To filter out the low-complexity regions, the SEG program is used for protein sequences and the program DUST is used for DNA sequences. On the other hand, the program XNU is used to mask off the tandem repeats in protein sequences.

- 질의 서열의 k-letter 단어 리스트를 만든다.

- 예를 들어 k=3 이라고 하면, 질의 단백질 서열 안에 있는 길이가 3 인 (DNA 서열에서는 k 는 통상 11이다) 단어들을, 질의 서열의 마지막 문자가 포함될 때까지 "순서대로" 나열한다. 이 방법은 figure 1 에 그림으로 표현되어 있다.

Fig. 1 The method to establish the k-letter query word list.[13]

- 예를 들어 k=3 이라고 하면, 질의 단백질 서열 안에 있는 길이가 3 인 (DNA 서열에서는 k 는 통상 11이다) 단어들을, 질의 서열의 마지막 문자가 포함될 때까지 "순서대로" 나열한다. 이 방법은 figure 1 에 그림으로 표현되어 있다.

- 가능한 매치가 되는 단어들을 나열한다.

- 이 과정이 BLAST 와 FASTA 의 주요 차이점 중 하나이다. FASTA 는 데이터베이스 안의 공통된 단어들 모두와 2단계에서 나열한 질의서열을 고려하지만, BLAST 는 점수가 높은 단어들만 고려한다. 이 점수는 2단계의 리스트에 있는 단어와 모든 3 글자 단어들을 비교하여 만들어진다. 스코어 행렬 (substitution matrix) 을 사용하여, 각 산출물 쌍의 비교를 점수화 하면, 3-글자 단어에 대해 20^3 개의 가능한 매치 스코어가 생긴다. 예를 들어, PQG 를 PEG 와 PQA 와 비교하여 구하는 점수는 BLOSUM62 가중법에 따르면 각각 15 와 12 이다. DNA 단어의 경우, 매치는 +5 점, 미스매치는 -4 혹은, +2 와 -3 점이 된다. 이후, 가능한 매치되는 단어들의 수를 줄이기 위해, 이웃 단어 점수 임계치 T 를 사용한다. 점수가 임계치 T 보다 큰 단어들은 가능한 매칭되는 단어 리스트에 남게 되고, 이보다 낮은 점수를 가진 단어들은 버려지게 된다. 예를들어, T 가 13이면 PEG 는 남게되지만, PQA 는 버려진다.

- 남은 고득점 단어들을 정리하여 효율적인 검색 트리로 만든다.

- This allows the program to rapidly compare the high-scoring words to the database sequences.

- 질의 서열에 있는 k-글자 단어 각각에 대해 3단계와 4단계를 반복한다.

- 남은 고득점 단어들과 정확하게 매치되는 데이터베이스 서열이 있는지 스캔한다.

- 블라스트 프로그램은 각 위치에서 PEG 와 같이 남아있는 고득점 단어에 대해 데이터베이스를 스캔한다. 정확한 매치가 발견되면, 이 매치를 질의서열과 데이터베이스 서열들 사이의 가능한 틈이 없는 (un-gapped) 정렬에 시드가 되는 데에 사용한다.

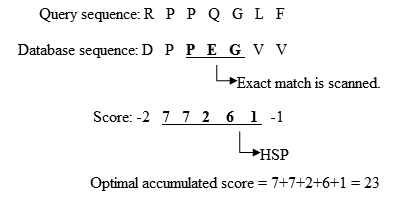

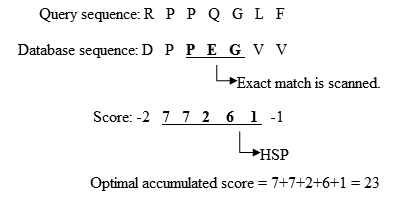

- 정확한 매치들을 고득점 조각 쌍 (High-scoring segment pair, HSP) 로 연장한다.

- BLAST 원래 버전은 질의서열과 데이터베이스 서열 사이의 연장 정렬을 정확한 매치가 일어난 곳에서부터 왼쪽 방향과 오른쪽 방향으로 연장한다. HSP 의 누적 전체 점수가 감소하기 시작할 때까지 계속 연장된다. 간단한 예시가 그림 2에 표현되어 있다.

Fig. 2 The process to extend the exact match. Adapted from Biological Sequence Analysis I, Current Topics in Genome Analysis [2].

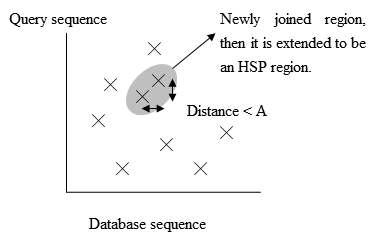

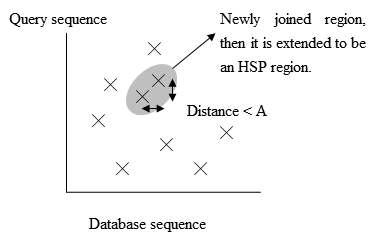

Fig. 3 The positions of the exact matches. - 시간을 더 아끼기 위해, BLAST2 혹은 갭이 있는 (gapped) BLAST라고 불리는 새로운 버전이 개발되었다. BLAST2 는 유사한 서열을 탐지하는데에 같은 수준의 민감도를 유지하기 위해 더 낮은 이웃 단어 점수 기준 (threshold) 을 차용한다. 따라서 3단계에서 가능한 매치되는 단어 리스트는 길어진다. 다음으로, figure 3 의 같은 대각선에 있는 서로 A 거리 내의 정확하게 매치된 구간들은 더 긴 새로운 구간으로 합쳐질 것이다. 마지막으로, BLAST 의 원래 버전에서 사용된 같은 방법을 사용하여 새로운 구간들은 연장되고, 이 구간들의 HSP들은 전과 같은 대치 행렬을 사용하여 만들어진다.

- BLAST 원래 버전은 질의서열과 데이터베이스 서열 사이의 연장 정렬을 정확한 매치가 일어난 곳에서부터 왼쪽 방향과 오른쪽 방향으로 연장한다. HSP 의 누적 전체 점수가 감소하기 시작할 때까지 계속 연장된다. 간단한 예시가 그림 2에 표현되어 있다.

- 데이터베이스 안에서 점수가 충분히 높은 모든 HSP 들을 나열한다.

- 점수가 실험적으로 결정된 컷오프 점수 S 보다 큰 HSP 들을 나열한다.

- 임의의 서열들을 비교하여 모델한 정렬점수 분포를 조사하여, 컷오프 점수 S가 남은 HSP 들의 유의성을 충분히 보장할 수 있는 높은 값으로 결정할 수 있다.

- HSP 점수의 유의성을 평가한다.

- BLAST 는 다음으로 Gumbel 의 극단적 값 분포 (extreme value distribution, EVD) 를 이용하여 각 HSP 값들의 통계적 유의성을 평가한다. (임의의 두 서열 사이에 스미스-워터맨 로컬 정렬 값의 분포가 Gumbel 의 EVD 를 따른다는 것이 증명되었다. 갭을 포함하는 로컬 정렬에 대해서는 증명되지 않았다). Gumbel 의 EVD 에 따라, S 점수가 equal to or greater than x 와 같거나 클 확률 p 는 다음 등식이 된다

- where

- 통계 모수 와 는 질의 서열과 많은 데이터베이스 서열의 섞은 버전들 (전역 혹은 지역 섞음) 의 갭이 없는 로컬 정렬 값들의 분포를 Gumbel 극단 값 분포에 적합시켜서 추정한다. 과 는 대치 행렬, 갭 패널티들, 서열 구성 (문자 빈도)에 의존한다. 과 는 각각 질의서열과 데이터베이스 서열들의 실효 길이이다. 원 서열 길이는 엣지 효과를 벌충하기 위해 실효길이로 줄인다 (질의나 데이터베이스 서열 중 하나의 끝에 가까운 곳에서 시작된 정렬은 최적 정렬을 구성하기에 충분하지 않게 된다). 이것들은 다음과 같이 계산할 수 있다

- where is the average expected score per aligned pair of residues in an alignment of two random sequences. Altschul 와 Gish 는 갭이 없는 로컬 정렬에 대해 BLOSUM62 를 대치 행렬로 사용하여 다음과 같은 일반적인 값들을 제시했다, , , and . 유의성을 평가하는데 이러한 일반적인 값들을 사용하는 것은 룩업 테이블 방법이라고 하는데 이는 정확하지 않게 된다. 데이터베이스 매치의 기대 값 (expect value) E 는 관계없는 데이터베이스 서열의 점수 S 가 우연히 x 보다 크게될 경우의 수이다. D 개 서열의 데이터베이스를 질의하는데서 구한 기대값 E 는 다음과 같이 주어진다

- 한발 더 나아가면, 일때, E 는 다음과 같이 Poisson 분포로 근사할 수 있다

- 갭이 없는 지역 정렬의 HSP 점수 유의성을 평가하는 기대값 "E" (E score, E-value 혹은 e-value 라고 불림) 는 BLAST 결과에 포함된다. 통계적 모수들의 변동 때문에 개별 HSP들이 여기서 보여주는 계산은 is modified if individual HSPs are combined, such as when producing gapped alignments (described below), due to the variation of the statistical parameters.

- BLAST 는 다음으로 Gumbel 의 극단적 값 분포 (extreme value distribution, EVD) 를 이용하여 각 HSP 값들의 통계적 유의성을 평가한다. (임의의 두 서열 사이에 스미스-워터맨 로컬 정렬 값의 분포가 Gumbel 의 EVD 를 따른다는 것이 증명되었다. 갭을 포함하는 로컬 정렬에 대해서는 증명되지 않았다). Gumbel 의 EVD 에 따라, S 점수가 equal to or greater than x 와 같거나 클 확률 p 는 다음 등식이 된다

- 두개 이상의 HSP 구간을 정렬된 하나의 구간으로 연장한다.

- Sometimes, we find two or more HSP regions in one database sequence that can be made into a longer alignment. This provides additional evidence of the relation between the query and database sequence. There are two methods, the Poisson method and the sum-of-scores method, to compare the significance of the newly combined HSP regions. Suppose that there are two combined HSP regions with the pairs of scores (65, 40) and (52, 45), respectively. The Poisson method gives more significance to the set with the maximal lower score (45>40). However, the sum-of-scores method prefers the first set, because 65+40 (105) is greater than 52+45(97). The original BLAST uses the Poisson method; gapped BLAST and the WU-BLAST uses the sum-of scores method.

- 질의 서열과 이와 매치된 데이터베이스 서열들의 갭이 있는 스미스-워터맨 지역 정렬한 것들을 보여준다.

- The original BLAST only generates un-gapped alignments including the initially found HSPs individually, even when there is more than one HSP found in one database sequence.

- BLAST2 produces a single alignment with gaps that can include all of the initially found HSP regions. Note that the computation of the score and its corresponding E-value involves use of adequate gap penalties.

- 기대점수가 문턱값 파라미터 E 값보다 작은 모든 매치된 것들을 보고한다.

Parallel BLAST[편집]

Parallel BLAST versions of split databases are implemented using MPI and Pthreads, and have been ported to various platforms including Windows, Linux, Solaris, Mac OS X, and AIX. Popular approaches to parallelize BLAST include query distribution, hash table segmentation, computation parallelization, and database segmentation (partition). Databases are split into equal sized pieces and stored locally on each node. Each query is run on all nodes in parallel and the resultant BLAST output files from all nodes merged to yield the final output. Specific implementations include MPIblast, ScalaBLAST, DCBLAST and so on.[14]

Program[편집]

The BLAST program can either be downloaded and run as a command-line utility "blastall" or accessed for free over the web. The BLAST web server, hosted by the NCBI, allows anyone with a web browser to perform similarity searches against constantly updated databases of proteins and DNA that include most of the newly sequenced organisms.

The BLAST program is based on an open-source format, giving everyone access to it and enabling them to have the ability to change the program code. This has led to the creation of several BLAST "spin-offs".

There are now a handful of different BLAST programs available, which can be used depending on what one is attempting to do and what they are working with. These different programs vary in query sequence input, the database being searched, and what is being compared. These programs and their details are listed below:

BLAST is actually a family of programs (all included in the blastall executable). These include:[15]

- Nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST (blastn)

- This program, given a DNA query, returns the most similar DNA sequences from the DNA database that the user specifies.

- Protein-protein BLAST (blastp)

- This program, given a protein query, returns the most similar protein sequences from the protein database that the user specifies.

- Position-Specific Iterative BLAST (PSI-BLAST) (blastpgp)

- This program is used to find distant relatives of a protein. First, a list of all closely related proteins is created. These proteins are combined into a general "profile" sequence, which summarises significant features present in these sequences. A query against the protein database is then run using this profile, and a larger group of proteins is found. This larger group is used to construct another profile, and the process is repeated.

- By including related proteins in the search, PSI-BLAST is much more sensitive in picking up distant evolutionary relationships than a standard protein-protein BLAST.

- Nucleotide 6-frame translation-protein (blastx)

- This program compares the six-frame conceptual translation products of a nucleotide query sequence (both strands) against a protein sequence database.

- Nucleotide 6-frame translation-nucleotide 6-frame translation (tblastx)

- This program is the slowest of the BLAST family. It translates the query nucleotide sequence in all six possible frames and compares it against the six-frame translations of a nucleotide sequence database. The purpose of tblastx is to find very distant relationships between nucleotide sequences.

- Protein-nucleotide 6-frame translation (tblastn)

- This program compares a protein query against the all six reading frames of a nucleotide sequence database.

- Large numbers of query sequences (megablast)

- When comparing large numbers of input sequences via the command-line BLAST, "megablast" is much faster than running BLAST multiple times. It concatenates many input sequences together to form a large sequence before searching the BLAST database, then post-analyzes the search results to glean individual alignments and statistical values.

Of these programs, 틀:Citation needed span because they use direct comparisons, and do not require translations. However, since protein sequences are better conserved evolutionarily than nucleotide sequences, tBLASTn, tBLASTx, and BLASTx, produce more reliable and accurate results when dealing with coding DNA. They also enable one to be able to directly see the function of the protein sequence, since by translating the sequence of interest before searching often gives you annotated protein hits.

Alternative versions[편집]

A version designed for comparing large genomes or DNA is BLASTZ.

CS-BLAST (Context-Specific BLAST) is an extended version of BLAST for searching protein sequences that finds twice as many remotely related sequences as BLAST at the same speed and error rate. In CS-BLAST, the mutation probabilities between amino acids depend not only on the single amino acid, as in BLAST, but also on its local sequence context. Washington University produced an alternative version of NCBI BLAST, called WU-BLAST. The rights have since been acquired to Advanced Biocomputing, LLC.

In 2009, NCBI has released a new set of BLAST executables, the C++ based BLAST+, and has released C versions until 2.2.26.[16] Starting with version 2.2.27 (April 2013), only BLAST+ executables are available. Among the changes is the replacement of the blastall executable with separate executables for the different BLAST programs, and changes in option handling. The formatdb utility (C based) has been replaced by makeblastdb (C++ based) and databases formatted by either one should be compatible for identical blast releases. The algorithms remain similar, however, the number of hits found and their order can vary significantly between the older and the newer version. BLAST+ since

Accelerated versions[편집]

TimeLogic offers an FPGA-accelerated implementation of the BLAST algorithm called Tera-BLAST that is hundreds of times faster.

Other formerly supported versions include:

- FPGA-accelerated

- Prior to their acquisition by Qiagen, CLC bio collaborated with SciEngines GmbH on an FPGA accelerator they claimed will give 188x acceleration of BLAST.

- The Mitrion-C Open Bio Project was an effort to port BLAST to run on Mitrion FPGAs.

- GPU-accelerated

- GPU-Blast[17] is an accelerated version of NCBI BLASTP for CUDA which is 3x~4x faster than NCBI Blast.

- CUDA-BLASTP[18] is a version of BLASTP that is GPU-accelerated and is claimed to run up to 10x faster than NCBI BLAST.

- G-BLASTN[19] is an accelerated version of NCBI blastn and megablast, whose speedup varies from 4x to 14x (compared to the same runs with 4 CPU threads). Its current limitation is that the database must fit into the GPU memory.

- CPU-accelerated

- MPIBlast is a parallel implementation of NCBI BLAST using Message Passing Interface. By efficiently utilizing distributed computational resources through database fragmentation, query segmentation, intelligent scheduling, and parallel I/O, mpiBLAST improves NCBI BLAST performance by several orders of magnitude while scaling to hundreds of processors.

- CaBLAST[20] makes search on large databases orders of magnitude faster by exploiting redundancy in data.

- Paracel BLAST was a commercial parallel implementation of NCBI BLAST, supporting hundreds of processors.

- QuickBLAST (kblastp) from NCBI is an implementation accelerated by prefiltering based on Jaccard index estimates with hashed pentameric fragments. The filtering slightly reduces sensitivity, but increases performance by an order of magnitude.[21] NCBI only makes the search available on their non-redundant (nr) protein collection, and does not offer downloads.

Alternatives to BLAST[편집]

The predecessor to BLAST, FASTA, can also be used for protein and DNA similarity searching. FASTA provides a similar set of programs for comparing proteins to protein and DNA databases, DNA to DNA and protein databases, and includes additional programs for working with unordered short peptides and DNA sequences. In addition, the FASTA package provides SSEARCH, a vectorized implementation of the rigorous Smith-Waterman algorithm. FASTA is slower than BLAST, but provides a much wider range of scoring matrices, making it easier to tailor a search to a specific evolutionary distance.

An extremely fast but considerably less sensitive alternative to BLAST is BLAT (Blast Like Alignment Tool). While BLAST does a linear search, BLAT relies on k-mer indexing the database, and can thus often find seeds faster.[22] Another software alternative similar to BLAT is PatternHunter.

Advances in sequencing technology in the late 2000s has made searching for very similar nucleotide matches an important problem. New alignment programs tailored for this use typically use BWT-indexing of the target database (typically a genome). Input sequences can then be mapped very quickly, and output is typically in the form of a BAM file. Example alignment programs are BWA, SOAP, and Bowtie.

For protein identification, searching for known domains (for instance from Pfam) by matching with Hidden Markov Models is a popular alternative, such as HMMER.

An alternative to BLAST for comparing two banks of sequences is PLAST. PLAST provides a high-performance general purpose bank to bank sequence similarity search tool relying on the PLAST[23] and ORIS[24] algorithms. Results of PLAST are very similar to BLAST, but PLAST is significantly faster and capable of comparing large sets of sequences with a small memory (i.e. RAM) footprint.

For applications in metagenomics, where the task is to compare billions of short DNA reads against tens of millions of protein references, DIAMOND[25] runs at up to 20,000 times as fast as BLASTX, while maintaining a high level of sensitivity.

The open-source software MMseqs is an alternative to BLAST/PSI-BLAST, which improves on current search tools over the full range of speed-sensitivity trade-off, achieving sensitivities better than PSI-BLAST at more than 400 times its speed.[26]

Optical computing approaches have been suggested as promising alternatives to the current electrical implementations. OptCAM is an example of such approaches and is shown to be faster than BLAST.[27]

Comparing BLAST and the Smith-Waterman Process[편집]

While both Smith-Waterman and BLAST are used to find homologous sequences by searching and comparing a query sequence with those in the databases, they do have their differences.

Due to the fact that BLAST is based on a heuristic algorithm, the results received through BLAST, in terms of the hits found, may not be the best possible results, as it will not provide you with all the hits within the database. BLAST misses hard to find matches.

A better alternative in order to find the best possible results would be to use the Smith-Waterman algorithm. This method varies from the BLAST method in two areas, accuracy and speed. The Smith-Waterman option provides better accuracy, in that it finds matches that BLAST cannot, because it does not miss any information. Therefore, it is necessary for remote homology. However, when compared to BLAST, it is more time consuming, not to mention that it requires large amounts of computer usage and space. However, technologies to speed up the Smith-Waterman process have been found to improve the time necessary to perform a search dramatically. These technologies include FPGA chips and SIMD technology.

In order to receive better results from BLAST, the settings can be changed from their default settings. However, there is no given or set way of changing these settings in order to receive the best results for a given sequence. The settings available for change are E-Value, gap costs, filters, word size, and substitution matrix. Note, that the algorithm used for BLAST was developed from the algorithm used for Smith-Waterman. BLAST employs an alignment which finds "local alignments between sequences by finding short matches and from these initial matches (local) alignments are created".[28]

BLAST output visualization[편집]

To help users interpreting BLAST results, different software is available. According to installation and use, analysis features and technology, here are some available tools:[29]

- NCBI BLAST service

- general BLAST output interpreters, GUI-based: JAMBLAST, Blast Viewer, BLASTGrabber

- integrated BLAST environments: PLAN, BlastStation-Free, SequenceServer

- BLAST output parsers: MuSeqBox, Zerg, BioParser, BLAST-Explorer

- specialized BLAST-related tools: MEGAN, BLAST2GENE, BOV, Circoletto

Example visualisations of BLAST results are shown in Figure 4 and 5.

Uses of BLAST[편집]

BLAST can be used for several purposes. These include identifying species, locating domains, establishing phylogeny, DNA mapping, and comparison.

- Identifying species

- With the use of BLAST, you can possibly correctly identify a species or find homologous species. This can be useful, for example, when you are working with a DNA sequence from an unknown species.

- Locating domains

- When working with a protein sequence you can input it into BLAST, to locate known domains within the sequence of interest.

- Establishing phylogeny

- Using the results received through BLAST you can create a phylogenetic tree using the BLAST web-page. Phylogenies based on BLAST alone are less reliable than other purpose-built computational phylogenetic methods, so should only be relied upon for "first pass" phylogenetic analyses.

- DNA mapping

- When working with a known species, and looking to sequence a gene at an unknown location, BLAST can compare the chromosomal position of the sequence of interest, to relevant sequences in the database(s). NCBI has a "Magic-BLAST" tool built around BLAST for this purpose.[30]

- Comparison

- When working with genes, BLAST can locate common genes in two related species, and can be used to map annotations from one organism to another.

See also[편집]

References[편집]

- ↑ “BLAST Developer Information”. 《blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov》.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Douglas Martin (2008년 2월 21일). “Samuel Karlin, Versatile Mathematician, Dies at 83”. 《The New York Times》.

- ↑ R. M. Casey (2005). “BLAST Sequences Aid in Genomics and Proteomics”. Business Intelligence Network.

- ↑ Lipman, DJ; Pearson, WR (1985). “Rapid and sensitive protein similarity searches”. 《Science》 227 (4693): 1435–41. Bibcode:1985Sci...227.1435L. doi:10.1126/science.2983426. PMID 2983426.

- ↑ “BLAST topics”.

- ↑ Dan Stober (2008년 1월 16일). “Sam Karlin, mathematician who improved DNA analysis, dead at 83”. 《Stanford.edu》.

- ↑ 가 나 Stephen Altschul; Warren Gish; Webb Miller; Eugene Myers; David J. Lipman (1990). “Basic local alignment search tool”. 《Journal of Molecular Biology》 215 (3): 403–410. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. PMID 2231712.

- ↑ Oehmen, C.; Nieplocha, J. (2006). “ScalaBLAST: A Scalable Implementation of BLAST for High-Performance Data-Intensive Bioinformatics Analysis”. 《IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems》 17 (8): 740. doi:10.1109/TPDS.2006.112. S2CID 11122366.

- ↑ Oehmen, C. S.; Baxter, D. J. (2013). “ScalaBLAST 2.0: Rapid and robust BLAST calculations on multiprocessor systems”. 《Bioinformatics》 29 (6): 797–798. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt013. PMC 3597145. PMID 23361326.

- ↑ “Sense from Sequences: Stephen F. Altschul on Bettering BLAST”. ScienceWatch. July–August 2000. 2007년 10월 7일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ Steven Henikoff; Jorja Henikoff (1992). “Amino Acid Substitution Matrices from Protein Blocks”. 《PNAS》 89 (22): 10915–10919. Bibcode:1992PNAS...8910915H. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. PMC 50453. PMID 1438297.

- ↑ Mount, D. W. (2004). 《Bioinformatics: Sequence and Genome Analysis》 2판. Cold Spring Harbor Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-712-9.

- ↑ Adapted from Biological Sequence Analysis I, Current Topics in Genome Analysis [1].

- ↑ Yim, WC; Cushman, JC (2017). “Divide and Conquer (DC) BLAST: fast and easy BLAST execution within HPC environments”. 《PeerJ》 5: e3486. doi:10.7717/peerj.3486. PMC 5483034. PMID 28652936.

- ↑ “Program Selection Tables of the Blast NCBI web site”.

- ↑ Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T. L. (2009). “BLAST+: Architecture and applications”. 《BMC Bioinformatics》 10: 421. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. PMC 2803857. PMID 20003500.

- ↑ Vouzis, P. D.; Sahinidis, N. V. (2010). “GPU-BLAST: using graphics processors to accelerate protein sequence alignment”. 《Bioinformatics》 27 (2): 182–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq644. PMC 3018811. PMID 21088027.

- ↑ Liu W, Schmidt B, Müller-Wittig W (2011). “CUDA-BLASTP: accelerating BLASTP on CUDA-enabled graphics hardware”. 《IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform》 8 (6): 1678–84. doi:10.1109/TCBB.2011.33. PMID 21339531. S2CID 18221547.

- ↑ Zhao K, Chu X (May 2014). “G-BLASTN: accelerating nucleotide alignment by graphics processors”. 《Bioinformatics》 30 (10): 1384–91. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu047. PMID 24463183.

- ↑ Loh PR, Baym M, Berger B (July 2012). “Compressive genomics”. 《Nat. Biotechnol.》 30 (7): 627–30. doi:10.1038/nbt.2241. PMID 22781691.

- ↑ Madden, Tom; Boratyn, Greg (2017). “QuickBLASTP: Faster Protein Alignments” (PDF). 《Proceedings of NIH Research Festival》. 2019년 5월 16일에 확인함. Abstract page

- ↑ Kent, W. James (2002년 4월 1일). “BLAT—The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool”. 《Genome Research》 (영어) 12 (4): 656–664. doi:10.1101/gr.229202. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 187518. PMID 11932250.

- ↑ Lavenier, D.; Lavenier, Dominique (2009). “PLAST: parallel local alignment search tool for database comparison”. 《BMC Bioinformatics》 10: 329. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-10-329. PMC 2770072. PMID 19821978.

- ↑ Lavenier, D. (2009). 〈Ordered index seed algorithm for intensive DNA sequence comparison〉 (PDF). 《2008 IEEE International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing》 (PDF). 1–8쪽. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.155.3633. doi:10.1109/IPDPS.2008.4536172. ISBN 978-1-4244-1693-6. S2CID 10804289.

- ↑ Buchfink, Xie and Huson (2015). “Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND”. 《Nature Methods》 12 (1): 59–60. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3176. PMID 25402007. S2CID 5346781.

- ↑ Steinegger, Martin; Soeding, Johannes (2017년 10월 16일). “MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets”. 《Nature Biotechnology》 35 (11): 1026–1028. doi:10.1038/nbt.3988. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002E-1967-3. PMID 29035372. S2CID 402352.

- ↑ Maleki, Ehsan; Koohi, Somayyeh; Kavehvash, Zahra; Mashaghi, Alireza (2020). “OptCAM: An ultra‐fast all‐optical architecture for DNA variant discovery”. 《Journal of Biophotonics》 13 (1): e201900227. doi:10.1002/jbio.201900227. PMID 31397961.

- ↑ “Bioinformatics Explained: BLAST versus Smith-Waterman” (PDF). 2007년 7월 4일.

- ↑ Neumann, Kumar and Shalchian-Tabrizi (2014). “BLAST output visualization in the new sequencing era”. 《Briefings in Bioinformatics》 15 (4): 484–503. doi:10.1093/bib/bbt009. PMID 23603091.

- ↑ “NCBI Magic-BLAST”. 《ncbi.github.io》. 2019년 5월 16일에 확인함.

External links[편집]

| Sequence alignment 관련 도서관 자료 |

- Sulgi/연습장 - 공식 웹사이트

- BLAST+ executables — free source downloads