사용자:설총/연습장

이슈타르의 문[편집]

중세 중기[편집]

중세 초기[편집]

중세 말기[편집]

몽골의 정복 전쟁[편집]

| 몽골의 정복 전쟁 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

몽골 제국의 확장 | |||||||

| |||||||

몽골의 정복 전쟁은 13세기 동안 일어났으며, 결과적으로 각각 다른 몽골 제국들이 아시아서부터 동유럽에 걸쳐 지배하게 되었다. 역사가들은 몽골의 침략과 정복을 인류사에 걸쳐 가장 치명적인 충돌 중 하나로 간주한다. 몽골 제국의 영토는 중국(원나라, 14세기), 페르시아 (티무르 왕조, 15세기)와 러시아(타타르 문화의 반영) 및 인도에서 19 세기에 무굴 제국 ).

팍스[편집]

사라진 히치하이커[편집]

사라진 히치하이커 혹은 귀신 히치하이커, 유령 히치하이커 혹은 히치하이커 라는 이야기는 도시괴담으로 운전자가 자동차로 여행 중 히치하이커와 동반을 하면서 이야기는 시작된다. 그러나 히치하이커는 운전 후 목적지에 다다르면 아무런 설명도 없이 사라진다. 사라진 히치하이커 이야기는 백여년간 전세계에 걸쳐 여러한 변형된 이야기가 있으며, 대중 문화 속에 도시전설의 인기와 확산을 보여주는 예이다.

이 이야기가 대중적으로 알려지게 된 계기는 1981년 얀 헤럴드 브룬번드의 책인 사라진 히치하이커(The Vanishing Hitchhiker)로 이 책은 도시전설을 대중이 인식하도록 시작했다.

내용[편집]

전형적이며 현대적인 사라진 히치하이커의 내용의 주인공은 혼자 밤에 헤드라이트를 키며 운전을 하다 히치하이커가 서있는 것을 보게되어 차를 세우고 히치하이커를 태운다. 전체적으로 조용한 상황에서 여행을 계속하는 가운데, 대개 목적지에 다다르면 히치하이커는 차가 움직이는 도중 사라진다.

이는 다른 버전을 동반하는 경우가 많다. A common variation of the above involves the vanishing hitchhiker departing as would a normal passenger, having left some item in the car, or having borrowed a garment for protection against alleged cold (whether or not the weather conditions reflect this claim). The vanishing hitchhiker can also leave some form of information that allegedly encourages the motorist to make subsequent contact.

In such tellings, the garment borrowed is often subsequently found draped over a gravestone in a local cemetery. In this and in the instance of "imparted information", the unsuspecting motorist subsequently makes contact with the family of a deceased person and finds that their passenger fits the description of a family member killed in some unexpected way (usually a car accident) and that the driver's encounter with the vanishing hitchhiker occurred on the anniversary of their death.

Not all vanishing hitchhiker reports involved allegedly recurring ghosts. One popular variant in Hawaii involves the goddess Pele, traveling the roads incognito and rewarding kind travelers. Other variants include hitchhikers who utter prophecies (typically of pending catastrophe or other evils) before vanishing.

Paranormal researcher Michael Goss in his book The Evidence for Phantom Hitch-Hikers discovered that many reports of vanishing hitch-hikers turn out be based on folklore and hearsay stories. Goss also examined some cases and attributed them to a hallucination of the experiencer.[1]

이야기의 분류[편집]

The first proper study of the story of the vanishing hitchhiker was undertaken in 1942-3 by American folklorists Richard Beardsley and Rosalie Hankey, who collected as many accounts as they could and attempted to analyze them.

The Beardsley-Hankey survey elicited 79 written accounts of encounters with vanishing hitchhikers, drawn from across the USA.

They found: "Four distinctly different versions, distinguishable because of obvious differences in development and essence."

These are described as:

- A. Stories where the hitch-hiker [sic] gives an address through which the motorist learns he has just given a lift to a ghost.

- 49 of the Beardsley-Hankey samples fell into this category, with responses from 16 states of the USA.

- B. Stories where the hitch-hiker is an old woman who prophesies disaster or the end of World War II; subsequent inquiries likewise reveal her to be deceased.

- Nine of the samples fit this description, and eight of these came from the vicinity of Chicago. Beardsley and Hankey felt that this indicated a local origin, which they dated to approximately 1933: two of the version B hitchhikers in this sample foretold disaster at the Century of Progress Exposition and another foresaw calamity "at the World's Fair". The strict topicality of these unsuccessful forecasts did not appear to thwart the appearance of further Version 'B' hitch-hikers, one of whom warned that Northerly Island, in Lake Michigan, would soon be submerged (this never happened).

- C. Stories where a girl is met at some place of entertainment, e.g., dance, instead of on the road; she leaves some token (often the overcoat she borrowed from the motorist) on her grave by way of corroborating the experience and her identity.

- The uniformity amongst separate accounts of this variant led Beardsley and Hankey to strongly doubt its folkloric authenticity.

- D. Stories where the hitch-hiker is later identified as a local divinity.

- E. Where a driver gives a girl a lift and drops her off but she leaves something in the car, the driver must return it to her house but when he gets to the house, no one answers. Soon, the driver finds that the girl died when she got out of the car.

Beardsley and Hankey were particularly interested to note one instance (location: Kingston, New York, 1941) in which the vanishing hitchhiker was subsequently identified as the late Mother Cabrini, founder of the local Sacred Heart Orphanage, who was beatified for her work. The authors felt that this was a case of Version 'B' glimpsed in transition to Version 'D'.

Beardsley and Hankey concluded that Version 'A' was closest to the original form of the story, containing the essential elements of the legend. Version 'B' and 'D', they believed, were localized variations, while 'C' was supposed to have started life as a separate ghost story which at some stage became conflated with the original vanishing hitchhiker story (Version 'A').

One of their conclusions certainly seems reflected in the continuation of vanishing hitchhiker stories: The hitchhiker is, in the majority of cases, female and the lift-giver male. Beardsley and Hankey's sample contained 47 young female apparitions, 14 old lady apparitions, and 14 more of an indeterminate sort.

Ernest W Baughman's Type- and Motif-Index of the Folk Tales of England and North America (1966) delineates the basic vanishing hitchhiker as follows:

- "Ghost of young woman asks for ride in automobile, disappears from closed car without the driver's knowledge, after giving him an address to which she wishes to be taken. The driver asks person at the address about the rider, finds she has been dead for some time. (Often the driver finds that the ghost has made similar attempts to return, usually on the anniversary of death in automobile accident. Often, too, the ghost leaves some item such as a scarf or traveling bag in the car.)"

Baughman's classification system grades this basic story as motif E332.3.3.1.

Subcategories include:

- E332.3.3.1(a) for vanishing hitchhikers who reappear on anniversaries;

- E332.3.3.1(b) for vanishing hitchhikers who leave items in vehicles, unless the item is a pool of water in which case it is E332.3.3.1(c);

- E332.3.3.1(d) is for accounts of sinister old ladies who prophesy disasters;

- E332.3.3.1(e) contains accounts of phantoms who are apparently sufficiently solid to engage in activities such as eating or drinking during their journey;

- E332.3.3.1(f) is for phantom parents who want to be taken to the sickbed of their dying son;

- E332.3.3.1(g) is for hitchhikers simply requesting a lift home;

- E332.3.3.1(h-j) are a category reserved exclusively for vanishing nuns (a surprisingly common variant), some of whom foretell the future.

Here, the phenomenon blends into religious encounters, with the next and last vanishing hitchhiker classification - E332.3.3.2 - being for encounters with divinities who take to the road as hitchhikers. The legend of St. Christopher is considered one of these, and the story of Philip the Apostle being transported by God after encountering the Ethiopian on the road (Acts 8:26-39) is sometimes similarly interpreted.[2]

Prophetic hitchhikers since 1970s[편집]

The vanishing hitchhiker phenomenon took on a decidedly divinatory cast during the 1970s and early 1980s.

- 1975 saw a rash of reports of a prophetic nun vanishing from cars after hitching lifts near the Austrian-German border. On 13 April that year, after a 43-year-old businessman drove his car off the road in fright at the disappearance of his passenger, Austrian police threatened a fine equivalent to £200 (1975 value) to anyone reporting similar stories.

- In early 1977, nearly a dozen motorists in and around Milan reported giving lifts to another vanishing nun, who (prior to her unexpected disappearance) forewarned her benefactors of the impending destruction of Milan by earthquake on 27 February (this disaster did not happen) (La Stampa, 25 and 26 February, 1 March 1977; Dallas Morning News 25 February 1977).

- In 1979, near Little Rock, Arkansas, a 'well-dressed and presentable young man' was hitching lifts despite laws against such activity. When safely aboard, he would confide details of the forthcoming Second Coming of Christ to his startled host(s). After revealing his insights, he would vanish from the moving car. The 'presentable young man' continued his excursions for over a year. The last reported sighting took place on 6 July 1980, when the vanishing hitchhiker's prophecy was apparently a bungled kind of meteorology. He assured his worried driver (and passengers, thus making this a multiple sighting) that it would 'never rain again' - before vanishing from the speeding car a moment or two later. A named Arkansas State Trooper - Robert Rotten - later confirmed to the press (Indiana Star, 26 July 1980) that they had logged two reports of this character's behaviour, but were unofficially aware of many more.

- At around the same time as the above prophetic hitchhiker, a second itinerant soothsayer was vanishing from cars around Interstate 5, between Tacoma, Washington, and Eugene, Oregon. Described as a 50-60 year old woman, sometimes in a nun's habit, the hitchhiker would discourse on God and Salvation before vanishing from the car's cabin. Another witness had been warned to repent his (unspecified) sins, or die in a road accident. As 1980 progressed, this vanishing hitchhiker began to display a worrying interest in Mount St. Helens. She took to warning motorists that the eruption of that volcano in May 1980 signified God's warning to the Northwest and that those who did not return to the fold could expect to perish volcanically in the very near future (18 May, to be precise). Tacoma police logged twenty calls from motorists who had met this sinister individual. Latterly, the woman took on a new guise (or perhaps a new vanishing hitchhiker with similar preoccupations assumed her duties) and the roads were again busy with whispered intimations of pending disaster (this time, set for 12 October). The Midnight Globe (5 August 1980) quotes two police officers who had dealt with shocked motorists and one motorist who claimed to have met the vanishing woman or women.

Cultural references[편집]

- In 1941, the Orson Welles Show presented the debut broadcast of Lucille Fletcher's The Hitch-Hiker, starring Orson Welles. The play contained a variation or subversion of the myth where it is the driver that is the ghost, and a hitchhiker (but not the title character) that is alive. A man (or woman in subsequent adaptations) is involved in a car crash that initially appears to have been a minor blown tire. "The Hitch-Hiker", an episode of The Twilight Zone, and the episode "RoadKill" of the TV series Supernatural, were notable television adaptations of this particular variation.

- The vanishing hitchhiker was the inspiration for Dickey Lee's recording on a 45 rpm single (TCF-102) of the song "Laurie", which is subtitled "Strange Things Happen ..." Country Joe McDonald wrote and performed a song about a vanishing hitchhiker called "Hold On It's Coming", later covered by New Riders of the Purple Sage. Other modern songs include "I Guess It Doesn't Matter Anymore" by Blackmore's Night on Village Lanterne and "Bringing Mary Home" by the Country Gentlemen originally on Starday's subsidiary, Nashville Records 45 rpm # 2018 in 1964.

- Author Alvin Schwartz includes a variation of the vanishing hitchhiker legend in his book More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark along with copious notes detailing the origin and variations of the story.

- David Allan Coe's song "The Ride" reverses the vanishing hitchhiker scenario. In "The Ride", Coe is the pedestrian hitching a ride in a Cadillac driven by Hank Williams from Montgomery, Alabama (Williams' hometown) to Nashville, Tennessee. At the end of the ride, Williams turns the car around, stops, and lets Coe out, saying "This is where you get off, boy, 'cause I'm goin' back to Alabam'."

- Keith Bryant's version of "The Ride" is about an amateur Nascar driver that gets a ride to Daytona International Speedway from Dale Earnhardt.

- "Phantom 309" depicts Red Sovine thumbing a ride with a trucker. When the driver lets Sovine out a nearby truck stop, he tells him to inform the truck stop crowd of who sent him. Silence overtakes the truck stop before one of the patrons tells Sovine the story of the driver, who died after crashing his rig to spare a group of teenagers he hadn't seen in time to stop after topping a hill. Sovine also recorded "Bringing Mary Home", in which he picks up a young woman standing by the road on a stormy night, only to have her disappear before he reaches the address she gives him. Her mother answers the door and tells him that he is the thirteenth man who has come to her, bringing Mary home.

- "Big Joe and Phantom 309" written by Tommy Faile and sung by Tom Waits in his 1975 album Nighthawks at the Diner.

- Hilton Edwards directed a 1951 movie called Return to Glennascaul, starring Orson Welles, which centered around a Vanishing Hitchhiker event.

- In the Girl on the Road episode of the obscure TV series The Veil hosted by Boris Karloff, a motorist aids a girl stranded on the highway. After she vanishes, he searches for her, eventually discovering she had died years before in a wreck on the stretch of road where he met her.

- In the 1960 British horror film The City of the Dead (aka Horror Hotel), actor Valentine Dyall plays a centuries-old warlock who hitches a ride with two different characters in the movie and then vanishes from the car as soon as they reach an ancient New England witch village.

- The Swirling Eddies released a song on their Outdoor Elvis album (1990) called "Urban Legends". In the lyrics, the narrator critiques the naive belief in urban legends by satirically having the vanishing hitchhiker tell the car driver to "stop telling lies" before he vanishes.

- Dust Devil a 1993 cult film by Richard Stanley set in South Africa was, according to the DVD commentary, inspired by the director's memory of being told the Vanishing Hitchhiker legend as a youngster.

- The 1985 film Pee-wee's Big Adventure includes a scene that is a variation on "Phantom 309". While hitchhiking across the country in search of his stolen bicycle, Pee Wee (Paul Reubens) thumbs a ride with a female truck driver named "Large Marge" who relates to him the story of "the worst accident I ever seen," which concludes with Marge's face contorting very ghoulishly. When Pee Wee announces to the truck stop that Large Marge sent him, one customer recounts that this particular evening is the anniversary of said accident. It is also explained that this accident happened to Large Marge herself.

- The contemporary folk-style song "Ferryman" by Mercedes Lackey and Leslie Fish offers another version of the reversal. The encounter here is between a young girl seeking to cross a river in a violent storm, and a ferryman who agrees to take her without charge. Although the tone implies an unworldly nature to the girl, in the end it is the ferryman who is revealed as the ghost. This version includes a garment as a token: the girl’s shawl, left as a pledge for the fare, is found in the morning on the ferryman’s grave.

- A popular Bollywood horror film of the 1960s Woh Kaun Thi? meaning "Who was she?", has the sequence where the leading man gives a lift to a beautiful woman on a stormy night. Her manner is mysterious and answers questions vaguely and she asks to be dropped off at a gate. He says "But that's a cemetery!". She looks at him, smiles enigmatically and gets off the car and walks into the cemetery. The gate opens automatically for her.

- The website SCP Foundation has an entry on a vanishing hitchhiker, a woman who was ritualistically murdered, and has anyone who picks her up stop at the cemetery where she was buried, where she will vanish. The hitchhiker would leave her sweater behind, and if the motorist who picked her up touched it, they would be compelled to bring it to her elderly parents. In an attempt to vanquish the spirit, a researcher had her parents killed and their home destroyed, reasoning that if the hitchhiker had nothing to come back to, she would stop appearing. This caused the hitchhiker to become homicidal, and begin appearing as a mutilated corpse.

- the game collection Shiver has a game called "the Vanishing Hitchhiker".

- Disney (or at least those who work for his studios) seems to have a feel for this theme, as at the end of the Haunted Mansion ride, the ghostly guide gives the final warning to the riders "beware of hitchhiking ghosts" before revealing the ghostly reflections of the three ghosts, notably the same ones showing the hitchhikers thumb earlier, attempting to ride on the passenger carts and enjoying the efforts. Some who experience the ride may or may not believe at least one of them successfully escaped the mansion, for the moment. Another of the Disney examples was in the animated sequel "Atlantis: Milo's Return" in which the team, driving through the North American desserts, pick up a man named Shacashi... after passing by someone of his likeness at least three times. Shacashi said all Native Americans look alike to outsiders to make such a detail seem normal, but eventually, as a coyote attack took place in the form of a sandstorm, he told them with glowing red eyes that a form of evil is taking place that he needs help with, then disappears while the vehicle was still moving just before it crashed. Everyone survived, but they made an agreement to avoid picking up any more hitchhikers before investigating the message they were given further. While investigating, it was discovered Shacashi is the name of a tribal wind-spirit, (or at least a ghost called as such, but the same principle either way).

See also[편집]

- Haunted road

- Belchen Tunnel (The "white woman" of the Belchen Tunnel, Switzerland)

- Resurrection Mary

- John Keel

- Highway hypnosis

- Curse

- The Hitcher (1986 film)

- The Hitch-Hiker (1953 film)

- Shipley Hollow Road

- Niles Canyon ghost

- White Rock Lake

References[편집]

- ↑ Schmetzke, Angelika. (1988). The Evidence for Phantom Hitch-Hikers by Michael Goss. Folklore, Vol. 99, No. 2. p. 265

- ↑ Wechner, Bernd "Hitch-hiking in the Bible". Retrieved on 2009-12-30.

Books[편집]

- Bielski, Ursula, (1997) "Road Tripping" from Chicago Haunts: Ghostlore of the Windy City (Chicago: Lake Claremont Press, 1997).

- Brunvand, Jan Harold, (1981), The Vanishing Hitchhiker (ISBN 0-393-95169-3)

- Goss, Michael, (1984), The Evidence for Phantom Hitch-hikers (ISBN 0-85030-376-1)

External links[편집]

[|thumb|An anonymous graffito of the Slender Man, drawn on a road in Raleigh, North Carolina.]]

The Slender Man (also known as Slenderman) is a fictional character that originated as an Internet meme created by Something Awful forums user Victor Surge in 2009. It is depicted as resembling a thin, unnaturally tall man with a blank and usually featureless face, and wearing a black suit. The Slender Man is commonly said to stalk, abduct, or traumatize people, particularly children.[1] The Slender Man is not tied to any particular story, but appears in many disparate works of fiction, mostly composed online.[2]

Origin[편집]

The Slender Man was created on a thread in the Something Awful forum on June 8, 2009, with the goal of editing photographs to contain supernatural entities. On June 10, a forum poster with the user name "Victor Surge" contributed two black and white images of groups of children, to which he added a tall, thin spectral figure wearing a black suit.[3][4] Previous entries had consisted solely of photographs; however, Surge supplemented his submission with snatches of text, supposedly from witnesses, describing the abductions of the groups of children, and giving the character the name, "The Slender Man":

We didn’t want to go, we didn’t want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time…

1983, photographer unknown, presumed dead.

One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen children vanished and for what is referred to as “The Slender Man”. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.

1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.[4]

These additions effectively transformed the photographs into a work of fiction. Subsequent posters expanded upon the character, adding their own visual or textual contributions.[3][4]

Description[편집]

The Slender Man is described as very tall and thin with unnaturally long, tentacle-like arms (or merely tentacles),[2] which it can extend to intimidate or capture prey. It has a white, featureless head and appears to be wearing a dark suit and tie. The Slender Man is associated with the forest and has the ability to teleport.[5][6]

Development[편집]

The Slender Man soon went viral, spawning numerous works of fanart, cosplay and online fiction known as "creepypasta": scary stories told in short snatches of easily copyable text that spread from site to site. Divorced from its original creator, the Slender Man became the subject of myriad stories by multiple authors within an overarching mythos.[2]

The first video series involving the Slender Man evolved from a post on the Something Awful thread by user "ce gars". It tells of a fictional film school friend named Alex Kralie, who had stumbled upon something troubling while shooting his first feature-length project, Marble Hornets. The video series, published in found footage style on YouTube, forms an alternate reality game describing the filmers' fictional experiences with the Slender Man. The ARG also incorporates a Twitter feed and an alternate YouTube channel created by a user named "totheark".[1][7] Marble Hornets is now one of the most popular Slender Man creations, with over 250,000 followers around the world, and 55 million views.[8] Other Slender Man-themed YouTube serials followed, including EverymanHYBRID and Tribe Twelve.[1]

In 2011, Markus "Notch" Persson, creator of the sandbox indie game Minecraft, added a new hostile mob to the game, which he named the "Enderman" when multiple users on Reddit and Google+ commented on the similarity to the Slender Man.[9] In 2012, the Slender Man was adapted into a video game titled Slender: The Eight Pages; as of August, 2012, the game has been downloaded over 2 million times.[10] Several popular variants of the game followed, including Slenderman's Shadow[11] and Slender Man for iOS, which became the second most-popular app download.[12] The sequel to Slender: The Eight Pages, Slender: The Arrival, was released in 2013.[13] Several independent films about the Slender Man have been released or are in development, including Entity[14] and The Slender Man, released free online after a $10,000 Kickstarter campaign.[15] In 2013, it was announced that Marble Hornets would become a theatrical film.[8]

Reaction[편집]

Aleks Krotoski, a commentator for BBC Radio 4, called the Slender Man "the first great myth of the web".[5] The success of the Slender Man "legend" has been ascribed to the chaotic, ambiguous nature of the Internet. While nearly everyone involved understands on some level that the Slender Man is not real, the Internet offers up a mess of conflicting perspectives, blurring the boundary between fiction and reality and obscuring the character's origin, thus lending it an air of authenticity.[4] Victor Surge (real name Eric Knudsen)[16] has commented that many people, despite understanding that the Slender Man was created on the Something Awful forums, still entertain the possibility that it might be real.[5]

Professor Tom Peddit of the University of Southern Denmark has described the Slender Man as being an exemplar of the modern age's closing of the "Gutenberg Parenthesis"; the time period from the invention of the printing press to the spread of the web in which stories and information were codified in discrete media, to a return to the older, more primal forms of storytelling, exemplified by oral tradition and campfire tales, in which the same story can be retold, reinterpreted and recast by different tellers, expanding and evolving with time.[5]

Professor Shira Chess of the University of Georgia has noted that the Slender Man exemplifies the similarities between traditional folklore and the open source ethos of the Internet, and that, unlike those of traditional monsters such as vampires and werewolves, the Slender Man's mythos can be tracked and signposted, giving a powerful insight into how myth and folklore form.[3] Tye Van Horn, a writer for The Elm, has suggested that the Slender Man represents modern fear of the unknown; in an age flooded with information people have become so inured to ignorance that they now fear what they cannot understand.[17] Troy Wagner, the creator of Marble Hornets, ascribes the terror of the Slender Man to its malleability; people can shape it into whatever frightens them most.[5]

Copyright[편집]

Despite his legendary qualities, the Slender Man is not in the public domain. Several profit-making ventures involving him have unequivocally acknowledged the user Eric "Victor Surge" Knudsen as the creator of this fictional character, and several more have been legally blocked from distribution (including the Kickstarter-funded film) after legal complaints from various sources. Though Knudsen himself has given his personal blessing to a number of Slender Man-related projects, it is complicated by the fact that, while he is the character's creator, a third party holds the options to any adaptations into other media, including film and television. The identity of this option holder has not been made public.[16]

See also[편집]

References[편집]

- ↑ 가 나 다 Gail Arlene De Vos (2012). 《What Happens Next?》. ABC-CLIO. 162쪽. ISBN 9781598846348.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Aja Romano (2012). “The definitive guide to creepypasta—the Internet’s urban legends”. Daily Dot. 2013년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Shira Chess (2012). “Open-Sourcing Horror: The Slender Man, Marble Hornets, and genre negotiations”. 《Information, Communication & Society》 15 (3): 374–393. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.642889.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Patrick Dane (2013). “Why Slenderman Works: The Internet Meme That Proves Our Need To Believe”. whatculture.com. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 “Digital Human: Tales”. bbc.co.uk. 2012. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kristin Tillotsin (2011). “Tall, skinny, scary—and all in your head”. startribune.com. 2013년 2월 23일에 확인함.

- ↑ Peters, Lucia (2011년 5월 14일). “Creepy Things That Seem Real But Aren’t: The Marble Hornets Project”. Crushable. 2012년 10월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Dave McNary (2013). “'Marble Hornets' flying to bigscreen”. Variety. 2013년 2월 26일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Notch reveals new mob, dubs them Endermen in reference to Slender Man.”. igx.com. 2011. 2013년 2월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gary Marston (2012). “Slender review”. explosion.com. 2013년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lana Polansky (2012년 8월 20일). “Slenderman’s Shadow "Sanatorium" Map Released”. Gameranx. 2012년 9월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Tom Senior (2012년 7월 26일). “Slender Man Source mod will let you scare the hell out of yourself for free, with friends”. PC Gamer. 2012년 9월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Jeffrey Matulef (2013년 2월 11일). “Pre-orders for Slender: The Arrival are half-off, come with instant beta access”. Eurogamer. 2013년 4월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “First Trailer & Poster For The Jadallah Brothers’ Horror Movie ENTITY!”. FilmoFilia. 2013. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Slender Man Movie Producer Steven Belcher Wants to Create True Terror with the Faceless Figure”. GameTrailers. 2013. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Miles Klee (2013). “How the Internet's creepiest meme mutated from thought experiment to Hollywood blockbuster”. The Daily Dot. 2013년 11월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ Tye Van Horn (2013). “Behind You: The Cultural Relevance of Slender Man”. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

External links[편집]

The Slender Man (also known as Slenderman) is a fictional character that originated as an Internet meme created by Something Awful forums user Victor Surge in 2009. It is depicted as resembling a thin, unnaturally tall man with a blank and usually featureless face, and wearing a black suit. The Slender Man is commonly said to stalk, abduct, or traumatize people, particularly children.[1] The Slender Man is not tied to any particular story, but appears in many disparate works of fiction, mostly composed online.[2]

Origin[편집]

The Slender Man was created on a thread in the Something Awful forum on June 8, 2009, with the goal of editing photographs to contain supernatural entities. On June 10, a forum poster with the user name "Victor Surge" contributed two black and white images of groups of children, to which he added a tall, thin spectral figure wearing a black suit.[3][4] Previous entries had consisted solely of photographs; however, Surge supplemented his submission with snatches of text, supposedly from witnesses, describing the abductions of the groups of children, and giving the character the name, "The Slender Man":

We didn’t want to go, we didn’t want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time…

1983, photographer unknown, presumed dead.

One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen children vanished and for what is referred to as “The Slender Man”. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.

1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.[4]

These additions effectively transformed the photographs into a work of fiction. Subsequent posters expanded upon the character, adding their own visual or textual contributions.[3][4]

Description[편집]

The Slender Man is described as very tall and thin with unnaturally long, tentacle-like arms (or merely tentacles),[2] which it can extend to intimidate or capture prey. It has a white, featureless head and appears to be wearing a dark suit and tie. The Slender Man is associated with the forest and has the ability to teleport.[5][6]

Development[편집]

The Slender Man soon went viral, spawning numerous works of fanart, cosplay and online fiction known as "creepypasta": scary stories told in short snatches of easily copyable text that spread from site to site. Divorced from its original creator, the Slender Man became the subject of myriad stories by multiple authors within an overarching mythos.[2]

The first video series involving the Slender Man evolved from a post on the Something Awful thread by user "ce gars". It tells of a fictional film school friend named Alex Kralie, who had stumbled upon something troubling while shooting his first feature-length project, Marble Hornets. The video series, published in found footage style on YouTube, forms an alternate reality game describing the filmers' fictional experiences with the Slender Man. The ARG also incorporates a Twitter feed and an alternate YouTube channel created by a user named "totheark".[1][7] Marble Hornets is now one of the most popular Slender Man creations, with over 250,000 followers around the world, and 55 million views.[8] Other Slender Man-themed YouTube serials followed, including EverymanHYBRID and Tribe Twelve.[1]

In 2011, Markus "Notch" Persson, creator of the sandbox indie game Minecraft, added a new hostile mob to the game, which he named the "Enderman" when multiple users on Reddit and Google+ commented on the similarity to the Slender Man.[9] In 2012, the Slender Man was adapted into a video game titled Slender: The Eight Pages; as of August, 2012, the game has been downloaded over 2 million times.[10] Several popular variants of the game followed, including Slenderman's Shadow[11] and Slender Man for iOS, which became the second most-popular app download.[12] The sequel to Slender: The Eight Pages, Slender: The Arrival, was released in 2013.[13] Several independent films about the Slender Man have been released or are in development, including Entity[14] and The Slender Man, released free online after a $10,000 Kickstarter campaign.[15] In 2013, it was announced that Marble Hornets would become a theatrical film.[8]

Reaction[편집]

Aleks Krotoski, a commentator for BBC Radio 4, called the Slender Man "the first great myth of the web".[5] The success of the Slender Man "legend" has been ascribed to the chaotic, ambiguous nature of the Internet. While nearly everyone involved understands on some level that the Slender Man is not real, the Internet offers up a mess of conflicting perspectives, blurring the boundary between fiction and reality and obscuring the character's origin, thus lending it an air of authenticity.[4] Victor Surge (real name Eric Knudsen)[16] has commented that many people, despite understanding that the Slender Man was created on the Something Awful forums, still entertain the possibility that it might be real.[5]

Professor Tom Peddit of the University of Southern Denmark has described the Slender Man as being an exemplar of the modern age's closing of the "Gutenberg Parenthesis"; the time period from the invention of the printing press to the spread of the web in which stories and information were codified in discrete media, to a return to the older, more primal forms of storytelling, exemplified by oral tradition and campfire tales, in which the same story can be retold, reinterpreted and recast by different tellers, expanding and evolving with time.[5]

Professor Shira Chess of the University of Georgia has noted that the Slender Man exemplifies the similarities between traditional folklore and the open source ethos of the Internet, and that, unlike those of traditional monsters such as vampires and werewolves, the Slender Man's mythos can be tracked and signposted, giving a powerful insight into how myth and folklore form.[3] Tye Van Horn, a writer for The Elm, has suggested that the Slender Man represents modern fear of the unknown; in an age flooded with information people have become so inured to ignorance that they now fear what they cannot understand.[17] Troy Wagner, the creator of Marble Hornets, ascribes the terror of the Slender Man to its malleability; people can shape it into whatever frightens them most.[5]

Copyright[편집]

Despite his legendary qualities, the Slender Man is not in the public domain. Several profit-making ventures involving him have unequivocally acknowledged the user Eric "Victor Surge" Knudsen as the creator of this fictional character, and several more have been legally blocked from distribution (including the Kickstarter-funded film) after legal complaints from various sources. Though Knudsen himself has given his personal blessing to a number of Slender Man-related projects, it is complicated by the fact that, while he is the character's creator, a third party holds the options to any adaptations into other media, including film and television. The identity of this option holder has not been made public.[16]

See also[편집]

References[편집]

- ↑ 가 나 다 Gail Arlene De Vos (2012). 《What Happens Next?》. ABC-CLIO. 162쪽. ISBN 9781598846348.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Aja Romano (2012). “The definitive guide to creepypasta—the Internet’s urban legends”. Daily Dot. 2013년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Shira Chess (2012). “Open-Sourcing Horror: The Slender Man, Marble Hornets, and genre negotiations”. 《Information, Communication & Society》 15 (3): 374–393. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.642889.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Patrick Dane (2013). “Why Slenderman Works: The Internet Meme That Proves Our Need To Believe”. whatculture.com. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 “Digital Human: Tales”. bbc.co.uk. 2012. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ Kristin Tillotsin (2011). “Tall, skinny, scary—and all in your head”. startribune.com. 2013년 2월 23일에 확인함.

- ↑ Peters, Lucia (2011년 5월 14일). “Creepy Things That Seem Real But Aren’t: The Marble Hornets Project”. Crushable. 2012년 10월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Dave McNary (2013). “'Marble Hornets' flying to bigscreen”. Variety. 2013년 2월 26일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Notch reveals new mob, dubs them Endermen in reference to Slender Man.”. igx.com. 2011. 2013년 2월 21일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gary Marston (2012). “Slender review”. explosion.com. 2013년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lana Polansky (2012년 8월 20일). “Slenderman’s Shadow "Sanatorium" Map Released”. Gameranx. 2012년 9월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Tom Senior (2012년 7월 26일). “Slender Man Source mod will let you scare the hell out of yourself for free, with friends”. PC Gamer. 2012년 9월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Jeffrey Matulef (2013년 2월 11일). “Pre-orders for Slender: The Arrival are half-off, come with instant beta access”. Eurogamer. 2013년 4월 3일에 확인함.

- ↑ “First Trailer & Poster For The Jadallah Brothers’ Horror Movie ENTITY!”. FilmoFilia. 2013. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Slender Man Movie Producer Steven Belcher Wants to Create True Terror with the Faceless Figure”. GameTrailers. 2013. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Miles Klee (2013). “How the Internet's creepiest meme mutated from thought experiment to Hollywood blockbuster”. The Daily Dot. 2013년 11월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ Tye Van Horn (2013). “Behind You: The Cultural Relevance of Slender Man”. 2013년 2월 20일에 확인함.

External links[편집]

데비존스의 함[편집]

데비 존스의 함(혹은 데비 존스의 락커, 영어:Davy Jones' Locker 또는 Davy Jones's Locker)는 관용어로 난파선이나 선원이 죽으면서 해저 바닥으로 가라앉아 가는 가상의 공간이다.[2] 이는 해상에서의 죽음을 완곡어법으로 표현한 것인데 영미권에서는 일반적으로 배가 난파되거나 혹은 이로 인해 선원이 익사하면 데비 존스의 함으로 보내졌다.라고 한다(영어:sent to Davy Jones' Locker).[3]

데비 존스라는 이름의 기원은 악마 The origins of the name of Davy Jones, the sailor's devil,[2] are unclear, with a 19th-century dictionary tracing Davy Jones to a "ghost of Jonah".[4] Other explanations of this nautical superstition have been put forth, including an incompetent sailor or a pub owner who kidnapped sailors.

History[편집]

The earliest known reference of the negative connotation of Davy Jones occurs in the Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts, by the author Daniel Defoe, published in 1726 in London.

Some of Loe's Company said, They would look out some things, and give me along with me when I was going away; but Ruffel told them, they should not, for he would toss them all into Davy Jones's Locker if they did.

— Daniel Defoe[5]

An early description of Davy Jones occurs in Tobias Smollett's The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle, published in 1751:[4]

This same Davy Jones, according to sailors, is the fiend that presides over all the evil spirits of the deep, and is often seen in various shapes, perching among the rigging on the eve of hurricanes:, ship-wrecks, and other disasters to which sea-faring life is exposed, warning the devoted wretch of death and woe.

— Tobias Smollett[4]

In the story Jones is described as having saucer eyes, three rows of teeth, horns, a tail, and blue smoke coming from his nostrils.

Proposed origins of the tale[편집]

The origin of the tale of "Davy Jones" is unclear, and many conjectural[2] or folklore[6] explanations have been proposed:

- The 1898 Dictionary of Phrase and Fable connects Dave to the West Indian duppy (duffy) and Jones to biblical Jonah:

He’s gone to Davy Jones’s locker, i.e. he is dead. Jones is a corruption of Jonah, the prophet, who was thrown into the sea. Locker, in seaman’s phrase, means any receptacle for private stores; and duffy is a ghost or spirit among the West Indian negroes. So the whole phrase is, "He is gone to the place of safe keeping, where duffy Jonah was sent to."

— E. Cobham Brewer[4]

- David Jones, a real pirate, although not a very well-known one, living on the Indian Ocean in the 1630s.[7]

- Duffer Jones, a notoriously myopic sailor who often found himself over-board.[8]

- A British pub owner who supposedly threw drunken sailors into his ale locker and then gave them to be drafted on any ship.[6] He may be the pub owner who is referenced in the 1594 song "Jones's Ale is Newe."[출처 필요]

Reputation[편집]

The tale of Davy Jones causes fear among sailors, who may refuse to discuss Davy Jones in any great detail.[출처 필요] Not all traditions dealing with Davy Jones are fearful. In traditions associated with sailors crossing the Equatorial line, there was a "raucous and rowdy" initiation presided over by those who had crossed the line before, known as shellbacks, or Sons of Neptune. The eldest shellback was called King Neptune, and Davy Jones would be re-enacted as his first assistant.[9]

Use in media[편집]

19th century[편집]

In 1824 Washington Irving mentions Jones' name in his Adventures of the Black Fisherman:

He came, said he, in a storm, and he went in a storm; he came in the night, and he went in the night; he came nobody knows whence, and he has gone nobody knows where. For aught I know he has gone to sea once more on his chest, and may land to bother some people on the other side of the world; though it is a thousand pities, added he, if he has gone to Davy Jones's locker.

In Edgar Allan Poe's "King Pest" of 1835, Davy Jones is referred to dismissively by the anti-hero, Tarpaulin, when King Pest refers to "that unearthly sovereign" "whose name is Death." Tarpaulin responds, "Whose name is Davy Jones!"[11]

Herman Melville mentions Jones in the 1851 classic Moby-Dick:

There was young Nat Swaine, once the bravest boat-header out of all Nantucket and the Vineyard; he joined the meeting, and never came to good. He got so frightened about his plaguy soul, that he shrinked and sheered away from the whales, for fear of after-claps, in case he got stove and went to Davy Jones.

In Charles Dickens's Bleak House (1852–3), the character Mrs. Badger quotes her former husband's work ethic, portraying Davy Jones in a formidable light:

"It was a maxim of Captain Swosser's", said Mrs. Badger, "speaking in his figurative naval manner, that when you make pitch hot, you cannot make it too hot; and that if you only have to swab a plank, you should swab it as if Davy Jones were after you."

In Robert Louis Stevenson's 1883 novel Treasure Island, Davy Jones appears three times, for example in the phrase “in the name of Davy Jones”.[14][15]

20th century[편집]

In J. M. Barrie's 1904 play and 1911 novel Peter and Wendy, Captain Hook sings a song:

Yo ho, yo ho, the pirate life,

The flag o' skull and bones,

A merry hour, a hempen rope,

And hey for Davy Jones.— J. M. Barrie, [16]

A current US Navy song "Anchors Aweigh" refers to Davy Jones in its current lyrics adopted in the 1920s:

Stand, Navy, out to sea, Fight our battle cry;

We'll never change our course, So vicious foe

steer shy-y-y-y.

Roll out the TNT, Anchors Aweigh.

Sail on to victory

And sink their bones to Davy Jones, hooray!

Anchors Aweigh, my boys, Anchors Aweigh.

Farewell to foreign shores, we sail at break of day-ay-ay-ay.

Through our last night on shore, drink to the foam,

Until we meet once more,

Here's wishing you a happy voyage home.— [17]

Late 20th century songs that refer to Davy Jones include Paul McCartney's song Morse Moose and the Grey Goose and the Beastie Boys' song Rhymin and Stealin.

In The Adventures of Tintin, the character Captain Haddock makes occasional reference to Davy Jones. Also in Secret of the Unicorn on page 17 while recounting Sir Francis Haddock manuscript to Tintin, references pirate ship raising the red flag and says, "The red pennant!... No quarter given!... A fight to the death, no prisoners taken! You understand? If we're beaten, then it's every man to Davy Jones's locker!"

In the Genesis song Dodo/Lurker [Abacab album 1981] the sixth stanza has the lyrics: "One he got a dream of love, deep as the ocean Where does he go, what does he do? Will the siren team with Davy Jones, And trap him at the bottom of the sea? "

The Iron Maiden song, "Run Silent Run Deep" (about submarine warfare) contains the lines: "The lifeboats shattered, the hull is torn/The tar black smell of burning oil/On the way down to Davy Jones/Every man for himself – you're on your own..."

The band Clutch have a song entitled Big News I, which says, when played backwards, "them bones, them bones, them dry, dry bones/ Come down to the locker of Davy Jones".[18]

In the 1960s television series The Monkees episode "Hitting The High Seas" the character Davy Jones (played by musician Davy Jones) receives special treatment while kidnapped in a ship as he claims to be related to "The Original" Davy Jones, his grandfather. Meanwhile, his fellow bandmembers are held hostage, leading to various humorous situations.

In the 1994 movie The Pagemaster, Adventure (Patrick Stewart) and Richard Tyler (Macaulay Culkin) are shipwrecked and when Richard Tyler asks what happened to Fantasy and Horror, Adventure sadly replies,"I'm afraid they've gone below to Davey Jones."

21st century[편집]

The concept of Davy Jones was conflated with the legend of the Flying Dutchman in the Pirates of the Caribbean film series, in which Davy Jones's locker is portrayed as a sort of purgatory, with Davy Jones being a captain assigned to ferry those drowned at sea to the afterlife before he corrupted his purpose out of anger at his betrayal by his lover, the sea goddess Calypso.

In the video game Banjo-Tooie, on the Jolly Roger's Lagoon level the player can swim to the bottom of the lagoon and find a giant locker with the name "D. Jones" on it. Destroying the locker will open a path to the level boss.

The term has also been used repeatedly in the animated TV series SpongeBob SquarePants to represent an actual locker in the bottom of the sea where Davy Jones (of The Monkees fame) keeps his gym socks.[19]

Adam Carolla has repeatedly used or referenced the term on his daily podcast, The Adam Carolla Show.

The Devil Makes Three references the idiom on their single "The Plank".

In his novel The Last Dickens, Matthew Pearl makes the Captain of the Samaria transatlantic liner assume that Herman the Parsee might be sleeping soundly in Davy Jones's locker, namely that he has almost certainly perished in the depths. Use of seamen jargon chimes with the dickensian topic and environment of the novel.

See also[편집]

Notes[편집]

- ↑ Caption: Oh learn a lesson from Joe Gotch - Without a lifebelt he stood watch - "Abandon ship" came over the phones - He now resides with Davey Jones

References[편집]

- ↑ However, presented here character is a fake, created by Pipes, Perry and Pickle to scare Mr. Trunnion; see: Smollett, Tobias (1751). 《The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle》. London: D. Wilson. 66쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Farmer, John S; Henley, William Ernest (1927). 《A Dictionary of slang and Colloquial English》. 128–129쪽.

- ↑ Farmer, John Stephen; Henley, W. E. (1891). 《Slang and its analogues past and present: A dictionary ... with synonyms in English, French ... etc.》. Harrison & Sons. 258쪽. 2013년 1월 16일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Brewer, E. Cobham (1898년 1월 1일). “Davy Jones’s Locker.”. 《Dictionary of Phrase and Fable》. 2006년 4월 30일에 확인함.

- ↑ Defoe, Daniel (1726). 《The four years voyages of capt. George Roberts. Written by himself》. 89쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 Michael Quinion (1999). “World Wide Words”. 2013년 1월 15일에 확인함.

- ↑ Rogoziński, Jan (1997년 1월 1일). 《The Wordsworth Dictionary of Pirates》. Hertfordshire. ISBN 1-85326-384-2.

- ↑ Shay, Frank. 《A Sailor's Treasury》. Norton. ASIN B0007DNHZ0.

- ↑ Connell, Royal W; Mack, William P (2004년 8월 1일). 《Naval Ceremonies, Customs, and Traditions》. 76–79쪽. ISBN 9781557503305.

- ↑ Irving, Washington. “Adventure of the Black Fisherman”. Free Online Library. 2010년 3월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ Poe, Edgar Allan (1835) "s:King Pest"

- ↑ Melville, Herman (1851) s:Moby-Dick/Chapter 18

- ↑ The Oxford Illustrated Dickens, page 229.

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1883) s:Treasure Island/Chapter 22

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1883) s:Treasure Island/Chapter 20

- ↑ Barrie, J. M. (1904 and 1911) s:Peter and Wendy/Chapter 15

- ↑ “Clutch Lyrics”. 2013년 2월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Davy Jones' Locker”. 2010년 3월 17일에 확인함.

| 설총/연습장 | |||||||||||||||||

| 중국어 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 정체자 | 太極圖 | ||||||||||||||||

| 간체자 | 太极图 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| 한국어 | |||||||||||||||||

| 한글 | 태극도 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

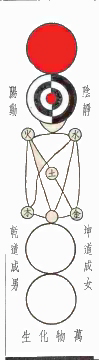

Taijitu (Traditional Chinese: 太極圖; Simplified Chinese: 太极图; Pinyin: tàijítú; Wade-Giles: t'ai⁴chi²t'u²; rough English translation: “diagram of supreme ultimate”) is a term which refers to a Chinese symbol for the concept of yin and yang (Taiji). It is the universal symbol of the religion known as Taoism and is also often used by non-Taoists to represent the concept of opposites existing in harmony. The taijitu consists of a rotated pattern inside a circle. One common pattern has an S-shaped line that divides the circle into two equal parts of different colors. The pattern may have one or more large dots. The classic Daoist taijitu (pictured right), for example, is black and white with a black dot upon the white background, and a white dot upon the black background.

Patterns similar to the taijitu also form part of Celtic, Etruscan, Roman and much earlier Cucuteni-Trypillian culture iconography, where they are loosely referred to as yin yang symbols by modern scholars.[1][2][3] A Roman shield pattern from around 430 AD is identical to the taijitu except in color. However no relationship between these and the Chinese symbol has been established.

Geometric figure[편집]

The taijitu is a simple geometric figure, consisting of variations of nested circles. The classical Taoist symbol can be drawn with the help of a compass and straightedge: one draws on the diameter of a circle two non-overlapping circles each of which has a diameter equal to the radius of the outer circle. One keeps the line that forms an "S," and one erases or obscures the other line.[4] Thus, one obtains a form which Taoist texts liken to a pair of fishes nestling head to tail against each other.[5] This basic pattern is not a pure product of human imagination, but also occurs − of less geometrical precision − in nature (see image at the right). In the most common Daoist variant, the two differently colored halves additionally contain one dot each of opposite color.[5]

Taoist symbolism[편집]

The term taijitu (literally "diagram of the supreme ultimate") is, in modern times, commonly used to mean the simple "divided circle" form (![]() ), but it may refer to any of several schematic diagrams that contain at least one circle with an inner pattern of symmetry representing yin and yang — for example, the one at right, which was Zhou Dunyi's (1017–1073) original form of the diagram.[6] It was later popularized further in China by Ming period author Lai Zhide (1525–1604).

), but it may refer to any of several schematic diagrams that contain at least one circle with an inner pattern of symmetry representing yin and yang — for example, the one at right, which was Zhou Dunyi's (1017–1073) original form of the diagram.[6] It was later popularized further in China by Ming period author Lai Zhide (1525–1604).

In the taijitu, the circle itself represents a whole (see wuji), while the black and white areas within it represent interacting parts or manifestations of the whole. The white area represents yang elements, and is generally depicted as rising on the left, while the dark (yin) area is shown descending on the right (though other arrangements exist, most notably the version used on the flag of South Korea). The image is designed to give the appearance of movement. Each area also contains a large dot of a differing color at its fullest point (near the zenith and nadir of the figure) to indicate how each will transform into the other.

The Taijitu symbol is an important symbol in martial arts, particularly t'ai chi ch'uan (Taijiquan),[7] and Jeet Kune Do. In this context, it is generally used to represent the interplay between hard and soft techniques.

Taijitu shuo[편집]

The Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) wrote the Taijitu shuo 太極圖說 "Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate", which became the cornerstone of Neo-Confucianist cosmology. His brief text synthesized aspects of Chinese Buddhism and Taoism with metaphysical discussions in the Yijing.

Zhou's key terms Wuji and Taiji appear in the opening line 無極而太極, which Adler notes could also be translated "The Supreme Polarity that is Non-Polar".

Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)! The Supreme Polarity in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established. The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.[8]

Instead of usual Taiji translations "Supreme Ultimate" or "Supreme Pole", Adler uses "Supreme Polarity" (see Robinet 1990) because Zhu Xi describes it as the alternating principle of yin and yang, and ...

insists that taiji is not a thing (hence "Supreme Pole" will not do). Thus, for both Zhou and Zhu, taiji is the yin-yang principle of bipolarity, which is the most fundamental ordering principle, the cosmic "first principle." Wuji as "non-polar" follows from this.

European iconography[편집]

Cucuteni-Trypilian culture[편집]

Symbols looking like taiji were found on numerous artifacts from Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. [9][10]

Celts[편집]

In Celtic art, the motif of two interlocking commas that appear to swirl is a recurrent one which can be traced back to the late 5th century BC.[11] With a view to the much later Chinese symbol, art historians of the La Tène culture refer anachronistically to these clinging pairs as "yin yang".[1]

Early Celtic yin yangs are typically not treated for themselves alone, but appear as part of larger floral or animal ornament, such as revolving leaves at the bottom of a palmette or stylized tails of seahorses.[11] In the 3rd century BC, a more geometrical style develops in which the yin yang now figures as a principal ornamental motif.[11] It is not clear whether the Celts attributed any symbolic value to the emblem, but in those cases where it is placed prominently, such as on the upper end of a scabbard, its use seems to have been apotropaic.[12]

Unlike the classic Taoist symbol, the Celtic yin yang whorls consistently lack the element of mutual penetration, and the two halves are not always portrayed in different colors.[13] In keeping with the dynamic nature of Celtic decor which is characterized by a strong predilection for curvilinear lines, the circles often leave an opening, conveying the impression of the interlocked leaves swirling endlessly around their own axis.[12] Sometimes the yin yang motif is also executed in relief.[12]

The popularity of the design with the Celts is attested by the wide range of artifacts adorned with yin yang roundels. These include beaked flagons, helmets, vases, bowls, collars, hand-pins, cross-slabs, brooches and knife blades.[14] While Celtic iconography was gradually replaced by Roman art on the continent, its revival in post-Roman Britain and persistence in Ireland (see Insular art) also saw the resurgence of the ancient yin yang motif. The comma-shaped whorls in a triskele layout in the famous 7th century Book of Durrow (folio 3v) are a similar case.[15]

Etruscans[편집]

In Etruscan art, the yin yang motif arrives at the end of the 4th century BC, possibly due to the rising Celtic trans-alpine influence.[2] It appears in large size on the belly of two oenochoe excavated in a Falisci tomb, showing a fusion of Etruscan floral ornament with the geometrical pattern by now typical of the Celtic yin yang.[2]

Romans[편집]

A mosaic in a Roman villa in Sousse, Tunisia, features differently colored halves separated by an S-shaped line, but still omits the dots.[13]

The classical yin yang pattern appears, for the first time,[3] in the Roman Notitia Dignitatum, an ancient collection of shield patterns of the Roman army.[17] The shield collection which dates to ca. AD 430 has survived in three manuscript copies.[16][18][19] These show the emblem of an infantry unit called the armigeri defensores seniores ("shield-bearers") to be graphically identical in all but color to the classic Taoist taijitu.[20] Another Western Roman detachment, the Pseudocomitatenses Mauri Osismiaci, used an insignia with the same 'fish-like' form that had dots in one color.[20] An infantry regiment, the Legion palatinae Thebaei, had a pattern for its shields that also appears in taijitu: three concentric circles vertically divided into two halves of opposite and alternating colors, so that, on each side, the two colors follow one another in the inverse order of the opposite half.[20] The Roman symbols predate the taijitu by several hundred years:

As for the appearance of the iconography of the "yin-yang" in the course of time, it was recorded that in China the first representations of the yin-yang, at least the ones that have reached us, go back to the eleventh century AD, even though these two principles were spoken of in the fourth or fifth century BC. With the Notitia Dignitatum we are instead in the fourth or fifth century AD, therefore from the iconographic point of view, almost seven hundred years earlier than the date of its appearance in China.[20]

Gallery[편집]

-

Ancient form of the Taijitu, as used by Lai Zhide

-

Bat Quai Do: Taijitu with I Ching trigrams

-

(Taegeuk in Korean) in the flag of South Korea

-

Yin yang swirls on a Celtic gold-plated bronze disc (early 4th century BC)

-

Shield pattern of the Roman Mauri Osismiaci (ca. AD 430), with the dots in each part kept in the same shade of color[20]

In Unicode[편집]

Unicode features the taijitu in the Miscellaneous Symbols block, at code point U+262F YIN YANG (☯). The related "double body symbol" is included at U+0FCA TIBETAN SYMBOL NOR BU NYIS -KHYIL (࿊), in the Tibetan block, among other symbols used in religious texts.

See also[편집]

Similar symbols:

References[편집]

- ↑ 가 나 Peyre 1982, 62−64, 82 (pl. VI)쪽; Harding 2007, 68f., 70f., 76, 79, 84, 121, 155, 232, 239, 241f., 248, 253, 259쪽; Duval 1978, 282쪽; Kilbride-Jones 1980, 127 (fig. 34.1), 128쪽; Laing 1979, 79쪽; Verger 1996, 664쪽; Laing 1997, 8쪽; Mountain 1997, 1282쪽; Leeds 2002, 38쪽; Morris 2003, 69쪽; Megaw 2005, 13쪽

- ↑ 가 나 다 Peyre 1982, 62−64쪽

- ↑ 가 나 다 Monastra 2000; Nickel 1991, 146, fn. 5쪽; White & Van Deusen 1995, 12, 32쪽; Robinet 2008, 934쪽

- ↑ Peyre 1982, 62f.쪽

- ↑ 가 나 Robinet 2008, 934쪽

- ↑ Xinzhong Yao (2000년 2월 13일). 《An introduction to Confucianism》. Cambridge University Press. 98–쪽. ISBN 978-0-521-64430-3. 2011년 10월 29일에 확인함.

- ↑ Davis, Barbara (2004). 《Taijiquan Classics》. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. 212쪽. ISBN 978-1-55643-431-0.

- ↑ Adler, Joseph A. (1999). "Zhou Dunyi: The Metaphysics and Practice of Sagehood", in Sources of Chinese Tradition, William Theodore De Bary and Irene Bloom, eds. 2nd ed., 2 vols. Columbia University Press. pp. 673-674.

- ↑ http://xingyimax.com/more-about-taiji-symbols-of-ukraine-pavilion-at-expo-2010/

- ↑ http://zyq.com.ua/%D1%96%D0%BD%D1%8C-%D1%8F%D0%BD-%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BF%D1%96%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B0-%D0%BA%D1%83%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%82%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B0/

- ↑ 가 나 다 Peyre 1982, 62−64, 82 (pl. VI)쪽

- ↑ 가 나 다 Duval 1978, 282쪽

- ↑ 가 나 Duval 1978, 282쪽; Monastra 2000

- ↑ Harding 2007, 70f., 76, 79, 155, 232, 241f., 248, 259쪽; Kilbride-Jones 1980, 128쪽

- ↑ Harding 2007, 253쪽

- ↑ 가 나 Late Roman Shield Patterns. Notitia Dignitatum: Magister Peditum 인용 오류: 잘못된

<ref>태그; "Late Roman Shield Patterns"이 다른 콘텐츠로 여러 번 정의되었습니다 - ↑ Altheim 1951, 82쪽; Fink & Ahrens 1984, 104쪽; Benoist 1998, 116쪽; Sacco 2003, 18쪽

- ↑ Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 10291 (I): Mauri Osismiaci; Armigeri; Thebei

- ↑ Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 10291 (II): Mauri Osismiaci; Armigeri; Thebei

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 Monastra 2000

Sources[편집]

Taoist symbolism

- Robinet, Isabelle (2008), 〈Taiji tu. Diagram of the Great Ultimate〉, Pregadio, Fabrizio, 《The Encyclopedia of Taoism A−Z》, Abingdon: Routledge, 934−936쪽, ISBN 978-0-7007-1200-7

European iconography

- Altheim, Franz (1951), 《Attila und die Hunnen》, Baden-Baden: Verlag für Kunst und Wissenschaft

- Benoist, Alain de (1998), 《Communisme et nazisme: 25 réflexions sur le totalitarisme au XXe siècle, 1917-1989》, ISBN 2-86980-028-2

- Duval, Paul-Marie (1978), 《Die Kelten》, München: C. H. Beck, ISBN 3-406-03025-4

- Fink, Josef; Ahrens, Dieter (1984), “Thiasos ton mouson. Studien zu Antike und Christentum”, 《Archiv für Kulturgeschichte》 20, ISBN 3-412-05083-0

- Harding, D. W. (2007), 《The Archaeology of Celtic Art》, Routledge, ISBN 0-203-69853-3

- Kilbride-Jones, H. E. (1980), 《Celtic Craftsmanship in Bronze》, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0387-1

- Laing, Lloyd (1979), 《Celtic Britain》, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 0-7100-0131-2

- Laing, Lloyd (1997), 《Later Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland》, Shire Publications LTD, ISBN 0-85263-874-4

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (2002), 《Celtic Ornament in the British Isles》, E. T. Leeds, ISBN 0-486-42085-X

- Megaw, Ruth and Vicent (2005), 《Early Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland》, Shire Publications LTD, ISBN 0-7478-0613-6

- Monastra, Giovanni (2000), “The "Yin-Yang" among the Insignia of the Roman Empire?”, 《Sophia》 6 (2)

- Morris, John Meirion (2003), 《The Celtic Vision》, Ylolfa, ISBN 0-86243-635-4

- Mountain, Harry (1997), 《The Celtic Encyclopedia》 5, ISBN 1-58112-894-0

- Nickel, Helmut (1991), “The Dragon and the Pearl”, 《Metropolitan Museum Journal》 26: 139–146, doi:10.2307/1512907

- Peyre, Christian (1982), 〈Y a-t’il un contexte italique au style de Waldalgesheim?〉, Duval, Paul-Marie; Kruta, Venceslas, 《L’art celtique de la période d’expansion, IVe et IIIe siècles avant notre ère》, Hautes études du monde gréco-romain 13, Paris: Librairie Droz, 51–82 (62–64, 82)쪽, ISBN 978-2-600-03342-8

- Sacco, Leonardo (2003), “Aspetti 'storico-religiosi' del Taoismo (parte seconda)”, 《Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni》 (Università di Roma, Scuola di studi storico-religiosi) 27 (1-2)

- Verger, Stéphane (1996), “Une tombe à char oubliée dans l'ancienne collection Poinchy de Richebourg”, 《Mélanges de l'école française de Rome》 108 (2), 641–691쪽

- White, Lynn; Van Deusen, Nancy Elizabeth (1995), 《The Medieval West Meets the Rest of the World》, Claremont Cultural Studies 62, Institute of Mediaeval Music, ISBN 0-931902-94-0

External links[편집]

![]() 위키미디어 공용에 설총/연습장 관련 미디어 자료가 있습니다.

위키미디어 공용에 설총/연습장 관련 미디어 자료가 있습니다.

- More about Taiji Symbols of Ukraine Pavilion at Expo 2010

- The "Yin-Yang" among the Insignia of the Roman Empire?

- Where does the Chinese Yin Yang Symbol Come From?

- Conception of Tai-chi-tu-ku

- Chart of the Great Ultimate (Taiji tu) (from the Golden Elixir website)

태극[편집]

| 불교 |

|---|

|

간킬 ({{|lang|bo|དགའ་འཁྱིལ་|간킬|}},[1] IPA에서의 라싸 방언 표기: /kãkjhiː˥/)혹은 "환희의 수레바퀴"(산스크리트어:아난다-차크라)라 불리는 문양은 동아시아 불교와 티베트 불교에서 의식적인 문양으로 사용된다. 이것은 3개의 소용돌이를 연결한 형태로 한국 불교의 태극과도 유사하다.

간킬은 [[법륜]의 내부에 존재하고, 시킴 주의 깃발에도 묘사가 되어있다.

의미[편집]

In addition to linking the gankyil with the "wish-fulfilling jewel" (Skt. cintamani), Robert Beer makes the following connections:

The gakyil or 'wheel of joy' is depicted in a similar form to the ancient Chinese yin-yang symbol, but its swirling central hub is usually composed of either three or four sections. The Tibetan term dga' is used to describe all forms of joy, delight, and pleasure, and the term 'khyil means to circle or spin. The wheel of joy is commonly depicted at the central hub of the dharmachakra, where its three or four swirls may represent the Three Jewels and victory over the three poisons, or the Four Noble Truths and the four directions. As a symbol of the Three Jewels it may also appear as the "triple-eyed" or wish-granting gem of the chakravartin. In the Dzogchen tradition the three swirls of the gakyil primarily symbolize the trinity of the base, path, and fruit.

— Robert Beer, The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols[2]

The "victory" referred to above is symbolised by the dhvaja or "victory banner".

Wallace (2001: p. 77) identifies the ānandacakra with the heart of the "cosmic body" of which Mount Meru is the epicentre:

In the center of the summit of Mt Meru, there is the inner lotus (garbha-padma) of the Bhagavan Kalacakra, which has sixteen petals and constitutes the bliss-cakra (ananda-cakra) of the cosmic body.[3]

Associated triunes[편집]

Ground, path and fruit[편집]

Three humours of traditional Tibetan medicine[편집]

Attributes connected with the three humors (Sanskrit: tridoshas, Tibetan: Nyipa gsum):

- Desire (Tibetan: འདོད་ཆགས། ’dod chags) is aligned with the humor Wind (Tibetan: རླུང་། Lung rlung, Sanskrit: vata - "air and aether constitution")

- Hatred (Tibetan: ཞེ་སྡང་། zhe sdang) is aligned with the humor Bile (Tibetan: མཁྲིས་པ། Tripa mkhris pa, Sanskrit: pitta - "fire and water constitution")

- Ignorance (Tibetan: གཏི་མུག gti mug) is aligned with the humor Phlegm (Tibetan: བད་ཀན། Badkanbad kan, Sanskrit: kapha - "earth and water constitution").[4]

Three Treasures of Yungdrung Bon[편집]

In Bon, the gankyil denotes the three principal terma cycles of Yungdrung Bon: the Northern Treasure (틀:Bo), the Central Treasure (틀:Bo) and the Southern Treasure (틀:Bo).[5] The Northern Treasure is compiled from texts revealed in Zhangzhung and northern Tibet, the Southern Treasure from texts revealed in Bhutan and southern Tibet, and the Central Treasure from texts revealed in Ü-Tsang near Samye.[5]

Learning, Reflection and Meditation[편집]

- Study ( Tibetan: ཐོས་པ་ thos + pa)

- Reflection ( Tibetan: བསམ་པsam+ pa)

- Meditation ( Tibetan: སྒོམ་པ་ sgom pa)

These three aspects are the mūlaprajñā of the sādhanā of the prajñāpāramitā, the "pāramitā of wisdom". Hence, these three are related to, but distinct from, the Prajñāpāramitā that denotes a particular cycle of discourse in the Buddhist literature that relates to the doctrinal field (kṣetra[6]) of the second turning of the dharmacakra.

Mula dharmas of the path[편집]

The Dzogchen teachings focus on three terms:

- View (Tibetan: ལྟ་བ་ lta-ba),

- Meditation (Tibetan: སྒོམ་པ་ sgom pa),

- Action (Tibetan: སྤྱོད་པ་ spyod-pa).

Essence, Nature and Energy[편집]

An important Dzogchen doctrinal view on the Sugatagarbha qua 'Base' (gzhi) (refer: Duckworth, 2008) that foregrounds this is 'essence' (ngo bo), 'nature' (rang bzhin) and 'power' (thugs rje): the triune of which are indivisible and iconographically represented by the Gankyil. Where essence is openness or emptiness (ngo bo stong pa), nature is luminosity, lucidity or clarity (as in the luminous mind of the Five Pure Lights) (rang bzhin gsal ba) and power is universal compassionate energy (thugs rje kun khyab), unobstructed (ma 'gags pa)[7]

Triratna doctrine[편집]

The Triratna, Triple Jewel or Three Gems are triunic are therefore represented by the Gankyil:

- Buddha (Tibetan: སངས་རྒྱས་, Sangye, Wyl. sangs rgyas)

- Dharma (Tibetan: ཆོས་,Cho; Wyl. chos)

- Sangha (Tibetan: དགེ་དུན་,Gendun; Wyl. dge 'dun)

Three Roots[편집]

The Three Roots are:

- Guru (Tibetan: བླ་མ་, Wyl. bla ma)

- Yidam (Tibetan: ཡི་དམ་,Wyl. yi dam; Skt. istadevata)

- Dakini (Tibetan: མཁའ་འགྲོ་མ་, Khandroma; Wyl. mkha 'gro ma )

Three Higher Trainings[편집]

The three higher trainings (Tibetan:ལྷག་བའི་བསླབ་པ་གསུམ་, lhagpe labpa sum,or Wyl. bslab pa gsum)

- discipline (Tibetan: ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་བསླབ་པ་, Wyl. tshul khrims kyi bslab pa)

- meditation (Tibetan: ཏིང་ངེ་འཛན་གྱི་བསླབ་པ་,Wyl. ting nge 'dzin gyi bslab pa)

- wisdom (Tibetan: ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་བསླབ་པ་, Wyl. shes rab kyi bslab pa )

Three Dharma Seals[편집]

The indivisible essence of the Three Dharma Seals (སྡོམ་གསུམ་ or ལྟ་བ་བཀའ་རྟགས་ཀྱི་ཕྱག་རྒྱ་གསུམ་) is embodied and encoded within the Gankyil:

- Impermanence (Tibetan: འདུ་བྱེ་ཐམས་ཅད་མི་རྟག་ཅིང་།)

- anatta (Tibetan: ཆོས་རྣམས་སྟོང་ཞིང་བདག་མེད་པ།)

- Nirvana (Tibetan: མྱང་ངན་འདས་པ་ཞི་བའོ།།)

Three Turnings of the Wheel of Dharma[편집]

As the inner wheel of the Vajrayana Dharmacakra, the gankyil also represents the syncretic union and embodiment of Gautama Buddha's Three Turnings of the Wheel of Dharma. The pedagogic upaya doctrine and classification of the "three turnings of the wheel" was first postulated by the Yogacara school.

Trikaya doctrine[편집]

The gankyil is the energetic signature of the Trikaya, realised through the transmutation of the obscurations forded by the Three poisons (refer klesha) and therefore in the Bhavachakra the Gankyil is an aniconic depiction of the snake, boar and fowl. Gankyil is to Dharmachakra, as still eye is to cyclone, as Bindu is to Mandala. The Gankyil is the inner wheel of the Vajrayana Dharmacakra (refer Himalayan Ashtamangala).

The Gankyil is symbolic of the Trikaya doctrine of nirmanakaya, sambhogakaya and dharmakaya and also of the Buddhist understanding of the interdependence of the Three Vajras: of body, voice and mind. The divisions of the teaching of Dzogchen are for the purposes of explanation only; just as the Gankyil divisions are understood to dissolve in the energetic whirl of the Wheel of Joy.

Three cycles of Nyingmapa Dzogchen[편집]

The Gankyil also embodies the three cycles of Nyingma Dzogchen codified by Mañjuśrīmitra:

This classification determined the exposition of the Dzogchen teachings in the subsequent centuries.

Three Spheres[편집]

"Three spheres" (Sanskrit: trimandala; Tibetan: 'khor gsum). The conceptualizations pertaining to:

- subject,

- object, and

- action[8]

Sound, light and rays[편집]

The triunic continuua of the esoteric Dzogchen doctrine of 'sound, light and rays' (Wylie: sgra 'od zer gsum) is held within the energetic signature of the Gankyil. The doctrine of 'Sound, light and rays' is intimately connected with the Dzogchen teaching of the 'three aspects of the manifestation of energy'. Though thoroughly interpenetrating and nonlocalised, 'sound' may be understood to reside at the heart, the 'mind'-wheel; 'light' at the throat, the 'voice'-wheel; and 'rays' at the head, the 'body'-wheel. Some Dzogchen lineages for various purposes, locate 'rays' at the Ah-wheel (for Five Pure Lights pranayama) and 'light' at the Aum-wheel (for rainbow body), and there are other enumerations.

Three lineages of Nyingmapa Dzogchen[편집]

The Gankyil also embodies the three tantric lineages as Penor Rinpoche,[9] a Nyingmapa, states:

According to the history of the origin of tantras there are three lineages:

- The Lineage of Buddha's Intention, which refers to the teachings of the Truth Body originating from the primordial Buddha Samantabhadra, who is said to have taught tantras to an assembly of completely enlightened beings emanated from the Truth Body itself. Therefore, this level of teaching is considered as being completely beyond the reach of ordinary human beings.

- The Lineage of the Knowledge Holders corresponds to the teachings of the Enjoyment Body originating from Vajrasattva and Vajrapani, whose human lineage begins with Garab Dorje of the Ögyan Dakini land. From him the lineage passed to Manjushrimitra, Shrisimha and then to Guru Rinpoche, Jnanasutra, Vimalamitra and Vairochana who disseminated it in Tibet.

- Lastly, the Human Whispered Lineage corresponds to the teachings of the Emanation Body, originating from the Five Buddha Families. They were passed on to Shrisimha, who transmitted them to Guru Rinpoche, who in giving them to Vimalamitra started the lineage which has continued in Tibet until the present day.

Three aspects of energy in Dzogchen doctrine[편집]

The Gankyil also embodies the energy manifested in the three aspects that yield the energetic emergence[10] (Tibetan: rang byung) of phenomena (Sanskrit: dharmas) and sentient beings (Tibetan: yid can):

- dang (Wylie: gDangs), which is essentially infinite and formless

- rolpa (Wylie: Rol-pa), which may be perceived as the thoughtform of "the eye of the mind", or the transpersonal imaginal manifestation

- tsal (Wylie: rTsal, which may be conceived as the manifestation of the energy of the individual, as apparently an 'external' world.[11]

Though not discrete correlates, dang equates to dharmakaya; rolpa to sambhogakaya; and tsal to nirmanakaya.

Shang[편집]

The gankyil is the central part of the 'shang' (Tibetan: gchang), a traditional ritual tool and instrument of the Bönpo shaman.

Historical context and cross-cultural cognates[편집]

The Gankyil has been equated or conflated with similar Triskelion symbols.

Herbert V. Günther, when writing[12] about Buddhist triunes, states that "...the magical number Three, [is] so deeply rooted in our very being" and references this inference by citing the Russian mathematician V.V. Nalimov (1982: p. 165-168) who according to Gunther provides a concise presentation of why "all of us prefer the trinity: trilogy, triptych...".

Korean philosophy[편집]

Shin-Myeong[편집]

Shin-Jung[편집]

See also[편집]

www.gankyil.org Dharma Study Group www.gankyil.com

Notes and references[편집]

- ↑ Source: dga' 'khyil (accessed: December 11, 2008)

- ↑ Beer (2003) p.209.

- ↑ Wallace, Vesna A. (2001). The Inner Kalacakratantra: A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual. Oxford University Press. Source: [1] (accessed: Saturday March 14, 2009)

- ↑ Besch (2006).

- ↑ 가 나 M. Alejandro Chaoul-Reich (2000). "Bön Monasticism". Cited in: William M. Johnston (author, editor) (2000). Encyclopedia of monasticism, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-57958-090-4, ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2. Source: [2] (accessed: Saturday April 24, 2010), p.171

- ↑ Southworth.

- ↑ Petit, John Whitney (1999). Mipham's Beacon of Certainty: Illuminating the View of Dzochen, the Great Perfection. Boston: Wisdom Publications (1999). ISBN 0-86171-157-2Source: [3] (accessed: Friday April 9, 2010, p.78-79

- ↑ Thub-bstan-chos-kyi-grags-pa, Chokyi Dragpa, Heidi I. Koppl, Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche (2004). Uniting Wisdom and Compassion: Illuminating the thirty-seven practices of a bodhisattva. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-377-X. Source: [4] (accessed: February 4, 2009) p.202

- ↑ Penor Rinpoche. (accessed: 1 February 2007)

- ↑ For a sound introduction to "emergence" refer: Corning, Peter A. (2002). The Re-emergence of "Emergence": A Venerable Concept in Search of a Theory. Institute For the Study of Complex Systems. NB: initially published in and © by Complexity (2002) 7(6): pp.18-30. Source: [5] (accessed: February 5, 2008)

- ↑ Norbu (1999), pp. 99, 100, 101

- ↑ Guenther.

Bibliography[편집]

- Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. ISBN 1-932476-03-2 Source: [6] (accessed: December 7, 2007)

- Besch, {Nils} Florian (2006). Tibetan Medicine Off the Roads: Modernizing the Work of the Amchi in Spiti. Source: [7] (accessed: February 11, 2008)

- Günther, Herbert (undated). Three, Two, Five. [8] (accessed: April 30, 2007)

- Ingersoll, Ernest (1928). Dragons and Dragon Lore. [9] (accessed: June 12, 2008)

- Norbu, Chögyal Namkhai Rinpoche (Edited by John Shane) (1988). The Crystal and the Way of Light.. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-14-019084-8

- Norbu, Chögyal Namkhai (Edited by John Shane) (1999). The Crystal and The Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-135-9

- Kazin, Alfred (1946). The Portable Blake. (Selected and arranged with an introduction by Alfred Kazin.) New York: The Viking Press.

- Nalimov, V. V. (1982). Realms of the Unconscious: The Enchanted Frontier. University Park, PA: ISI Press.

- Penor Rinpoche (undated). The school of Nyingma thought [10] (accessed: June 12, 2008)

- Southworth, Franklink C. (2005? forthcoming). Proto-Dravidian Agriculture. Source: [11] (accessed: February 10, 2008)

- Van Schaik, Sam (2004). Approaching the Great Perfection: Simultaneous and Gradual Methods of Dzogchen Practice in the Longchen Nyingtig. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-370-2. Source: [12] (accessed: February 2, 2008)

- Wayman, Alex (?) A Problem of 'Synonyms' in the Tibetan Language: Bsgom pa and Goms pa. Source: [to be supplied when have more bandwidth] (accessed: February 10, 2008) NB: published in the The Journal of the Tibet Society.

External links[편집]

- Henkemans, Anneco Blanson (1996). The Gakayil And The Windmill Hill Formation. (accessed: Tuesday, February 6, 2007)

- Entry for dga' 'khyil in Rang Jung Yeshe Wiki (with picture).

Gankyil buddhist community www.gankyil.com www.gankyil.org

| 이석영 이석영 | |

|---|---|

| 출생 | 1969년 월 일 |

| 거주지 | |

| 국적 | |

| 학력 | 대한민국, 연세대학교 천문우주학과 학사, 예일대학교, 천문학] 박사 |

| 직업 | 천문학자, 대학 교수 |

| 소속 | 연세대학교 천문우주학과 교수 |