사용자:구순돌/연습장/평화

평화(平和, 영어: peace)는 좁은 의미로는 '전쟁을 하지 않는 상태'이지만 현대 평화학에서는 평화를 '분쟁과 다툼이 없이 서로 이해하고, 우호적이며, 조화를 이루는 상태'로 이해한다.[3] 인류가 목표로 하는 가장 완전(完全)한 상태이다. 평화는 적대감과 폭력의 부재에서 사회적 우정과 화합의 개념이다. 사회적 의미에서, 평화는 일반적으로 갈등의 부족을 의미하는데 사용된다. (전쟁과 같은) 그리고 개인이나 집단간의 폭력에 대한 두려움으로부터의 자유를 의미한다. 역사를 통해, 지도자들은 다양한 형태의 합의나 평화 조약을 통해 지역 평화나 경제 성장을 이룬 일종의 행동적 자제를 확립하기 위해 평화조약과 외교를 사용해 왔다. 그러한 행동 규제는 종종 갈등의 감소, 더 큰 경제적 상호작용, 그리고 결과적으로 상당한 번영을 가져왔다.

"심리적 평화" (평화로운 사고와 감정과 같은)는 잘 정의되지는 않았지만, 종종 "평상 평화"를 확립하는 데 필요한 전제조건 중 하나이다. 평화로운 행동은 때때로 "평화로운 내적 기질"에서 비롯된다. 어떤 사람들은 평화는 일상 생활의 불확실성에 의존하지 않는 내면의 평온함이라는 어떤 특성으로 시작될 수 있다는 믿음을 표현했다.[4] 자신과 타인을 위한 그러한 "평화로운 내부적 처분"의 획득은 달리 화해할 수 없어 보이는 경쟁적 이해관계를 해결하는 데 기여할 수 있다. 평화는 설레면 행복하지만 설레는 상태가 아니라 마음이 고요하고 만족스러울 때 평화가 온다.

구분[편집]

요한 갈퉁(노르웨이어: Johan Galtung, 1930년 ~ , 노르웨이의 평화학자)은 그의 저서 《평화적 수단에 의한 평화》[5]에서 평화를 직접적인 폭력이 없는 상태인 소극적 평화와 갈등을 비폭력적 방식으로 해결하는 적극적 평화로 구분하였다.

소극적 평화[편집]

전통적 의미에서 평화는 ‘전쟁의 부재’, ‘세력의 균형' 상태로 설명된다. 인류 역사상 평화의 시기는 거의 존재하지 않았거나, 극히 짧았다(30년 전쟁, 12년 전쟁, 그리고 소소한 수많은 전쟁을 고려해 보았을 때). 그러므로 단순히 전쟁이 없는 상태를 유지하려면 타인으로부터 공격당하지 않기 위한 전쟁 억지력이 반드시 필요하다. 즉, 소극적 평화는 강자가 폭력으로 약자를 억누름으로써 유지되는 평화, 비판적으로 말한다면 평화유지를 명분으로 약자의 저항을 억누르는 폭력(Pax Romana, Pax Americana)이 소극적 평화이다. 그래서 비폭력주의 교회의 하나인 후터라이트교회의 장로인 요한 크리스토프 아놀드는 소극적 평화는 약자의 목을 조르면서 "조용히 해. 평화를!"이라고 윽박지르는 가짜 평화라고 비판했다.[6]

적극적 평화[편집]

마하트마 간디는 평화를 단순히 전쟁이 없는 상황이 아니라, 정의가 구현된 상황으로 보았다. 같은 맥락에서 마틴 루서 킹 목사는 "진정한 평화는 단지 긴장이 없는 상태만을 말하는 것이 아니라, 정의가 실현되는 것을 말한다"라고 말했다. 스위스의 진보적 사회학자인 장 지글러도 테러리스트들의 대부분이 가난과 좌절로 인해 사회에 대한 불만이 많은 빈민 출신이라는 사실을 근거로 평화는 테러와의 전쟁이 아닌, 사람이 사람답게 사는 사회가 건설될 때에 실현될 수 있다고 지적한다.[7]

대부분의 종교에서 평화는 적극적으로 이루어야 하는 목표이다. 예를 들어 유대교는 십계명을 통해 살인[8]하지 말라고 가르친다. 요즘 이스라엘이 팔레스타인 군인 및 민간인을 대상으로 한 국가 방위 수준을 넘어선 무차별 살상과 인권침해행위에 대해 십계명이 제대로 지켜지고 있지 않다는 비판이 있다.[9]

다양한 평화의 의미[편집]

살람(Salaam)[편집]

이슬람에서 인사할 때에는 이마에 손바닥을 대고 ‘살람’이라고 인사하면 된다. 무슬림의 교리에 따르면 인간은 처음 태어날 때 ‘이슬람(Islam)' 상태로 태어난다. 이슬람 상태는 사랑으로 충만하고, 평화롭고, 나쁜 생각으로 더럽혀지지 않은 상태를 뜻한다. 그 뒤, 인간이 갖는 증오와 미움, 공격적인 성향은 사탄(Shaytan)의 영향이며, 수양으로 극복해야 할 대상이다.

내적 평화[편집]

평화는 신체와 마음, 영혼의 상태로도 해석된다. 'Sevi Regis'에 따르면 내적 평화에 필요한 요소는 ‘평온(restfulness), 조화(harmony), 균형(balance), 평정심(equilibrium), 장수(longevity), 정의(justice), 결단력(resolution), 시간에 구애받지 않음(timelessness), 만족(contentment), 자유(freedom), 성취(fulfillment)’이다.

자연, 우주와의 조화[편집]

중부 아프리카 그레이트 레익스(Great Lakes) 지역의 원주민들은 평화를 킨도키(kindoki)라고 부른다. 이는 인간 사이의 조화뿐 아니라 인간과 자연, 우주의 조화를 뜻하는 보다 넓은 개념으로 사용된다.

용서와 화해[편집]

그리스도교적인 평화주의 사상가인 데스몬드 투투 성공회 대주교는 《용서없이 미래없다》(홍성사 刊)에서 아프리카에는 다른 사람의 잘못을 용서할 수 있는 너그러움을 뜻하는 우분투라는 전통이 있다고 설명한다. 그 근거로 남아프리카 공화국의 인종차별이 법으로는 종식된 이후 진행된 과거사 청산은 우분투 전통에 의해 인종차별 시대 당시 백인정권에 의해 자행된 반인권적인 폭력의 가해자들이 죄를 고백하면 사법적인 면책을 허용하는 정직과 용서 위주로 진행되었다. 이러한 노력은 남아프리카 공화국이 인종차별로 인한 갈등을 해소함으로써 남아프리카 공화국에 평화가 정착되게 하였다.

없거나 혹은 어디에나 있는 것[편집]

어떤 이들은 평화란 정확히 정의할 수 없는 개념이라고 말한다. ‘언젠가 이루어야 할’, 또는 ‘지켜내야 할’ 평화는 없으며, ‘유토피아’, ‘행복’과 같이 개념으로만 존재할 뿐이라는 설명이다. 대신에 그들은 모두의 평범한 일상에서 소소한 평화를 만들고 확장할 것을 주장한다. 즉 평화는 어떤 고정된 의미가 아니며, 일상에서 항상 다른 의미로 존재한다.

성서에서 말하는 평화[편집]

구약성서에서는 평화라는 말로 샬롬이라는 말을 쓴다. 샬롬은 모든 사람을 위한 전쟁과 갈등의 종식, 평안과 구원을 뜻하는데, 개인과 개인, 사람과 국가, 하느님과 인간의 관계에 적용된다. 더 나아가 샬롬은 정의와도 관련이 있는데, 이는 평화가 정의로운 인간관계를 통해 이루어지기 때문이다. 여기에는 자신의 원수까지도 사랑하고 그를 위해 평화와 안정을 기원하는 보편적인 사랑도 포함된다. 신약성서에서는 예수 그리스도를 평화의 상징이자, 평화를 위한 도구로 그리고 하느님의 평화를 담고 있는 존재로 해석하고 있으며[10], 그리스도의 십자가와 성육신을 통해 만물의 화해와 일치가 이루어졌다고 고백한다.[11]

평화 순위[편집]

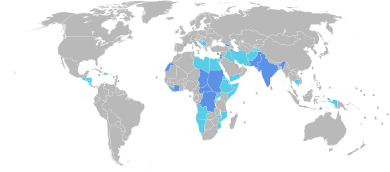

보통 평화는 무형의 개념으로 생각되지만, 많은 단체들은 평화를 계량화하려고 노력하고 있다. 경제 평화 연구소가 발표하는 세계 평화 지수는 그런 노력중 하나로, 평화의 존재/부재에 따라 나라들을 23개의 지표로 평가한다. 가장 최근의 지수는 158개의 나라를 내적, 외적의 평화로 순위를 매긴다. 2012년 자료에 따르면, 아이슬란드가 세계에서 가장 평화로운 나라이고, 소말리아는 제일 평화롭지 않은 나라이다. 평화 기금의 실패한 국가 지수는 폭력과 불안정의 위험에 집중하여 177개의 나라를 평가한다. 이 지수는 12개의 사회경제적, 정치적, 군사적 지표로 나라가 얼마나 취약한지에 따라 순위를 매긴다. 2012년 자료는 가장 취약한 나라는 소말리아이고 가장 안정적인 나라는 핀란드라고 보고했다. 메릴랜드 대학교는 평화와 분쟁 불안정성 레저 (Peace and Conflict Instabilty Ledger)를 발표한다. 이 레저는 3년동안의 정치적 불안정과 무력분쟁에 집중하여 5개의 지표로 163개의 나라를 평가한다. 가장 최근[언제?]의 레저에 따르면 슬로베니아가 가장 평화로운 나라이고 아프가니스탄은 가장 분쟁이 많은 나라이다. 이밖에도 이코노미스트 인텔리전스 유닛과 조지 메이슨 대학교 등 많은 단체들이 평화를 계량화하려는 지표를 발표한다.

어원학[편집]

'평화'라는 용어는 가장 최근에 "평화, 화해, 침묵, 합의" (11세기)를 의미하는 영불 페스와 고대 프랑스 페스에서 유래했다.[12] 앵글로-프랑스 용어 자체는 "평화, 콤팩트, 합의, 평화 조약, 평화, 적대감의 부재, 화합"을 의미하는 라틴어 pax에서 유래했다. 이 영어 단어는 1300년경부터 히브리어 샬롬을 번역한 것으로 다양한 개인적인 인사에서 사용되었는데, 유대 신학에 따르면, 이 단어는 '완전하게, 전체로'를 의미하는 히브리어 동사에서 유래했다.[13] 비록 '평화'가 일반적인 번역이지만, 아랍어 살람과 같은 뜻인 '샬롬'은 평화 외에도 정의, 건강, 안전, 안녕, 번영, 형평, 안전, 행운, 그리고 친근함뿐만 아니라 단순히 인사인 "안녕"과 "안녕"을 의미하는 여러 가지 다른 의미를 가지고 있기 때문이다.[14] 개인적인 차원에서, 평화로운 행동은 친절하고, 사려 깊고, 존중하고, 정의롭고, 다른 사람들의 믿음과 행동에 관용적이며, 호의적인 경향이 있다.

평화에 대한 이 후자의 이해는 또한 1200년경의 유럽의 참고 문헌에서 발견되었듯이, 자신의 마음 속에 "평화롭게" 있는 것과 같이, 개인의 자기 자신에 대한 내성적인 감각이나 개념과도 관련될 수 있다. 초기 영어 용어는 또한 "조용하다"라는 의미로 사용되었는데, 이는 다툼을 피하고 평온을 추구하는 가족이나 집단의 관계에 대한 차분하고, 평온하고, 명상적인 접근을 반영한다.

많은 언어에서 평화를 뜻하는 단어는 인사나 작별 인사로 사용되기도 하는데, 예를 들어 하와이 단어 알로하와 아랍어 단어 살람이 그렇다. 영어에서 평화라는 단어는 때때로 작별 인사로 사용되는데, 특히 죽은 사람을 위한 용어로, 안식을 위한 용어로 사용된다.

볼프강 디트리히는 저서 "평화 연구의 팔그레이브 국제 핸드북" (2011)으로 이끈 그의 연구 프로젝트에서, 전 세계의 다른 언어와 지역에서 평화의 다른 의미들을 지도화한다. 나중에, 그의 역사와 문화의 평화 해석 (2012)에서, 그는 평화의 다른 의미들을 다섯 개의 평화 가족으로 분류한다: 에너지/조화, 도덕/정의, 현대/안보, 포스트모던/진실, 그리고 이전 네 가족과 사회의 긍정적인 측면을 종합한 트랜스레이셔널을 의미하기도 한다.

역사[편집]

고대와 더 최근에, 다른 나라들 사이의 평화적인 동맹은 왕실 결혼을 통해 성문화되었다. 기원전 800년경 헤르모디케 1세와 기원전 600년경 헤르모디케 2세는 아가멤논 왕가의 그리스 공주로, 지금의 중앙 터키에서 온 왕들과 결혼했다. 프리기아/리디아와 아이올리아 그리스인의 결합은 지역 평화를 가져왔으며, 이는 고대 그리스에 획기적인 기술력의 이전을 촉진시켰다; 각각 다음과 같은데, 음성 문자 및 동전 주조(주화 가치가 국가에 의해 보장되는 토큰 통화를 사용하는 경우)[15] 두 발명품 모두 주변국들에 의해 추가적인 무역과 협력을 통해 빠르게 채택되었고 문명의 진보에 근본적인 도움이 되었다.

역사를 통틀어 승자는 때때로 패배자에게 평화를 강요하기 위해 무자비한 수단을 사용해왔다.로마의 역사가 타키투스는 그의 저서 아그리콜라에서 로마의 탐욕과, 탐욕에 대한 웅변적이고 악랄한 논쟁을 담고 있다. 하나는, 타키투스가 말한 칼레도니아 족장 칼가쿠스의 말인데, 그 끝은: "Auferre trucidare rapere falsis nominibus imperium, atque ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant." (파괴하고, 도살하고, 거짓된 칭호로 찬탈하는 것을 제국이라 부르고, 사막을 만드는 것을 평화라 부른다. — 옥스퍼드 수정 번역)이다.

그러므로 평화에 대한 논의는 그것의 형태에 대한 논의이다. 그것은 단순히 대규모 조직적인 살육의 부재인가, 아니면 평화는 특정한 도덕과 정의를 필요로 하는가? (정당한 평화)[16] 평화는 적어도 두 가지 형태로 보여져야 한다:

- 무기의 단순한 침묵, 전쟁의 부재

- 전쟁의 부재는 정의, 상호 존중, 법률 및 선의와 같은 용어로 특징지어지는 상호 관계의 해결을 위한 특별한 요건을 수반한다.

보다 최근에는 사법 제도의 급진적인 개혁을 옹호하는 사람들이 비형벌적이고 비폭력적인 복원적 사법 방법의 공공 정책 채택을 요구하고 있다. 회복적 정의에 관한 유엔 작업 그룹을 포함하여 이러한 방법의 성공을 연구하는 많은 사람들은 평화와 관련된 용어로 정의를 다시 정의하려고 시도했다. 2000년대 후반부터 정의를 더 큰 평화 이론에 개념적으로 통합하는 능동적 평화 이론이 제안되었다. 보관됨 26 7월 2011 - 웨이백 머신

평화에 대한 또 다른 국제적으로 중요한 접근법은 분쟁 발생 시 문화재에 대한 국제적, 국가적, 지역적 보호이다. 유엔, 유네스코, 블루쉴드 인터내셔널은 문화유산의 보호를 다루고 있다. 이는 유엔 평화유지군의 통합에도 적용된다. 이리나 보코바 유네스코 사무총장은 다음과 같이 말했다: "문화와 유산의 보호는 복원력, 화해, 평화를 위한 길을 열어주는 인도적, 안보적 정책이다." 문화유산의 보호는 특히 민감한 문화적 기억, 증가하는 문화적 다양성, 그리고 국가, 지방 자치체 또는 지역의 경제적 기반을 보존해야 한다. 많은 분쟁에서 상대방의 문화유산을 파괴하려는 의도적인 시도가 있다.문화 이용자 혼란이나 문화유산과 도주 원인 사이에는 연관성이 있다. 그러나, 보호는 지역 주민들과 함께 군부대와 민간 인력의 근본적인 협력과 훈련을 통해서만 지속 가능한 방식으로 시행될 수 있다. 카를 폰 합스부르크 블루 실드 인터내셔널 회장은 "지역 공동체와 지역 참여자가 없다면, 그것은 완전히 불가능하다"라는 말로 요약했다.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

단체 및 경품[편집]

United Nations[편집]

The United Nations (UN) is an international organization whose stated aims are to facilitate cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achieving world peace. The UN was founded in 1945 after World War II to replace the League of Nations, to stop wars between countries, and to provide a platform for dialogue.

After authorization by the Security Council, the UN sends peacekeepers to regions where armed conflict has recently ceased or paused to enforce the terms of peace agreements and to discourage combatants from resuming hostilities. Since the UN does not maintain its own military, peacekeeping forces are voluntarily provided by member states of the UN. The forces, also called the "Blue Helmets", who enforce UN accords are awarded United Nations Medals, which are considered international decorations instead of military decorations. The peacekeeping force as a whole received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1988.

Police[편집]

The obligation of the state to provide for domestic peace within its borders in usually charged to the police and other general domestic policing activities. The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state to enforce the law, to protect the lives, liberty and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder.[23] Their powers include the power of arrest and the legitimized use of force. The term is most commonly associated with the police forces of a sovereign state that are authorized to exercise the police power of that state within a defined legal or territorial area of responsibility. Police forces are often defined as being separate from the military and other organizations involved in the defense of the state against foreign aggressors; however, gendarmerie are military units charged with civil policing.[24] Police forces are usually public sector services, funded through taxes.

National security[편집]

It is the obligation of national security to provide for peace and security in a nation against foreign threats and foreign aggression. Potential causes of national insecurity include actions by other states (e.g. military or cyber attack), violent non-state actors (e.g. terrorist attack), organised criminal groups such as narcotic cartels, and also the effects of natural disasters (e.g. flooding, earthquakes).[25]:v, 1–8[26] Systemic drivers of insecurity, which may be transnational, include climate change, economic inequality and marginalisation, political exclusion, and militarisation.[26] In view of the wide range of risks, the preservation of peace and the security of a nation state have several dimensions, including economic security, energy security, physical security, environmental security, food security, border security, and cyber security. These dimensions correlate closely with elements of national power.

League of Nations[편집]

The principal forerunner of the United Nations was the League of Nations. It was created at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, and emerged from the advocacy of Woodrow Wilson and other idealists during World War I. The Covenant of the League of Nations was included in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, and the League was based in Geneva until its dissolution as a result of World War II and replacement by the United Nations. The high hopes widely held for the League in the 1920s, for example amongst members of the League of Nations Union, gave way to widespread disillusion in the 1930s as the League struggled to respond to challenges from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Japan.

One of the most important scholars of the League of Nations was Sir Alfred Eckhard Zimmern. Like many of the other British enthusiasts for the League, such as Gilbert Murray and Florence Stawell – known as the "Greece and peace" set – he came to this from the study of the classics.

The creation of the League of Nations, and the hope for informed public opinion on international issues (expressed for example by the Union for Democratic Control during World War I), also saw the creation after World War I of bodies dedicated to understanding international affairs, such as the Council on Foreign Relations in New York and the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Chatham House in London. At the same time, the academic study of international relations started to professionalise, with the creation of the first professorship of international politics, named for Woodrow Wilson, at Aberystwyth, Wales, in 1919.

Olympic Games[편집]

The late 19th century idealist advocacy of peace which led to the creation of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Rhodes Scholarships, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and ultimately the League of Nations, also saw the re-emergence of the ancient Olympic ideal. Led by Pierre de Coubertin, this culminated in the holding in 1896 of the first of the modern Olympic Games.

Nobel Peace Prize[편집]

The highest honour awarded to peace makers is the Nobel Prize in Peace, awarded since 1901 by the Norwegian Nobel Committee. It is awarded annually to internationally notable persons following the prize's creation in the will of Alfred Nobel. According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who "...shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses."[27]

Rhodes, Fulbright and Schwarzman scholarships[편집]

In creating the Rhodes Scholarships for outstanding students from the United States, Germany and much of the British Empire, Cecil Rhodes wrote in 1901 that 'the object is that an understanding between the three great powers will render war impossible and educational relations make the strongest tie'.[28] This peace purpose of the Rhodes Scholarships was very prominent in the first half of the 20th century, and became prominent again in recent years under Warden of the Rhodes House Donald Markwell,[29] a historian of thought about the causes of war and peace.[30] This vision greatly influenced Senator J. William Fulbright in the goal of the Fulbright fellowships to promote international understanding and peace, and has guided many other international fellowship programs,[31] including the Schwarzman Scholars to China created by Stephen A. Schwarzman in 2013.[32]

Gandhi Peace Prize[편집]

The International Gandhi Peace Prize, named after Mahatma Gandhi, is awarded annually by the Government of India. It was launched as a tribute to the ideals espoused by Gandhi in 1995 on the occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth. This is an annual award given to individuals and institutions for their contributions towards social, economic and political transformation through non-violence and other Gandhian methods. The award carries Rs. 10 million in cash, convertible in any currency in the world, a plaque and a citation. It is open to all persons regardless of nationality, race, creed or sex.

Student Peace Prize[편집]

The Student Peace Prize is awarded biennially to a student or a student organization that has made a significant contribution to promoting peace and human rights.

Culture of Peace News Network[편집]

The Culture of Peace News Network, otherwise known simply as CPNN, is a UN authorized interactive online news network, committed to supporting the global movement for a culture of peace.

Sydney Peace Prize[편집]

Every year in the first week of November, the Sydney Peace Foundation presents the Sydney Peace Prize. The Sydney Peace Prize is awarded to an organization or an individual whose life and work has demonstrated significant contributions to:

The achievement of peace with justice locally, nationally or internationally

The promotion and attainment of human rights

The philosophy, language and practice of non-violence

Museums[편집]

A peace museum is a museum that documents historical peace initiatives. Many provide advocacy programs for nonviolent conflict resolution. This may include conflicts at the personal, regional or international level.

Smaller institutions include the Randolph Bourne Institute, the McGill Middle East Program of Civil Society and Peace Building and the International Festival of Peace Poetry..

Religious beliefs [편집]

Religious beliefs often seek to identify and address the basic problems of human life, including conflicts between, among, and within persons and societies. In ancient Greek-speaking areas, the virtue of peace was personified as the goddess Eirene, and in Latin-speaking areas as the goddess Pax. Her image was typically represented by ancient sculptors as a full-grown woman, usually with a horn of plenty and scepter and sometimes with a torch or olive leaves.

Christianity[편집]

Christians, who believe Jesus of Nazareth to be the Jewish Messiah called Christ (meaning Anointed One),[33] interpret Isaiah 9:6 as a messianic prophecy of Jesus in which he is called the "Prince of Peace."[34] In the Gospel of Luke, Zechariah celebrates his son John: And you, child, will be called prophet of the Most High, for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give his people knowledge of salvation through the forgiveness of their sins, because of the tender mercy of our God by which the daybreak from on high will visit us to shine on those who sit in darkness and death's shadow, to guide our feet into the path of peace.

As a testimony of peace, Churches of the Anabaptist Christian tradition (such as the Mennonites), as well Holiness Methodist Pacifists (such as the Immanuel Missionary Church) and Quakers (such as the Conservative Friends), practice nonresistance and do not participate in warfare.[35][36]

In the Catholic Church, numerous pontifical documents on the Holy Rosary document a continuity of views of the Popes to have confidence in the Holy Rosary as a means to foster peace. Subsequently, to the Encyclical Mense maio,1965, in which he urged the practice of the Holy Rosary, "the prayer so dear to the Virgin and so much recommended by the Supreme Pontiffs," and as reaffirmed in the encyclical Christi Matri, 1966, to implore peace, Pope Paul VI stated in the apostolic Recurrens mensis, October 1969, that the Rosary is a prayer that favors the great gift of peace.

Hinduism[편집]

Hindu texts contain the following passages:

May there be peace in the heavens, peace in the atmosphere, peace on the earth. Let there be coolness in the water, healing in the herbs and peace radiating from the trees. Let there be harmony in the planets and in the stars, and perfection in eternal knowledge. May everything in the universe be at peace. Let peace pervade everywhere, at all times. May I experience that peace within my own heart.

— Yajur Veda 36.17)

Let us have concord with our own people, and concord with people who are strangers to us. Ashwins (Celestial Twins,) create between us and the strangers a unity of hearts. May we unite in our minds, unite in our purposes, and not fight against the heavenly spirit within us. Let not the battle-cry rise amidst many slain, nor the arrows of the war-god fall with the break of day

— Yajur Veda 7.52

A superior being does not render evil for evil. This is a maxim one should observe... One should never harm the wicked or the good or even animals meriting death. A noble soul will exercise compassion even towards those who enjoy injuring others or cruel deeds... Who is without fault?

The chariot that leads to victory is of another kind.

- Valour and fortitude are its wheels;

- Truthfulness and virtuous conduct are its banner;

- Strength, discretion, self-restraint and benevolence are its four horses,

- Harnessed with the cords of forgiveness, compassion and equanimity...

- Whoever has this righteous chariot, has no enemy to conquer anywhere.

— Valmiki, Ramayana

Buddhism[편집]

Buddhists believe that peace can be attained once all suffering ends. They regard all suffering as stemming from cravings (in the extreme, greed), aversions (fears), or delusions. To eliminate such suffering and achieve personal peace, followers in the path of the Buddha adhere to a set of teachings called the Four Noble Truths — a central tenet in Buddhist philosophy.

Islam[편집]

Islam derived from the root word salam which literally means peace. Muslims are called followers of Islam. Quran clearly stated "Those who have believed and whose hearts are assured by the remembrance of Allah. Unquestionably, by the remembrance of Allah, hearts are assured" and stated "O you who have believed, when you are told, "Space yourselves" in assemblies, then make space; Allah will make space for you. And when you are told, "Arise," then arise; Allah will raise those who have believed among you and those who were given knowledge, by degrees. And Allah is Acquainted with what you do."[37][38]

Judaism[편집]

The Judaic tradition directly associates God with peace, as evidenced by various principles and laws in Judaism. Shalom, the biblical and modern Hebrew word for peace, is one of the names for God according to the Judaic law and tradition. For instance, in traditional Jewish law, individuals are prohibited from saying "Shalom" when they are in the bathroom as there is a prohibition on uttering any of God's names in the bathroom, out of respect for the divine name. Jewish liturgy and prayer is replete with prayers asking God to establish peace in the world. The Shmoneh Esreh, a key prayer in Judaism that is recited three times each day, concludes with a blessing for peace. The last blessing of the Shmoneh Esreh, also known as the Amida ("standing" as the prayer is said while standing), is focused on peace, beginning and ending with supplications for peace and blessings. Peace is central to Judaism's core principle of Moshaich ("messiah") which connotes a time of universal peace and abundance, a time where weapons will be turned into plowshares and lions will sleep with lambs. As it is written in the Book of Isaiah 2:4 and 11:6-9:

They shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks; nation will not lift sword against nation and they will no longer study warfare.[39]

The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them. The cow will feed with the bear, their young will lie down together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox. The infant will play near the hole of the cobra, and the young child put his hand into the viper's nest. They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, for the earth will be full of the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.[40]

This last metaphor from Tanakh (Hebrew bible) symbolizes the peace that a longed for messianic age will be characterized by, a peace where natural enemies, the strong and the weak, predator and prey, will live in harmony.

Jews pray for the messianic age of peace every day in the Shmoneh Esreh in addition to faith in the coming of the messianic age constituting one of the thirteen core principles of faith in Judaism, according to Maimonides.

Ideological beliefs[편집]

Pacifism[편집]

Pacifism is the categorical opposition to the behaviors of war or violence as a means of settling disputes or of gaining advantage. Pacifism covers a spectrum of views ranging from the belief that international disputes can and should all be resolved via peaceful behaviors; to calls for the abolition of various organizations which tend to institutionalize aggressive behaviors, such as the military, or arms manufacturers; to opposition to any organization of society that might rely in any way upon governmental force. Such groups which sometimes oppose the governmental use of force include anarchists and libertarians. Absolute pacifism opposes violent behavior under all circumstance, including defense of self and others.

Pacifism may be based on moral principles (a deontological view) or pragmatism (a consequentialist view). Principled pacifism holds that all forms of violent behavior are inappropriate responses to conflict, and are morally wrong. Pragmatic pacifism holds that the costs of war and inter-personal violence are so substantial that better ways of resolving disputes must be found.

Inner peace, meditation and prayerfulness[편집]

Psychological or inner peace (i.e. peace of mind) refers to a state of being internally or spiritually at peace, with sufficient knowledge and understanding to keep oneself calm in the face of apparent discord or stress. Being internally "at peace" is considered by many to be a healthy mental state, or homeostasis and to be the opposite of feeling stressful, mentally anxious, or emotionally unstable. Within the meditative traditions, the psychological or inward achievement of "peace of mind" is often associated with bliss and happiness.

Peace of mind, serenity, and calmness are descriptions of a disposition free from the effects of stress. In some meditative traditions, inner peace is believed to be a state of consciousness or enlightenment that may be cultivated by various types of meditation, prayer, t'ai chi ch'uan (太极拳, tàijíquán), yoga, or other various types of mental or physical disciplines. Many such practices refer to this peace as an experience of knowing oneself. An emphasis on finding one's inner peace is often associated with traditions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and some traditional Christian contemplative practices such as monasticism,[41] as well as with the New Age movement.

Non-Aggression Principle[편집]

The Non-Aggression Principle (NAP) asserts that aggression against an individual or an individual's property is always an immoral violation of one's life, liberty, and property rights.[42][43] Utilizing deceit instead of consent to achieve ends is also a violation of the Non-Aggression principle. Therefore, under the framework of the Non-Aggression principle, rape, murder, deception, involuntary taxation, government regulation, and other behaviors that initiate aggression against otherwise peaceful individuals are considered violations of this principle.[44] This principle is most commonly adhered to by libertarians. A common elevator pitch for this principle is, "Good ideas don't require force."[45]

Satyagraha[편집]

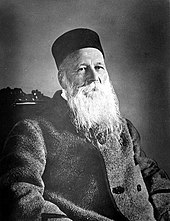

Satyagraha is a philosophy and practice of nonviolent resistance developed by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He deployed satyagraha techniques in campaigns for Indian independence and also during his earlier struggles in South Africa.

The word satyagraha itself was coined through a public contest that Gandhi sponsored through the newspaper he published in South Africa, Indian Opinion, when he realized that neither the common, contemporary Hindu language nor the English language contained a word which fully expressed his own meanings and intentions when he talked about his nonviolent approaches to conflict. According to Gandhi's autobiography, the contest winner was Maganlal Gandhi (presumably no relation), who submitted the entry 'sadagraha', which Gandhi then modified to 'satyagraha'. Etymologically, this Hindic word means 'truth-firmness', and is commonly translated as 'steadfastness in the truth' or 'truth-force'.

Satyagraha theory also influenced Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, and others during the campaigns they led during the civil rights movement in the United States. The theory of satyagraha sees means and ends as inseparable. Therefore, it is contradictory to try to use violence to obtain peace. As Gandhi wrote: "They say, 'means are, after all, means'. I would say, 'means are, after all, everything'. As the means so the end..."[46] A quote sometimes attributed to Gandhi, but also to A. J. Muste, sums it up: "There is no way to peace; peace is the way".

Monuments[편집]

The following are monuments to peace:

| Name | Location | Organization | Meaning | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese Peace Bell | New York City, NY | United Nations | World peace |

|

| Fountain of Time | Chicago, IL | Chicago Park District | 100 years of peace between the US and UK |

|

| Fredensborg Palace | Fredensborg, Denmark | Frederick IV | The peace between Denmark–Norway and Sweden, after Great Northern War which was signed 3 July 1720 on the site of the unfinished palace. |

|

| International Peace Garden | North Dakota, Manitoba | non-profit organization | Peace between the US and Canada, World peace |

|

| Peace Arch | border between US and Canada, near Surrey, British Columbia. | non-profit organization | Built to honour the first 100 years of peace between Great Britain and the United States resulting from the signing of the Treaty of Ghent in 1814. |

|

| Statue of Europe | Brussels | European Commission | Unity in Peace in Europe |

|

| Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park | Alberta, Montana | non-profit organization | World Peace |

|

| Japanese Garden of Peace | Fredericksburg, Texas | National Museum of the Pacific War | A gift from the people of Japan to the people of the United States, presented to honor Chester W. Nimitz and created as a respite from the intensity of violence, destruction, and loss. |

|

| The Peace Dome | Windyville, MO | not-for-profit organization | Many minds working together toward a common ideal to create real and lasting transformation of consciousness on planet Earth. A place for people to come together to learn how to live peaceably.[47] | |

| Shanti Stupa | Pokhara, Nepal | Nipponzan-Myōhōji-Daisanga | One of eighty peace pagodas in the World. |

Theories[편집]

Many different theories of "peace" exist in the world of peace studies, which involves the study of de-escalation, conflict transformation, disarmament, and cessation of violence.[48] The definition of "peace" can vary with religion, culture, or subject of study.

Balance of power[편집]

The classical "realist" position is that the key to promoting order between states, and so of increasing the chances of peace, is the maintenance of a balance of power between states – a situation where no state is so dominant that it can "lay down the law to the rest". Exponents of this view have included Metternich, Bismarck, Hans Morgenthau, and Henry Kissinger. A related approach – more in the tradition of Hugo Grotius than Thomas Hobbes – was articulated by the so-called "English school of international relations theory" such as Martin Wight in his book Power Politics (1946, 1978) and Hedley Bull in The Anarchical Society (1977).

As the maintenance of a balance of power could in some circumstances require a willingness to go to war, some critics saw the idea of a balance of power as promoting war rather than promoting peace. This was a radical critique of those supporters of the Allied and Associated Powers who justified entry into World War I on the grounds that it was necessary to preserve the balance of power in Europe from a German bid for hegemony.

In the second half of the 20th century, and especially during the cold war, a particular form of balance of power – mutual nuclear deterrence – emerged as a widely held doctrine on the key to peace between the great powers. Critics argued that the development of nuclear stockpiles increased the chances of war rather than peace, and that the "nuclear umbrella" made it "safe" for smaller wars (e.g. the Vietnam war and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia to end the Prague Spring), so making such wars more likely.

Free trade, interdependence and globalization[편집]

It was a central tenet of classical liberalism, for example among English liberal thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th century, that free trade promoted peace. For example, the Cambridge economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) said that he was "brought up" on this idea and held it unquestioned until at least the 1920s.[49] During the economic globalization in the decades leading up to World War I, writers such as Norman Angell argued that the growth of economic interdependence between the great powers made war between them futile and therefore unlikely. He made this argument in 1913. A year later Europe's economically interconnected states were embroiled in what would later become known as the First World War.[50]

These ideas have again come to prominence among liberal internationalists during the globalization of the late 20th and early 21st century.[51] These ideas have seen capitalism as consistent with, even conducive to, peace.

Democratic peace theory[편집]

The democratic peace theory posits that democracy causes peace because of the accountability, institutions, values, and norms of democratic countries.[52]

Territorial peace theory[편집]

The territorial peace theory posits that peace causes democracy because territorial wars between neighbor countries lead to authoritarian attitudes and disregard for democratic values.[53][54] This theory is supported by historical studies showing that countries rarely become democratic until after their borders have been settled by territorial peace with neighbor countries.[55][56]

War game[편집]

The Peace and War Game is an approach in game theory to understand the relationship between peace and conflicts.

The iterated game hypotheses was originally used by academic groups and computer simulations to study possible strategies of cooperation and aggression.[57]

As peace makers became richer over time, it became clear that making war had greater costs than initially anticipated. One of the well studied strategies that acquired wealth more rapidly was based on Genghis Khan, i.e. a constant aggressor making war continually to gain resources. This led, in contrast, to the development of what's known as the "provokable nice guy strategy", a peace-maker until attacked, improved upon merely to win by occasional forgiveness even when attacked. By adding the results of all pairwise games for each player, one sees that multiple players gain wealth cooperating with each other while bleeding a constantly aggressive player.[58]

Socialism and managed capitalism[편집]

Socialist, communist, and left-wing liberal writers of the 19th and 20th centuries (e.g., Lenin, J.A. Hobson, John Strachey) argued that capitalism caused war (e.g. through promoting imperial or other economic rivalries that lead to international conflict). This led some to argue that international socialism was the key to peace.

However, in response to such writers in the 1930s who argued that capitalism caused war, the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) argued that managed capitalism could promote peace. This involved international coordination of fiscal/monetary policies, an international monetary system that did not pit the interests of countries against each other, and a high degree of freedom of trade. These ideas underlay Keynes's work during World War II that led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank at Bretton Woods in 1944, and later of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (subsequently the World Trade Organization).[59]

Justice and wholeness[편집]

Borrowing from the teachings of Norwegian theorist Johan Galtung, one of the pioneers of the field of Peace Research, on 'Positive Peace',[60] and on the writings of Maine Quaker Gray Cox, a consortium of theorists, activists, and practitioners in the experimental John Woolman College initiative have arrived at a theory of "active peace". This theory posits in part that peace is part of a triad, which also includes justice and wholeness (or well-being), an interpretation consonant with scriptural scholarly interpretations of the meaning of the early Hebrew word shalom. Furthermore, the consortium have integrated Galtung's teaching of the meanings of the terms peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding, to also fit into a triadic and interdependent formulation or structure. Vermont Quaker John V. Wilmerding posits five stages of growth applicable to individuals, communities, and societies, whereby one transcends first the 'surface' awareness that most people have of these kinds of issues, emerging successively into acquiescence, pacifism, passive resistance, active resistance, and finally into active peace, dedicating themselves to peacemaking, peacekeeping or peace building.[61]

International organization and law[편집]

One of the most influential theories of peace, especially since Woodrow Wilson led the creation of the League of Nations at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, is that peace will be advanced if the intentional anarchy of states is replaced through the growth of international law promoted and enforced through international organizations such as the League of Nations, the United Nations, and other functional international organizations. One of the most important early exponents of this view was Alfred Eckhart Zimmern, for example in his 1936 book The League of Nations and the Rule of Law.[62]

Trans-national solidarity[편집]

Many "idealist" thinkers about international relations – e.g. in the traditions of Kant and Karl Marx – have argued that the key to peace is the growth of some form of solidarity between peoples (or classes of people) spanning the lines of cleavage between nations or states that lead to war.[63]

One version of this is the idea of promoting international understanding between nations through the international mobility of students – an idea most powerfully advanced by Cecil Rhodes in the creation of the Rhodes Scholarships, and his successors such as J. William Fulbright.[64]

Another theory is that peace can be developed among countries on the basis of active management of water resources.[65]

Lyotard post-modernism[편집]

Following Wolfgang Dietrich, Wolfgang Sützl[66] and the Innsbruck School of Peace Studies, some peace thinkers have abandoned any single and all-encompassing definition of peace. Rather, they promote the idea of many peaces. They argue that since no singular, correct definition of peace can exist, peace should be perceived as a plurality. This post-modern understanding of peace(s) was based on the philosophy of Jean Francois Lyotard. It served as a fundament for the more recent concept of trans-rational peace(s) and elicitive conflict transformation.

In 2008, Dietrich enlarged his approach of the many peaces to the so-called five families of peace interpretations: the energetic, moral, modern, post-modern and trans-rational approach.[67] Trans-rationality unites the rational and mechanistic understanding of modern peace in a relational and culture-based manner with spiritual narratives and energetic interpretations.[68] The systemic understanding of trans-rational peaces advocates a client-centred method of conflict transformation, the so-called elicitive approach.[69]

Day[편집]

Peace day was founded as a day to recognize, honour and promote peace. It is commemorated each year by United Nations members.

Studies, rankings, and periods[편집]

Peace and conflict studies[편집]

Peace and conflict studies is an academic field which identifies and analyses violent and nonviolent behaviours, as well as the structural mechanisms attending violent and non-violent social conflicts. This is to better understand the processes leading to a more desirable human condition.[70] One variation, Peace studies (irenology), is an interdisciplinary effort aiming at the prevention, de-escalation, and solution of conflicts. This contrasts with war studies (polemology), directed at the efficient attainment of victory in conflicts. Disciplines involved may include political science, geography, economics, psychology, sociology, international relations, history, anthropology, religious studies, and gender studies, as well as a variety of other disciplines.

Measurement and ranking[편집]

Although peace is widely perceived as something intangible, various organizations have been making efforts to quantify and measure it. The Global Peace Index produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace is a known effort to evaluate peacefulness in countries based on 23 indicators of the absence of violence and absence of the fear of violence.[71]

The last edition of the Index ranks 163 countries on their internal and external levels of peace.[72] According to the 2017 Global Peace Index, Iceland is the most peaceful country in the world while Syria is the least peaceful one.[73] Fragile States Index (formerly known as the Failed States Index) created by the Fund for Peace focuses on risk for instability or violence in 178 nations. This index measures how fragile a state is by 12 indicators and subindicators that evaluate aspects of politics, social economy, and military facets in countries.[74] The 2015 Failed State Index reports that the most fragile nation is South Sudan, and the least fragile one is Finland.[75] University of Maryland publishes the Peace and Conflict Instability Ledger in order to measure peace. It grades 163 countries with 5 indicators, and pays the most attention to risk of political instability or armed conflict over a three-year period. The most recent ledger shows that the most peaceful country is Slovenia on the contrary Afghanistan is the most conflicted nation. Besides indicated above reports from the Institute for Economics and Peace, Fund for Peace, and University of Maryland, other organizations including George Mason University release indexes that rank countries in terms of peacefulness.

긴 요정[편집]

현재 존재하는 국가 중 가장 긴 평화와 중립 기간은 1814년 이후 스웨덴과 1815년 이후 공식적인 중립 정책을 펴온 스위스에서 관찰된다. 이는 유럽과 세계의 상대적인 평화 시기인 팍스 브리태니커(1815-1914), 팍스 유로파이아/팍스 아메리카나(1950년대 이후), 팍스 아토미카(1950년대 이후)에 의해 부분적으로 가능해졌다.

평화의 긴 기간의 다른 예들은 다음과 같다:

- 에도 시대(도쿠가와 막부라고도 함)의 고립 시대(1603년 ~ 1868년)

- 약 700년 ~ 950년 AD(터키 남동부), 카자르 칸국의 팍스 카자르카

- 로마 제국의 팍스 로마나(190년 또는 206년)

또한 볼것[편집]

- Anti-war

- Catholic peace traditions

- Creative Peacebuilding

- Grey-zone (international relations)

- Group on International Perspectives on Governmental Aggression and Peace (GIPGAP)

- Human overpopulation#Warfare and conflict over dwindling resources

- List of peace activists

- List of places named Peace

- List of peace prizes

- Moral syncretism

- Non-violent

- Non-aggression principle

- Peace education

- Peace in Islamic philosophy

- Peace Journalism

- Peace makers

- Peace One Day

- Peace Palace

- Peace symbol

- Perpetual peace

- Prayer for Peace

- Structural violence

- Sulh

- War resister

같이 보기[편집]

- 평화학(평화 연구)

- 분쟁

- 전쟁

- 평화를 원한다면 전쟁에 대비하라(en:Si vis pacem, para bellum)

- 힘을 통한 평화(en:Peace through strength)

- 세계 평화

각주[편집]

- ↑ “UN Logo and Flag”. 《UN.org》. United Nations. 2020년 12월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ “International Day of Peace 2020 Poster” (PDF). 《UN.org》. United Nations. 2020년 12월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ 2007년 대한 성공회 서울교구 주일학교 교사 강습회 교재, '오소서. 오소서. 평화의 왕'

- ↑ Dalai Lama XIV: Quotable Quotes 보관됨 17 9월 2017 - 웨이백 머신 Goodreads. Downloaded 15 September 2017

- ↑ 요한 갈퉁, 강종일 외 역, 평화적 수단에 의한 평화, 들녘, 2000

- ↑ 요한 크리스토프 아놀드, 이진권 역, 《평화주의자 예수》, 샨티, 414년, ISBN 89-91075-32-0

- ↑ 《탐욕의 시대》/장 지글러 지음/양영란 옮김/갈라파고스 펴냄

- ↑ 다만 십계명에서 이르는 살인은 종교적·법률적 일탈행위로서의 살인을 가리키는 것이므로, 군인의 국가 방위로서의 살생은 십계명에서 이르는 살인이 아니라는 견해도 있지만, 이에 대한 반론도 있다. 그 실례로 성공회 신학자 스탠리 하우어워스는 십계명에서 말하는 살인과 구약성서 전체에서 말하는 살인은 총기사용을 정당화하는 사람들의 주장과는 달리, 같은 히브리어 단어를 쓰고 있다고 말한다. 성서에서는 모든 형태의 살인을 금지하고 있다는 것이다. 《십계명》/스탠리 하우어워스, 윌리엄 윌리몬 같이 씀/강봉재 옮김/복있는 사람

- ↑ 박노자,유대인은 십계명을 지켜라!, 한겨레21, 2000.11.30 제335호

- ↑ 《평화주의자 예수》/요한 크리스토프 아놀드 씀/이진권 올김/샨티

- ↑ 그리스도께서는 자신을 희생하여 유다인과 이방인을 하나의 새 민족으로 만들어 평화를 이룩하시고 또 십자가에서 죽으심으로써 둘을 한 몸으로 만드셔서 하느님과 화해시키시고 원수되었던 모든 요소를 없이하셨습니다. 이렇게 그리스도께서는 세상에 오셔서 하느님과 멀리 떨어져 있던 여러분에게나 가까이 있던 유다인들에게나 다 같이 평화의 기쁜 소식을 전해 주셨습니다. 그래서 이방인 여러분과 우리 유다인들은 모두 그리스도로 말미암아 같은 성령을 받아 아버지께로 가까이 나아가게 되었습니다. 에페소인들에게 보낸 편지 2:15-18

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary, "Peace" 보관됨 14 12월 2013 - 웨이백 머신.

- ↑ Benner, Jeff: Ancient Hebrew Research centre: http://www.ancient-hebrew.org/27_peace.html 보관됨 26 4월 2014 - 웨이백 머신

- ↑ “Peace Sign”. 《Inner Peace Zone》 (미국 영어). 2021년 8월 28일. 2021년 12월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ Amelia Dowler, Curator, British Museum; A History of the World; http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/7cEz771FSeOLptGIElaquA

- ↑ Šmihula, Daniel (2013): The Use of Force in International Relations, p. 129, ISBN 978-80-224-1341-1.

- ↑ “Protect Heritage Now for Resilience and Peace”. 2015년 11월 26일.

- ↑ “UNESCO Legal Instruments: Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict 1999”.

- ↑ UNESCO convenes Libyan and international experts meeting for the safeguard of Libya's cultural heritage. UNESCO World Heritage Center - News, 21. Oktober 2011; Roger O’Keefe, Camille Péron, Tofig Musayev, Gianluca Ferrari "Protection of Cultural Property. Military Manual." UNESCO, 2016, p 73; Eric Gibson: The Destruction of Cultural Heritage Should be a War Crime. In: The Wall Street Journal, 2 March 2015; UNESCO Director-General calls for stronger cooperation for heritage protection at the Blue Shield International General Assembly. UNESCO, 13 September 2017.

- ↑ “UNIFIL - Action plan to preserve heritage sites during conflict, 12 Apr 2019.”. 2019년 4월 12일.

- ↑ “Austrian Armed Forces Mission in Lebanon” (독일어).

- ↑ Jyot Hosagrahar: Culture: at the heart of SDGs. UNESCO-Kurier, April-Juni 2017; Rick Szostak: The Causes of Economic Growth: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009, ISBN 9783540922827.

- ↑ “The Role and Responsibilities of the Police” (PDF). Policy Studies Institute. xii쪽. 2009년 12월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lioe, Kim Eduard (2010년 12월 3일). 《Armed Forces in Law Enforcement Operations? – The German and European Perspective》 1989판. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 52–57쪽. ISBN 978-3-642-15433-1.

- ↑ Romm, Joseph J. (1993). 《Defining national security: the nonmilitary aspects》. Pew Project on America's Task in a Changed World (Pew Project Series). Council on Foreign Relations. 122쪽. ISBN 978-0-87609-135-7. 2010년 9월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 Rogers, P (2010). 《Losing control : global security in the twenty-first century》 3판. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745329376. OCLC 658007519.

- ↑ “Excerpt from the Will of Alfred Nobel”. Nobel Foundation. 2007년 10월 26일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2008년 3월 31일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Archived copy” (PDF). 2013년 6월 9일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 6월 9일에 확인함.

- ↑ Cecil Rhodes's goal of Scholarships promoting peace highlighted – The Rhodes Scholarships 보관됨 22 9월 2013 - 웨이백 머신. Various materials on peace by Warden of the Rhodes House Donald Markwell in Markwell, "Instincts to Lead": On Leadership, Peace, and Education. Connor Court, 2013.

- ↑ E.g., Donald Markwell, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ↑ http://www.politics.ox.ac.uk/materials/news/Fulbright_18May12_Arndt.pdf 보관됨 22 9월 2013 - 웨이백 머신, “Archived copy”. 2013년 9월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 9월 26일에 확인함.

- ↑ See, e.g., "The Rhodes Scholarships of China" in Donald Markwell, "Instincts to Lead": On Leadership, Peace, and Education, Connor Court, 2013.

- ↑ Benner, Jeff: Ancient Hebrew Research Center:http://www.ancient-hebrew.org/27_messiah.html 보관됨 26 4월 2014 - 웨이백 머신>

- ↑ "For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, 'Prince of Peace'." [New International Version]

- ↑ Beaman, Jay; Pipkin, Brian K. (2013). 《Pentecostal and Holiness Statements on War and Peace》 (영어). Wipf and Stock Publishers. 98–99쪽. ISBN 9781610979085.

- ↑ “Article 22. Peace, Justice, and Nonresistance” (영어). Mennonite Church USA. 2021년 6월 4일에 확인함.

- ↑ “peaceful quran”. 2016년 5월 9일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ “peaceful quran”. 2016년 5월 9일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 4월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ Isaiah 2:4

- ↑ Isaiah 11:6–9

- ↑ Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism Page 163. 2006. By Bernard McGinn.

- ↑ “For Libertarians, There Is Only One Fundamental Right”. 2015년 3월 29일.

- ↑ “"The Morality of Libertarianism"”. 2015년 10월 1일.

- ↑ “The Non-Aggression Axiom of Libertarianism”. Lew Rockwell. 2016년 3월 22일에 확인함.

- ↑ “""Good ideas don't require force"”. 2021년 7월 4일.

- ↑ R.K. Prabhu & U.R. Rao, editors; from section "The Gospel Of Sarvodaya" 보관됨 27 9월 2011 - 웨이백 머신, of the book The Mind of Mahatma Gandhi 보관됨 20 12월 2010 - 웨이백 머신, Ahemadabad, India, Revised Edition, 1967.

- ↑ “The Peace Dome History”. 《peacedome.org》. 2014년 2월 2일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 1월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ einaudi.cornell.edu 보관됨 22 10월 2007 - 웨이백 머신

- ↑ Quoted from Donald Markwell, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, chapter 2.

- ↑ “NATO Review - the end of the "Great Illusion": Norman Angell and the founding of NATO”. 2019년 1월 14일.

- ↑ For sources, see articles on liberalism and classical liberalism.

- ↑ Hegre, Håvard (2014). “Democracy and armed conflict”. 《Journal of Peace Research》 51 (2): 159–172. doi:10.1177/0022343313512852. S2CID 146428562.

- ↑ Gibler, Douglas M.; Hutchison, Marc L.; Miller, Steven V. (2012). “Individual identity attachments and international conflict: The importance of territorial threat”. 《Comparative Political Studies》 45 (12): 1655–1683. doi:10.1177/0010414012463899. S2CID 154788507.

- ↑ Hutchison, Marc L.; Gibler, Douglas M. (2007). “Political tolerance and territorial threat: A cross-national study”. 《The Journal of Politics》 69 (1): 128–142. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00499.x. S2CID 154653996.

- ↑ Gibler, Douglas M.; Owsiak, Andrew (2017). “Democracy and the Settlement of International Borders, 1919-2001”. 《Journal of Conflict Resolution》 62 (9): 1847–1875. doi:10.1177/0022002717708599. S2CID 158036471.

- ↑ Owsiak, Andrew P.; Vasquez, John A. (2021). “Peaceful dyads: A territorial perspective”. 《International Interactions》 47 (6): 1040–1068. doi:10.1080/03050629.2021.1962859. S2CID 239103213.

- ↑ Shy, O., 1996, Industrial Organization: Theory and Applications, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

- ↑ N.R. Miller, "Nice Strategies Finish First: A Review of The Evolution of Cooperation", Politics and the Life Sciences, Association for Politics and the Life Sciences, 1985.

- ↑ . See Donald Markwell. John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Galtung, J: Peace by peaceful means: peace and conflict, development and civilization, page 32. Sage Publications, 1996.

- ↑ Wilmerding, John. “The Theory of Active Peace”. 20 June 2009에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 7 February 2010에 확인함.

- ↑ Macmillan, 1936.

- ↑ See, e.g., Sir Harry Hinsley. Power and the Pursuit of Peace, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

- ↑ Discussed above. See, e.g., Donald Markwell. "Instincts to Lead": On Leadership, Peace, and Education (2013).

- ↑ “Publications – Strategic Foresight Group, Think Tank, Global Policy, Global affairs research, Water Conflict studies, global policy strategies, strategic policy group, global future studies”. 《strategicforesight.com》. 2016년 11월 1일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 11월 2일에 확인함.

- ↑ Wolfgang Dietrich/Wolfgang Sützl: A Call for Many Peaces; in: Dietrich, Wolfgang, Josefina Echavarría Alvarez, Norbert Koppensteiner eds.: Key Texts of Peace Studies; LIT Münster, Vienna, 2006

- ↑ Wolfgang Dietrich: Interpretations of Peace in History and Culture; Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2012

- ↑ Wolfgang Dietrich, Josefina Echavarría Alvarez, Gustavo Esteva, Daniela Ingruber, Norbert Koppensteiner eds.: The Palgrave International Handbook of Peace Studies. A Cultural Approach; Palgrave MacMillan London, 2011

- ↑ John Paul Lederach: Preparing for Peace; Syracuse University Press, 1996

- ↑ Dugan, 1989: 74

- ↑ “Vision of Humanity”. 《visionofhumanity.org》. 2011년 2월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2013년 12월 15일에 확인함.

- ↑ Jethro Mullen (2015년 6월 25일). “Study: Iceland is the most peaceful nation in the world”. 《CNN.com》. 2015년 8월 7일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2015년 8월 6일에 확인함.

- ↑ “These are the most peaceful countries in the world”. 《World Economic Forum》. 2017년 7월 15일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 7월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Fragile States 2014”. 《foreignpolicy.com》. Foreign Policy. 2017년 3월 17일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 3월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ “South Sudan Tops List of World's Fragile States – Again”. 《VOA》. 2015년 8월 13일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2015년 8월 6일에 확인함.

참고 문헌[편집]

- Sir Norman Angell. The Great Illusion. 1909

- Raymond Aron, Peace and War. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1966

- Hedley Bull. The Anarchical Society. Macmillan, 1977

- Sir Herbert Butterfield. Christianity, Diplomacy and War. 1952

- Martin Ceadel. Pacifism in Britain, 1914–1945: The Defining of a Faith. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980

- Martin Ceadel. Semi-Detached Idealists: The British Peace Movement and International Relations, 1854–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Martin Ceadel. The Origins of War Prevention: The British Peace Movement and International Relations, 1730–1854. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996

- Martin Ceadel. Thinking about Peace and War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987

- Inis L. Claude, Jr. Swords into Ploughshares: The Problems and Progress of International Organization. 1971

- Michael W. Doyle. Ways of War and Peace: Realism, Liberalism, and Socialism. W.W. Norton, 1997

- Sir Harry Hinsley. Power and the Pursuit of Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962

- Andrew Hurrell. On Global Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008

- Immanuel Kant. Perpetual Peace. 1795

- Donald Markwell. John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Donald Markwell. "Instincts to Lead": On Leadership, Peace, and Education. Connor Court, 2013

- Hans Morgenthau. Politics Among Nations. 1948

- Steven Pinker. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Viking, 2011

- Sir Alfred Eckhard Zimmern. The League of Nations and the Rule of Law. Macmillan, 1936

- Kenneth Waltz. Man, the State and War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978

- Michael Walzer. Just and Unjust War. Basic Books, 1977

- J. Whalan. How Peace Operations Work. Oxford University Press, 2013

- Martin Wight. Power Politics. 1946 (2nd edition, 1978)

- Letter from Birmingham Jail by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

- "Pennsylvania, A History of the Commonwealth," esp. pg. 109, edited by Randall M. Miller and William Pencak, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002

- Peaceful Societies, Alternatives to Violence and War Short profiles on 25 peaceful societies.

- The Path to Peace, by Laure Paquette

- Prefaces to Peace: a Symposium [i.e. anthology], Consisting of [works by] Wendell L. Willkie, Herbert Hoover and Hugh Gibson, Henry A. Wallace, [and] Sumner Welles. "Cooperatively published by Simon and Schuster; Doubleday, Doran, and Co.; Reynal & Hitchcock; [and] Columbia University Press", [194-]. xii, 437 p.

외부 링크[편집]

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Lemonade a la Carnegie accessed 16 October 2012

- Research Guide on Peace by the United Nations Library at Geneva

- PeaceWiki

- Peace Monuments Around the World

- (영어) Peace - Curlie

- Working Group on Peace and Development (FriEnt)

- Answers to: "How do we achieve world peace?"

- World Alliance of Religions Peace Summit (WARP Summit)